Expository & Persuasive Writing Guide: Models & Techniques

advertisement

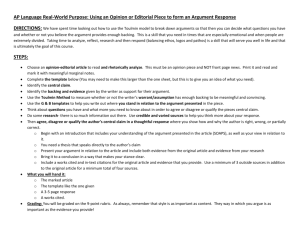

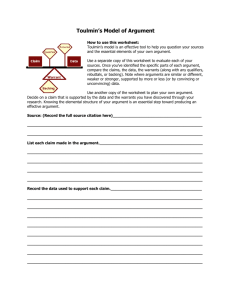

Expository and Persuasive Writing What is Expository Writing? Exposition is a type of oral or written discourse that is used to explain, describe, give information or inform. The creator of an expository text cannot assume that the reader or listener has prior knowledge or prior understanding of the topic that is being discussed. One important point to keep in mind for the author is to try to use words that clearly show what they are talking about rather then blatantly telling the reader what is being discussed (show, don’t tell). Since clarity requires strong organization, one of the most important mechanisms that can be used to improve our skills in exposition is to provide directions to improve the organization of the text. So, expository writing directs paragraphs into specific directions, most specifically, to explain the writer’s position on any given subject (prompts). Kinds of Exposition (Writing 1) Narrative Interspersion: A pattern or a sub-pattern imbedded in other patterns in which the speaker or writer intersperses a narrative within the expository text for specific purposes, including to clarify, or elaborate on a point or to link the subject matter to a personal experience. Recursion: When the speaker discusses a topic, then restates it using different words or symbolism. It is used to drive home a point and to give special emphasis to the text. Description: The author describes a topic by listing characteristics, features, and examples…”for example, characteristics are…” Sequence: The author lists items or events in numerical or chronological order…”first, second, third; next; then; finally” Compare and contrast: The author explains how two or more things are alike and/or how they are different…”different; in contrast; alike; same as; on the other hand, similarly” Cause and Effect: The author lists one or more causes and the resulting effect or effects…”reasons why; if...then; as a result; therefore; because; for example” Problem and Solution: The author states a problem and lists one or more solutions for the problem. A variation of this pattern is the question- and-answer format in which the author poses a question and then answers it….”problem is; dilemma is; puzzle is solved; the question is ... the answer /solution is…” Circumlocution: Depicts a pattern in which the speaker discusses a topic, then diverts to discuss a related but different topic. Often used to connect seemingly different ideas/topics. Analogy: comparing two different subjects or ideas a similarity between like features of two things, on which a comparison may be based: the analogy between the heart and a pump Process Analysis: carefully examining all parts of a whole, usually done in steps Division and Classification: arranges people, objects, or ideas with shared characteristics into classes or groups. Definition: defines a word, term, or concept in depth. Does NOT rely on the dictionary. Meaning comes from multiperspectives (from many different levels, not just the obvious). Negation: explaining what something is not, to explain what something is. Description: relies on their nominal stature; it is more important to use imagery and metaphorical language than scientific data. Kinds of Argument (Writing10) The Toulmin Model Arguing that absolutism lacks practical value Stephen Toulmin (1922-2009) aimed to develop a different type of argument, called practical arguments (also known as substantial arguments). In contrast to absolutists’ theoretical arguments, Toulmin’s practical argument is intended to focus on the justificatory function of argumentation, as opposed to the inferential function of theoretical arguments. Whereas theoretical arguments make inferences based on a set of principles to arrive at a claim, practical arguments first find a claim of interest, and then provide justification for it. Toulmin believed that reasoning is less an activity of inference, involving the discovering of new ideas, and more a process of testing and sifting already existing ideas—an act achievable through the process of justification. Toulmin believed that for a good argument to succeed, it needs to provide good justification for a claim. This mode is defined as…. “a good argument can succeed in providing good justification to a claim, which will stand up to criticism and earn a favorable verdict”. The Toulmin method uses qualifiers “sometimes, often, presumably, unless, almost” etc. to acknowledge the differences and complications of life. In The Uses of Argument (1958), Toulmin proposes a layout containing six interrelated components for analyzing arguments. They are: Claim A conclusion whose merit must be established. For example, if a writer tries to convince their readers of their interpretations of a text, the claim might be “Reality television is hardly an accurate representation of reality, since every show is heavily produced, has several writers on staff, and whose content is edited to suit the story producers and writers have in mind.” Students often make several claims but do not consistently support them. The central claim is also the thesis. Evidence (Data) A fact one appeals to as a foundation for the claim in the form of quotes, visuals, showdon’t tell, various modes of expressing an idea, including: definition, compare and contrast, negation, etc. Warrant A statement authorizing movement from the data to the claim. In order to move from the data established in the CLAIM, the writer must supply a warrant to bridge the gap between CLAIMS & EVIDENCE=WARRANT. Backing Data designed to certify/verify/elaborate the claims being made. Support must be introduced whenever a warrant is presented. Qualifier Words or phrases expressing the reader’s degree of force or certainty concerning the claim. Such words or phrases include “probably,” “possible,” “impossible,” “certainly,” “presumably,” “as far as the evidence goes,” or “necessarily.” The Rogerian Model Rogerian argument is a conflict solving technique based on finding common ground instead of polarizing debateAmerican psychologist Carl R. Rogers described his "principles of communications,” a form of discussion based on finding common ground. He proposed trying to understand our adversary's position, by listening to them, before adopting a point of view without considering those factors. This model is extremely useful in emotionally charged topics since it downplays emotional and highlights rational arguments. Based on “approaching audiences in non-threatening ways and on finding common ground and establishing trust among those who disagree about issues” (Everything’s an Argument). 1. INTRODUCE the problem. An introduction to the problem and a demonstration that the opponent's position is understood. 2. OPPONENT’S POSITION IS VALID. Briefly explain why this might/could be true. 3. WRITER”S OWN POSITION Although, thinking ABC, thinking in XYZ would benefit more since… The Aristotelian Model (Classic mode of argument) This form of reasoning is the opposite of Aristotelian argumentation; it is an adversarial form of debate, because it attempts to find compromise between two sides. Aristotle, perhaps the most famous arguer,described three routes to change the mind of the other person: Ethos (the source's credibility, the speaker's/author's authority) Is the writer’s reputation, their persona, and it is based on the kind of language the writer uses, the evidence they use, the respect to others, especially to those who might oppose their viewpoints. Ethos is basically the writer’s credibility, and establishing it depends both on expertise and how this is portrayed—never second guess yourself, do not write “I don’t know if this is true or not…” or other similar sentences that point to your “inexperience.” If you want people to believe you, you must first show that you believe yourself. To use credibility, position yourself as an expert. Write as if you cannot be challenged by supporting every claim you make (follow Toulmin). Do not include misspellings, obvious lapses in logic, always follow college essay format, follow directions, double check MLA citations, etc. Again, do not make mistakes in grammar, quoting, logic, tone, voice, etc. Pathos (the emotional or motivational appeals; vivid language, emotional language and numerous sensory details). Appeals to the emotions of the listener, seeking to excite them or otherwise arouse their interest. An effective way of arousing passions is in appeal to values. Ethos shows your own values and how you put others before yourself. Language has a significant effect on emotion, and key words (fire, child, anger, smooth, etc.) can trigger senses and feelings. A LITTLE GOES A LONG WAY…. Logos (the logic used to support a claim; can also be the facts and statistics used to help support the argument).Focuses first on the argument, using relevance, logic and rational explanation, as well as demonstrable evidence. This is done on the using evidence, such as science and scientific proof that is based on the use of empirical evidence. If you argue without evidence, a scientist would dismiss your argument as metaphysical (literally, outside the physical world). Evidence cannot be refuted, as courts of law seek to demonstrate. If you show, then it is very difficult to deny without calling into question the validity of the evidence produced. Evidence can include statistics, pictures and recounted experience (especially first hand). Pathos may also be evoked when giving evidence as you give it an emotional spin. Ethos is also important to establish the credibility of the witness. Reason uses rational points that call on accepted truths and proven theories. Where evidence does not exist, reason may still prevail. A common tool in reasoning is to link two items together, for example by cause and effect. Final Note Your essays should incorporate a mixture of all three modes of arguing (Toulmin, Rogerian, Classic), which means: using qualifiers, backing up claims (to produce warrants); agreeing to disagree by acknowledging other POV’s; and by balancing your role as a writer by being careful, considerate, and logical, and by ensuring that each of your claims are supported logically, by engaging your readers with vivid language and insightful observations, and by showing consideration to opponents and readers. In addition to using aspects of the three modes of argument, you must also use a mixture of these modes of development: definition, compare and contrast, negation, process analysis, descriptive language, metaphor/simile, anecdotes (when allowed), visuals, etc. You do not need to incorporate ALL modes of exposition, but you must include all three modes of argument, every time.