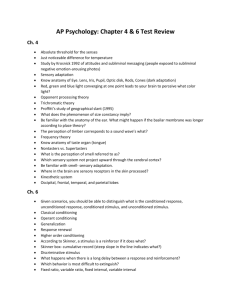

Chapter Review 8

Chapter 8: Learning

Classical Conditioning

Although learning by association had been discussed for centuries, it remained for Ivan Pavlov to capture the phenomenon in his classic experiments on conditioning.

Pavlov’s Experiments

Pavlov repeatedly presented a neutral stimulus (such as a tone) just before an unconditioned stimulus (UCS, food) that triggered an unconditioned response (UCR, salivation). After several repetitions, the tone alone (now the conditioned stimulus, CS) triggered a conditioned response (CR, salivation). Further experiments on acquisition revealed that classical conditioning was usually greatest when the CS was presented just before the

UCS, thus preparing the organism for what was coming. Other experiments explored the phenomena of acquisition, extinction, spontaneous recovery, generalization, and discrimination.

Pavlov’s work laid a foundation for John B. Watson’s emerging belief that psychology, to be an objective science, should study only overt behavior, without considering unobservable mental activity. Watson called this position behaviorism.

Extending Pavlov’s Understanding

The behaviorists’ optimism that learning principles would generalize from one response to another and from one species to another has been tempered. Conditioning principles, we now know, are cognitively influenced and biologically constrained. In classical conditioning, animals learn when to "expect" an unconditioned stimulus.

Moreover, animals are biologically predisposed to learn associations between, say, a peculiar taste and a drink that will make them sick, which they will then avoid. They don’t, however, learn to avoid a sickening drink announced by a noise.

Pavlov’s Legacy

Pavlov taught us that principles of learning apply across species that significant psychological phenomena can be studied objectively, and that conditioning principles have important practical applications.

Operant Conditioning

Through operant conditioning, organisms learn to produce behaviors that are followed by reinforcing stimuli and to suppress behaviors that are followed by punishing stimuli.

Skinner’s Experiments

Skinner showed that when placed in an operant chamber, rats or pigeons can be shaped to display successively closer approximations of a desired behavior. Researchers have also studied the effects of primary and secondary reinforcers, and of immediate and delayed reinforcers. Partial reinforcement schedules (fixed-ratio, variable-ratio, fixed-interval, and variable-interval) produce slower acquisition of the target behavior than does continuous reinforcement, but they also create more resistance to extinction. Punishment is most effective when it is strong, immediate, and consistent. However, it can have undesirable side effects.

Extending Skinner’s Understanding

Skinner’s emphasis on external control of behavior made him both influential and controversial. Many psychologists criticized Skinner (as they did Pavlov) for underestimating the importance of cognitive and biological constraints. For example, research on latent learning and motivation, both intrinsic and extrinsic, further indicates the importance of cognition in learning.

Skinner’s Legacy

Skinner’s ideas that operant principles should be used to influence people were extremely controversial. Critics felt he ignored personal freedoms and sought to control people. Today, his techniques are applied in schools, sports, workplaces, and homes. Shaping behavior by reinforcing successes is effective.

Learning by Observation

Another important type of learning, especially among humans, is what Albert Bandura and others call observational learning. In experiments, children tend to imitate what a model both does and says, whether the behavior is social or antisocial. Such experiments have stimulated research on social modeling in the home, within peer groups, and in the media. Children are especially likely to imitate those they perceive to be like them, successful, or admirable.