alimoertopo - Anthropological Society of Western Australia

advertisement

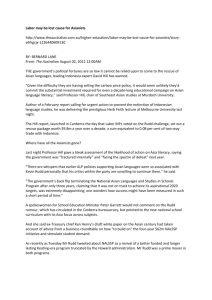

page 1 The Evolutionist Anthropology of Ali Moertopo: Agency and Coercion in Developing a Pancasila Society in Indonesia1 Greg Acciaioli Nations, however, have no clearly identifiable births, and their deaths, if they ever happen, are never natural. Because there is no Originator, the nation's biography can not be written evangelically, ‘down time,’ through a long procreative chain of begettings. The only alternative is to fashion it ‘up time’" – towards Peking Man, Java Man, King Arthur, wherever the lamp of archaeology casts its fitful gleam (Anderson 1991: 205) Introduction: Anthropological Implications of the `Antiquity' of the Nation In his classic treatment of the origins of nationalism, Benedict Anderson (1991) focuses on the change of consciousness expressed by adherence to this notion. Nationalism is a radical reconceptualisation of modes of togetherness, the postulation of an `imagined political community--...imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign' (Anderson 1991: 6). Part of the concept's radicalness is the very paradoxes that it encompasses, including contradictions between: firstly, the objective modernity of the newly emerging nations whose members espouse it and their subjective antiquity; secondly, the universality of its occurrence as a concept and the unique content of its formulation in each case; and, thirdly, its political power as an ideology and its philosophical poverty (Anderson 1991: 5). This new consciousness, in his view, requires the creation of an altered sense of memory and a new framework of time within which to remember. Borrowing from Walter Benjamin, Anderson contrasts Messianic time--`a simultaneity of past and future in an instantaneous present'--with its replacement by `homogenous, empty time', in which simultaneity is transverse, cross-time. In this new temporal framework simultaneity is not given by the religious framing of prefiguration and fulfilment, but rather by temporal conincdence, as measured by clock and calendar (Anderson 1991: 24). The nation can then be seen as an entity moving calendrically through this time, `moving steadily down (or up) history' (Anderson 1991:26). In the revised edition of Imagined Communities Anderson's framework emphasises the role of several institutions of power in the colonial state that could be harnessed by newly emerging national movements to effect this shift of consciousness, especially the circumscribing and `logoising' potency of the census's abstract quantification/serialisation of persons, the map's inscription of political space, and the museum's genealogising of cultural history (Anderson 1991: xiv, 163186). He still maintains the centrality of the technology of print capitalism in enabling this shift of consciousness, especially the power of the newspaper and the Prepared for the Anthropological Society of Western Australia Symposium, ‘Ancestors and Contemporaries: Engaging Anthropological Practice in and beyond the Academy’. 1 October 2010. Draft Only – Not for quotation without the author's permission, but comments are welcome. 1 page 2 novel to unite a readership into a nationality, but the new final chapter also emphasises the importance of the writing of history to encode this vision of a shared nation. For it is in its history that the members of a nation come to forge their identity. The French nation brought into birth by the revolution is, quite literally, inconceivable without the history that Michelet wrote for it. But in this regard perhaps Anderson has not gone far enough. Although himself emphasising the `antiquity' new nations have accorded themselves (Anderson 1991: xiv) and indeed characterising his definition of the nation as posed in an `anthropological spirit' (Anderson 1991: 6), Anderson has downplayed the extent to which nationalism must also be rooted in, to use a much misunderstood term, a sense of the primordial character of a nation's heritage (however much the rise of that nationalism may be historically situated, as Anderson's first paradox implies). That is, the sense of a nation often demands a prehistory as well as a history, a sense of the continuity of cultural content from the earliest (imagined) origins. In short, the nationalist project tends to foster not only a history of recent foundational events, but an anthropological account of cultural evolution from an ancestral time when the basic values of national character were already nascent, even if awaiting codification by recent liberation movements and postcolonial regimes. Pace Anderson's assertion, in the quotation opening this paper, of the impossibility of a nation writing `down time', nationalist writers have been able to fashion `genealogical' accounts that assert the continuity of a nation's identity from the earliest times revealed by archaeology and palaeontology. Public Anthropology in Indonesia: Koentjaraningrat and Ali Moertopo The case of Indonesian nationalism provides an interesting exemplification of this ability. In many ways Indonesia has formulated its own social sciences based on the national civic philosophy of Pancasila, the five principles first articulated by Sukarno as part of the nationalist platform and later re-energised by Suharto's New Order as the basis of its developmentalist ideology: `monotheism, humanitarianism, the unity of Indonesia, leadership through consensus and representation, and social justice'2. Although Mubyarto's Pancasila economics is perhaps the most famous example, the anthropological perspectives put forward by the recently deceased doyen of Indonesian anthropology, Professor Dr. Raden Mas Koentjaraningrat, have in many ways constituted a Pancasila anthropology. Besides his work on ethnicity, rejecting a conflict model and emphasising how ethnic identity may conduce to national unity rather than seeking to topple it, Koentjaraningrat has in various ways sought to reconcile cultural diversity and local values with development as well, thus underscoring the fundamental process which the New Order has sought 2 In Indonesian, Pancasila reads as follows: `Ketuhanan Yang Maha Esa, kemanusiaan yang adil dan beradab, persatuan Indonesia, dan kerakyatan yang dipimpin oleh hikmat kebijaksanaan dalam permusyawaratan / perwakilan, serta dengan mewujudkan suatu keadilan sosial bagi seluruh rakyat Indonesia' (Moertopo 1973: 32). page 3 as its rationale (e.g. Koentjaraningrat 1974, 1977, 1993). Indeed, he even ends his monumental history of anthropological theory with a section entitled the `The position of Anthropology in Indonesia's Development' [Kedudukan Antropologi dalam Pembangunan Indonesia] (Koentjaraningrat 1990: 281-285). He has paid particular attention to the position of the so-called `most isolated tribes' (suku terasing), which have been subjected to considerable pressure to raise themselves, or at least to be raised, to general societal standards of health, education and economic development set by the government. As Koentjaraningrat (1993: 10) puts it, the official policy of the government is to `raise' them from their isolated status and develop their society so that they can be the same as the societies of other ethnic groups, orienting to the national culture of Indonesia. He has suggested that because of the very heterogeneity of conditions of the peoples in question, the term suku terasing is inappropriate and should be replaced by `suku-suku bangsa yang diupayakan berkembang', `the ethnic groups for whom efforts are being made to develop' or simply `suku bangsa berkembang', `the developing ethnic groups' in analogy with `the developing nations' (Koentjaraningrat 1993: 1). Koentjaraningrat's vision of anthropology, including its contribution to the developmentalist project, has been largely articulated in regard to the current (i.e. synchronic) diversity of Indonesia's peoples. Although he has treated the theories of cultural evolution propounded by others (Koentjaraningrat 1987), he himself has been more comfortable as an ethnographer (Koentjaraningrat 1984, 1985) and theorist of the dynamics of culture in contemporary situations. The task of proposing a cultural evolutionary model for the nation of Indonesia was, however, taken up by another public intellectual, Lieutenant General Ali Moertopo (Krissantono 1991), one of the most prominent ideologists and spokespersons of the New Order from its founding. The facts of Ali Moertopo's career in the New Order are of secondary concern here, as what is relevant in this consideration of the nationalist project is the vision of Indonesia's cultural evolution articulated in his book Strategi Kebudayaan (1978). Earning his credentials as a revolutionary soldier and then in the Madiun affair and in operations against the Dutch in the late 40s, Ali Moertopo went on to oversee the much-debated Pepera (Penentuan Pendapat Rakyat) `referendum' on the integration of Irian Jaya in the early 60s, particpate in the `Confrontation' (Konfrontasi) with Malaysia, and engage in the Seroja Operation in East Timor. Throughout these later campaigns, he was actively involved in the intelligence section of the armed forces (in Moertopo's case the term `military intelligence' does not seem an oxymoron), and came to serve as Suharto's private assistant. In 1971 he ignited the GOLKAR campaign with his concept of `The Acceleration and Modernisation of 25 Years' Development' [Akselerasi Modernisasi Pembangunan 25 Tahun] (Moertopo 1973b). While rising in the intelligence [BAKIN] services, he became a member of the organising committee of GOLKAR, the Government party, and rose to become the Information Minister in the third development cabinet page 4 (1978-1983), while retaining the position of deputy headin BAKIN. During his tenure in this position, he liberalised film imports, oversaw a program (`Koran Masuk Desa'--Benedict Anderson would be delighted at this confirmation of his conceptualisation of nationalism) of distributing newspapers in villages, especially military publications. Leaving this position in 1983, he became the deputy head of the Supreme Advisory Council (Dewan Pertimbangan Agung). However, besides his accomplishments as a military and administrative `operator', as well as a political visionary for GOLKAR (the `floating mass' concept was articulated and implemented while he was one of the party leaders) and the New Order (he saw one of his main tasks as presenting President Suharto's policies in intelligible terms to the common people), Ali Moertopo was also well-known as a public intellectual. In line with his vision for the need for a `think-tank' or `ideas factory' for the Indonesian nation (Krissantono 1991: 140) he founded (memprakarsai) the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in the early 70s. His publications, most of them appearing under CSIS auspices, largely dealt with issues of national security and strategy (e.g. Moertopo 1973a). Indeed, if one word epitomises the career and thought of Ali Moertopo, it is the term `strategic'. Not surprisingly, this term recurs in his (1978) book Strategi Kebudayaan (translatable as Strategies of Culture). While the latter part of this book focuses on development strategies for realising the potential of Indonesian culture, it is the early chapters of this book that are of the most relevance for exemplifying the anthropological aspects of the nationalist project. For Strategi Kebudayaan (hereafter referred to as SK) articulates a full-blown theory of cultural evolution, which situates the developmentalism of the New Order Indonesian state based upon the ideology of Pancasila as the teleological realisation of a process of cultural evolution that has characterised Indonesian society from its archaic or `antique' beginnings. Ali Moertopo's Basic Anthropological Concepts Moertopo begins his account by defining his basic terms. Culture (kebudayaan) he views as the process of humanity `developing a continual struggle in order to secure the victory of the process of humanisation and avoid the process of dehumanisation' (`manusia mengembang perjuangan yang terus-menerus untuk memenangkan proses humanisasi dan menghindarkan diri dari proses dehumanisasi') (SK: vi). Culture is thus an important force or power (kekuatan) in human history, but one that is not transcendental, but rather summarising human efforts or struggle. The power of culture is the power of human resource potentials. Culture cannot be seen in terms of any determinism exercised from outside, but as the expression of human power or agency. This force of human potential from `within' encompasses mental attitudes, values for life, ways of thought, ways of working, logic, aesthetics and ethics (sikap mental, nilai hidup, cara berpikir, cara kerja, logika, estetika, dan etika) (SK: 12). These provide the capacities for human beings to make the choices that constitute their process of humanisation. page 5 Strategies, which he derives directly from the Greek stratos (troops) plus agein (lead), brings the idiom of war into is account of culture3, leading to a definition that stresses the element of human agency in effecting change: `matters that have do do with the means and efforts to control and use all the resources of a society, a nation, to achieve its objectives' (hal-hal yang berkenaan dengan cara dan usaha menguasai dan mendayagunakan segala sumber daya suatu masyarakat, suatu bangsa, untuk mencapai tujuannya).4 From the very beginning Moertopo's foundational definitions resonate with New Order priorities and conceptualisations. The very definition of culture identifies it with a process of development (perkembangan), seen as the result of human `struggle' (perjuangan), one of the key idioms of Indonesian nationalist imagery, which has been channeled during the New Order not into anti-colonial struggle but into economic development and modernisation. As we shall see, the developmental process of cultural evolution finds its fruition in the explicit process of Development (pembangunan)5, seen as guided by human agency, of the New Order. Indeed, Ali Moertopo himself notes that his definition of culture hearkens back to the Indonesian Constitution (UUD) itself, specifically to paragraph 32, where `national culture' (kebudayaan nasional) is defined as a process of `heightening the degree of 3 Elsewhere I have written about martial idioms as an important component of Indonesian conceptualisations of development: A curious document issued by the Department of Agriculture of the province of South Sulawesi in Indonesia chronicles the search for a fitting public name for the program intended to accelerate rice intensification efforts in the three regencies of Bone, Bulukumba, and Sinjai. The program's official name `Operasi Khusus Peningkatan Produksi Pangan di Sulawesi' (`The Special Operation of Increasing Food Production in Sulawesi'), with its emphasis on the term operation, announces the military cast of this effort. Indeed, the organizational structure of the operation is given as a network of posts, the channels of communication between levels of implementation as `commando lines', its leaders as `attackers', and its measures as `shots'. The introduction to this document describes the program as a `campaign' aiming at a `breakthrough' that will lead other regency governments to adopt the lightning (with intentional echoes of Blitzkrieg?) measures leading to `short-cut increases of production.' (Dinas Pertanian Tanaman Pangan 1982) As the head of the provincial agriculture department quotes in the introduction to this document, `There is no success without struggle, and there is no struggle without sacrifice.' [`Tidak ada sukses tanpa perjuangan dan tidak ada perjuangan tanpa pengorbanan' (I).] The military idioms used to describe and implement this program are nothing new in Indonesian development rhetoric. Economic development in the New Order, and within that rubric the rice intensification program, is seen as a continuation of the nationalist revolutionary struggle for independence, calling for the same fervent commitment and martial tenacity (Acciaioli 1997: 292-293). 4 The term bangsa can be translated equally well as either `nation' or `people'. I will use either, according to the context, but when the term `people' is used, it should be remembered that we are still focussing on the concept of nation. 5 Hereafter I shall use the typographic convention of distinguishing the overall process of development as the unfolding of sociocultural evolution as development, beginning with lower-case `d' and Development, beginning with upper-case `D', as the government-led process of economic modernisation. page 6 humanity of the Indonesian people' (mempertinggi derajat kemanusiaan bangsa Indonesia) (SK: 10). The very emphasis upon human agency in effecting cultural development as a process of humanisation in Ali Moertopo's framework is further reinforced by the continual resort to the verbal form membudaya[kan], `to civilise', or to `to culturalise, to make part of one's culture'. The use of an active, transitive verbal form foregrounds the exercise of human powers in effecting development, as acknowledged by Ali Moertopo himself (SK: 10) in justifying it over the related intransitive term berkebudayaan, `to have or exhibit culture'). It also echoes the analogous use of such active verbal forms (e.g. `sciencing', `minding', `symboling') in the cultural evolutionary schemes of the anthropologist Leslie White (1949) and the archaeologist V. Gordon Childe (1951).6 It also echoes the continual use of this same term in Indonesian development programs and governmental regulations, where citizens are exhorted to `culturalise' or `make part of their own culture' (membudaya[kan]) such conditions of orderliness as observing traffic regulations or following the proper rotation of rice crops. Before proceeding to his evolutionary framework, Ali Moertopo presents various schemas for analysing the components of culture. Culture is divided into three basic relational dimensions which can be developed: 1) relations with one's fellow human beings 2) relations with the surrounding natural world (alam) 3) relations with God (Tuhan Yang Maha Esa) (SK: 11-12) As we will see, Moertopo believes that Indonesian culture, in its emphasis upon spiritual elements of culture, has tended to highlight the first and third relational dimensions throughout most of its evolution, while relatively ignoring the second until the advent of the modern age in its `National Resurgence'. In addition to these three dimensions, Ali Moertopo asserts that culture has seven basic elements (unsur) or systems. Moertopo's analysis of culture as consisting of seven universal elements of culture probably derives in part from Koentjaraningrat's own popularisation of the universal culture concept for Indonesian audiences. In the first three months of 1974 Koentjaraningrat ran a series of articles in the Jakartan daily newspaper Kompas, in which he addressed in a relatively nontechnical language `problems of mentality and development' (masalah mentalitet dan kebudayaan) from an anthropological perspective. In the first of these articles, assembled later that year into a semi-popular collection (Koentjaraningrat 1974), he listed the seven elements of culture as follows: 6 Ironically, both these figures base their emphasis upon the active capacities of humankind to make its own history on the humanism of Karl Marx, a source from which Ali Moertopo would be quick to dissociate himself. page 7 The universal elements of culture, which at the same time constitute the contents of all the cultures that there are in the world, are: 1) The religious system and religious cerermonies 2) The social system and organisation 3) The system of knowledge 4) Language 5) Art 6) The system of livelihood 7) The system of technology and equipment [Unsur-unsur universel itu, yang sekalian merupakan isi dari semua kebudayaan yang ada did dunia ini adalah: 1) Sistem religi dan upacara keagamaan 2) Sistem dan organisasi kemasyarakatan 3) Sistem pengetahuan 4) Bahasa 5) Kesenian 6) Sistem mata pencaharian hidup 7) Sistem teknologi dan peralatan] (Koentjaraningrat 1974: 12) As revealed in his somewhat earlier (lst edition, 1967) introductory textbook in Social Anthropology, Koentjaraningrat (1977) himself adopted these seven elements from Kluckhohn's (1953) universal categories of culture. However, Moertopo's list is as follows: 1) the knowledge system (sistem pengetahuan 2) the technological system (sistem teknologi) 3) the economic system (sistem ekonomi) 4) the social system (sistem kemasyarakatan) 5) the linguistic system (sistem bahasa) 6) the religious system (sistem religi) (SK: 12) Interestingly, despite his assertion of seven basic elements, he only includes 6 in his list. The oversight is not insignificant, for later in his text (see below) his proclaimed list of the seven elements of culture once more only includes six, but not exactly the same six as here. In this context, the following discussion in the text tends to differentiate language (bahasa) from literature (sastra), thus implicitly completing the list of seven, with literature (sastra) substituting for art (kesenian) from Koentjaraningrat's complete list. However, accounting for the somewhat variant listing of six elements later in Ali Moertopo's text requires examining his evolutionary progression. However, before proceeding to this framework Ali Moertopo feels compelled to specify the `subject' of this cultural apparatus. That is, he feels the need to characterise the `Indonesian nation' (bangsa Indonesia) whose cultural evolution he is to trace. Although declared a cultural subject in the proclamation of independence and constitution (SK: 13), Ali Moertopo conceptualises this nation as page 8 having had an enduring identity from well before this political assertion, indeed from antiquity. The Indonesian nation has been shaped by its basic environmental characteristics as an archipelagic society (masyarakat nusantara) (SK: 14), one justly labelled as `our land and sea' (tanah air kita).7 In terms that border on environmental determinism, thus setting up a theoretical tension with his earlier emphasis upon human agency, Moertopo describes how this archipelagic positioning has caused certain directions to be taken in cultural evolution: This environment of a "completely archipelagic" character has caused the culture which has developed here also to have an "archipelagic" design. That which is named "archipelagic culture" certainly has differences from "continental culture". In addition, the earth, sky, water and climate found in this region constitute conditions that contribute to giving form to the development of culture in Indonesia. The fertility of the archipelagic land has resulted in the archipelagic society developing to become a farming society. The relationship of humanity with the land constitutes quite an important factor. [Lingkungan alam yang bersifat "sarwa-nusantara" itu menyebabkan bahwa kebudayaan yang berkembang di sini juga mempunyai corak yang 'nusantara'. Apa yang dinamakan "kebudayaan nusantara" tentu saja mempunyai perbedaan dengan "kebudayaan darat" (continental culture). Selanjutnya bumi, langit, air, iklim yang terdapat di wilayah ini juga merupakan kondisi yang ikut memberi bentuk pada perkembangan kebudayaan Indonesia. Suburnya tanah nusantara mengakibatkan bahwa masyarakat nusantara berkembang menjadi masyarakat pertanian. Hubungan manusia dengan tanah merupakan faktor yang sangat penting] (SK: 14). Thus, Indonesia's basic cultural heritage can be labelled an `aqua culture' (SK: 15, Moertopo's own English term8), as opposed to a `terra culture' (SK: 15), setting the ways in which Indonesian society has recognised natural forces and used natural resources. In fact, Ali Moertopo sees contemporary cultural strategies in Development programs as needing to emphasise how further to `culturalise' its inherent `aqua-culture' (membudayakan aqua culture) (SK: 16). For further elaboration of this notion of archipelagic culture, see Acciaioli (2001, n.d.). Taylor (1994) has illustrated how the notion of ‘archipelagic culture’ (kebudayaan Nusantara) has informed the layout of regional museums throughout Indonesia. More recently, in the last national election (2008) the Archipelagic Republican Party (Partai Republika Nusantara or RepublikaN) had as a key plank of its platform the changing of the name of the country from Indonesia to Nusantara. 8 Ali Moertopo demonstrates throughout the text his penchant to invoke words from many languages, at times constructing macaronic terms. In this context, it is interesting that he avoids the term `evolution' and its Indonesianised form evolusi, perhaps because of the atheistic connotations of a term associated both with Darwin's biological theory and with anthropological theories influenced by Marxism. 7 page 9 In addition, the position of this archipelago at an important point of intersection of the world's (commercial) traffic has, of necessity, made Indonesia an open culture' (terpaksa menjadi kebudayaan yang terbuka). However, its openness to forces for change from outside should not be identified with a passive stance. Ali Moertopo identified the ability to engage in `acculturation' as one of the primary strengths of this archipelagic society and culture (`akulturasi nampaknya telah selalu menjadi kekuatan pokok masyarakat dan kebudayaan nusantara ini') (SK: 16). Even before its codification as a theoretical concept (Redfield, Linton and Herskovits: 1936), acculturation had long been a focus of culture change in various American approaches in anthropology. Voget summarises various positions with the following definition: Acculturation: the process of intercultural exchange between two societies, involving persistent and interpenetrative change and accommodation over a prolonged period of time. The term usually is applied to contact situations where one society possesses a more complex culture and dominates the intercultural process (Voget 1975: 861) However, furthering the arguments posed by van Leur concerning active construction of society in the Indonesian archipelago, rather than its position as simply a passive recipient of waves of influence from outside (Leur 1967) and in keeping with his own emphasis upon indigenous agency, Moertopo rejects the connotations of passivity and domination/inferiority indicated by Voget. He accomplishes this reconceptualisation by emphasising how acculturation is always complemented by a process of enculturation (enkulturasi). Rejecting (or perhaps unaware of?) the usual definition of enculturation as the process of cultural transmission across the generations (e.g. from parents to children), hence largely a synonym for socialisation (Williams 1972), Moertopo characterises enkulturasi as a creative refashioning of elements as they are made over in the image of the local culture. The akulturasi/enkulturasi nexus thus insures that outside influences are never passively received; the priority of active human agency within the refashioning culture is thus maintained. Ali Moertopo's Cultural Evolutionary Model With these understandings in mind, we can now proceed to a brief characterisation of Ali Moertopo's schema of Indonesian cultural evolution, which I have summarised in Figure 1. Indonesian prehistory can only be reconstructed from the remains of so-called Java Man, as discovered in Solo, Ngandong and Wajak. Little can be said about the culture at this time, but even these remains indicate that the archipelago was already a `crossroads for cultural migration' (persilangan migrasi kebudayaan). Despite this foundation for continuity, this prehistoric period (jaman prasejarah) needs to be distinguished, at the highest level of contrast, with all subsequent periods, which constitute a `post-prehistoric period' (jaman post prasejarah)9. The first period within this more general category is that of proto9 The term `historical period' (jaman sejarah) would perhaps be a bit problematic, because the next ensuing period is not characterised throughout its length by the possession of writing. page 10 Indonesia or ancient Indonesia (Indonesia purba)10 This period marks the beginnings of the archipelagic society and culture, as signaled by the onset of sedentarisation11. It is in this era that the essential foundations of Indonesian culture are laid, the constitution of the `cultural subject' (subyek budaya) whose continuous development Ali Moertopo traces to the present. Because of the lack of writings, this period is known only from external mentions and reports, such as Ptolemy's mention of Jabadiou (Jawadwipa) and the Khersonesos or Golden Island, and Chinese records of Ye-po-ti (SK: 18). Once more the framework of seven basic elements is adduced for this originary archaic culture, but as opposed to the merging of art within language (and perhaps religion) in the earlier listing (SK: 12), here the listed elements cover knowledge about the natural world, technology, the social system, language and literature, art, and the religious system. In most cases the evidence of the foundational developments in these subsystems of culture must be indirect. For example, the systematisation of knowledge about the natural world is evident in developments in sailing, agriculture and animal husbandry (SK: 20). Likewise, technology, in which the (unmentioned, at this stage) economic or livelihood system appears merged, is evident in farming, animal husbandry, coinage, defense, and the use of such equipment as the bow and arrow. All these indicate a mastery of the natural world (menguasai alam) and an ordered economic system (sistem perekonomian teratur). The social system has developed by this time a number of ways of reckoning descent--matrilineal, patrilineal and `parental' (i.e. cognatic?)--as well as a division of labour and proto-democratic political system. Local wisdom is embodied in oral literature, encompassing such genres as aphorisms, poems, proverbs, parables and others. All these indicate the operation of a consciousness or mentality makred by `deep reflection concerning the life of this humanity' (refleksi yang mendalam mengenai kehidupan manusia ini) (SK: 21). Indeed, these can be said to constitute a system of literature. Art is tied to religion, with its magic and sacral elements, connecting to the mysterious spiritual forces, as well as to the social system it serves. Ali Moertopo thus weaves together a picture of this era that exhibits the anthropologically vaunted functional consistency, with all the subsystems functioning to support the whole society. 10 Anderson might appreciate the translation `antique Indonesia' given his highlighting of the `antiquity' of the nation as conceived in nationalist movements (Anderson 1991: xiv). The term purbakala means antiquity, and dinas purbakala is used for the archaeological service. 11 The importance of sedentarisation in such development policies as the local transmigration or resettlement of the `most isolated peoples' (masyarakat terasing) is, no doubt, of importance in Ali Moertopo referring to sedentarisation as an index of the foundations of archipelagic culture and society. page 11 He also posits for this era a basic belief in the One Great God as the highest spiritual power, thus adopting a stance reminiscent of the Kulturkreislehre of Father Wilhelm Schmidt (1939), which sought to discern a primeval monotheism in the oldest layers of culture to be found throughout the world (e.g. among the `pygmies' of the Malay peninsula and the African Congo, as investigated by his disciple Paul Schebesta). Yet, it is perhaps not due to his adherence to this former diffusionist school of anthropology, but the necessity for this New Order ideologist to assert the prefiguration of the first great principle of the contemporary Indonesian society in which he served that motivates this observation. The first principle of Pancasila asserts the belief in the one Great God (Tuhan Yang Maha Esa). In order for Ali Moertopo to maintain his position of continuity from the basic foundations of archipelagic Indonesian society in this proto-period right down to the present-day New Order, it is thus necessary for him to assert the existence of this monotheistic belief in this era of cultural foundations. Significantly, it is in this period of archaic Indonesia that Ali Moertopo traces the emergence of local drama plays (wayang) (e.g. shadow puppet plays) as an indigenous art form that embodies reflections upon the social condition. He thus rejects its foreign origin in the ensuing period, that of Hindu influence (jaman pengaruh Hindu). While acknowledging the absorption of themes and characters from Hindu traditions, wayang as an indigenous tradition is an arena for the process of endogenous enculturation that complements the acculturative introductions from abroad. However, he does acknowledge the introduction of Hindu influences on several of the subsystems of culture. The social system absorbed the rise of Hindu realms (kerajaan), but even these were not just instituted through acts of acculturative `subjection' (penaklukan), but were endogenous developments of the archipelagic customary communal society. Nevertheless, perhaps as an effect of the Hindu caste system, the local social system became differentiated into three domains (lingkungan), almost like Western estates, that is, the palace rulers (ksatria), the religious functionaries, and the common people (rakyat). Although trade provided one channel of entry, Hindu influence had little effect on the subsystems of knowledge, technology, and economy. Rather, it was the religious subsytem that was the constitutive factor at this time. Similarly, although accepting the notion of the alphabet and aspects of Sankrit literature through acculturation, through enculturation the archipelagic society fashioned Javanese or Indonesian literature12 and maintained the structure(s) of its archipelagic language intact despite Sanskrit influences. Similarly, in the subsytem of art Hindu motifs (corak) became prevalent, but the basic forms remained archipelagic (i.e. 12 The identification of Javanese literature with a generic Indonesian literature once again bears witness to the processes of Javanese hegemonisation in the New Order. Ali Moertopo himself was a Javanese Muslim, though apparently not of a strictly reformist orientation. Ironically, the think-tank he founded, the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, has more recently been seen as a haven for Christian intellectuals, often Chinese, whose essential Indonesianness has sometimes been questioned. page 12 endogenous). Ali Moertopo does acknowledge a greater degree of change in the religious system, as the primal animism or dynamism, based however on an underlying belief in the One Great God, was partially transformed into a system of gods (idols?) (sistem dewa-dewa) due to the new rulers tracing their descent from these deities and to the influence of the Hindu religious system in such epics as the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Yet, once again in a striking analogy (adherence) to the principles of Pater Schmidt's theory of Ur-monotheism, Moertopo maintained the underlying continuance of belief in the One Great God from its position in the originary archipelagic society. In short, although the coming of Hindu influence produced acculturation, the `archipelagic society and culture remained steady as a subject developing [on its own], enriching itself with elements of Hindu culture' [`masyarakat dan kebudayaan nusantara tetap sebagai satu subyek yang berkembang, memperkaya diri dengan unsur-unsur kebudayaan Hindu itu'] (SK: 25). Despite the onslaught local agency was preserved; the identity of the archipelagic subject remained. With its many similarities to the Hindu period in such aspects as the process of entry (i.e. through trade), the era of Islam in Indonesia is characterised by Ali Moertopo in much the same fashion. Hindu kingdoms (kerajaan) yield to Islamic sultanates (kasultanan) in the social realm, just as Arabic literary forms--hikayat, babad13, etc.--enter the system of language and literature, and the characters and plots of wayang are enriched by Islamic figures and plots. The three basic social estates remain--the palace rulers, the religious functionaries (although ulama now replace pedanda), and the common people, although he suggests that a fourth grouping--traders--may have gained a more institutionalised presence. Despite the obvious influence of Islamic motifs and institutions, continuity rather than discontinuity, though not without tension or conflict, characterises the transition. It is a shift of `atmosphere' (suasana) from the Hindu to the Islamic, an enrichment, but not a transformation of the fundamental cultural subject. Just as one cannot really speak of a process of Hinduisation (Hinduisasi), so there is no real Arabisasi14. However, the ensuing period does mark a rupture of a sort. The confrontation with the West, most notably the colonial domination by the Netherlands, but also encompassing the encounter with other Western countries, such as Portugal, Spain, and England, was the first instance of a meeting of cultures whose basic designs (corak) were fundamentally different. Although acknowledging the religious influence of the Christian and Catholic missionary projects (labelled Zending and 13 I am not sure that babad as a literary genre can be traced to Arabic influence. Perhaps this is an oversight on Moertopo's part, whose enthusiastic scholarship is sometimes a bit sloppy with details. 14 One wonders whether he uses the term Arabisasi instead of Islamisasi here to avoid the ire of Indonesia's Muslim constituency. page 13 Missie respectively), Ali Moertopo emphasises the dominance of physical and material channels of impact, with the economic motives of the Westerners overriding other grounds of encounter. But instead of a process of absorption and refashioning in the archipelagic image that characterised the acculturation/enculturation nexus of the previous Hindu and Islamic periods, in the Hindia Belanda period there developed a process of dualism, of two cultures, archipelagic and Western, developing side-by-side, but not really interpenetrating (SK: 28). The archipelagic society and culture continues along its own path of endogenous development, but in its midst come the symptoms (gejala)--and this term symptoms is itself symptomatic of the lack of internal connection--of the West. As Ali Moertopo theorises this new contact situation, of the three types of social contact--associative (asociatif), leading to integration; juxtaposing (iuxapositif), leading to side-by-side accompaniment; conflictive (konfliktif), leading to oppposition--this era was characterised mainly by the second juxtaposing, side-byside mode15. In part, this mode of encounter dominated because the new impinging culture emphasised the subsystems of (natural or empirical) knowledge, economy, and technology, whereas the preceding influences concentrated upon the religious, linguistic, social, and aesthetic subsystems of culture that the local archipelagic subject had itself tended endogenously to develop. Interestingly, it is only at this point in the text that Ali Moertopo beings explicitly to distinguish the economic or livelihood subsystem from the technological system, which had been merged in his previous listing, thus finally delivering his theoretical promise of analysing seven elements of culture. It is this very dualism of the Hindia Belanda era that motivates the transition to the final era, that of national resurgence or awakening (Kebangkitan Nasional16). While the Dutch fostered and defended this disparity of development in regard to (empirical) knowlege, economy, and technology, the Indonesian subject(s), ever exercising their own agency, were able to gain a `new awareness' (kesadaran baru) of this dominance. Indeed, Moertopo suggests that an alternate name for this final period could be the `era of awareness' (Jaman Kesadaran) (SK: 29). Although the Oath of the [Indonesian] Youth17 in 1928 marks the formal beginning of this 15 By implication the dominant mode of encounter of the two preceding periods would have been the associative, although Ali Moertopo himself does not state this contrast explicitly. 16 It is interesting to note that beginning at this point in the text the term `national' (Nasional) tends to replace `archipelagic' (Nusantara). 17 This oath runs as follows: We, sons and daughters of Indonesia, declare that our homeland/sea is one, the homeland/sea Indonesia We, sons and daugher of Indonesia, declare that we are one nation (i.e. people), the Indonesian nation We, sons and daughters of Indonesia, declare That we speak one language, the Indonesian language. [Kami, putera-puteri Indonesia, menyatakan page 14 phase, once again Ali Moertopo emphasises that it did not mark an `historical discontinuity' (bukanlah satu diskontinuitas sejarah) (SK: 29). Rather, it expressed a culminating point in a phase-by-phase development of the strength of archipelagic culture. For nationalism was a cultural development before it was a political development, as evidenced by the origins of the nationalist movement in educational and social associations, as well as religious and regional movements. Invoking, approrpriately enough given his emphasis upon `aqua-culture', the metaphor of a flowing river gaining its water from many creeks, Moertopo notes how these movements all then `converged in the national estuary of unity, nationalism, and Unity in Diversity' (bermuara pada kesatuan, nasionalisme, Bhinneka Tunggal Ika)18 (SK: 29). Although a product of continuous evolution, this national awakening does mark a new level of cultural development. Previously, there had been the continuously evolving `archipelagic culture' (kebudayaan nusantara); now there was a consciousness (kesadaran) of this culture on the part of its people and of itself as `one nation'19 residing in one archipelago, experiencing one environment and geographical condition, speaking one language, and in one demographic condition: in short, consciousness of a unitary subjecthood. This awareness marks an expansion of the place of Indonesia, as it becomes directly a part of the history of the world: The National Resurgence certainly constitutes a trunk in the history of culture. Because from that awareness began a generative cultural process of the archipelagic society in a more extensive wheel of society, the wheel of a modern global history. This process is certainly not an easy one. It is a process of struggle. It is a process that is fraught with issues and problems. [`Kebangkitan Nasional sungguh merupakan satu tonggak sejarah kebudayaan. Sebab dari kesadaran itulah, terjadi proses generatif kulturil masyarakat nusantara di dalam roda sejarah yang lebih luas, roda sejarah dunia modern. Proses tersebut memang bukanlah proses yang bertanah air satu, tanah air Indonesia Kami, putera-puteri Indonesia, menyatakan berbangsa satu, bangsa Indonesia Kami, putera-puteri Indonesia menyatakan berbahasa satu, bahasa Indonesia] 18 The national motto Bhinneka Tunggal Ika' is, appropriately enough, an adage from old Javanese usually translated as `Unity in Diversity', although more literally it can be rendered as `divided it is one' (Soebadio 1985: 11). Soebadio explains that the motto is taken from an Old Javanese manuscript source, perhaps originally, from the 11th century A.D., the Sutasoma. 19 One cannot help but remark the analogy here to the Hegelian notion of Absolute Spirit achieving consciousness of Itself through history. This Hegelian climax gives a new twist to Ali Moertopo's own labelling of his task at the beginning of this work by the German term Aufgabe. page 15 mudah. Ia adalah proses perjuangan. Ia adalah proses yang ditempa oleh berbagai peristiwa dan permasalahan] (SK: 30).' While beginning in the colonial period, this era reached its definitive form during World War II, for then it made the transition from being a cultural to a political movement, achieving expression in the Declaration of Independence of 17 August 1945. For Ali Moertopo this declaration was not just a political act, but a declaration, once again, of the identity of the cultural subject: the archipelagic society and culture (SK: 30). As the description of this final period of Indonesian national identity and awareness makes clear, Indonesian cultural evolution finds its teleological fulfilment in the Era of National Resurgence. Ali Moertopo proceeds to describe various phases of this era, from the achievement of independence to the culmination of nationalism in the New Order government of President Suharto. (Not suprisingly, given his own position in the New Order, the achievements of the Old Order under Sukarno are not dwelled upon!). Once more the New Order is treated not primarily as a political regime, but as another phase in the basic cultural evolution of the Indonesian cultural subject: The New Order is a cultural process. It is a new manifestation of the fundamental dynamic of the archiplagic people and the archipelagic culture.' [`Orde Baru adalah proses kebudayaan. Ia adalah manifestasi baru dari dinamika dasar masyarakat nusantara dan kebudayaan nusantara.'] (SK: 36) In fact, the developmentalism of the New Order may be seen as a further heightening of the awareness of the Indonesian people as a cultural subject. Its policies of Development constitute a harnessing of the inevitably unfolding process of cultural development in the archipelago in terms of the conscious plans of socioeconomic Development that bring to fruition the largely unconscious `strategies of culture' of past phases. The New Order emphasis upon economic development and modernisation Ali Moertopo sees as a necessary strengthening of the three cultural subsystems of (empirical, scientific) knowledge, economy and technology, the three elements most neglected in the earlier eras of Indonesia's cultural evolution and the consciousness of whose importance during the immediately preceding Hindia Belanda era spawned the final Era of National Resurgence. Only in this modern age have these factors become dominant, redressing the previous imbalance and leading to changes in the social, linguistic artistic, and religious systems. Perhaps one of the best indications of the closure, however tentative, that Ali Moertopo feels the final era has brought to the process of cultural development is the very fact that only in this modern age does he realise textually the treatment of all seven elements of culture that he had originally announced as his analytical strategy.20 20 Although the remainder of the text goes on to detail the later stages of the era of national resurgence and the particular `cultural strategies' of the New Order government that have been essential in bringing about the Indonesian nation's realisation of its destiny, limitations of space here page 16 Conclusion: The Evolutionist Nationalism of Ali Moertopo Ali Moertopo's approach to delineating the continuing identity of the Indonesian nation in a process of cultural evolution is not unique. In many ways he has been only one of the many New Order ideologists to articulate such a schema, which has been more implicit in the speeches and writings of other leaders. Others have emphasised as well the cultural aspects of Development for the Indonesian nation. Indeed, cultural Development has also been one of the priorities of the New Order state. In the words of Haryati Soebadio, a former Director-General of Culture: National cultural development is acknowledged as being the basis for national development in general. Indonesia gives priority to the development of national culture to enhance cultural identity and national unity as outlined in the constitution and the state ideology. (Soebadio 1985: 59) Nation building in Indonesia has thus been centrally concerned with the cultural construction of the Indonesian nation. In fact, Article 32 of the 1945 Constitution, to which Ali Moertopo himself makes reference in Strategi Kedudayaan (SK:10), states explicity that `the Government shall develop the National Culture of Indonesia.' (Soebadio 1985: 18; see also Foulcher 1990: 301; Davis 1972) Many administrators have conceptualised this task as simply making explicit, recovering, or uncovering what some Indonesian scholars have labelled a distinctive `local genius' (Soebadio 1985: 11). This `local genius' is conceptualised as a substratum of culture shared by all peoples of `the entire archipelago [viewed] as a single socio-cultural unit'. (Writers' Group n.d.: 19) In this archipelagic concept, the cultural substratum consists of an already existing unitary repository of specifically cultural resources. In short, this `local genius' corresponds largely with the shared archipelagic culture whose identity and development as a cultural subject Ali Moertopo delineates. Various other aspects of Ali Moertopo's conceptualisation of Indonesian cultural evolution have also characterised other New Order proclamations. I have outlined elsewhere how the museum exhibition celebrating Indonesia's observance of the `Year of Indigenous Peoples' has encoded how this archipelagic notion of culture has contributed to the ability to conceptualise a cultural substratum for all Indonesia and hence to constitute a unitary Indonesian people (Acciaioli n.d.). Among other borrowings, as noted above, Ali Moertopo has obviously adopted his stress upon the importance of the mentality (mentalitet) of the Indonesian people for the process of cultural development, as well as many of his underlying notions of the dynamics of culture, from the Indonesian anthropologist Koentjaraningrat. Indeed, one may wonder if at an even more fundamental level this New Order preclude me from treating these sections fully. However, they add little in terms of anthropological concerns to the basic framework that he has elaborated in the previous chapters of his book. page 17 ideologist expresses in his model a shared outlook with his Javanese compatriots. Moralist that he is, Ali Moertopo continually emphasises the basic process of humanisation (humanisasi) that is the goal of cultural evolution, as well as the basic source of morality (SK: 72). As part of this process, he makes a fundamental division between the more spiritual aspects of universal culture--the subsystems of language, art, society (structure and organisation), and, above all, religion--and the more material elements--(empirical, scientific, natural) knowledge, technology and economy. He views the former subsystems as those which the archipelagic culture, the Indonesian people as subject, have most developed endogenously, while the development of the latter presents the challenge of which the Indonesian nation first became aware in the colonial era (Hindia Belanda) and which the Development policies of the New Order have been strategically designed to augment through modernisation. It is not hard to discern here an echo of the basic distinction between batin and lahir, inner and outer, spiritual and material, that provides the basic polarity of Javanese, and perhaps more widely Indonesian, practices of spiritual devotion. Ali Moertopo's avoidance of materialist explanations, and indeed of the term evolution (evolusi) itself, as well as his avoidance in elaborating the prehistoric stage that begins his evolutionist framework, may perhaps be due as much to his Javanese intellectual heritage as to the New Order paranoia of intellectual frameworks that may smack of atheism, and hence Communism. It is important to stress, in addition to some of the Javanese, if not Indonesian, particularities of Ali Moertopo's text, some of the more general characteristics of such an account. After all, he himself grounds his text in a model of universal categories of culture. Perhaps a distinction made most forcefully by the philosopher Stephen Toulmin (1972) is most appropriately invoked here. Toulmin posits a basic distinction between evolutionary and evolutionist accounts. Whereas the former view the changes that cumulate in the process of evolution as responses to particular historical situations, hence depending upon notions of, or at least analogues to, adaptation, the latter postulate changes as the realisation of a master pattern that lies in or above history.21 In its constant reiteration of the continuity of the development of the archipelagic subject, its emphasis upon endogenous development in the face of exogenous influences, and its teleological fruition in the era of national resurgence, especially as culminating in the New Order, Ali Moertopo's schema of cultural development is firmly evolutionist rather than evolutionary, despite his stress upon human agency in the process. Of course, it is not unique in this regard. Many nineteenth-, and even twentieth-century schemes of cultural evolution and universal history are similarly evolutionist, that of 21 Such a distinction is not unique. Maurice Mandelbaum (1971) posits a similar distinction between functional laws, which explain historical changes as the result of particular historical factors operating in various ways within unique sets of constraints, and directional laws, which assume `historical change is to be represented as a process of natural development or unfolding, one in which the historical transformation of an entity occurs as the result of the actualization of the potentialities inherent in that entity from the very beginning' (Sanderson 1990: 17). page 18 Spencer in the previous century and Toynbee in the twentieth, to name but two salient exemplars. Indeed, the analogy to Spencer's general--one might even say metaphysical-evolutionist position, with its underlying notions of `unfolding relations' and `logical development' (Sanderson 1990: 20) reveals another dimension of the evolutionist perspective: its ideological work. Spencer did not simply articulate an abstract schema of the development of all aspects of the universe from the homogeneous to the heterogeneous in an overall process of evolutionary `survival of the fittest'. He also drew very specific practical conclusions from his framework. As an apologist of laissez-faire capitalism, an advocate of voluntarism and minimal government, he emphasised, for example, `the importance of individual liberty and a limited State as the pre-condition for the development of each individuals' [sic] innate faculties' (Taylor 1992: 116). He also declared in some writings how education was valuable only insofar as it taught skills essential to self-preservation, and education devoted to the cultivation of "tastes" and "feelings" was a waste of time' (Kuklick 1991: 107). Indeed, he was but one of many evolutionists whose work as public intellectuals emphasised implications for public policy. Other evolutionist thinkers, working from different frameworks, attempted to implement different social goals as the practical realisation of their evolutionist (and even evolutionary) theorising. John Lubbock, whose schema of evolution differed significantly from Spencer's, also asserted, in contrast to Spencer's stance on education, `Now we advocate Education...not merely to make the man the better workman, but the workman the better man' (Quoted in Kuklick 1991: 107). Indeed, Lubbock not only wrote such assertions, he actively served in government to implement them, including three royal commissions evaluating educational institutions and serving as the University of London's representative in Parliament. He worked to establish evening classes for modern workers, emphasising the teaching of modern languages and sciences to fill the spiritual vacuum of their lives. Such evolutionist thinkers regarded such practical institutions as vehicles for moral evolution, for the emergence of more productive forms of association and cooperation. Such work thus reveals the implicitly moral message of various evolutionist canons. In many ways, such figures provide precedents for returning to Ali Moertopo's work not simply as the exposition of an intellectual framework, the predominant perspective in this paper, but also as yet another of his quite practical writings as a New Order ideologist. Kuklick has noted how the nineteenth century social evolutionists wrote with a specific ideal society in mind: `In the aggregate, evolutionists worked to realize a specific goal: a society rationally managed, populated by a citizenry imbued with altruistic motives, a society that expressed the forces of history they identified' (Kuklick 1991: 106). Certainly, the particular society that Ali Moertopo has envisioned as the culmination of Indonesian cultural development, as realised most fully through the New Order's cultural strategies of page 19 modernisation and development, differs fundamentally from the laissez-faire capitalism that Spencer's theories did so much to promote in Victorian England. Moertopo’s ability to draw policy and strategies for Development (pembangunan) from his model of endogenous Indonesian cultural development (perkembangan) reveals the ineluctably moral and political nature of frameworks of cultural evolutionism. In this regard Moertopo’s political role as an agent of a coercive State, specifically the New Order regime of President Soeharto, should not be forgotten, especially his facilitation and promulgation of Indonesian (internal?) colonialism, both with respect to Irian Jaya and East Timor, as well as his role in the Intelligence sector, which undeniably facilitated the disappearance of thousands of opponents of the regime. Moertopo’s use of a model of cultural evolutionism that justified the regime in which he acted as the ultimate realisation of the Indonesian cultural subject provides a cautionary lesson concerning the uses to which anthropological frameworks of understanding as justifications of State policy can be put. page 20 FIGURE 1 The Basic Schema of Indonesian Cultural Evolution in Ali Moertopo's Strategi Kebudayaan (1978) Prasejarah [Prehistory] Post-prasejarah [Post-prehistory] (History?) Endogenous Development Contact (same elements of culture emphasised) Contact of similar cultures (Enrichment) PraProtosejarah Indonesia [Pre(Indonesia history] Purba) [ProtoIndonesia (Ancient Indonesia)] Pengaruh Hindu [Hindu influence] Modernisation (different elements of culture emphasised) Contact of dissimilar cultures (Dualism) Zaman Hindia Islam Belanda [Era of [Dutch Islam] colonial period] [National Kebangkitan Nasional (Zaman Kesadaran) Awakening (Era of Consciousness)] page 21 References Acciaioli 2001 ‘Archipelagic Culture’ as an Exclusionary Government Discourse in Indonesia. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 2(1): 2001-23. Acciaioli n.d. Exhibiting the Indigenous: Indonesian Government Representations of the Bajau. Unpublished paper prepared for the panel `THE POLITICS OF EXHIBITION IN SOUTHEAST ASIA', Asian Studies Association of Australia biennial conference, 8-11 July 1996, La Trobe University, Melbourne. Acciaioli, Greg 1996 Pavilions and Posters: Showcasing Diversity and Development in Contemporary Indonesia. Eikon 1: 27-42. Acciaioli, Greg 1997 What's in a Name? Appropriating Idioms in the South Sulawesi Rice Intensification Program. In Imagining Indonesia: Cultural Politics and Political Culture (Monographs in International Studies, Southeast Asian Series, No. 97). Jim Schiller and Barbara Martin-Schiller, eds. Athens OH: Ohio University Center for International Studies. Pp. 288-320. Anderson, Benedict 1991 Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. Revised Edition. London: Verso (1st ed., 1983) Childe, V. Gordon 1951 Man Makes Himself. New York: New American Library (1st ed., 1936) Davis, Gloria (ed.) 1972 What is Modern Indonesian Culture? Papers in International Studies, Southeast Asia Series, no. 52). Athens OH: Ohio University Press. Drake, Christine 1989 National Integration in Indonesia: Patterns and Policies. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. Foulcher, Keith 1990 The Construction of an Indonesian National Culture: Patterns of Hegemony and Resistance. In State and Civil Society in Indonesia (Monash Papers on Southeast Asia, No. 22). Arief Budiman, ed. Pp. 301-320. Clayton: Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, Monash University. Geertz, Clifford 1963 The Integrative Revolution: Primordial Sentiments and Civil Politics in the New States. In Old Societies and New States: The quest for modernity in Asia and Africa. Clifford Geertz, ed. Pp. 105-157. New York: The Free Press. Kluckhohn, Clyde 1953 Universal Categories of Culture. In Anthropology Today. A. L. Kroeber, ed. Pp. 507-523. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. page 22 Koentjaraningrat 1974 Kebudayaan, Mentalitet dan Pembangunan. Jakarta: Penerbit P.T. Gramedia. Koentjaraningrat 1975 Anthropology in Indonesia: A Bibliographical Review (Bibliographical Series 8). 's-Gravenhage: Martinus Nijhoff (for the Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde). Koentjaraningrat 1977 Beberapa Pokok Antropologi Sosial ( Pustaka Universitas No. 8). 3rd edition. no place [Jakarta?]: Penerbit Dian Rakyat. (1st ed., 1967) Koentjaraningrat 1984 Kebudayaan Jawa (Seri Ethnografi Indonesia No. 2). Jakarta: PN Balai Pustaka. Koentjaraningrat 1985 Javanese Culture. Singapore: Oxford University Press (under the auspices of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore) Koentjaraningrat 1987 Sejarah Teori Antropologi. vol 1. Jakarta: Penerbit Universitas Indonesia. Koentjaraningrat 1990 Sejarah Teori Antropologi. vol 2. Jakarta: Penerbit Universitas Indonesia. Koentjaraningrat 1993 Pendahuluan [Introduction]. In Masyarakat Terasing di Indonesia [Seri Ethnografi Indonesia, no. 4], ed. Koentjaraningrat and V. Simorangkir. Jakarta: Penerbit PT Gramedia Pustaka in cooperation with Departemen Sosial [The Social Affairs Department], and Dewan Nasional Indonesia untuk Kesejahteraan Sosial [The National Council for Social Prosperity]. Pp. 1-18. Koentjaraningrat and V. Simorangkir (eds.) 1993 Masyarakat Terasing di Indonesia [Seri Ethnografi Indonesia, no. 4]. Jakarta: Penerbit PT Gramedia Pustaka in cooperation with Departemen Sosial [The Social Affairs Department], and Dewan Nasional Indonesia untuk Kesejahteraan Sosial [The National Council for Social Prosperity]. Koentjaraningrat and Harsja W. Bachtiar, eds. 1963 Penduduk Irian Barat (Projek Penelitian Universitas Indonesia No. II). Jakarta: P.T. Penerbitan Universitas [Indonesia]. Kompas 1998 Tak Benar, Nenek Moyang Bangsa Indonesia dari Austronesia. Kompas Online (Kamis, 19 Februari 1998). http://www.kompas.com/9302/19/DIKBUG/tak.htm page 23 Krissantono 1991 Ali Moertopo di Atas Panggung Order Baru: Tokoh Pembangunan dan Pembaruan Politik. In Prisma: Edisi Khusus 20 Tahun Prisma 1971-1991. Pp. 136-157. Jakarta: LP3ES. Kuklick, Henrika 1991 The savage within: The social history of British anthropology, 1885-1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Leur, J. C. van 1967 Indonesian Trade and Society: Essays in Asian Social and Economic History. 2nd ed. The Hague: W. van Hoeve. Moertopo, Ali 1973a Indonesia in Regional and International Cooperation: Principles of Implementation and Construction. Jakarta: Yayasan Proklamasi, Centre for Strategic and International Studies. Moertopo, Ali 1973b Some Basic Thoughts on the Acceleration and Modernisation of 25 Years' Development. Jakarta: Yayasan Proklamasi, Centre for Strategic and International Studies. Moertopo, Ali 1978 Strategi Kebudayaan. Jakarta: Yayasan Proklamasi, Centre for Strategic and International Studies. Redfield, Robert, Ralph Linton, and Melville J. Herskovits 1936 Memorandum for the Study of Acculturation. American Anthropologist 38: 149-152. Sanderson, Stephen K. 1990 Social Evolutionism: A Critical History. Cambridge MA & Oxford UK: Blackwell. Schmidt, Wilhelm 1939 The Origin and Growth of Religion: Facts and Theories. H. J. Rose, trans. London: Methuen. Soebadio, Haryati 1985 Cultural policy in Indonesia (Studies and documents on cultural policies). Paris: UNESCO. Taylor, M. W. 1992 Men Versus the State: Herbert Spencer and Late Victorian Individualism. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Taylor, Paul M. 1994 The Nusantara concept of culture: Local traditions and national identity as expressed in Indonesia’s museums. In Fragile Traditions: Indonesian art in jeopardy, ed. Paul M. Taylor. Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press. Pp. 71-90. Toulmin, Stephen 1972 Human Understanding. Vol. I. Princeton: Princeton University Press. page 24 Voget, Fred W. 1975 A History of Ethnology. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. White, Leslie 1949 The Science of Culture: A Study of Man and Civilization. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Williams, Thomas Rhys 1972 Introduction to socialization: Human culture transmitted. Saint Louis: Mosby. The Writers Group 1978 What and Who in Beautiful Indonesia I. Jakarta: No publisher given. (Original Indonesian edition, 1975).