From Neutrality to War: The United States and Europe, 1921–1941

advertisement

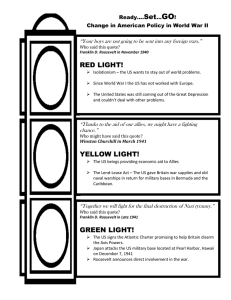

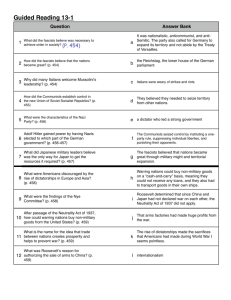

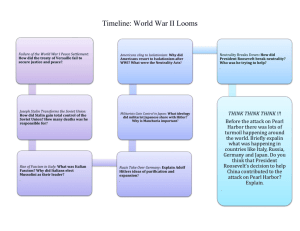

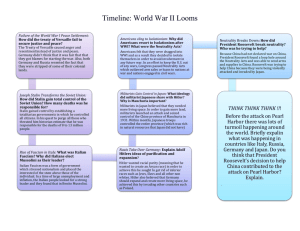

From Neutrality to War: The United States and Europe, 1921–1941 Overview In the years after World War I Americans quickly reached the conclusion that their country's participation in that war had been a disastrous mistake, one which should never be repeated again. During the 1920s and 1930s, therefore, they pursued a number of strategies aimed at preventing war. At first the major players in this effort were American peace societies, many of which were part of larger international movements. Their agenda called for large-scale disarmament and an international treaty to abolish war. Their efforts bore fruit, as 1922 saw the signing of a major agreement among the great powers to reduce their numbers of battleships. Six years later most of the world's nations signed the Kellogg-Briand Pact, in which the signatories pledged never again to go to war with one another. However, events in the early- to mid-1930s led many Americans to believe that such agreements were insufficient. After all, they did not deter Japan from occupying Manchuria in 1931, nor four years later did they stop the German government from authorizing a huge new arms buildup, or Italy from invading Ethiopia. The U.S. Congress responded by passing the Neutrality Acts, a series of laws banning arms sales and loans to countries at war, in the hope that this would remove any potential reason that the United States might have for entering a European conflict. When in 1939 war did break out between Germany on the one hand, and Britain and France on the other, President Franklin D. Roosevelt dutifully invoked the Neutrality Acts. However, he believed that this was a fundamentally different war from World War I. Germany, he believed (and most Americans agreed with him) was in this case a clear aggressor. Roosevelt therefore sought to provide assistance for the Allies, while still keeping the United States out of the war. He began by asking Congress to amend the neutrality laws to allow arms sales to the Allies. Later on, after German forces overran France, the president asked Congress for a massive program of direct military aid to Great Britain—an initiative that Roosevelt dubbed "Lend-Lease." In both cases the legislature agreed to FDR's proposals, but only after intense debate. The question of how involved the United States should become in the European war deeply divided the country. On the one hand, Roosevelt and the so-called "internationalists" claimed that a program of aid to Great Britain and other countries fighting against Germany would make actual U.S. participation in the war unnecessary. On the other side stood those who were called "isolationists," who believed that the president's policies were making it increasingly likely that the country would end up in another disastrous foreign war. This debate was still raging when Japanese aircraft attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. At this point it was clear that, like it or not, the United States would be a full participant in the Second World War.