Being Dead: A Phenomenological Grave-Side Enquiry

ENVS 6149 Amy Lavender Harris

Culture and Environment April 1998

Course Paper

This paper, written for a graduate course titled “Culture and Environment”, represented my first efforts to make use of ideas of phenomenology and the work of Martin Heidegger. I came across Heidegger’s work in a moment of serendipitous discovery. My use of Heidegger made me unpopular in a Faculty as prone as any other to academic cat-fights: having heard of the “Heidegger controversy”(but having read neither Heidegger nor the work critical of him) some faculty members objected to this work on political grounds. Certainly Heidegger is a controversial figure of twentieth century philosophy, but given that his work is the principal fabric used in the continentalist and post-modern

(and post-postmodern) umbrellas, he deserves reading.

Please do not use this paper without permission and attribution. Comments welcomed. Amy Lavender Harris may be contacted at alharris@yorku.ca .

Being Dead: A Phenomenological Grave-side Enquiry

All lost, all lost, the lapse that went before:

So lost till death shut-to the opened door,

So lost from chime to everlasting chime,

So cold and lost for ever evermore.

Christina Rossetti, “Dead Before Death”

And since the man who is not, feels not woe,

(For death exempts him, and wards off the blow,

Which we, the living, only feel and bear,)

What is there left for us in death to fear?

When once that pause of life has come between

‘Tis just the same as we had never been.

Dryden, “Against the Fear of Death”

Death is a recurrent cultural and spiritual preoccupation. Speculation on death saturates language, literature, ritual, and belief, in which death lies layered, like cracked paint on an ancient effigy. Our living affairs are coloured by our visions of death, as an ever-present emblem; a grinning skull; a secretive lamb; an end; a beginning; nothingness.

But can we know death in an authentic manner? How does the fact that we cannot articulate our personal experience of death affect our cultural and philosophical understandings of it? This paper examines death as a socially, spatially, and temporally situated phenomenon, as a cultural, rather than a literal, experience. The basis of this paper is an examination of how human understandings of death are articulated through language. As such, the arguments are based on two premises: (1) that death is fundamentally an unknown, because nobody alive is able to articulate an authentic experience of death; in this, understandings of death are revealed to be profoundly subjective, and constructed; and (2) that this subjectivity and ‘constructedness’ is articulated and mediated through language. There is no “absolute” associated with death; how we conceive of death is a cultural construction, informed by social and spiritual beliefs, and affected by their intersection with time and space.

This paper begins with existentialist theories about death (focusing in particular on Heidegger’s phenomenology of death), and adopts portions of Shibles’ critique of these approaches to death, particularly in relation to the role of language in articulating subjective experience and belief. Language is argued to be inseparable from, and even formative of, our beliefs about death as cultural constructions; language mediates subjective experience, and articulates what we cannot authentically experience. Once a theoretical argument is established, the remainder of this paper presents some recurrent (western) constructions of death; which it is suggested tend to develop around a variety of occasionally contradictory notions of death and the other; death as separation; death as an inevitability; and death as an unknown, and develops an informal “case study” which demonstrates these constructions in cultural practice. A central image of (western) death, the earth grave, is examined as a cultural symbol reflective and informative of the process of constructing “death” through language.

1. Death as a Phenomenological Experience

The first section of this paper focuses on death as a phenomenological experience, relying heavily on

1

Heidegger’s phenomenology of death, as well as on two subsequent works (Leman-Stefanovic and Huertas-Jourda) in the same strain, and finally on a number of critiques. A broader interpretation of the subjective experience of death is presented, incorporating aspects of the experience of the Other, whose experience is ostensibly rejected by the phenomenal focus on individual subjectivity, but is argued to be made possible by a number of tenets, including the awareness of death responsible for Being-toward-death (Heidegger’s primordial orientation-toward-death), as well as

Huertas-Jourda’s Law of Partial Actualization (or the “passage of the ideal into actual presentation” as an embodiment of consciousness). This section forms a background for the second section, which discusses the role of language in

“constructing” death culturally (death brought from the individual to the collective, yet remaining a profoundly personal experience).

(a) Personal, Subjective Experience

(Western) existentialists’ speculations on the nature of death may be traced, at least in the nature of their enquiry, to the Classical Epicurean and Stoic schools of thought. Epicurus argued that “death is nothing to us; for that which is dissolved, is without sensation, and that which lacks sensation is nothing to us” (Russell, 1961: 255).

Epicurus’ disciple, Lucretius, held similar views: most interesting is his contention that sleep and death lie on the same continuum (the difference being that although one survives sleep, one is not thought to survive death because consciousness dies with the physical body). Epictetus (a Stoic) held a number of views which have reappeared in existential philosophy. He argued that if we cannot truly comprehend death, we should not wallow in negative emotion on death: we should expend our intellectual efforts on things with some useful outcome; we should live rationally, and exert choice on the things we are able to alter (Shibles, 1974: 41-44). Marcus Aurelius anticipates existentialism more directly: life is (and can only be made) meaningful by positive and purposeful thought and action; rational enquiry must be based on an acceptance of the laws of nature, including the inevitability of death; further, such enquiry can also only be truly rational if it is based in current, personal, experience. He appears to echo Epicurus in stating that death is neither good nor bad; either we will have no sensation, or will have new sensations unrelated to our previous existence (ibid.: 56-57). What is interesting about these Classical arguments is their focus on authenticity of experience; on self-determination; on choice, and rationality. We cannot truly know what death is, they claim, and therefore we should not focus our apprehension on death: we should contemplate life instead, as something which we can experience and appreciate (that these philosophies were also escapist cannot be denied, but it is their emphasis on the significance of experience which is of value here).

Following centuries of death-doctrine in a number of (primarily Christian) guises, and the post-Renaissance romanticizing of these doctrines, by the late 19 th century the nature of existence and death was taken up again as a series of questions per se , and attempts were made to rationalize enquiries about death, and separate them from religious dogma and the Romantic/ Victorian Muse. Increasing skepticism and cynicism, and an emphasis on science made these sorts of enquiries both possible and necessary: query focused increasingly on what may be proven and known through ‘real’ evidence. Husserl redirected philosophical enquiry toward that which is encountered, and which may be observed and ‘known’ through experience, but it was Martin Heidegger who suggested that death itself may be approached as a phenomenological enquiry, in his Being and Time (1927).

Heidegger’s main premise about existence and death was the idea of “being-toward- death”. In his arguments 1 , Being is associated with anxiety of “being-in-the-world-itself”. Kierkegaard had earlier discussed linkages between anxiety and the concept of Nothing, but it was Heidegger who related Nothing specifically to death.

According to Heidegger, Man (Humanity) is the only being engaged in the quest for the meaning of Being;

Being-toward-death reveals the “authentic temporal roots of man [humanity] as essentially finite” (Leman-Stefanovic,

1987: xii), and thus provides a basis for understanding existence. Similarly, the “ontic moment” (death) is of primary importance for understanding the ontological (existence) in general, because it forms “in advance the pure aspect of succession which serves as the horizon” (ibid.: xvi). In other words, awareness ahead-of-itself changes the very nature of awareness: anticipation of our own death changes not only the nature of that death (the “horizon”), but also the nature of our life.

1 It is almost a pity that Heidegger is the first, and certainly the authoritative, voice on death-as-phenomenological experience; Being and Time is widely criticised for being incomprehensible both in German and in translation, largely because of what are often considered redundant coinages of terminology. Subsequent writings (e.g., Kaufmann, 1959;

Shibles, 1974) tend to mock his style, logical lapses, and ‘borrowings’; relatively few (Leman-Stefanovic, 1987) attempt to develop his rather fascinating ideas into a more lucid phenomenology of death. I have to admit using only secondary sources in my description of Heidegger’s theories; I rationalize this by focusing on the critique of

Heidegger myself, and direct the attention of dissenters to Kaufmann’s excellent explanation (and critique) of the

Heidegger mystique (in Feifel,1959: 51).

2

Heidegger attempts to get around the difficult fact that we cannot experience (or at least not conventionally document the experience of) our own death, by suggesting that “some kind of phenomenological inference or

‘extrapolation’” may provide a “unique and privileged revelation of what it is like to be dead” (ibid.: 3). He responds to Husserl’s phenomenological reliance on the “reduction to significance” by arguing that death is present insofar as it is meaningful . Leman-Stefanovic develops this as “insofar as I am aware that death will necessarily be present for me at some indeterminate time as a factical event ”, death will be meaningful for me (4). Thus, “a phenomenology of death will not seek to uncover what it is like to be dead, or what the singular event of death is like, but, as a description involving a reduction to meaning, it will be intimately related to a “phenomenology of life”, exploring the ways in which death penetrates human understanding as a necessary condition of being-in-the-world” (ibid.: 5). In essence, as

Heidegger said himself, death is, “in the widest sense, a phenomenon of life ... life’s being is also death. Everything that enters into life also begins to die, to go toward its death, and death is at the same time life.” (quoted in ibid.: 5).

Heidegger very directly responds to Epicurus (and other previous ‘existential’ musings on death) by refuting the notion that we cannot be where death is: he considers what follows the ontic event of death (Epicurus’ focus) to be far less relevant than what precedes it.

In order to remain within the realm of the phenomenological, Heidegger notes that we must guard against

“any ontic re-presentation and unauthentic objectification of the factical event of the death of the Other”

(Leman-Stefanovic, 1987: 7). But here is a problem: how do we separate our own Being-toward-death from the death of the Other, when our only experience of death is the death of the Other? This is a question which does not appear to be adequately answered, and remains as a major criticism of Heidegger, because it is a serious threat to his phenomenological approach. Although it is suggested that we examine death as “that most unsurpassable, non-relational and the most personal of life’s potentialities” (ibid.: 7), neither Heidegger nor subsequent writers in this vein adequately address how we can truly avoid focusing on the Other’s death, when it is this focus which may define our own Being-toward-death.

Instead, writers in the Heideggerean tradition attempt to show how awareness of death, as a “limit”, affects

Being (-in-the-world-itself). Heidegger had suggested that the phenomenon of “care” (loosely, in this context, the sense that there is always something more to accomplish), confronted with the future certainty of death, recognises death as a limit, and deeply and profoundly affects the nature of that existence: death becomes existence, or existence becomes Being-toward-death. He links Being-toward-death to a triad of individuation, transcendence, and temporality; Leman-Stefanovic suggests that transcendence is the key to understanding this set of linkages.

Transcendence, in this context, is related to a “primordial” act of orientation (toward-death); this transcendent process of orientation (toward death) is the condition of experiencing death:

Indeed, according to its essence, the Nothing [death] appears as pure horizon of all objectification, as the ontological condition of the possibility of an encounter thing “things”. Projecting itself in-the-world, in anticipation of a future of possibilities, the transcendence of the human understanding opens up a world within which particular essents are encountered. Thus “ontological knowledge ‘forms’ transcendence and this formation is nothing other than the holding open of the horizon within which the Being of the essent is perceptible in advance” .... It is the transcendental imagination which is the root of transcendence, and the transcendental condition of an encounter with a world which is in fact never fully revealed to understanding. (Leman-Stefanovic, 1987:

21-22).

In his effort to bring a phenomenology of death squarely into its roots in Husserl’s phenomenology, and to build on Heidegger’s transcendent orientation toward death, Huertas-Jourda (1978) considers consciousness. He notes that from a “living now”, a “stream” of lived mental experiences continuously originates; from this, “emergent acts of signification” raise the experience from “primal receptivity” to the epistemic level (119). While this process stresses the “here and now” of experience, it also allows for an abstraction from that experience. On a basic level, not only our lived experiences, but our interpretation and reflection on those experiences, inform our existence. Huertas-Jourda revisits the concept of a “concrete subjectivity”, and suggests that consciousness is made up of both the “real” (as ontologically experienced) and the “ideal”, as the “‘haunting’ aspect lived as ‘represented’ by the real but as not being really there” (123); neither has precedence over the other in constructing awareness (although only one may be realised at any one time). Huertas-Jourda calls this the Law of Partial Actualization, or the “passage of the ideal into actual presentation” as an embodiment of consciousness (123). He considers death in terms of its challenge to consciousness; where the “ideal”, or the actually possible, prevents “fulfilment” of the realisation of consciousness, because “consciousness harbors and is contemporaneous with its wholly opposite which announces itself at best as an obstacle, at worst as a mortal threat.” (126). His conclusion is that the price paid by consciousness for “concrete

3

appearance” is the “constitution of its opposite” as its principal object (127). In other words, in being conscious of our

“actually real” existence, we must accept the awareness of our own “actually possible” death.

(b) The Phenomenology of the Other

While Heidegger’s phenomenological discourse on death (and the analyses posed by Leman-Stefanovic and

Huertas-Jourda) goes much further, particularly with respect to Being-toward-death, transcendence, temporality,

“care”, and a critique of Kant, I would like to focus on specifically on the individual experience-of-death as an ontological reality, and on the apparent contradiction in Heideggerean phenomenology of death, of the difference between the death of the Other and the death of the self. The interpretation seems to imply that the Other is irrelevant to the analysis, because to focus on the Other is to fall into the trap of inauthenticity and re-presentation (see above).

Heidegger focuses on perception in-advance, and on a primordial process of orientation toward death, and attributes this process to the phenomenon of “care”. While I do not wish to deny the argument that these concepts play a significant (and even the major) role in a phenomenological experience of death, I do wish to revisit the importance of the death of the Other in creating this consciousness. The role of the Other in creating a consciousness of death has been taken up, in various forms, by Kaufmann (1959); Mora (1965); Shibles (1974); Bowker (1991), and others.

While strict Heideggerean phenomenologists tend to discount the role of the Other, those who focus on the Other first tend to have greater success in integrating the Other with a phenomenology of death.

Although perhaps a deviation from the direct phenomenology of personal lived experience, it is also clear that our experiences, and our reflections on our experiences, affect the experiences of others (and vice versa). The awareness of death responsible for Being-toward-death (Heidegger’s primordial orientation-toward-death), as well as

Huertas-Jourda’s Law of Partial Actualization (or the “passage of the ideal into actual presentation” as an embodiment of consciousness) is based on some actual experience, of death, in the present case. Yet, Heidegger and his successors allocate text and terminology to an admission that we cannot actually experience death, yet we are able to authentically experience Being-toward-death. This would seem at odds with the principle of subjectivity in phenomenology, because our experience as Beings-toward-death cannot be based on our own experience of death. Even

Huertas-Jourda’s concept of the “actually possible” (or ideal)’s passage into the realm of the actual does not adequately address the source of this transformation. If the source of the possible (or the Being-toward) is not our own experience, it must be the experience of another. Therefore, either death cannot be experienced phenomenologically, or the phenomenology of death must, by definition (or, rather, by volume of words) incorporate the experiences of others.

In presenting what is in many ways the same conclusion, Mora asks: “must we then resign ourselves to saying nothing about death because it is either absolutely one’s own or absolutely another’s? Is there no possibility of integrating these contrasting views so as to give each one its due?” (1965: 177). The solution posed by Mora and others (e.g., Kaufmann (1959); Shibles (1974); Bowker (1991)) incorporates the experiences of others by changing the ground on which the phenomenological argument is based: the issue of the nature of death itself. Two approaches are used; the first is that death is not simply as the “loss of consciousness” normally referred to in the phenomenological literature; “death” incorporates the whole range of experiences, including the observation of the death of others, as an ontic reality (this view, as a teaching proposition influencing Being-toward-death, is of great potential importance in re-evaluating the phenomenology of death. The second (chosen by Shibles; see section 3 below) implies the first, but reaffirms the Classical notion that where death exists, Being doesn’t (and therefore emphasis should be placed on what we can authentically experience). Both point essentially in the same direction, which is of interest in the third section of this paper: “learning” and constructing death culturally, through the appropriation and acceptance of the experience of others (and Others) as our own, in addition to our own “authentic” experiences.

So what of the experience of the other? How can a phenomenology of death, focusing on subjective, authentic, experience, be based on the experiences of others? Mora notes that “if death were, as Sartre puts it, a “pure event” ... then it could not be experienced in any manner whatsoever, except perhaps as the absurd par excellence ”

(177). Mora cites Gabriel Marcel’s contention that the deaths of others are not merely external events; the deaths of others affect those who know them, and Mora extends this to humanity in general, going so far as to contend that the presence of the other is a quality that belongs not only to the other, but also to the self, in a metaphysical sense

(177-178). This latter point is difficult to substantiate, but the notion of somehow authentically experiencing the death of another, in a very real sense, is not so difficult to swallow. Experiencing the death of another (or the Other) is not necessarily tied to experiencing the other’s consciousness (or post-consciousness) after death, but is based rather on experiencing the loss of the other; and of internalizing the knowledge that a similar fate awaits one. In this sense, death becomes a broad range of possible experiences; in order to experience death, we need not all experience the same death in the same way; indeed, this would conflict with the thesis of the subjectivity of individual experience, and

4

would contradict any phenomenological theory of death. Death includes both that which dies, and that which is left behind, and also that which is aware of its own future death. This integrates Heidegger’s phenomenological approach

(Being-toward-death); incorporates authentic and subjective experience (and Huertas-Jourda’s passage of the ideal into actual presentation), and also admits the experiences of the Other as influencing our own experiences.

If death is accepted as a range of possible experiences, then multiple perspectives must be taken into consideration. Since we as living individuals cannot authentically experience our own death (as an ontic moment), and cannot share the ontic experience of the death of the Other, we must base our understanding of death on some collection of the experiences of the Other, of our speculations on the experiences of others in death, of our awareness of our own mortality, and perhaps of our experiences as dying (but conscious and articulate) individuals, not merely as some sort of root metaphor or expression of a collective unconsciousness, but as real, lived, experiences. Our experience of death (as a range of possible experiences) is constructed from this range of possible experiences. In this way, we can incorporate the experiences of the Other into our own authentic experience of death; we need not exclude them from a phenomenological analysis.

The following section builds on the above, and describes language as a mode of examining the “range of possible experiences” of death. Shibles’ critique of Heidegger is developed in the context of an evaluation of the role of language in articulating our experiences of death. Language is shown to be not merely an important part of articulating the “authentic” experience of death, but also as of profound importance of constructing death as a cultural, as well as an individual, experience.

2. Language and Death as a Subjective Construct

Shibles (1974) identifies what he considers a contradiction in existentialist theory: that consciousness, or being, is assumed and used as a starting point in philosophy. The question of “being” (or “existence”) is an inadequate base, because it is invariably answered with a circular syllogism (“being exists”). Shibles argues that language is a better starting point:

We can hardly see or think of anything without language. Language seems, to a great extent, to constitute and mold reality. It does not just stand for or represent “ideas” and “objects”. To get outside of language is like getting outside of one’s skin. There are not, then, simply objects or entities existing entirely outside of language. To think there are would be to know how one would think without language, without ever having learned a language, or to know how insects think and what they perceive. We see in terms of our language and thought. ... Reality seems to be inextricably bound up with language. Thus there is no ontology separate from language. (83-84)

The potential contradictions of Shibles’ argument notwithstanding (how to effectively separate “language” from the question of “being”, for example), his point about language is an important one. “Reality” is inextricably bound up with language because language articulates the subjectiveness of our experience.

Focusing on the concept of death, Shibles argues that in attempting to define death as an opposite of existence or being (nothingness, non-being), writers fall into the same trap of inadequacy that they do in attempting to define being itself. He points out that death (absolute nothing or absolute nothingness) is outside our experience: “‘nothing’ can be a naming-fallacy if we use it in a contextless or absolute way” (85). He asks “what is meaning”, and goes on:

“do words just somehow stand for, contain, or represent so-called “meanings”?” (89). Using Tolstoy’s story The

Death of Ivan Ilych as an analogy, Shibles presents aspects of death which reveal its undefinable (and subjective) qualities; these may be summarized as follows. First, we are never able to articulate our own death, because “death” really only happens, ontologically speaking, to “others”. Second, we are not given access to the other’s experience of death: we can only speculate on their experience. Associated with this, presumably, is a recognition that if death has meaning for others only (and not for “oneself”), then death may have different meanings, depending on one’s perspective. Third, given our habitual dishonesty about death (including our failure to recognise its formlessness), we render ourselves unable to approach it even as a construction. Fourth, because we do not know when death will occur, we cannot truly anticipate it (Shibles relates this to his conception of time as change and not as a thing in itself; we cannot anticipate nothing): “death cannot be experienced anyway, only dying can” (101). Fifth, one cannot truly imagine one’s own death: “when faced with death we create myths, fictions, religions, rationalizations, and are often more dishonest than ever” (109). Sixth, although we imagine death as one bookend to life (opposite birth, presumably), this wholeness is only a myth, because death cannot effectively be a limit to those who live. Finally, our

5

attempts to re-evaluate our lives in the knowledge of death are flawed in that they cannot be related to death, and offer no understanding of it (there is no “authentic” confrontation between life and death). Shibles’ statements (including 7 others which are each some variation on the above) underscore his point that defining “death” ontologically, particularly as a counterpoint to existence or being, is a circular and illegitimate project. We can neither experience nor define death as a single ontic event; we can only speculate on its meaning, and this is a profoundly subjective effort.

In answer to what he considers the impossibility/ illegitimacy of adequately defining death (in a philosophical/ existential context), Shibles suggests that “‘I don’t know,’ is a statement which can often have a great deal of support and be an elevating statement as well.” (88). Beginning with a recognition of our ignorance allows us to admit that we construct death: “by being conscious and choosing certain concepts to explain with, we create our own notion of what death is - and that notion is nothing more than our own creation.” (94). Accepting that we can neither authentically experience nor define death does not mean that we should not give up on the project, nor that the recurrent efforts to do so should be renounced. Rather, it enables us to open our minds to a recognition of the cultural subjectivity of the concept of death: we should analyse how we think about death, not death itself.

... what is mainly needed is a clear analysis of how death plays a part in our thought. Such analysis,

I would suggest, may be gained by a careful critical examination of the way death and death concepts are used and conceived of in our language. .... Our language, including our language about death, is intersubjective, not private, and so my death is not my death as a private experience. ... By means of an intersubjective language we learn to speak and theorize about death.

The important thing about death, or any other experience, is the ability to articulate it. If we cannot articulate our experience of something, we cannot authenticate the existence (or more particularly the nature) of that experience.

Yet, when we attempt to articulate that experience, we cannot help but be subjective: the experience is invariably filtered through our perspective as well as through the perspectives of those we relate it to. In this way, we cannot truly relate even an authentic experience. And death, which cannot be authentically experienced as a single event, but rather is constructed as a “range of experiences”, is even more strongly affected by the medium of language.

So whither death? Does it fade beneath a texture of words? Does the acceptance of its constructed nature render it meaningless? Is there nothing shared about death; are we all alone in our imaginings? In Death, Ritual and

Belief, Douglas Davies seems to echo Shibles in stating that quite to the contrary, language gives power and a sense of social cohesion to beliefs about death: “it is precisely because language is the very medium through which human beings obtain their sense of self-consciousness that it can serve so well as the basis of reaction to the awareness of death.” (1997: 1). Davies produces a set of propositions which underscore his point:

(1) humans are self-conscious; (2) language is the key medium of self-consciousness; (3) death is perceived as a challenge to self-consciousness; (4) language is used as the crucial response to this challenge; (5) funerary rites frame this verbal response, relating it to other behavioural features of music, movement, place, myth, and history; (6) having encountered and survived bereavement through funerary rites and associated behaviour, human beings are transformed in ways which makes them better adapted for their own and for their society’s survival in the world.

What is most interesting about Davies’ argument is his point that language is not only central to our understandings of death, but that it is also essential to rebut the “challenge to self-consciousness”. By theorizing about death; by constructing this unknown, we gain power over it, merely by virtue of the conscious use of language. Language is evidence of our consciousness; through the use of language, we know we are not dead (somewhat reminiscent of the

Epicurean claim that where we are, death is not, and where death is, we are not). Whether one accepts Davies’ optimistic viewpoint that the use of language creates power over death, his argument is a compelling one because of its consideration of the role of language in constructing death culturally.

The remainder of this paper builds on the first two sections, and examines the grave as a cultural symbol, reflective and informative of the experience of death. By example, the experience of the Other is shown to be not only informative of our individual experience of death, but essential to its authenticity. As a cultural symbol constructed through language and representation, the grave is an important emblem of the ontological, authentic, experience of death, both as an individual and subjective occurrence, and as a culturally shared experience.

3. “Laid to Rest”: Constructing the Earth Grave as a Cultural Symbol

6

On some fond breast the parting soul relies,

Some pious drops the closing eye requires;

Even from the tomb the voice of Nature cries,

Even in our ashes live their wonted fires.

Thomas Gray, “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard”

Remember, Friend, as you pass by,

As you are now, so once was I.

As I am now, soon you shall be

Prepare for Death, and follow me.

(common epitaph, pre-1900)

The earth grave is perhaps the most recognisable symbol of western culture. Graves are far more than midden-holes, into which the offal of human refuse is tossed. Burial is far more than disposal; it is a complex, layered, representation of death. This section examines the grave as a site of representation; as a space where individual and cultural understandings of death are constructed. At the grave, a phenomenology of death may be shown to embrace both the experiences of the Other and the Self, which are combined, representationally and literally, into an authentic

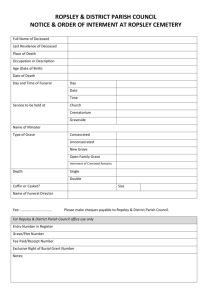

“range of experiences”. It has been shown in the above two sections that death need not be considered as a single ontic moment (“I die”); rather, death becomes a “range of experiences”, experienced subjectively in a variety of manners, all authentic in themselves. Shibles (not entirely dissimilar to Leman-Stefanovic’s assertion that death is authentically present wherever it has meaning) shows that these authentic experiences of death are validated through articulation in language (which, for the sake of this section, may be defined loosely as the range of articulate behaviours, including ritual, metaphor, and explanation). Following a brief introduction to the concept of the grave, four “instances” are considered, as salient indicators of the subjective experience of death: (1) death and the Other; (2) death as separation;

(3) death as inevitability; and (4) death as an unknown. While an infinite range of alternative collections, or

“moments” might be chosen to articulate the authentic nature of the experience of death, these instances may be fairly directly related to the treatment of the phenomenology of death in sections 1 and 2 above.

(a) The Grave: a Brief Depiction

A great deal has been written on cemeteries, and on death, but relatively little on the intersection of the event and space of death. In a metaphorical sense, a cemetery may be seen as a collection of a series of individual experiences of death, each focused on a single grave, massed together to form a collective image or representation.

Henri Lefebvre writes that in the social production of space, “death must be both represented and rejected”, and goes on to claim that although death has a location, it is relegated to the “infinite realm”, because social space remains the space of society and social life: “in absolute space the absolute has no place, for otherwise it would be a non-place

(1991: 35). In section 2 above, Shibles rejects death as an absolute and describes how language brings death into the realm of the socially lived. In this way, spaces of death also exist as social spaces in a direct and representational manner.

It is believed that humans developed rituals of burial early in the pre-history of our present genetic form; archaeologists have discovered a number of sites where bodies were clearly deliberately deposited with care and offerings (ranging from the practical, such as tools, to the symbolic, such as flowers). Burial is not the only means of disposal available to us (virtually every possible method of disposing of a body has been accepted and ritualized at some time or other, including cremation, eating, exposure to animals or the elements, etc.), but burial has been an extremely popular method of disposal, particularly in western societies, and a variety of rationalizations have developed to encourage this behaviour. These include fear of the body itself (or its spirit); fear of disease; aesthetic considerations (decomposition; preventing mauling by animals); a desire to keep kin “together”; symbolic return to the earth; and numerous other reasons (Jones, 1967; Puckle, 1968; Quigley, 1996). Typically, the space of burial is an important sacred space, whether used solely for burial or adapted to other purposes as well (Ariès, 1981; Davies,

1997). In Medieval Europe and antebellum North America, burial within the physical structure of a church was common practice; the churchyard was considered an extension of the interior consecrated space. Strict norms, which evolve across time and place, have conventionally governed burial, including grave orientation, size, and depth, grave markers (the habit of erecting monuments first became popular in Europe during the Middle Ages), single or common graves.

Burial is conventionally the final stage of a funeral ritual (although the body may occasionally be ritually exhumed and the bones stored elsewhere). The body, having been cleansed (often embalmed), dressed, ornamented,

7

and wept and prayed over, is placed in the ground, conventionally in a casket, in a pre-prepared grave often already lined with a vault. Following a formal committal (often recognising the symbolic return to the earth with “ashes to ashes, dust to dust”), the grave is filled. Ultimately a permanent marker is generally installed (now, particularly in

North America, subject increasingly to the dictates of cemetery landscaping and maintenance regulations). Flowers, toys, and other artifacts may be left to mark important events, such as death anniversaries, birthdays, etc.. Those who knew the dead may return often or infrequently, to visit, mourn, or to contemplate their own mortality.

It is clear from the above description that graves are important physical and symbolic spaces of death. With the variety of behaviours and roles created in the process/ ritual of burial, and the series of beliefs and feelings these behaviours and roles engender, a grave becomes a setting for examining how death is constructed as an authentic experience. The following four “instances” of the experience of death elaborate on this, and show something of the subjective meaning of death.

(b) “Instances” of the Authentic Experience of Death

(i) The Other

Earlier in this paper, the phenomenological reliance on authentic experience was broadened to include the

Other. Phenomenological theory has responded to our inability to authentically experience death as an ontic event by suggesting that humans exist as Beings-toward -death; that the actually possible is transmuted into the actually real by a primordial orientation-toward death; and that the ontic moment of death exists for us so long as it has meaning for us.

It is claimed in this paper that such manipulation focuses unnecessarily on the experience of death itself, which nobody can truly experience but the dead. Death itself may become an authentic experience for us if two aspects of the phenomenological argument (as it pertains to death) are amended: first, that death consists actually of a series of events, not a single condition; and secondly, that death consists of a range of possible subjective experiences. The role of the Other in exposing us to the experience of death, and in helping coordinate this experience, may be demonstrated using the grave as a setting.

It is rather narrow to limit “death” to the condition of being dead. Since the living are unable to experience this condition, and the dead are unable to articulate their experience, considering death solely in this manner makes any sort of enquiry impossible. At the same time, it makes little sense to limit a discussion of our experiences of death purely to our own condition as living beings (or Beings-toward-death, in Heidegger’s words). Nonetheless, as living humans, we develop an authentic understanding of death, which, I would argue, is based on an authentic experience of death, which comes from experiencing the death of others. We cannot innately “know” death; we can only come to an awareness of death by knowing that others die. This awareness is mediated through rituals associated with death and burial, which are, in large part, teaching devices to help us deal with this new and unwelcome knowledge.

Closely related to the concept of “learning” death from participating in another’s experience of death is the fact that when somebody dies, we also experience their death in a very real way. We may feel loss if the person was close to us; certainly, we are very aware that they are no longer “with us” in any active sense (death being defined, perhaps, as complete and permanent unresponsiveness). Indeed, Mora (1965) considers the general shared nature of being human sufficient basis for the common experience of death; we experience their loss, therefore we have experienced their death. We actively participate in the experience of death by feeling emotion; by participating in rituals of death; by continuing to exist in the same manner as before, while the deceased no longer do. It is a truism that the rituals of death exist for the living rather than for the dead. From our perspective, we “experience” death more so than does the dead person; the dead are described variously as sleeping or lying senseless (the perceived inability of the dead to feel physical pain or emotional loss is customarily cited). When another dies, their earthly responsibilities have ended. It remains for the living to care for the corpse; to arrange for its appropriate disposal; to ensure that the dead person is properly commemorated; to care for ourselves as grieving individuals.

(ii) Separation

Throughout this paper, “the Other” has referred to another person’s experience of death, which informs (and plays a major role in constructing) our own experience of death. It should be noted, however, that part of our lived experience of (another’s) death is the transformation of “another” into the Other. In the literature, the Other tends to refer to an other who is opposed to the Self through some process of alienation, polarization, or separation. Since in dying, other people pass into a state in which they are no longer responsive to us, nor to any other environmental stimuli which previously elicited a response, they become in all ways alienated from our living state. Our experience of death consists first of learning of death from “others”; and secondly, of transforming those “others” into Others.

8

Simply put, in our experience of death, those who become dead ultimately lose their distinguishing character traits and become similar: they are the Dead; Ghosts; Ancestors. We stop thinking of these others in terms of their active relationships with ourselves; they become “past entities”. To illustrate, belief in life after death, in some other-worldly or heavenly realm, is a symbol of the transformation of the dead into Others. In this post-life existence, the dead are believed to have experiences which are related or connect in no way to their previous experiences; customarily, there is no connection between these two worlds. Significantly, we tend to represent these other worlds as either infinitely lovely or unbearably terrible.

The transformation of the dead into Others is represented in the act of burial. Religious burial services incorporate a formal statement consigning the body to the earth and the soul to its destination (which it has already reached, presumably). Through the act of burial, we sever our connection with the deceased as an individual. We separate them physically with earth and a stone (previous superstitions have held that the stone - sometimes called a

“breast stone” - was placed to keep the dead from rising and wandering among the living). Davies (1997) suggests that the act of burial is an illustration of what anthropologists term “rites of passage”: we hold these “rites” to conduct the transition of the person from one status to another; in this case, from existence as an individual to that of an Other. Our view of the dead Other may be shown by our treatment of the long-dead. After time has passed, we lose much of what remains of our ties to the dead, since they no longer share our daily experiences. Old bones may be unearthed and placed elsewhere, even mixed together, for practical or other purposes (in some areas of Greece, graves are dug up after a year and the bones ceremonially washed and placed in a family crypt; the grave is then reused). The person who gave the bones life has gone; the bones have less significance to us now.

Just because someone/something has become an Other doesn’t mean they no longer exist; in the case of dead

Others, it provides us with the opportunity to mould them, in a more formalized way, into our own image of them. We construct graves as monuments to the lives of those who have died. Pertinent personal information (names, ages, dates of birth and death) is a statement that the person is gone; were they alive, we would not require these personal reminders of such basic information. Epitaphs carved on tomb-stones tend to celebrate the life of the grave’s occupant: they are a re-representation of the best traits of the individual. The dead cannot speak for themselves; now, their name is all we have left of them. Related to the erection of monuments and the creation of sometimes elaborate inscriptions and memorial statements is our commemoration of our past relationship with the dead by visiting them. We recognise the grave as the last place we (conventionally) encounter the dead, and we return to this site in an effort to recapture this relationship. Grave visits tend to conflict with customary religious belief which hold that the soul of the deceased has departed to other realms; the compulsion to return to the scene remains nonetheless.

(iii) Inevitability

Earlier societies managed so that memory, the substitute for life, was eternal and that at least the thing which spoke death should itself be immortal: this was the monument. ... But History is a memory fabricated according to positive formulas, a pure intellectual discourse which abolishes mythic Time ... once I am gone, no one will any longer be able to testify to this: nothing will remain but an indifferent nature. (Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida )

Heidegger, Leman-Stefanovic, and Huertas-Jourda focus a major part of their effort in showing how our

Being-toward-death is centred on a primordial “orientation toward death”. Our authentic experience of death is predicated on arriving at a realization of the inevitability of our own death. The above writers attribute this realization to a transcendental process, in which the experience of death “is perceptible in advance”. The above-noted “instances” of experiencing the death of the Other and separation from the Other explain the source of this “transcendental” process, but a major part of the nature of this experience is the realisation of the inevitability of our own death. As shown above, not only do we learn how to experience death from the Other: we also learn about the inevitability of death from the Other.

Graves are places of remembrance, and of instruction. Each grave is a reminder that we too will die; as the common early American epitaph reads: “As I am now, soon you shall be; Prepare for Death, and follow me”. Shibles suggests that we cannot authentically know that we will die, but an important part of our experience of death is an awareness of our own future death. Certainly, there is little evidence to the contrary. We are surrounded by the graves of those who have died before us; the ground is saturated with bodies. Plots may be purchased for families, with a spot reserved for each; while visiting dead family members, one may also inspect one’s own future grave. The current trend toward “pre-planning” for death is a very real representation of the inevitability of one’s own death. We are encouraged to invest in our own death; death becomes a real estate transaction. Once we have designated the physical space of our own grave, how can we then deny our own future death? Death exists for us, even while we live; the grave

9

is waiting for us, biding time, much as we do between eternities.

(iv) Unknown

Of all the things a grave represents and informs our experience of death, the unknown nature of death is probably the most significant impression we are left with. One of the reasons death is such a constant curiosity is because it is profoundly unknown to us: this is what has fuelled millennia of speculation on what follows death, and on defining what “death” is, as a condition and an experience. It is true that the dead tell us no secrets; they lie inert, ultimately mocking us with their grinning vacancy, the earth having carried their secrets away with their flesh and spirit. Heidegger, like many before and after him, describes death as Nothing; perhaps what he is attempting to get at is this Unknown. We experience death as a question: when we consider our own inevitable mortality, or when we contemplate the death of another, our efforts are spent in attempting to understand why death occurs; what it means; how it happens. We don’t understand, but instead use the grave as a touchstone, for wondering.

The grave represents our attempt to understand this “unknown” of death. We construct the grave as a black box, through which we attempt to peer into the recesses of death. By ritually interring our dead; by engaging in elaborate rituals; by attempting to codify death through intellectual and medical descriptions, we attempt to impose order on death. By the time a body reaches the grave, often it has been probed already for specific and genetic causes of its mortality; in the instances when such causes are found, often the body never reaches the grave; instead, it is preserved in solution for future reference. To resign a body to the earth, we first accept our ignorance about its present condition.

An interesting preoccupation which illustrates the “unknown” of death is our concern with what constitutes death, biologically. This is of great concern to us, because the greatest horror is to be considered dead while still alive.

In the past, some members of society kept corpses unburied until they began to decay (also a way to protect the corpse from body-snatchers); given the difficulty of determining whether death has occurred, decomposition is the only certain means of being certain. Jones (1967) and Puckle (1968) describe some of the lengths people have gone to in order to prevent being buried alive; these efforts include mechanical devices to alert grave-side mourners that one is alive; and even, occasionally, a means of causing one’s own death if there is no way to get out.

4. Conclusion

This paper has examined death as a phenomenological experience. Martin Heidegger’s conceptions of

Being-toward-death is examined, and broadened to incorporate a wider definition of death as a range of experiences and events, rather than a single ontic moment; and to accept the influences of others (Others) on our own experiences, while retaining a phenomenological approach. The constructed nature of our experience of death is examined with reference to the grave as a cultural symbol, representative of the death as an individual and collective experience. As a site of representation of these experiences, the grave highlights several aspects, namely the role of the experience of

Others; the process of separation; the acceptance of the inevitability of death; and our voyages into death as an unknown.

SOURCES

Ariès, Philippe, 1981. The Hour of Our Death.

New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Barthes, Roland, 1997 (1981). Camera Lucida. In Spiegel, Maura and Richard Tristman, 1997.

The Grim Reader: Writings on Death, Dying, and Living On.

New York: Anchor/ Doubleday.

Bowker, John, 1991. The Meanings of Death.

Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Davies, Douglas J., 1997. Death, Ritual and Belief: The Rhetoric of Funeral Rites.

London and Washington: Cassell.

10

Huertas-Jourda, José, 1978. Is a Husserlian Phenomenology of Death Possible? In Hetzler,

Florence M, and Austin H. Kutscher, 1978. Philosophical Aspects of Thanatology.

New York: MSS Information Corporation/ Arno Press.

Jones, Barbara, 1967. Design for Death.

London: Andre Deutsch.

Kaufmann, Walter, 1959. Existentialism and Death. In Feifel, Herman, ed., 1959. The Meaning of

Death. New York, Toronto: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Lefebvre, Henri, 1991. The Social Production of Space.

Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Leman-Stefanovic, Ingrid, 1987. The Event of Death: A Phenomenological Enquiry.

Dordrecht, Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Mora, José Ferrater, 1965. Being and Death: An Outline of Integrationist Philosophy.

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press.

Puckle, Bertram S., 1968. Funeral Customs: Their Origin and Development.

Detroit, Michigan: Singing Tree Press (originally published in 1926 by London: T. Werner Laurie Ltd.

Quigley, Christine, 1996. The Corpse: A History.

Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Russell, Bertrand, 1961. History of Western Philosophy; and its Connection with Political and

Social Circumstances from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. 2 nd ed.

London: Routledge.

Shibles, Warren, 1974. Death: An Interdisciplinary Analysis.

Whitewater, Wisc.: The Language Press. xvii