Notetaker: Luke

advertisement

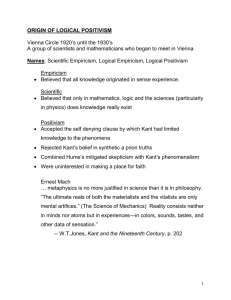

Philosophy of Science Notes (Luke Cooper) 1/20/11 – Positivism and Realism: Moritz Schlick This paper is against metaphysics, a philosophy of being, reality, and what there is. This paper was written at a time when logical positivism was relatively uncontested as truth. Logical positivism is a good place to start in the study of the philosophy of science. Included under metaphysics are realism (there is an objective “real” world out there that we all sense equally and which supplies us with “givens”) and idealism (only ideas—what is “given” to individuals through unique experiences—are real; makes no claims about an objective world that we all experience). The given can be described as “a term for what is simplest and no longer open to question” (p. 38). Logical positivists do not like metaphysicians, and even deny “the possibility of metaphysics” (p. 37). Positivism assert that “only the given is real” (p. 39), and does not concern itself with ontological claims because these claims are senseless to a positivist, in that their veridity does not have any real consequences. The realm of concern for a positivist is only that which can be verified. To an idealist, who asserts that only ideas are real, a positivist would ask, “What is the difference between these positions? We cannot differentiate between the positions of whether or not only ideas are real, so why bother?” Unlike realists, positivists do not want to go the extra step to confirm the external world; they want to stay away from things that cannot be verified. Positivists do not want to treat reality as a property. Positivists encounter difficulty when attempting to define what is verifiable: How do we know “in principle” whether or not we will be able to differentiate (i.e., verify) positions? Is Schlick discounting the possibility that we might not yet know whether or not a position could be verifiable? Are positivists backing themselves into a corner here? It seems like a metaphysical assumption to know what can and cannot be verified in principle. Positivism has a low bar of what is verifiable. But is what is conceivably verifiable relative? We discussed how the possibilities afforded by the telephone and the internet may be examples of things that were once inconceivable. We discussed the felt sensation/experience (qualia) of the color red and how we cannot (yet?) test whether or not we identically experience what we separately agree is red. We discussed whether qualia can be independent of physiology. But is the argument that experience is independent of qualia—a positivist stance—a metaphysical assumption? Schlick is worried about meaningfulness. Specifically, can one verify the verification theory of meaning? How could one verify the verification presupposition? Schlick would say that once one has insight into this presupposition, that its truth is undeniable. Schlick thinks that there can be no other way— but then how could we understand him in meaning-making if we do not agree with/understand from the point of view that he is espousing? Schlick seems to use some gerrymandering to claim that everything must start with a presupposition, and that presuppositions lay outside the realm of verification. But what difference does this all make? Does it matter if we approach meaning-making from different, unverifiable perspectives? Pantheist vs. atheist example: If a belief is unverifiable, it should have no meaning—it should not make any real difference. However, the different belief systems held by pantheists and atheists do seem to make a real difference in the way that each group approaches and interacts with the world. In response to this argument, Schlick would admit that there might be a difference, but that It would only be that one group may be subjectively happier than the other.