Go to resource

advertisement

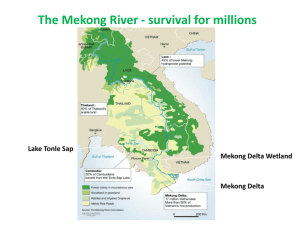

Source: http://www.wri.org/blog/2015/02/numbers-economic-impacts-climate-changelower-mekong-basin-0, Accessed 30 May 2015 Published on World Resources Institute (http://www.wri.org) By the Numbers: Economic Impacts of Climate Change in the Lower Mekong Basin by John Talberth [1] - February 24, 2015 The Lower Mekong River Basin (LMB) spans Laos, Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam, and supports 60 million people. The region is also widely recognized as highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Photo credit: William Cho, Flickr The Lower Mekong River Basin (LMB) spans Laos, Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam, and supports 60 million people. The region is also widely recognized as highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. As the world continues to warm, what will be the economic toll of climate change impacts in the Mekong region? New research [2]shows that climate change could damage $18 billion worth of infrastructure and decrease economic productivity by $16 billion annually by 2050. In a new report [2] completed for USAID’s Mekong Adaptation and Resilience to Climate Change project (MARCC [3]), my colleagues and I used a methodology known as values at risk (VAR) to assess the value of existing urban and rural infrastructure vulnerable to increased flooding and sea level rise, as well as the annual value of economic activity that will be exposed to increased heat, drought, storms and shifts in vegetation. In the LMB, these include worker productivity, infrastructure services (the annual GDP generated by infrastructure at risk), hydroelectric power generation, ecosystem services and agricultural output. The results of our preliminary analysis provide a sobering assessment of what’s at stake in the LMB. In particular, we found that: The annual value of worker productivity, infrastructure services, agricultural output, hydroelectric power and ecosystem services at risk from climate change in the LMB is at least $16 billion per year. Worker productivity represents the largest share of annual economic values at risk (52 percent). This is because so much of the LMB’s economy depends on outdoor workers engaged in construction, agriculture, fisheries and collection of nontimber forest products. These workers are vulnerable to a range of climate risks (e.g. changing flood, drought, and storm patterns), but our research points especially toward the risk of greater incidence and severity of heat-induced health disorders. Rash, fatigue, cramps, exhaustion and heat stroke could take a significant toll on these workers’ lives and livelihoods if nothing is done to protect them. A conservative estimate of infrastructure at risk of inundation in areas exposed to sea level rise and inland flooding is at least $18 billion. This includes more than $11 billion in rural infrastructure and nearly $7 billion in cities. To put these values into perspective, the $16 billion annual VAR translates into roughly 7 – 30 percent of rural GDP in the LMB. What Do We Do Now? The VAR approach does not generate precise estimates of how climate change costs will unfold over time, or where such costs are likely to manifest at a fine spatial scale. However, it does provide useful information to guide overarching policy directions that could improve climate resilience in the sectors likely to experience a high economic toll. For example, adaptation strategies to reduce the economic costs of lost worker productivity include measures such as guidelines for workplace heat assessment and protection, strengthening national health systems to respond to the specific needs of working populations, and changes in work practices such as increased rest periods during the heat of the day. Some current climate adaptation strategies—such as Cambodia’s national plan— do not incorporate these or any other measures related to worker productivity. Other important steps include: City leaders need to reduce the amount of pavement so as to combat the “urban heat island effect,” a phenomenon induced by human activities that causes metropolitan areas to be significantly warmer than its surrounding rural areas. This will require redirecting subsidies away from conventional urban growth towards green, more compact and connected cities that can make life more habitable as temperatures soar. Governments should refrain from building out new urban infrastructure in areas with anticipated increases in freshwater flooding and sea level rise. To protect ecosystem services and the livelihoods that depend on them, governments must reverse the decades-long policy of converting natural ecosystems to commercial crops and support robust ecological restoration programs. Our VAR assessment helps document the economic benefits of taking these steps towards a climate-resilient economy. As the world continues to warm, so must national and local leaders develop plans to mitigate and adapt. Quantifying the economic impacts of drought, sea level rise, flooding and more are a good place to start. Learn more: USAID: Final Three Sectoral Reports Released to Complete the Project Climate Study [4] USAID: Values at Risk from Climate Change in the Lower Mekong Basin: Interview with WRI Senior Economist and VAR Report Author [5] Source URL: http://www.wri.org/blog/2015/02/numbers-economic-impacts-climatechange-lower-mekong-basin-0 Links [1] http://www.wri.org/profile/john-talberth [2] http://mekongarcc.net/sites/default/files/usaid_marcc_values_at_risk_report_with_exesum- revised.pdf [3] http://www.mekongarcc.net/ [4] http://mekongarcc.net/news/final-three-sectoral-reports-released-complete-project-climatestudy#sthash.44gDOqkB.dpuf [5] http://mekongarcc.net/blog/interview-john-talberth-wri-senior-economist-values-risk-reportclimate-impacts-lower-mekong-ba#sthash.8PFDjEwP.dpuf