MODERN APPROACHES TO THE PATHOGENESIS OF UTERINE

advertisement

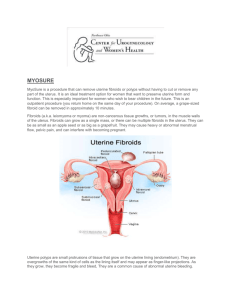

MODERN APPROACHES TO THE PATHOGENESIS OF UTERINE LEIOMYOMA, COMPLICATED WITH UTERINE BLEEDING (A LITERATURE REVIEW) M.M. Damirov N.V. Sklifosovsky Research Institute for Emergency Medicine of the Moscow Healthcare Department, Moscow, Russian Federation ABSTRACT Keywords: The article describes the basic pathogenetic mechanisms of uterine bleeding occurrence in patients with uterine leiomyoma (UL). The pathogenesis of this disease is difficult and multi-factorial. Significant changes in the architectonics of the uterine vasculature are noted. Modern approaches to management of patients with UL and uterine bleeding are discussed from a clinical point of view using conservative, minimally invasive and surgical methods of treatment. uterine leiomyoma, uterine bleeding, pathogenesis, treatment. EMU – extracellular matrix of the uterus UAE – uterine artery embolization UL – uterine leiomyoma THE URGENCY OF THE ISSUE Emergency assistance to women in conditions that threaten the health and life has a special place in the work of the obstetrician-gynecologist. One of the most common causes of women's need for medical care and hospitalization in the obstetrics and gynecology hospital is the genital tract bleeding. Uterine bleeding is one of the most important problems in urgent gynecology [1, 2]. Bleeding from the genital tract, which cannot be classified as a normal menstruation, is a symptom of dysfunctional disorders, proliferative gynecological diseases (uterine leiomyoma – UL, adenomyosis, endometrial hyperplasia) as well as oncologic and extragenital diseases [3-6]. The bleeding may be profuse, excessive, and insignificant. It is noteworthy that the amount of bleeding itself is one of the most important factors determining the need for emergency medical care. Uterine bleeding is the major symptom of UL, and its intensity and nature often determine the severity of the patient’s condition and procedures providing emergency medical care. UL is diagnosed in 10-52% of patients holding second place in the structure of gynecological morbidity [7, 8]. There has been a clear trend towards higher incidence of the disease while "rejuvenation" of patients recently. Thus, sonographic study often reveals UL in 20-30 y.o. patients [9, 10]. The selection of the optimal management for patients with UL is challenging due to the fact that this type of decease is rarely diagnosed in isolation, and often combined with different types of proliferative diseases of the uterus. So, if there is uterine bleeding, the incidence of UL combinations and endometrial hyperplastic processes is 52-67% [3, 11]. The most common method to stop bleeding in UL is total or subtotal hysterectomy. Patients with this type of disease undergo more than 50% of surgeries performed in gynecological practice [6, 12]. It is understood that hysterectomy irreversibly leads to infertility of women. Therefore, the search for effective methods to save organs in uterine bleeding caused by UL has been running on. The purpose of this review is to examine the mechanisms of uterine bleeding in patients with UL and analyze modern methods of hemostasis in emergency medical care. DISCUSSION Currently, there are several theories to explain the causes of uterine bleeding in patients with UL. One of the most common position is that the growth of the myomatous node increases internal surface area of the uterus, and therefore the endometrial surface area grows, which in turn increases the volume of lost blood [4, 13, 14]. Factors contributing to the increase in blood loss also include: violation of the contractile ability of the myometrium, defective tissue of the myometrium and blood vessels located in the muscular layer; functional and structural changes of the endometrium and its increased fibrinolytic activity [7, 11]. The question of the mechanical labor of myomatous nodes in uterine contraction is extremely controversial, as there is no evident link between the size and location of nodes, as well as the nature and duration of uterine bleeding [13, 15]. So, electrohysterographic studies performed in patients with UL showed no correlation between the feature of uterine contraction and the origin and duration of uterine bleeding [14]. Of course, in some cases, combination of the above factors may be observed, which leads to the development of bleeding ultimately. However, this assumption is based on empirical experience due to the lack of a statistically significant correlation between the size, localization, morphological type of myomatous nodes and the origin, volume and duration menometrorrhagias. Theory of "vascular origin" of uterine bleeding has a large number of supporters [7]. It should be noted that in UL significant changes in the architectonics of the uterine vasculature are observed such as enlargement of main blood vessels caliber – the uterine arteries and veins. Also, different types of blood supply are diagnosed in different localizations of tumor vessels which are linear or tortuous [7]. The study of vascular structures revealed that the process of myocytes hypertrophy during the growth of UL is accompanied by abnormal development of the capillary network. The main feature of the myometrium in the development of UL is excessive activation of cambium elements of connecting-vascular system of the myometrium, leading to excess production of plastic material for the growth of blood vessels and the formation of proliferative myogenic cells [6]. At the same time, an increase in the volume and area of the myocyte nucleus, as well as of the DNA, indicates a high mitotic activity of the nucleus. If the location of the tumor is intramuscular, vasculature of the uterus is developed to the greatest extent, because the blood supply to the nodes is carried out with the help of a large number of anastomoses. Blood supply to submucosal nodes of UL often occurs through one or two larger vessels arising from the ascending branch of the uterine artery, and a well-developed network of smaller vessels [6, 7, 12, 14]. The subserous nodes are least supplied. It is shown that arterial vessels are dilated, and deprived of the ability to contract in the UL tissue, so when the tumor is located directly beneath the endometrium (uterine leiomyoma with centripatal growth), there is often an uterine bleeding [7]. In the myomatous uterus, production and distribution of vasoactive agents and growth factors are impaired that influence the angiogenesis that results in abnormal structure and dysfunction of the vascular wall [13]. In patients with UL, not only violation of the structure of blood vessels is particularly important, but also violation of the venous outflow due to the tumor lesions [16]. Venous network is largely changed in patients with UL: venules are dramatically dilated, their lumen is constantly open; merging with each other, they form the so-called venous lakes [17]. In the myometrium containing myomatous nodes, the amount of venous plexuses is increased, especially on the periphery of lesions [9, 18]. Subsequently, a light microscope in patients with UL identified ectasia of venules in the myometrium and endometrium [14]. It should be noted that changes in venous flow were most significant in the layer of the uterus, where the tumor develops [7]. However, it was also noted that the venous vessels that were the part of the myoma node capsule, significantly differed from the structure of the vessels of uterric layer where the tumor develops in their shape, diameter and orientation. The outflow of venous blood from subserous and submucosal nodes is the result of merging of several smaller vessels going to the base of the tumor, to nearby vessels of the capsule and efferent veins of the uterus, and from interstitial nodes – going along vessels in the radial direction of the tumor in the uterus to the veins around the entire node by numerous, but smaller veins [16]. The dilatation of myometrium and endometrium veins is directly caused by compression of uterine vessels with leiomyoma nodes to some extent, resulting in impaired venous outflow and increased blood filling in the body. This gave rise to the theory that explains developing ectasia of venules by mechanical compression of the veins with myomatous nodes [19]. However, it was shown that the severity of vascular changes and the tendency to occurrence of uterine bleeding were associated with the location and size of the myomatous nodes. With its small size (up to 1 cm), there are no changes in the vasculature, whereas they are significant in large tumors [7]. The resulting ectasia of venules leads to the failure of the primary platelet hemostasis by increasing the diameter of the lumen of blood vessels, which is clinically manifested by menometrorrhagia. It is shown that, along with ectasia of venules, arteries, veins and uterine extracellular matrix (EMU) are changing [12, 20]. There is strong evidence showing the significant role of EMU in development and cell differentiation of normal and pathological changes of the myometrium. EMU is supramolecular complex forming extracellular environment, which affects differentiation, proliferation and attachment of cells [14]. EMU includes interstitial collagen, proteoglycans, fibronectin and some other large molecular compounds. It is noted that not only mechanical compression, but various vasoactive local dysregulation of growth factors and their receptors (as leiomyoma and myometrium around) showing a violation of their synthesis, are the major reasons for vascular disorders [17]. It is possible that the contractile ability of the myometrium changes as a result of frequently occurring inflammatory diseases of the uterus, which may also be one of the reasons leading to the occurrence of uterine bleeding. I should be noted that in patients with UL endometrial hyperplasia is often diagnosed, which may also lead to the occurrence of uterine bleeding [7, 8, 11]. Of course, in some cases, combination of the above factors may be observed, which, ultimately, leads to the development of excessive uterine bleeding. To understand the mechanism of ejection of the endometrium in normal and in various pathological conditions, as well as features of hemostasis in the uterus, it is necessary to describe the endometrium in various phases of the menstrual cycle. Complete rejection of the functional layer usually finishes on the 3rd day of the cycle. Menstruation comes from the proximal vessels supplying the functional layer of the endometrium [21]. After the rejection of the functional layer, endometrium is a thin and a thick tissue, and the reduction of its thickness occurs not only due to the loss of the functional layer (up to 2/3 of the height) but also due to the reduction of reticular elements of the tissue matrix [22]. If the rejection of the endometrium layer occurs quickly, the duration of bleeding is most often insignificant. When desquamation of the endometrium is asynchronous and stretched in time, the duration and intensity of uterine bleeding increases. Endometrial reparative process begins simultaneously with the rejection of its functional layer, and on day 1-5 of the cycle the repair may occur due amitotic cell division [23]. With the 5th day of the menstrual cycle, estrogen-dependent proliferation of endometrium begins. It is important that the endometrial vascular structure is the continuation of myometrial vessels. Endometrial blood supply is carried out from two systems of arterioles: straight and spiral. Vascularization of the basal layer of the endometrium is performed due to straight arteries, whereas the spiral arteries supply blood to the functional layer. Vessels of endometrial functional layer have a higher sensitivity to sex steroids, while vessels of the basal layer are devoid of this property and do not undergo cyclic transformations. Straight arterioles perform normal nutritional function, whereas the spiral arterioles, moving up from basal to functional structures play an important role in the physiological and histological endometrial cycle [16]. Arcuate arteries of myometrium have radial branches (basal arteries), which begin to twist and form the spiral arteries, penetrating the endometrium. Spiral arteries, unlike the basal ones, are sensitive to changes of estrogen and progesterone, which ensures the process of desquamation of the endometrial functional layer due to vasoconstriction leading to ischemia and necrosis. Spiral artery remaining in the endometrium, which underwent regression do not always fully drain and can serve as a source of bleeding during the next menstrual period, causing their duration, and profusion [21, 24]. After completion of desquamation, regeneration of basal arteries begins. On a microscopic level, the process is divided into four steps: a) destruction of the basal membrane; b) migration of endothelial cells; c) proliferation of endothelial cells; g) formation of the capillary. During degradation of the basal membrane specific enzymes (stromelysin, collagenase, etc.) EMU destroy elements. Then, endothelial cells migrate into the end of the vessel, which is facilitated by an environment rich in collagen type I and III, and a stimulating effect of bFGF [14]. Further proliferation of endothelial cells and blood vessels lumen formation also depend on EMU components. The myometrium is a huge reservoir of various paracrine and endocrine factors regulating the function of the endometrium. This relationship provides a juxtaposition of these two tissues, as well as the direct blood circulation from the myometrium into the endometrium. Growth factors and their receptors, stimulating angiogenesis and reducing the vascular tone, are overexpressed in myomatous uterus and are also responsible for the occurrence of uterine leiomyoma-associated bleeding. On the other hand, the decrease in the expression of growth factors, inhibiting angiogenesis or vasoconstriction in leiomyoma may initiate uterine hemorrhage [14]. Thus, in patients with UL various growth factors can influence vascular tissue, stimulate its proliferation and change the caliber, causing uterine bleeding due to violation of their synthesis, receptors expression and degradation. Mechanism of the vaginal bleeding may differ depending on its source. The duration of uterine bleeding is defined by coordinated functioning of vascular, hemostatic, cell and tissue factors. It is known that the bleeding from the tissue of the cervix or vagina terminates only through coagulation and vascular-platelet activity of hemostasis [22]. However, the tissue of the uterine body has additional features which may stop bleeding. It has been shown that reduction in the myometrium, which causes narrowing of the arteries, going almost perpendicular to the surface of the uterus, as well as muscle spasm of the elements of the vascular wall of arteries themselves, are among the leading factors of hemostasis [7]. For this reason, violation of architectonics of myometrium and vascular bed cause bleeding on the one hand, but prevents it from termination as well [16]. If the cause of menorrhagia in patients with UL is associated endometrial hyperplasia, the treatment should eliminate this concomitant impairment. Upon admission of patients with UL in reproductive, peri- and / or menopausal stage, with the clinical picture of menorrhagia and/or metrorrhagia, diagnosed by ultrasound endometrial hyperplasia and UL, the management patient is defined by his or her general condition, the intensity of blood discharge, data of clinical and laboratory diagnosis (results of clinical, biochemical blood tests, coagulation and others) and the results of gynecological and ultrasound examinations [3, 8]. Hormonal hemostasis is ineffective for uterine bleeding in UL [7, 12]. Accordingly, in the case of medium severity the patient (mild severe anemia, scant uterine bleeding and small size of the uterus) undergo separate curettage of cervical canal and mucosa of the uterine body (under hysteroscopic control) with a hemostatic, as well as therapeutic and diagnostic purpose, followed by histological examination of the scrape [6, 11]. This scraping is performed in the course of the hemostatic and infusion-transfusion therapy. Further management of patients is determined by the results of clinical data, the size of the uterus, the location and size of myomatous nodes, the presence of diagnosed co-proliferative diseases, features of postoperative period and histological examination of the endometrial scraping [3, 8, 11]. In some cases, surgical ligation of internal iliac arteries is recommended to stop uterine bleeding [25]. At the same time, it has been found by angiography that bilateral vascular ligation does not completely stop the blood flow in the internal iliac artery distally to the site of ligation, and its redistribution occurs by opening collaterals. This reliable hemostasis is not achieved due to the rapid development of collateral circulation, and in 10% of cases the bleeding may be renewed in the immediate postoperative period [25]. Development and introduction of endoscopic techniques into clinical practice have created new approaches in the treatment of uterine bleeding in patients with UL. Mini-invasive technologies saving organs such as hysterectomoscopic operations have been performed recently to remove submucous myomatous nodes and prevent uterine bleeding caused by them. However, these transactions may not be possible to be performed by emergency medical services in unexamined patients with UL with the clinical picture of uterine bleeding. Myolysis (artificial purulation inside the tumor with cauterization) is also used in the treatment of UL. A new step in the development of this method was made due to introduction of operative gynecology laparoscopic approach using various sources of energy: high-energy lasers, bipolar coagulation, cryotherapy, high-frequency ultrasound [6, 12]. However, this method has not found application in clinical practice for termination of uterine bleeding in patients with UL. Clinical experience shows that one of the main treatments for uterine bleeding caused by UL is still the surgery. The concept of functional surgery in patients with UL has become recognized recently. In this regard, it is extremely urgent to develop new treatments for patients with UL in the provision of emergency medical care, which stop uterine bleeding and preserve the reproductive function of women. The interest in the use endovascular methods of treating patients with different diseases in clinical practice has increased recently. With the development of endovascular techniques such mini-invasive treatment for UL as uterine arteries embolization (UAE) became widespread [14, 26]. By this time, over 100, 000 endovascular embolizations for various gynecological diseases have been performed [27]. In the literature, the issue of reducing the size of the uterus and myomatous nodes in patients with UL to save the woman's reproductive plans and reducing the clinical manifestations of the disease has been mainly discussed [3]. However, this endovascular technology is not widely used in the treatment of patients with UL complicated with uterine bleeding. Thus, the development and introduction of modern approaches to hemostasis in patients with UL with clinical picture of uterine bleeding are relevant in providing emergency medical care. Further study of the pathogenesis of this disease allows optimizing the choice of methods of treatment for patients with UL complicated with the uterine bleeding. ЛИТЕРАТУРА 1. Лихачев В.К. Практическая гинекология с неотложными состояниями: руководство для врачей. – М.: МИА, 2013. – 840 с. 2. Цвелев Ю.В., Беженарь В.Ф., Берлев И.В. Ургентная гинекология (практическое руководство для врачей). – СПб: ООО «Изд-во ФОЛИАНТ», 2004. – 384 с. 3. Гинекология: национальное руководство / под ред. В.И. Кулакова, И.Б. Манухина, Г.М. Савельевой. – М.: ГЭОТАРМедиа, 2011. – 1088 с. 4. Гинекология от пубертата до постменопаузы: практ. Руководство для врачей / под ред. Э.К. Айламазяна. – 3-е изд., доп. – М.: МЕДпресс-информ, 2007. – 500 с. 5. Дамиров М.М., Олейникова О.Н., Майорова О.В. Генитальный эндометриоз: взгляд практикующего врача. – М.: БИНОМ, 2013. – 152 с. 6. Стрижаков А.Н., Давыдов А.И., Пашков В.М. Доброкачественные заболевания матки. – М.: ГЭОТАР-Медиа, 2011. – 288 с. 7. Вихляева Е.М. Руководство по диагностике и лечению лейомиомы матки. – М.: МЕДпресс-информ, 2004. – 400 с. 8. Миома матки: диагностика, лечение и реабилитация. Клинические рекомендации по ведению больных (проект) / под ред. Л.В. Адамян. – Москва, 2014. – 94 с. 9. Озерская И.А. Эхография в гинекологии. – 2-е изд., перераб. И дополн. – М.: Издательский дом Видар. – М. , 2013. – 564 с. 10. Kurjak S., Kupesic А. An atlas of transvaginal color Doppler. – 2nd ed. – N-York, London: The Parthenon publishing group, 2000. – 472 p. 11. Дамиров М.М. Современные подходы к тактике ведения больных с лейомиомой матки: пособие для врачей. – М., 2014. – 91 с. 12. Гинекология: руководство для врачей / под ред. В.Н. Серова, Е.Ф. Кира. – М.: Литтерра, 2008. – 856 с. 13. Сидорова И.С. Миома матки (современные проблемы этиологии, патогенеза, диагностики и лечения. – М.: МИА, 2003. – 256 с. 14. Тихомиров А.Л., Лубнин Б.М. Миома матки. – М.: МИА, 2006. – 176 с. 15. Baschinsky D.Y., Isa A., Niemann Т.Н., et al. Diffuse leiomyomatosis of the uterus: a case report with clonality analysis // Hum. Pathol. – 2000. – Vol. 31, N. 11. – P. 1429–1432. 16. Кондриков Н.И. Патология матки. – М.: Практическая медицина, 2008. – 334 с. 17. Гридасова В.Е. Роль сосудистых факторов в патогенезе миомы матки: автореф. Дис. … канд. Мед. Наук. – М., 2003. – 23 с. 18. Кох Л.И., Радионченко А.А. Особенности строения миометрия при лейомиоме матки // Акуш. И гинекол. – 1988. – № 5. – С. 8–10. 19. West C.P., Lumsden M.A. Fibroids and menorrhagia // Baillieres Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. – 1989. – Vol. 3, N. 2. – P. 357–374. 20. Stewart E.A., Nowak R.A. Leiomyoma-related bleeding: a classic hypothesis updated for the molecular era // Hum. Reprod. Update. – 1996. – Vol. 2, N. 4. – P. 295–306. 21. Хмельницкий О.К. Цитологическая и гистологическая диагностика заболеваний шейки и тела матки: руководство. – СПб.: Сотис, 2000. – 332 с. 22. Подзолкова Н.М., Глазкова О.Л. Симптом. Синдром. Диагноз. Дифференциальная диагностика в гинекологии. – М.: ГЭОТАР–Медиа, 2014. – 772 с. 23. Speroff L., Glass R.H., Kase N.G. Clinical 4ynaecologic endocrinology and infertility. – Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1993. – 668 p. 24. Серов В.Н., Звенигордский И.Н. Диагностика гинекологических заболеваний с курсом патологической анатомии. – М.: БИНОМ. Лаборатория знаний, 2003. – 139 с. 25. Курцер М.А., Бреслав М.А. Значение перевязки внутренних подвздошных артерий в лечении массивных акушерских кровотечений // Акушерство и гинекология. – 2008. – № 6. – С. 18–22. 26. Эмболизация маточных артерий в практике акушера-гинеколога / под ред. Ю.Э. Доброхотовой, С.А. Капранова. – М.: Литтерра, 2011. – 96 с. 27. Эмболизация маточных артерий в лечении миомы матки / Капранов С.А., Бреусенко В.Г., Доброхотова Ю.Э. и др. // Руководство по рентгеноэндоваскулярной хирургии сердца и сосудов: в 3-х т. / под ред. Л.А. Бокерия, Б.Г. Алекяна. – М.: НЦССХ им. А.Н. Бакулева, 2013. – Т.1. Рентгеноэндоваскулярная хирургия заболеваний магистральных сосудов. – Гл. 37. – С. 542–597. Article received on 26 January, 2015 For correspondence: Prof. Mikhail Mikhaylovich Damirov Head of the Scientific Department of Acute Gynecological Diseases, N.V. Sklifosovsky Research Institute for Emergency Medicine of the Moscow Healthcare Department, Moscow, Russian Federation e-mail: damirov@inbox.ru