The British Civil Wars, 1637-53

advertisement

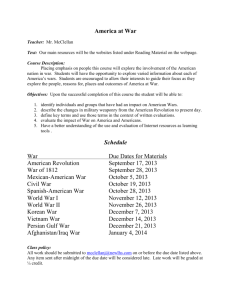

THE BRITISH CIVIL WARS, 1637-53 The civil wars of the mid-seventeenth century are one the most politically contentious periods in British history: so much so, that scholars cannot even agree on what to call them! Most people know about the English Civil War – or should we say ‘wars’? – and think they were fought by the Roundheads and the Cavaliers – although political allegiances were more complex than this contemporary binary suggests. This course uses the term ‘British civil wars’ to describe a set of interlocking conflicts that were fought in England, Ireland, and Scotland. These conflicts were hotly debated by contemporaries, even as they were unfolding, and have been subjected to competing and varied interpretations ever since. This course aims to introduce students to some of the most important frameworks and methodologies that have shaped how scholars understand the wars. In the middle of the twentieth century, there were two major approaches to what was then still known as ‘the English civil war’: the so-called ‘Whig’ and ‘Marxist’ grand narratives. The former regarded the wars as a critical period in the creation of England’s putatively unique ‘constitutional monarchy’; the latter presented the wars as a crucial transition point between the feudal society of the medieval period and the modern industrial age. One of the few points of agreement between these frameworks was that a revolution had occurred in England in the mid-seventeenth century – even if the nature of that revolution was understood in very different terms. During the last quarter of the 20th-century, a loose grouping of ‘revisionist’ historians sought to dismantle both approaches. They argued that, although England was socially, economically, and politically stable, the British ‘multiple monarchy’, comprising England, Scotland, and Ireland, was not. It was resistance to the British king, Charles I, in Scotland and Ireland that destabilized English politics. This interpretation, by emphasizing stability and consensus, stripped the wars of much of their revolutionary importance. A new generation of ‘post-revisionist’ historians, whose careers began in the 1980s and 1990s, argued that this approach ignored deep ideological and religious fault-lines in English society, while over-emphasising the influence of Ireland and Scotland on events in England. By privileging certain types of sources, it was argued, ‘revisionists’ represented ‘the last hurrah’ of the Whigs. Post-revisionists, by deconstructing over-arching narratives, helped to pave the way towards the idea that there is no single, unified ‘truth’ about the civil wars, but a multiplicity of perspectives. Scholars interested in popular politics, gender, and print culture have borrowed from other disciplines, notably the social sciences, and offered new ways of thinking about our sources. Although the civil wars as a scholarly subject have been greatly enriched by these developments, one of the more ambiguous consequences of this fragmentation has been the loss both of narrative coherence and a sense of longer-term significance. One major complicating factor has been the advent of so-called ‘new British history’, which asserted that the wars could not be understood exclusively in an English context. Yet ‘new British history’ remains bound by its ‘revisionist’ roots and has not led to new approaches to Scottish and Irish sources. English historians have begun to argue that what made the English wars ‘revolutionary’ cannot be adequately explained by looking to the British context. The large and complex historiography of the period will offer you the opportunity to examine closely the major interpretative frameworks dominating early modern history over the past century and more. By employing a variety of source materials and considering a range of approaches, the module will help you gain a deeper understanding of the methodologies that underpin early modern historical study. Prior study or knowledge of English/British early modern history is recommended for this course. No prior knowledge of Scottish or Irish history is required. INDICATIVE COURSE OUTLINE 1. Introductory session 2. Revolution? Marxists and Whigs 3. The revisionists I: ‘unrevolutionary England’ 4. The revisionists II: the ‘new ‘British history’ 5. Why Scotland is Not England 6. Reading week 7. Post-revisionism: religion and ideology 8. New approaches I: print culture 9. New approaches II: popular engagement 10. New approaches III: war, state formation, and early modernity 11. Legacies INTRODUCTORY READING M. Braddick, God’s Fury, England’s Fire (2008) B. Coward, The Stuart Age: England, 1603-1714 (2003). C. Durston and J. Maltby, Religion in Revolutionary England (2006). P. Gaunt, The British Wars, 1637-51 (1997). D. Hirst, England in Conflict, 1603-1660 (1999) A. Hughes, The Causes of the English Civil War (1998) R. Hutton, Debates in Stuart History (2004). A.I. Macinnes and J.H. Ohlmeyer, eds, The Stuart Kingdoms in the Seventeenth Century: Awkward Neighbours (2002). J.P. Kenyon and J.H. Ohlmeyer, eds, The Civil Wars: A Military History of England, Scotland and Ireland, 1638-1660 (1998). A.I. Macinnes, The British Revolution, 1629-1660 (2005) R.C. Richardson, The Debate on the English Revolution (1977; 1988; 1998). C. Russell, The Fall of the British Monarchies, 1637-1642 (1991). D. Scott, Politics and War in the Three Stuart Kingdoms, 1637-49 (2004). D.L. Smith, A History of the Modern British Isles, 1603-1707: The Double Crown (1998). A. Woolrych, Britain in Revolution, 1625-60 (2002; 2004).