English 505 Rhetorical Theory Session Twelve Notes Goals

advertisement

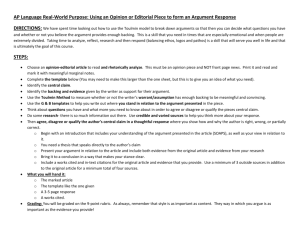

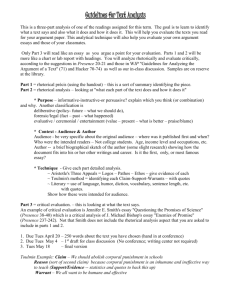

English 505 Rhetorical Theory Session Twelve Notes Goals/Objectives: 1) To begin to understand the Argumentation theories of Stephen Toulmin 2) To begin to understand the differences between Substantial and Analytic Arguments 3) To begin to understand Toulmin’s notion of Rational Assessment 4) To begin to understand the basic elements of Toulmin’s Model Questions/Main Ideas (Please write these down as you think of them) Argumentation Continued Two influential theorists interested in argumentation Stephen Toulmin – English Chaim Perelman – Belgian Provided new ways to think about argumentation Argumentation Continued First, both split with the traditional study of logic Both sought to study and understand argumentation as it actually occurs instead of as it should occur Argumentation Continued At the heart of Toulmin’s (1969) theory of argumentation is what he sees as a divergence between “the practical business of argumentation” and “the corresponding analyses of them set out in books on formal logic” Argumentation Continued Perelman adds, “As a consequence, it is necessary that we clearly distinguish analytical forms from dialectical reasoning, the former dealing with truth and the latter with justifiable opinion” Argumentation Continued Although logic may appropriately deal with deciding questions of truth based on systematic reasoning, modern argumentation theorists believe that the task of creating and evaluating statements that can be considered reasonable for a particular audience should fall to rhetoric Argumentation Continued Second, both emphasized the linguistic nature of argumentation, an approach that is directly related to their practical focus Because arguers use words and because words have ambiguous meanings . . . Argumentation Continued . . . we must include the words arguers use in any kind of study or description of argumentation Third, both focused on audience response to arguments Argumentation Continued In doing so, they paved the way for rhetorical theorists to use their theories to learn about rhetoric Stephen Toulmin Born in London in 1922 BA in mathematics and physics from King’s College in 1942 Junior scientific officer doing technical intelligence during WW II Earned an MA in 1947 Toulmin PhD in 1948 from Cambridge One of his professors was Ludwig Wittgenstein He died in December 2009 Toulmin’s classification of arguments provides a way of diagramming and critiquing arguments Toulmin The foundation of Toulmin’s contribution is the classification of two types of argument: Substantial vs. Analytic The former are evaluated according to content The latter according to form Toulmin A substantial argument involves an inferential leap from some data or evidence to the conclusion of the argument Toulmin In contrast, the conclusion of an analytic argument requires no inferential leap because the conclusion goes no further than the data contained in the argument’s premise Toulmin Individuals using analytic arguments base their claims on unchanging and universal principles Those who use substantial arguments ground their claims in the context of a particular situation rather than in abstract, universal principles Toulmin Elsewhere (in a book with Albert R. Jonsen) Toulmin describes a similar distinction between theoretical and practical arguments Theoretical = analytical Practical = substantial Toulmin The distinction between these two types of arguments lies at the base of “two very different accounts of ethics and morality: one that seeks eternal, invariable principles, the practical application of which can be free of exception or qualifications . . . Toulmin . . . and another that pays closest attention to the specific details of particular moral cases and circumstances” Thus, a theoretical or analytical argument is based on unchanging, absolute, and invariant principles Toulmin While a practical or substantial argument is based on probability and attends to the circumstances of particular cases Theoretical arguments represent idealized formal logic Toulmin Practical arguments represent everyday reasoning Theoretical or analytic argument is consistent with Plato’s ideal of formal, deductive logic that leads to absolute truth regardless of context Toulmin Practical or substantial argument conforms more closely to the ideas that Aristotle developed Practical argument is judged not by its correspondence to deductive form, but by its substance Toulmin It deals with matters of probability rather than universal truths and thus it varies according to context Toulmin Part of Toulmin’s life work was in developing an account of theoretical and practical argument that emphasizes the poor fit that follows from using theoretical argument in all commonplace situations Toulmin These situations range from how individuals consider and decide upon political issues to how they deal with personal moral dilemmas to how scientists describe their concepts Toulmin Toulmin claims that theoretical argument has been the dominant mode since the end of the Renaissance, even though it leads to largely “irrelevant claims” Toulmin He also claims that too much reliance on theoretical argument has limited the range of methods for appropriate decision making and has created its own type of tyranny Toulmin Toulmin sees his approach as an attempt to emancipate people from the “domination of theoretical argument” Toulmin’s thesis is that the doctrine of absolutism dominated Western civilization throughout the entirety of the modern period (roughly 1650-1950) Toulmin Toulmin’s approach to argumentation is rooted in an assumption of the irrelevance of theoretical argument to the assessment of everyday life The prototypical example of theoretical argumentation is the syllogism Toulmin Through a complex analysis of logic, Toulmin attempts to show that what formal logicians call premises actually serve different functions Thus, they cannot be grouped together satisfactorily Toulmin The ideal of formal logic assumes that arguments never vary regardless of their subject matter For example, formal logic assumes that the standards for judging an argument in the field of art are the same as those for physics Toulmin Formal logicians consider all arguments to be deficient unless they follow the form of deductive logic But, because all fields of human activity are not based on assumptions identical to those of mathematics or geometry . . . Toulmin . . . logical arguments are largely irrelevant to the practical world of rationality Because they derive from mathematical fields, theoretical arguments are highly impersonal Toulmin For example, the person “doing” logic is no more important to formal logic than the person “doing” mathematics is to the formula for determining the circumference of a circle Toulmin In contrast, the person engaging in argument is extremely important in rational assessment in the practical world Toulmin states that rational procedures “do not exist in the air, apart from actual reasoners: Toulmin Toulmin claims that theoretical or analytical arguments are not relevant to the world of practical affairs for a number of reasons One reason is that practical concerns are rarely – if ever – governed by a single overriding principle Toulmin A vast number of situations individuals face on a day-to-day basis are too complex to yield to a single universal principle The problems of everyday life are not simple because they vary according to the details of the situation Toulmin An example: “If I go next door and borrow a silver soup tureen, it goes without saying that I am expected to return it as soon as my immediate need for it is over” What is the universal principle? Toulmin “If, however, it is a pistol that I borrow and if, while it is in my possession, the owner becomes violently enraged and threatens to kill one of his neighbors as soon as he gets his pistol back, I shall find myself in a genuinely problematic situation Toulmin I cannot escape from it by lamely invoking the general maxim that borrowed property ought to be returned promptly” In the first example, the principle of returning borrowed goods can be applied without problem Toulmin The second situation is more problematic because the principle of requiring the return of borrowed items conflicts with a duty not to harm another person Toulmin An analytic argument will not solve this problem because no single, absolute principle exists that does not come into conflict with another equally important principle Toulmin Another reason that Toulmin considers formal logic to be largely irrelevant to practical argument is that formal logic assumes that concepts do not change over time For an argument to be valid in formal logic, “it must surely be good once and for all” Toulmin Toulmin believes, however, that most argument fields cannot accommodate timeless claims to knowledge Another difficulty is that answers to many everyday problems are either “probably correct” or “probably incorrect” Toulmin Rather than “absolutely correct” or “absolutely incorrect” Many of the questions that rational procedures are designed to answer cannot be answered with certainty Did Nixon lie when he said: “I am not a crook” Toulmin Did Clinton lie when he said: “I did not have sexual relations with that woman – Ms. Lewinsky.” The answers are probably – but not certainly – yes. Toulmin Reliance on absolute standards of judgment can lead to argumentative deadlock He uses the abortion debate as an example In some cases, the importance of absolute moral standards leads to a “tyranny of principles” Toulmin One group uses its supposed absolute principle in order to impose those principles tyrannically on all other groups and individuals One alternative to theoretical argument is relativism Toulmin According to Toulmin, this has become extremely popular in recent decades Relativism denies the existence of objective standards to evaluate concepts The only relevant standards are ones shared by groups or comm. Toulmin And standards vary across these communities The choice then is seen as limited either to a completely absolutist or a completely relativistic position – both of which Toulmin sees as untenable and unnecessary Toulmin He argues that absolute standards are so strict that they are irrelevant to the practice of rational criticism But he objects to relativistic standards because they are so imprecise that they constitute no standards at all Toulmin In other words, they can’t distinguish between a good and a poor argument Thus, Toulmin attempts to develop the notion that practical argument can and should be emancipated from “the hegemony of theoretical argument” Toulmin To free argumentation from the extremes of absolutism without falling into the abyss of relativism This is where Toulmin’s model comes in Toulmin An argument is sound if it is able to survive the criticism offered by those who participate in the rational enterprise of various fields Toulmin’s model uses the notions field-dependent and field-invariant standards Toulmin One of the ways in which arguments do not vary from field to field is that they may be analyzed according to his layout of argument His classification of arguments provides a way of diagramming and critiquing arguments Toulmin Toulmin’s model helps us to visualize how arguments are created and used It also helps us to critique arguments, because it allows us to see if parts are missing or are unsubstantiated Toulmin One example that Toulmin uses to illustrate his layout concerns a man named Harry and a claim that Harry is a British citizen This example helps to explain the basic parts of Toulmin’s model Toulmin Warrant: A man born in Bermuda is a British citizen Data (also called “grounds”): Harry was born in Bermuda Claim: Harry is a British citizen Toulmin Basic Elements A claim is the “conclusion whose merits we are seeking to establish” Brockriede and Ehninger: “The claim is the explicit appeal produced by the argument, and is always of a potentially controversial nature Toulmin Data or Grounds are the “facts we appeal to as a foundation for the claim” Data may report historical or contemporary events May take the form of a statistical compilation Toulmin Or of citations from an authority Or they may consist of one or more general declarative sentences established by a prior proof You might think of data as the evidence used to support a claim Toulmin Brockriede and Ehninger: “Data and claim taken together represent the specific contention advanced by an argument, and therefore constitute what may be regarded as its main proof line” Toulmin The claim contains or implies the word “therefore,” according to Toulmin The warrant: an arguer needs to explain how he or she moved from the data to the claim Toulmin Toulmin explains: “Our task is no longer to strengthen the ground on which our argument is constructed, but is rather to show that, taking these data as a starting point, the step to the original claim or conclusion is an appropriate and legitimate one” Toulmin Thus, we use a warrant, which functions as a bridge to “authorize the sort of step to which our particular argument commits us,” providing a rationale or justification for the claim Notice that Toulmin’s original model could easily be transformed into a formal syllogism Toulmin Major Premise: A man born in Bermuda is a British citizen Minor Premise: Harry was born in Bermuda Conclusion: Harry is a British citizen Toulmin Thus, alone, these three primary elements fail to distinguish analytic from practical arguments Because he was interested in how people argue, as opposed to more formal logic, he included additional elements into his model Toulmin A Qualifier is a statement that we make about the strength of the argument Toulmin explains that it is used “to register the degree of force which the maker believes his claim to possess” Toulmin A Rebuttal expresses some kind of exception that would negate the argument being made Toulmin’s analogy: “The rebuttal performs the function of a safety valve, or escape hatch, Toulmin and is, as a rule, appended to the claim statement” The rebuttal “recognizes certain conditions under which the claim will not hold good or will hold good only in a qualified and restricted way” Toulmin Backing consists of “credentials designed to certify the assumptions expressed in the warrant” The backing is the reason the warrant is valid Toulmin The backing is often a scientific study or law or some other form of proof for the warrant The backing should not be confused with the data, which is the initial observation or support for the claim Toulmin Toulmin explains that “Backing must be introduced when readers or listeners are not willing to accept a warrant at its face” Let’s practice Toulmin Toulmin’s model also helps us to diagram and make sense of Aristotle’s artistic proofs: ethos, pathos, logos It gives us a methodology to chart these types of arguments Toulmin What Aristotle referred to as logos, Toulmin calls “substantive arguments” Toulmin A substantive argument contains a warrant that reflects an assumption concerning the way in which things are related in the world about us The warrant in the wellness center scenario is an example Toulmin What Aristotle calls ethos, Toulmin calls “authoritative arguments” In an authoritative argument, the data consists of testimony from some person Toulmin The warrant affirms the reliability of the source from which these are derived Data: The university president stated, “Our school should build a student wellness center” Toulmin Warrant: The president of the school is thought to be knowledgeable about the school’s needs, so his or her words should be seen as credible Toulmin Claim: Our school should build a student wellness center The statement has added credibility, given the warrant Toulmin What Aristotle calls pathos, Toulmin calls “motivational arguments” A motivational argument is very similar to an authoritative argument Toulmin However, the warrant in this case provides a motive for accepting the claim by associating it with some inner drive, value, desire, emotion, or aspiration, or with a combination of such forces Toulmin In other words, data are offered that refer to some value, need or emotion humans experience The warrant affirms the presence of this value, need or emotion, and supports the claim that the data should be accepted on their appeal to a genuine human need or value Toulmin Data: Onstar is a feature in some cars that provides emergency assistance to its customers Warrant: People have a need to feel safe and secure Claim: Purchasing a car with Onstar is a good idea Summary/Minute Paper: