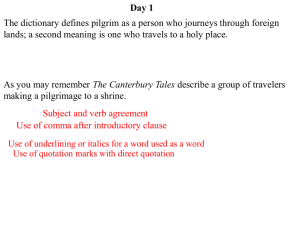

PILGRIM_S_PROGRESS

advertisement