Dante reading

advertisement

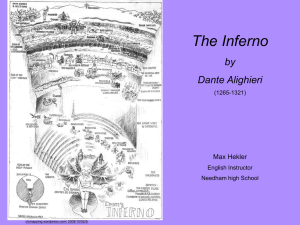

Background on Dante and Interpretations of The Divine Comedy Dante Alighieri, 1265-1321, Italian poet, author of The Divine Comedy. In 1290, after the death of his exalted Beatrice (Beatrice Portinari, 1266-90), he plunged into the study of philosophy and Provençal poetry. Politically active in Florence from 1295, he was banished in 1302 and became a citizen of all Italy, dying in Ravenna. There was a decree of death if he was found within the city of Florence, so he roamed the rest of Italy for the rest of his life looking to be a house guest, writing The Divine Comedy and prohibited from taking part in politics. The Divine Comedy, a vernacular poem, is the tale of the poet's journey through Hell and Purgatory (guided by Vergil) and through Heaven (guided by Beatrice, a woman he passionately, but platonically loved [no touching, no marriage], to whom the poem is written as a memorial.) Written in a complex pentameter form, it is a magnificent synthesis of the medieval outlook, picturing a changeless universe ordered by God. He was the first to showcase literature in the vernacular—meaning, he wrote in the language of the common people, and showed that art and literature could be accessible and lofty at the same time. About Inferno: Dante was a great fan of the Roman poet Virgil, and he based his idea of the cosmography of hell on Virgil’s pre-Christian description of the underworld as is found in Book 6 of Aeneid. In Inferno, Virgil resides in the top layer of Hell known as Limbo (having been unlucky enough to have been born before Christ and therefore not aware of Christianity). He is Dante’s guide. As they descend lower and lower into the depths of Hell, the punishments inflicted on Dante’s political enemies become more horrific. Hell is organized into a series of circles, one on top of the other, narrowing as it gets deeper and deeper, until the travelers reach the centermost, deepest part. The deepest part of hell (called the “Malebolge”) is located directly beneath Jerusalem. According to Dante, when Satan fell, he pierced the earth’s crust at that point and became embedded in the Malebolge. Some of the souls interrogated by Dante are talkative, and some are ashamed and tell him to leave them alone. Some, indeed, Dante has a sneaking admiration for, while some recognize that Dante’s physical body has substance and inquire of him why he has reached the afterlife before his time. Basic Summary: At the age of thirty-five, on the night of Good Friday in the year 1300, Dante finds himself lost in a dark wood and full of fear. He sees a sun-drenched mountain in the distance, and he tries to climb it, but three beasts, a leopard, a lion, and a she-wolf, stand in his way. Dante is forced to return to the forest where he meets the spirit of Virgil, who promises to lead him on a journey through Hell so that he may be able to enter Paradise. Dante agrees to the journey and follows Virgil through the gates of Hell. The two poets enter the vestibule of Hell where the souls of the uncommitted are tormented by biting insects and damned to chase a blank banner around for eternity. The poets reach the banks of the river Acheron where souls await passage into Hell proper. The ferryman, Charon, reluctantly agrees to take the poets across the river to Limbo, the first circle of Hell, where Virgil permanently resides. In Limbo, the poets stop to speak with other great poets, Homer, Ovid, Horace, and Lucan, and then enter a great citadel where philosophers reside. Background on Dante and Interpretations of The Divine Comedy Dante and Virgil enter Hell proper, the second circle, where monster, Minos, sits in judgment of all of the damned, and sends them to the proper circle according to their sin. Here, Dante meets Paolo and Francesca, the two unfaithful lovers buffeted about in a windy storm. The poets move on to the third circle, the Gluttons, who are guarded by the monster Cerberus. These sinners spend eternity wallowing in mud and mire, and here Dante recognizes a Florentine, Ciacco, who gives Dante the first of many negative prophesies about him and Florence. Upon entering the fourth circle, Dante and Virgil encounter the Hoarders and the Wasters, who spend eternity rolling giant boulders at one another. They move to the fifth circle, the marsh comprising the river Styx, where Dante is accosted by a Florentine, Filippo Argenti; he is amongst the Wrathful that fight and battle one another in the mire of the Styx. The city of Dis begins Circle VI, the realm of the violent. The poets enter and find themselves in Circle VI, realm of the Heretics, who reside among the thousands in burning tombs. Dante stops to speak with two sinners, Farinata degli Uberti, Dante's Ghibelline enemy, and Cavalcante dei Cavalcanti, father of Dante's poet friend, Guido. The poets then begin descending through a deep valley. Here, they meet the Minotaur and see a river of boiling blood, the Phlegethon, where those violent against their neighbors, tyrants, and war-makers reside, each in a depth according to their sin. Virgil arranges for the Centaur, Nessus, to take them across the river into the second round of circle seven, the Suicides. Here Dante speaks with the soul of Pier delle Vigne and learns his sad tale. In the third round of Circle VII, a desert wasteland awash in a rain of burning snowflakes, Dante recognizes and speaks with Capaneus, a famous blasphemer. He also speaks to his beloved advisor and scholar, Brunetto Latini. This is the round held for the Blasphemers, Sodomites, and the Usurers. The poets then enter Circle VIII, which contains ten chasms, or ditches. The first chasm houses the Panderers and the Seducers who spend eternity lashed by whips. The second chasm houses the Flatterers, who reside in a channel of excrement. The third chasm houses the Simonists, who are plunged upside-down in baptismal fonts with the soles of their feet on fire. Dante speaks with Pope Nicholas, who mistakes him for Pope Boniface. In the fourth chasm, Dante sees the Fortune Tellers and Diviners, who spend eternity with their heads on backwards and their eyes clouded by tears. At the fifth chasm, the poets see the sinners of Graft plunged deeply into a river of boiling pitch and slashed at by demons. At the sixth chasm, the poets encounter the Hypocrites, mainly religious men damned to walk endlessly in a circle wearing glittering leaden robes. The chief sinner here, Caiaphas, is crucified on the ground, and all of the other sinners must step on him to pass. Two Jovial friars tell the poets the way to the seventh ditch, where the Thieves have their hands cut off and spend eternity among vipers that transform them into serpents by biting them. They, in turn, must bite another sinner to take back a human form. At the eighth chasm Dante sees many flames that conceal the souls of the Evil Counselors. Dante speaks to Ulysses, who gives him an account of his death. Background on Dante and Interpretations of The Divine Comedy At the ninth chasm, the poets see a mass of horribly mutilated bodies. They were the sowers of discord, such as Mahomet. They are walking in a circle. By the time they come around the circle, their wounds knit, only to be opened again and again. They arrive at the tenth chasm the Falsifiers. Here they see the sinners afflicted with terrible plagues, some unable to move, some picking scabs off of one another. They arrive at the ninth circle. It is comprised of a giant frozen lake, Cocytus, in which the sinners are stuck. Dante believes that he sees towers in the distance, which turn out to be the Giants. One of the Giants, Antaeus, takes the poets on his palm and gently places them at the bottom of the well. Circle IX is composed of four rounds, each housing sinners, according to the severity of their sin. In the first round, Caina, the sinners are frozen up to their necks in ice. In the second round, Antenora, the sinners are frozen closer to their heads. Here, Dante accidentally kicks a traitor in the head, and when the traitor will not tell him his name, Dante treats him savagely. Dante hears the terrible story of Count Ugolino, who is gnawing the head and neck of Archbishop Ruggieri, due to Ruggieri's treacherous treatment of him in the upper world. In the third round, Ptolomea, where the Traitors to Guests reside, Dante speaks with a soul who begs him to take the ice visors, formed from tears, out of his eyes. Dante promises to do so, but after hearing his story refuses. The fourth round of Circle IX, and the very final pit of Hell, Judecca, houses the Traitors to Their Masters, who are completely covered and fixed in the ice, and Satan, who is fixed waist deep in the ice and has three heads, each of which is chewing a traitor: Judas, Brutus, and Cassius. The poets climb Satan's side, passing the center of gravity, and find themselves at the edge of the river Lethe, ready to make the long journey to the upper world. They enter the upper world just before dawn on Easter Sunday, and they see the stars overhead. Themes of Dante’s Inferno Themes are the fundamental and often universal ideas explored in a literary work. 1. The Perfection of God’s Justice Dante creates an imaginative correspondence between a soul’s sin on Earth and the punishment he or she receives in Hell. The Sullen choke on mud, the Wrathful attack one another, the Gluttonous are forced to eat excrement, and so on. This simple idea provides many of Inferno’s moments of spectacular imagery and symbolic power, but also serves to illuminate one of Dante’s major themes: the perfection of God’s justice. The inscription over the gates of Hell in Canto III explicitly states that God was moved to create Hell by JUSTICE (III.7). Hell exists to punish sin, and the suitability of Hell’s specific punishments testify to the divine perfection that all sin violates. Background on Dante and Interpretations of The Divine Comedy This notion of the suitability of God’s punishments figures significantly in Dante’s larger moral messages and structures Dante’s Hell. To modern readers, the torments Dante and Virgil behold may seem shockingly harsh: homosexuals must endure an eternity of walking on hot sand; those who charge interest on loans sit beneath a rain of fire. However, when we view the poem as a whole, it becomes clear that the guiding principle of these punishments is one of balance. Sinners suffer punishment to a degree befitting the gravity of their sin, in a manner matching that sin’s nature. God’s justice emerges as rigidly objective, mechanical, and impersonal; there are no extenuating circumstances in Hell, and punishment becomes a matter of nearly scientific formula. Early in Inferno, Dante builds a great deal of tension between the objective impersonality of God’s justice and the character Dante’s human sympathy for the souls that he sees around him. As the story progresses, however, the character becomes less and less inclined toward pity—sinners receive punishment in perfect proportion to their sin; to pity their suffering is to demonstrate a lack of understanding. 2. Man’s relationship with God In The Inferno, God is not presented as all-loving and benevolent. Rather, the creator is curiously absent; he is only mentioned as either a consequence of sin or as injured by the sinner. Otherwise, the poem deals exclusively with hell and sinners. Likewise, there is no mercy, and no interference from God of any kind. 3. Sin and Punishment It is primarily in the description of the punishment for individual sin that the Inferno has any logic. The sin “fits” the crime. Specifically, the punishment repays the sinner in the exact way the sinner harmed himself and/or others. 4. Political revenge Dante uses Inferno as a vehicle to assassinate the characters of—and thereby get revenge on— his political enemies. The poem is written in the vernacular, so the common, ill-educated man might read it. The common man is far more likely to accept the poem as gospel truth. 5. Evil as the Contradiction of God’s Will In many ways, Dante’s Inferno can be seen as a kind of imaginative taxonomy of human evil, the various types of which Dante classifies, isolates, explores, and judges. It declares that evil is evil simply because it contradicts God’s will, and God’s will does not need further justification. Dante’s exploration of evil probes neither the causes of evil, nor the psychology of evil, nor the earthly consequences of bad behavior. Inferno is not a philosophical text; its intention is not to think critically about evil but rather to teach and reinforce the relevant Christian doctrines.