Challenge: How can a faculty of education model integrated

Challenge: How can a faculty of education model integrated curriculum for grades seven to twelve?

Harvey, Cher

Current research has shown that adolescents benefit from integrated studies (Hargreaves & Earl, 1990). Given philosophical and logistical barriers, how can a faculty of education model integrated curriculum for grades seven to twelve? This paper shares a case study of an Integrated

Day. It proposes six practical suggestions for successful implementation of integrated curriculum: a shared understanding, a model based on student interest, a team with energy and persistence, the commitment and involvement of everyone, a focus on what is manageable, and small steps with steady progress.

This paper shares a case study of how one Faculty of Education models integrated curriculum, assisting pre-service and classroom teachers in integrating curriculum for grades seven to twelve. Initial motivation was due to directives from the Ontario Ministry of Education and Training

(1995), as well as present theories of learning. Also, many of our students were experiencing integrated assignments in their practice teaching.

Caine and Caine (1991) state that the brain constantly looks for meaning in experience by searching for common patterns and connections.

The ability to see the links among different areas of learning will enable students to use the knowledge and skills developed in one field to learn in another and to relate their learning to real-life situations. Students need the ability to apply existing knowledge in new situations in order to function effectively in an environment of continuous change (Ministry of Education and Training of Ontario, 1995, p.10).

Integrated curriculum is an interdisciplinary perspective around a theme or issue. "Integrated learning helps students learn about relationships among ideas, events, and people" (Pogue, 1996). After much effort and time devoted to implementing curricular change, it was important for us as faculty to construct meaning out of our experience through writing. "When people can not construct new meaning, they will fall back into their old habits" (Drake, 1993, p.31).

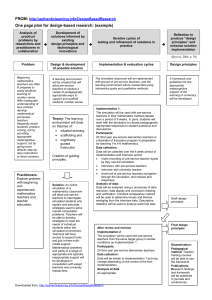

Theoretical Framework

The idea of integrating curriculum is not new. Var (1991) traces integrated curriculum back to Herbert Spencer in the 1800's, through to national curriculum reforms in the 1930's and 1940's, to the mainly supportive research in the 1980's. Teaching of subjects in compartments

has been the tradition, and traditions are difficult to change. We have been programmed by our educational backgrounds to turn on one subject for an hour, switch to another, and then turn to another. There seems to be a lag between research and practice. "Curriculum organization should reflect the way people learn, rather than the way knowledge is organized in disciplines" (Posner, 1995, p.161).

Research has shown that adolescents benefit from integrated studies

(Hargreaves & Earl, 1990). To meet the needs of adolescents, "We need to organize our teaching in ways that will help our kids begin to understand and participate in adult reality" (Atwell, 1987, p.26). Drake (1993, p.4) also concludes that if humans do learn by connection-making, it only makes sense to teach through connection. Current research (Fogarty, 1993;

Jacobs, 1989) outlines integrated curriculum methods for adolescents. It is difficult for pre-service teachers to implement this type of curriculum if they have not personally experienced it. "Responsiveness to change, interest in change, willingness to change are deeply rooted in teachers' own personal and professional development" (Hargreaves & Earl, 1990, p.14). Research supports an integrated curriculum, but only two research models of programs training pre-service teachers are documented (Sands

& Drake, 1996; McNaughton, Browne, Cooper, & Maeers, 1999). It is the intent of this paper to outline a process implemented successfully in one faculty of education.

Nipissing University: North Bay

Integrated curriculum, while not included in our program, was sometimes experienced by students in the practicum. The idea of modeling integration for preservice teachers was raised at the division level to ensure that all students could benefit from an introduction to the concept. The discussion process bogged down for a year and a half as faculty tried to find a mutually agreeable definition of "integration". Consensus was reached when one faculty member returning from a conference brought a video kit on curriculum integration models (Jacobs, 1993). Brown bag lunches for video viewing with related activities were organized. Heidi

Jacob's (1989) models of integration included the following five designs options: discipline based, parallel disciplines, multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary and integrated day. Our discussions, based on Jacob's theories, resulted in a collaborative effort to implement one of her models - The Inte-- grated Day.

The model was chosen because faculty was philosophically in agreement that it was important to present integrated curriculum to students. The

Integrated Day focuses on student interests and questions. All disciplines are placed on an equal basis. It is an introductory model that

was possible to implement within the timeframe, ensuring that all 150 students in the intermediate and senior divisions could participate.

Faculty did not have to reorganize their own courses, all could participate, and teaching load was accommodated. A committee of four volunteered to organize the implementation process.

Relevant Data

The entire population of students and full time faculty of Intermediate and Senior Divisions participated. We modeled the day in January due to a lengthy period on campus and timing led to investigating a "Pioneer

Winter". Students generated questions and ideas for exploration.

Suggestions were subdivided into areas of work, leisure, aesthetics, and environment, generating guiding questions for each. Faculty created four small teams to plan outcomes, strategies, resources, and evaluation. The four leaders were most interested in having a successful day, being originally the planning committee. Classrooms, space outside the building, and the cafeteria were utilized. Students were randomly divided into four groups giving them benefits of meeting and working with other pre-service teachers outside their subject specialization, or section.

Role of the Committee

The Integrated Day committee was composed of the chair of the intermediate division and three other enthusiastic faculty members, The four members met regularly to accomplish specific goals in a step by step approach.

The first three steps included: selecting an organizing design option; gathering student ideas and questions relating to our theme from professors of each discipline; and organizing student information into four broad headings: aesthetics, environment, work, and leisure. The committee developed the guiding questions: What did people appreciate and value in pioneer days? What were hardships of life confronting pioneers?

What type of work did pioneers experience? How did pioneers spend their leisure time? In step four faculty members worked in one workshop writing their station outcomes, resources, strategies and evaluation. For example, in the leisure workshop professors in French as a second language, language arts, and physical education drew from their own disciplines to create a workshop answering the question, "What did pioneers do in their leisure time?" At this point, the curriculum became integrated. In step five, faculty met as a whole ensuring everything was ready and checked the student booklet providing the theory for integration, steps in planning an Integrated Day, resources and bibliography.

The committee reporting to division meetings had responsibility of: being positive throughout the process, creating student groups, advertising,

providing a student information session, planning the introductory assembly, implementing the day, and reporting students' evaluations. to faculty. Initiated in 1993, refinements have been made annually based on feedback from students and faculty. Responses have always been very positive: "Fantastic", "Excellent", "Faculty were practicing what they were preaching", "Able to see how it works", and "Appreciate how much time and effort was put into this." "We became active learners, which is the best way to discover knowledge in context. It fostered cooperation and everyone had to participate".

Local teachers have also participated in the Integrated Day, enhancing communication with nearby boards. Pre-service teachers have been inspired to try an Integrated Day in their practice teaching sessions, with great success. Each year, the same committee members have willingly taken on the organizing task of Integration Day, as intermediate and senior faculty have felt that it should continue.

Research Method

Case study method was selected to share results of this program change in education for several reasons. "Knowledge of cases is precisely what defines the knowledge base in some fields" (Shulman, 1992, p.15). "In most case studies we are interested in change. Are things different now than they were before? Most of our measures of change are weak"(Stake, 1995, p.157). To draw conclusions from this curriculum change, willing participants of faculty and students were asked about their perceptions.

Using grounded theory (Glaser and Straus, 1967), a minimum of half a dozen participants with background and experience in the area studied were interviewed, and responses analyzed. The conclusions were an attempt at sharing "a set of social processes characterized by fragile and temporary bonds between persons who are attempting to share their lives and create from that sharing, a larger and wider understanding of the world" (Eisner

& Peshkin, 1990, p.287).

Participants were selected based on availability and willingness.

Interviews with eight faculty who had all participated in the Integrated

Day within the last three years, and five available graduates who participated in the January Integrated Day, were conducted at the end of the term. Faculty were asked to respond to the following questions:

How do you view your collaborative experience in the Integrated Day?

What reflections do you have on integrated curriculum after the Integrated

Day experience?

What are your perceptions of the potential for curriculum integration in the preservice program?

Student graduates were interviewed to collect data on how this experience was reflected in their thinking about integration and curriculum.

Students were asked to respond to the following questions:

What did you think about curriculum before you entered our program?

What reflections do you have on integrated curriculum after the Integrated

Day experience?

What are your perceptions of the potential for curriculum integration in the faculty of education and in the school system?

Participants in the study were interviewed at their convenience.

Responses were taped, transcribed and analyzed.

Research Findings

Initially student perception of curriculum at the beginning of the pre-service program was subject specific or disciplinary, and they were not familiar with the concept of integrated curriculum. "Curriculum is typical subjects, all separate" (Student S.). Responses on the evaluation sheet of the Integrated Day indicated that students could articulate the meaning of integrated curriculum, were willing to try in their first year of teaching and that all but a few students thoroughly enjoyed the day.

Reflection on the integration experi-- ence demonstrated that it provided the first step in awareness of integrated curriculum. "I never really understood it fully or internalized the idea until I lived it myself with your group last year" (Student N.) "This is only the beginning of helping the students develop the concept of integration" (Faculty P.). Reflection also indicated benefits to both faculty and students. "I really enjoyed the fact that all of the professors were involved. It showed collaborative effort and that they are really interested in our learning of integration"

(Student S.). "I felt, upon reflection, that until you have to articulate it, practice it, and model it to students, you may not realize that you do not know as much as you should know about integrated curriculum"(Faculty J.).

Further potential to integrated curriculum at the university and in the school system was recognized by both groups. "I would try to bring it into the classroom as much as possible" (Student L.). Faculty R. stated,

"Integration will become part of our program renewal as we look towards restructuring". Our research supports the comments on evaluation forms

completed by students and the importance of the Integrated Day experience to both students and faculty. "I enjoyed it, and it was lots of fun"

(Student N.). "Integrated Day was exciting! It was pleasurable working with other people who have different styles and interests. The validity of the day was in the students' excitement! (Faculty S.). Enjoyment of the day is not reason for so much effort, but enjoyment of learning is something that creates a better learning environment and thus aids in retention.

Difficulties

Description of this case study would not be complete without attention to difficulties encountered: staffing, timetabling, larger student numbers, and communication issues. Some faculty members were less convinced that this was a worthwhile endeavor. The philosophical discussion of the meaning of integrated curriculum must be repeated with new staff members to obtain necessary consensus and commitment. Despite success, the Integrated Day has never officially become part of program hours or workload. Extreme weather impacted negatively. Moving the day to October solved this but forced faculty to plan and implement integrated curriculum early in the program with students just beginning to develop initial concepts of curriculum. Doubled student numbers have made staffing, group sizing and locations almost impossible to manage.

Conclusion

Our experience with integrated curriculum has two significant implications for educators. First, Heidi Jacob's models (1989, 1993) may provide other faculties of education with the theories necessary to meet challenges of modeling integration with older students. The Integrated

Day model allowed all intermediate and senior pre-service students to experience integrated curriculum. Afterwards, they indicated a willingness to work collaboratively with other teachers modeling integration for adolescents. Second, although time is in short supply in facul-- ties given teaching, committee, practice teaching, and research responsibilities (Brochu, 1997, p3), planning the Integrated Day led to subsequent implementation of station based units and the parallel design model.

Analysis of the process and faculty reflection on the first steps in integrating curriculum indicate that our success was based on the following:

* Having a shared understanding

* Using a model based on student interest

* Having a team with energy and persistence

* Getting commitment and involvement of everyone

* Focusing on what is manageable

* Taking small steps, but making steady progress

Modeling integrated curriculum in a faculty of education can be achieved if professors overcome philosophical and logistical barriers with time, effort and optimism.

References

Atwell, N. (1987). In The Middle. Portsmouth, NH: Boyton/Cook

Publications.

Brochu, M. (1-997). The Role and Impact of Research in Smaller Ontario

Universities, report prepared for the Council of Ontario Universities.

Caine, R.N. and Caine, G. (1991). Making Connections: Teaching and the

Human Brain. Alexandria, Va: ASCD.

Drake, S. (1993). Planning Integrated Curriculum: The Call to Adventure.

Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Eisner, E. and Peshkin, A. (1990). Qualitative Inquiry in Education - The

Continuing Debate. New York: Teachers College Press.

Fogerty, R. (1991). The Mindful School: How to Integrate the Curricula.

Palatine, IL: Skylight Publishing.

Glaser, B.G. and Strauss, A.L. (1967). Discovery of Grounded Theory.

Chicago: Aldine Press.

Hargreaves, A. and Earl, L. (1990). Rights of Passages: A Review of

Selected Research About Schooling in the Transition Years, Toronto: OISE

Press.

Jacobs, H. (1989). Interdisciplinary Curriculum: Design and

Implementation. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and

Curriculum Development.

Jacobs, H. (1993). Video: Integrating the Curriculum. Alexandria, VA:

Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

McNaughton, K., Browne, N., Cooper, E., and Maeers, M. (1999). Moving

Toward Conceptual Integration. Action in Research. 21, 2. 80-89.

Ministry of Education and Training of Ontario. (1995). The Common

Curriculum. Toronto: Queen's Printer.

Pogue, L. (1996). Ages 12 Through 15: the Years of Transition. Toronto:

Ontario Public School Teachers' Federation.

Posner, G. (1995). Analyzing the Curriculum. New York: McGraw-Hill Inc.

Sands, D. and Drake, S. (1996). Exploring a Process for Delivering an

Interdisciplinary Preservice Elementary Education Curriculum: Teacher

Educators Practice What They Preach. Action in Research. 18, 3. 68-79.

Schulman, J. (1992). Case Study Methods in Teacher Education. New York:

Teachers College Press.

Stake, R. (1995). The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks, CF: Sage

Publication.

Var, G. (1991). Integrated Curriculum in Historical Perspective.

Educational Leadership.49, 14-15

DR. CHER HARVEY

DR. SANDRA REID

Faculty of Education

Nipissing University

100 College Drive

Box 5002

North Bay, ON PlB 8L7

Copyright Project Innovation Spring 2001

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights

Reserved