Research Methodologies

advertisement

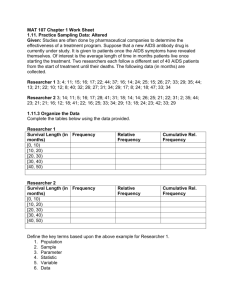

1 Research Methods For Studying Family Communication and Relationships The adept consumer of research on family processes must have an understanding of the different techniques that are employed in the design, collection, and analysis of family research studies and the data that they generate. Although a thorough treatment of these issues is beyond the scope of this book, in this appendix we provide a brief summary of some of the different research methodologies, study designs, and measurement techniques that are commonly used in research on families. More in-depth analyses of these issues can be found in Acock (1999), Copeland and White (1991), Markman and Notarius (1987), Miller (1986), Noller and Feeney (2004), and Socha (1999). Research Methodologies There are a variety of different methods that family researchers use to investigate family phenomena. Each of these methods has strengths and weaknesses. Understanding these different methods, what they can reveal, and what they cannot reveal, is useful for interpreting the results of various research studies. In this section we briefly review some of the more common research methodologies that appear in the family communication and relationships literature. Surveys The majority of what we know today about family relationships came from survey research. The common element of all survey research is that investigators ask research participants to provide information. This produces what is known as self-report data. Qualities of selfreport data are discussed in more detail later in this appendix. Ordinarily survey research involves large numbers of participants. This is because surveys are fairly easy to administer to large samples even if spread out over diverse geographic regions. Survey researchers can use the mail, telephone calls, and internet questionnaires to gather information, making it easy to reach many people. For example, the National Survey of Families and Households (e.g., Bumpass, Martin, & Sweet, 1991) involved interviews of over 13,000 households, producing one of the more intensively analyzed data sets in family science. There are a number of different data collection methods that are used by survey researchers. Perhaps the most common is the use of self-administered questionnaires. These are paper and pencil measures that are given to respondents to complete and return to the researcher. Questionnaires often contain statements and closed-ended questions that respondents answer with various numerical scales. For example, the Family Assessment Device (Miller, Epstein, Bishop, & Keitner, 1985) contains items to measure family communication, such as “People come right out and say things instead of hinting at them,” and “We are frank with each other.” Respondents indicate their answer by circling a number © Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011, Segrin & Flora, Family Communication, Second Edition 2 on a scale where 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree, 4 = strongly agree. This is known as a Likert scale. However, not all questionnaires contain closed-ended questions that are answered on Likert scales. Some might ask family members to respond to openended, essay-type questions such as “Describe your ideal family vacation.” Such questions produce qualitative data that could be analyzed or coded for various themes that appear in the answer. In some cases researcher-administered questionnaires are used instead of selfadministered questionnaires. Researcher-administered questionnaires are typically read out loud to the participant and the researcher records the answer. This can be a very useful technique for studying certain populations such as children who cannot read very well or elderly people with poor eyesight. Sometimes survey research is conducted over the telephone, in which case researcher-administered questionnaires are employed. Selfadministered questionnaires are useful when the questions are straightforward, not easily misunderstood by respondents, and when it is desirable to maintain the respondent’s privacy and anonymity. Researcher-administered questionnaires are useful when questions are complicated and might need to be clarified by the researcher and when the data are collected over the telephone or in face-to-face interviews. Many interview studies could be classified as a type of survey research. Like surveys more generally, interview methods are diverse and range from unstructured to highly structured. The more structured the interview is, the more the interviewer knows exactly what will be asked during the interview. An interview schedule is a set of questions that will be asked by the interviewer. In highly structured interviews the schedule will literally be a questionnaire that the interviewer reads to the participant, recoding answers on defined scales. In more qualitative investigations the interview schedule might involve only a general outline of issues that are to be raised in the interview. In such cases the interviewer might make decisions about what topics to pursue based on the responses of the participant. Responses to less structured interviews are often recorded through note taking or audiotape. Experiments The hallmark features of a true experiment are manipulation of an independent variable by the researcher and random assignment of research participants to the different experimental conditions. In the prototypical experiment, only the independent variable is manipulated—all other variables are controlled or held constant. This way, if the different groups (e.g., experimental vs. control) differ at the end of the experiment, that difference can be attributed to the effect of the manipulated independent variable. For this reason researchers will often design and conduct experiments when they are interested in isolating the effect of some variable (independent variable) that is assumed to have a causal effect on some outcome (dependent variable). For example, Noller, Feeney, Peterson, and Atkin (2000) created a series of audiotapes that portrayed different styles of marital conflict. These included mutual negotiation, coercion, mother-demand/father-withdraw, and fatherdemand/mother-withdraw. In this experiment Noller and her colleagues manipulated the conflict style heard on the audiotape. The tapes were then played to father, mother, and child family triads. Results indicated that the mutual negotiation conflict was viewed more © Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011, Segrin & Flora, Family Communication, Second Edition 3 positively than the other types, and that the mother-demand conflict was rated as more typical than the father-demand. Through this experiment, the researchers were able to understand the qualities of family conflict that produce positive or negative reactions in family members. As Noller herself points out, experiments have not been extensively used to study family communication and relationships (Noller & Feeney, 2004). However, experiments still represent an important tool for family researchers. Experiments are much more valuable than surveys for demonstrating causeeffect relationships. This is because they are high on internal validity. The question of internal validity concerns how confidently the researcher can conclude that the dependent, or outcome, variable was affected by the independent, or manipulated, variable. Because of their control over extraneous variables, experiments are ordinarily strong in internal validity. However, this strength comes at a price. In order to control extraneous variables (e.g., time of day, room temperature, physical environment, noise, etc.) that could affect the dependent variable, experiments are often conducted in rather artificial laboratory environments that bear little resemblance to the “real world.” Consequently, it is sometimes difficult to generalize the results of laboratory experiments to more naturalistic and realistic environments. For this reason many experiments are low in external validity, which represents the extent to which the results of the investigation can be generalized to environments and contexts external to the laboratory. Is there a happy medium between the high internal validity and low external validity inherent in most experiments? To better balance these two legitimate features of experiments, some researchers conduct quasi-experiments. Simply put, a quasi-experiment is not a true experiment because the researcher does not actively manipulate the independent variable or because the researcher could not randomly assign participants to conditions. There are naturalistic experiments going on all the time in society. For instance, Menees and Segrin (2000) were interested in the effects of various family stressors (e.g., death of a parent, parental alcoholism, parental divorce, etc.) on the social climate in families. For obvious reasons researchers could never randomly assign people to these different family stressors. Instead the authors selected people from the population who had been naturally exposed to these family stressors. The problem with this technique is that internal validity is in question. If the family environment in households with an alcoholic parent has more conflict than those that experienced the death of a parent, is that because of the nature of the two different stressors, or perhaps some other variables like education or income that also differ as a function of the stressors? It is sometimes impossible to answer these questions in a quasi-experiment. On the plus side, quasi-experiments are often much higher in external validity than laboratory experiments. After all, the people in quasiexperiments usually experienced the “manipulation” as a part of their everyday life and live with it in their natural environment. Content Analysis Content analysis is a technique for quantifying recorded communication or communication texts. So, for example, researchers might use content analysis to describe the prevalence of © Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011, Segrin & Flora, Family Communication, Second Edition 4 divorced characters on prime time television, the number of interracial families in situation comedies, or the frequency of extra-marital relationships portrayed on daytime soap operas. In the domain of family communication, content analysis is most often used to describe media depictions of family interactions and relationships. In Chapter 12 we discussed a content analysis by Robinson and Skill (2001), which showed that depictions of stepfamilies in prime time fictional television have been increasing over the years but still lag behind the actual prevalence of stepfamilies in the general population. Content analysis is a useful tool for describing what appears on television, in magazines, romance novels, motion pictures, etc., but it does not tell us who consumes these messages or what effect they have on the viewer. For example, if a content analysis showed that more divorced people were portrayed on network television in the 1990s compared to the 1960s, it would be tempting to conclude that these media depictions are at least partly responsible for the more widespread acceptance of divorce in recent years. However, this inference goes far beyond what the data actually indicate. Similarly, if a content analysis showed that family situated programs (e.g., Roseanne, The Osbournes) had more intense conflict today than they did in the past, some might conclude that this teaches young people that extensive bickering and fighting is normative in the family. As reasonable as this conclusion would appear, the content analysis alone does not tell us that young people are actually viewing these programs. That would require additional data, perhaps from a survey of television viewing habits of young people. One vital decision that must be made when conducting a content analysis is determining the unit of analysis. The unit of analysis is the basic unit or segment of the communication text that will be measured or classified. Consider for example a content analysis of family situated television programs (e.g., The Brady Bunch, Roseanne, The Osbournes). At a broad level, one could treat the entire series as a unit of analysis. For example, these shows could be classified as either “fiction” or “reality” based. At a more specific level, the unit of analysis could be the episode. Researchers could, for instance, classify each episode according to its dominant plot. Getting even more specific, individual scenes or characters could be the unit of analysis. More specific yet, a researcher could classify individual utterances of the characters on these programs. Perhaps there is more profanity used in family situated programs today than there was back in the days of Leave it to Beaver. In this case, a researcher could classify the individual utterances of each character in terms of whether or not they contain profanity. In any event, decisions about the appropriate unit of analysis are inextricably connected with the nature of the research question. If the research question concerns how often extended family members are portrayed as living in the same home, the entire series or individual episodes could be the unit of analysis. On the other hand, a research question about whether fathers are depicted as reprimanding children more often than mothers are would require a much more microscopic unit of analysis, perhaps down to the individual scene or individual utterances of each character. A second vital element of content analysis is the coding scheme. A coding scheme is simply a classification system for describing the content of the communication text. For example, a © Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011, Segrin & Flora, Family Communication, Second Edition 5 content analysis of family roles in motion pictures might include the following categories: mother, father, husband, wife, son, daughter, brother, sister, grandfather, grandmother, aunt, uncle, stepmother, stepfather, cousin. Researchers could then classify each character into one of these categories to see what family roles are most and least commonly portrayed in the movies. Coding schemes used in content analysis must have categories that are mutually exclusive. This means that each unit to be coded can be classified into one and only one category. What if the coding scheme above was used to classify Kevin Spacey’s character in the film American Beauty? He was both a husband and a father. As straightforward as this coding scheme appears, it could be problematic when actually getting down to the business of coding real communication texts. A coding scheme must also be exhaustive. This means that there is a category for every unit to be coded. What if a character in a film was the brother-in-law of another character? The scheme presented above has no category called “brother-in-law,” so it is not truly exhaustive. Sometimes researchers will make exhaustive coding schemes by using an “other” category for all those units that cannot be fit into one of the existing categories. Finally, there are some cases in family research where content analysis is used as a method of analyzing data that were gathered as part of an interview or survey research study. For example, Fiese and her colleagues interview families and record narratives or stories about their experiences (Fiese et al., 2001; see Chapter 3). These stories would then be transcribed and essentially content analyzed for narrative coherence (how well the story is constructed and organized), narrative interaction (how well the family works together to jointly construct the narrative), and relationship beliefs (the way that the family’s view of the social world is reflected in their story). In this way, content analysis is useful for summarizing and cataloging the qualitative data that are provided by research participants. Ethnography Ethnography is a type of qualitative field research that is aimed more at description than explanation. In particular, ethnographic studies examine various phenomena in their natural settings rather than in laboratories. Unlike experiments or surveys, in ethnography investigators will often get directly involved in the subject matter that they are studying and interact frequently with the research subjects. The idea is that the closer one’s contact is with the phenomenon under investigation the better able he or she is to offer a detailed and accurate description of that phenomenon. Ethnographic studies tend to follow the grounded theory approach. Researchers who develop grounded theories start with careful and detailed observations and then develop more general theoretical explanations based on those descriptions. This is more of an inductive than deductive approach to theory development. In ethnographic research there are a number of different relationships that might exist between the researcher and his or her research subjects. When the researcher acts as a complete observer he or she simply observes phenomena as they occur in their natural environment. In such cases the research subjects are unaware of the ethnographer’s © Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011, Segrin & Flora, Family Communication, Second Edition 6 observations and are therefore unlikely to alter their natural behavior. In a closer level of involvement with research subjects, ethnographic investigators sometimes assume the role of observer as participant. In such cases research participants know that they are being observed but the researcher tries to “fit in” to the situation or context without actually participating in it. When researchers act in the role of participant as observer they actively participate in the phenomenon under investigation. For example, if an ethnographic investigator attended a family reunion and ate hotdogs and talked with various family members, he or she would be acting as a participant observer. This perspective gives the researcher considerable insight into the phenomenon under investigation but this familiarity comes at a cost as the researcher may actually influence the phenomenon that is being studied. Finally, ethnographic researchers sometimes act as complete participant. In this case they actively participate in the phenomenon that is being studied but do not inform research participants of their dual role as both participant and researcher. This is comparable to being an undercover police officer. If the behavior being observed is public, this is not a problematic technique, but if it is private there are obvious ethical issues associated with the difficulty of securing informed consent from the potential research participants. Ethnographic researchers use a variety of creative methods to make their observations. These might include, for example, interviews, careful note taking, and audio or video recordings. Sometimes research participants are asked to listen to or watch audio or video recordings of their own behavior, and to comment on or explain that behavior. This technique is known as stimulated recall. Ethnographic methods have not been as widely employed to study family communication and relationships as surveys have been, but nevertheless they hold great promise for providing detailed descriptions of such relationships and interactions. In one notable exception, an ethnographic researcher actually lived with a family for a period of time in order to observe and better understand the family’s television viewing patterns and habits (see Fiske, 1987). This sort of investigation yields a depth of knowledge that is not ordinarily available in the typical laboratory experiment or survey study. On the other hand, the ability to generalize from the results of observing a few cases in depth is extremely limited. Another potential problem inherent in some ethnographic investigations is reactivity. This occurs when research participants alter their behavior because they know that they are being observed. Of course, this is a problem inherent in many different research methods and is not unique to ethnographic research. Research Designs Regardless of the method a researcher chooses, there are several design issues that must be considered when planning the study. Three major design features that we will discuss in this section are cross-sectional versus longitudinal designs, and meta-analysis. Although the © Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011, Segrin & Flora, Family Communication, Second Edition 7 longitudinal vs. cross-sectional distinction is often thought of as being most applicable to survey research, experiments and content analyses could also be longitudinal in nature in some instances. Cross-Sectional Designs A cross-sectional study examines a representative sample, or cross-section, of the population at one point in time. For this reason, cross-sectional studies are very useful for describing the status quo in a segment of the population. For example, large-scale surveys that measure rates of family violence, number of divorced people in the population, and levels of marital satisfaction in husbands and wives are often cross-sectional in nature. Such studies can tell us things like X% of husbands are dissatisfied with their marriages and Y% of wives are dissatisfied with their marriages. For many purposes, this can be useful information. At the same time, however, there are some drawbacks to cross-sectional designs. First, if the phenomenon is one that is actively changing throughout history, the results of a crosssectional survey might have a limited shelf life. If someone wanted to know what percentage of married women stay home to raise their children instead of working outside the home, a cross-sectional survey conducted in 1962 would be of little use. This is because women’s participation in the professional workforce has changed substantially since 1962, and those results could not be assumed to accurately reflect current rates of mothers’ participation in the workforce. Second, cross-sectional studies are limited in the extent to which they can provide information on causeeffect relationships. Consider two competing models of marital satisfaction and conflict. According to the first model, conflict causes marital dissatisfaction (conflict dissatisfaction). According to the second model, marital dissatisfaction causes conflict (dissatisfaction conflict). Suppose a researcher conducted a survey study of 1000 married people and asked them to report on their level of marital satisfaction and the frequency of their marital conflicts. If the results indicated a significant correlation between conflict and dissatisfaction does that support model 1 or model 2? In fact both models 1 and 2 could be correct. If A causes B, A and B must be correlated with each other. Also, if B causes A, A and B would still be correlated. Furthermore, a significant correlation between conflict and dissatisfaction could occur even if both model 1 and model 2 are incorrect. If some third variable, say marital infidelity, caused both marital dissatisfaction and marital conflict, dissatisfaction and conflict would still be correlated despite having no causal relationship to each other. For this reason it is important to remember that in cross-sectional studies a significant correlation does not imply a causal relationship between. Longitudinal Designs A longitudinal study is designed to observe and study phenomena over time. As noted in our discussion of cross-sectional studies, many family phenomena change over time. Only a longitudinal study can adequately document that change. There are several different types of longitudinal study designs that are used to study different types of change. For example, the trend study examines changes in the general population over time. The U.S. Census © Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011, Segrin & Flora, Family Communication, Second Edition 8 Bureau measures households and living arrangements in the American population every 10 years. An examination of cohabitation rates as documented in the 1970, 1980, 1990, and 2000 census would amount to a trend study. Such an investigation would allow the researcher to examine trends in cohabitation to see if it is on the rise or decline in the U.S. population. In a cohort study researchers examine changes in a certain subgroup, or cohort, in the population over time. Suppose that a researcher was interested in the “family values” of people born during the great depression of the 1930s, and how they changed over time through the varying political climates of the 1960s, 1980s, and so on. This could be accomplished by surveying a group of people born in the 1930s every 10 years. For example, the first wave of measurement might start in 1950 when members of this cohort are in their 20s. The next wave might occur in 1960 when these people are in their 30s, followed by a wave of measurement in 1970 when they are in their 40s, and so forth. This type of study would allow researchers to track changes in the family values of this cohort over extended periods of time. Perhaps their family ideologies are relatively stable despite dramatic shifts in the social climate over time. A cohort study could reveal such a finding. Perhaps the most powerful longitudinal design is the panel study. In the panel study the same people are followed over time. In others words a person who is measured at time 1 is also measured at time 2. In the trend and cohort studies different people are measured at each point in time. The panel study allows researchers to track changes within particular individuals. Why is this such a useful and powerful research design? Scientists and philosophers generally agree that in causal models, cause must precede effect. Only a panel study can show that a supposedly “causal” agent happened and was then followed by a hypothesized “effect” in the same person. For example, in Chapter 11 we discussed a study by Huston and Vangelisti (1991), which showed that wives’ negativity (e.g., acting bored or uninterested, showing anger or impatience, criticizing or complaining) during a marital interaction predicted decreases in their satisfaction two years later. Only a panel study could test this negativity in interaction dissatisfaction hypothesis, because is it necessary to demonstrate that the negativity happens before the dissatisfaction does. Interested readers might want to examine Karney and Bradbury (1995) for more examples of panel studies with married couples. The useful information that is yielded by panel studies comes at a high price—literally and figuratively. Often families have to be compensated for their time and involvement. It can take an enormous amount of money to conduct large sample studies that follow people over many waves of assessment. Panel studies also have the unique problem of attrition. Attrition occurs when people drop out of a panel study before it is finished. Why is this a concern? Consider Huston and Vangelisti’s (1991) study mentioned earlier. What if half of the husbands and wives dropped out of the study before the two years were up? One might be concerned that only the happy couples stayed in the study. After all, who wants to tell the whole world about their bad marriage? In contrast, maybe more of the dissatisfied spouses stayed in the study because they have some sort of axe to grind and want to vent and unload on the researchers. Either way, there is a concern that this attrition effect is not random and may therefore bias the results. Another problem that is inherent in panel studies with two © Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011, Segrin & Flora, Family Communication, Second Edition 9 waves of measurement is statistical regression. This is simply the natural tendency of people with extreme scores to become less extreme over time. Imagine a couple with extraordinarily high or low levels of marital conflict. Most likely, one year later the couple with high conflict will be reporting slightly less conflict and the couple with virtually no conflict will be reporting higher levels of conflict. This natural occurrence happens because it is difficult to sustain extreme levels of conflict (or just about anything else) over long periods of time. For the panel study, this creates questions about “meaningful” change that is driven by some family process versus simple regression toward less extreme scores over time. Even though longitudinal studies can document change over time, it is important to recognize their limitations. Assume for example that a researcher measures a variable, X (marital infidelity) and its effect on variable Y (divorce) at a later point in time. An association between these two variables over time might lead some to suspect that marital infidelity is a cause of divorce. However, what if some third variable Z (psychological detachment from the marriage) causes both X and Y? This situation could make it appear that X causes Y, when in fact their association is largely coincidental by virtue of each being caused by some common third variable. The potential for misattributing causal order is especially high when the effect of Z on Y takes longer to happen than X on Y. As Glenn (1998) noted, longitudinal studies, like all other studies, are limited in their ability to rule out these “third variable” explanations. Nevertheless, because temporal precedence of cause before effect is a necessary but not sufficient criterion for establishing causality, longitudinal studies are useful for at least falsifying hypothesized causal effects and still play a vital role testing causal models (Rogosa, 1979). Despite the costs and potential pitfalls inherent in panel studies, in many ways they represent the pinnacle of family science research. When studying phenomena that naturally develop over time such as marital distress, children’s communication skills, and stepfamily cohesion, there is really no parallel to panel studies and for that reason alone they merit special attention. Meta-Analysis As the name implies, a meta-analysis is literally an analysis of analyses that have already been conducted. In a primary research study, data points ordinarily represent variables measured from individual people. However, in a meta-analysis data points represent findings from an entire study. The purpose of a meta-analysis is to quantify how strong the association is between variables (e.g., family cohesion and child adjustment), or how strong the difference is between groups (e.g., married and divorced), and to summarize all of the findings that are available on a particular topic. These statistics that represent how strongly variables are associated or how strongly groups differ are known as effect size estimates. A meta-analysis provides effect size estimates that are averaged over all of the known studies on a particular topic. It is becoming increasingly common to see meta-analyses of dozens, if not hundreds, of studies in a single investigation. Often these studies collectively involve 10,000–20,000 research participants. For example, Amato and Keith’s (1991a) meta© Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011, Segrin & Flora, Family Communication, Second Edition 10 analysis of the effects of parental divorce on children’s social adjustment involved 92 studies. Over 13,000 children participated in these studies. The benefit of conducting metaanalysis becomes obvious when considering the vast amounts of data that can be summarized in a single report. Further, meta-analyses report how strongly variables are associated or groups differ, not just whether or not they are associated or different. Because individual studies can have problems or weaknesses, their results are sometimes open to different interpretations. By accumulating results across many different studies, the weaknesses of one study are often mitigated by the strengths of others. Like panel studies, meta-analyses warrant special consideration for the wealth and conclusiveness of information that they can provide. Measurement in Family Research Aside from the methodology of a study (e.g., experiment, survey) and its design (e.g., crosssectional, longitudinal), studies also vary in the type of measurement that they employ. There are a number of different ways to measure family phenomena that are of interest to researchers who study them. Undoubtedly, the two most common types of measurement in family science are self-report and observation. We will discuss the pros and cons of these measurement strategies and then briefly consider the use of other sources of data such as physiological and phenomenological data. Self-Report In the section on surveys we indicated that much of what we know today about families comes from survey research and that these data are largely self-report in nature. In selfreport measurement, the researcher simply asks participants to provide information in response to various questions or agreement with different statements. Family scientists have developed a multitude of different self-report instruments for assessing various family-related variables. A small sample of some of the more commonly used self-report instruments in family research appears in Table A.1. Instruments such as these are very popular in family research because they can be completed with relative ease and because they can rapidly provide useful information on variables that are sometimes difficult or impossible to actually observe. Noller and Feeney (2004) identify many useful qualities of self-report data in family communication research. First, they are useful for collecting information about family communication across time and situations. If a researcher wanted to know if a mother was strict with her children both in the home and when they are away from home, self-report measurement would be a good way to gather this information. It would be extremely difficult to observe the mother interacting with her children in their home, at the grocery store, at their grandmother’s house, at church, at the movies, and so on. It is much easier to simply ask the mother, and perhaps her children as well, about family discipline practices in a number of different contexts. Second, self-report data are useful for collecting information © Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011, Segrin & Flora, Family Communication, Second Edition 11 on communication that happened in the past. Does a history of childhood abuse predispose people to stormy marriages as adults? Ideally, one would follow groups of abused and nonabused children through adulthood and into marriage. However, such as study could take 2030 years to complete. On the other hand, a researcher could collect self-report data on childhood experiences with abuse and current marital adjustment in a sample of married adults. This method is not without its shortcomings as we will discuss momentarily. Noller and Feeney (2004) note that self-reports are also useful for gathering information on behaviors that are unlikely to be elicited in a laboratory setting. Marital violence, withdrawal, and sexually oriented nonverbal behaviors are unlikely to occur in a laboratory. Nevertheless, they could have a substantial impact on the quality of a relationship. The only sensible recourse for scientists interested in studying these behaviors is to simply ask people about their occurrence and their feelings about them. We might add to Noller and Feeney’s list the fact that self-reports are also useful for measuring people’s attitudes about family members and family communication, because these are otherwise not directly observable. For example, measurement of marital satisfaction is essentially an attitude toward, or evaluation of, one’s marriage. Although it might have observable behavioral manifestations, the evaluation itself can really only be measured through self-report. Just as there is obvious utility in self-report data, there are a number of limitations to selfreport data that are often discussed in the research literature. For example, social desirability is a problem when people purposely distort the truth in order to present themselves in a positive light. For this reason a self-report study of marital violence is likely to underestimate the true incidence of the problem because some people may be unwilling to admit that they have either perpetrated or been the victim of domestic violence. There are also problems with recall bias any time that retrospective reports are sought. No one has a perfect memory and sometimes people remember mostly the good times from their family experiences during childhood. Others may be prone to only remember the bad times. A lot of this bias in recall could be explained by people’s current emotional state. Either way, important details from the past might get lost with self-report data. A related problem with retrospective self-reports is mentally editing past experiences. This is different to selectively forgetting. All people think about many of their past experiences and try to make sense of them. As they do, details sometimes get edited or changed to fit a particular schema or belief system. For example, a divorced father who was distant from his children back when he still lived with them may think back to those days, overestimating how much time he actually spent with his children. It is not that the hypothetical father is being dishonest. That is the way that he really remembers the days living at home with his children. These types of distortions in memory create an interesting dilemma for researchers. What is more important, what “really” happened or people’s perceptions of what happened? This is a thorny issue that boils down to one’s view of “objective reality,” and whether or not people feel that there even is such a thing. Family researchers will sometimes use specialized techniques to overcome some of the limitations of self-report data described above. For example, some researchers use a diary method (Duck, 1991) that asks participants to record their thoughts or behaviors at some © Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011, Segrin & Flora, Family Communication, Second Edition 12 regular interval (e.g., each night). With this method scientists can analyze the accumulated diary records with reasonable confidence that participants did not forget important details because their self-report data were provided in close proximity to when the events or thoughts occurred. In some cases family researchers use experience-sampling techniques (Noller & Feeney, 2004) such as beepers or repeated telephone calls to collect data. Participants in such studies might receive a phone call from the researcher or respond to a pager that goes off at random times. Once again, the idea is to collect data on what is going on “right now,” rather than wait until later when the person might have forgotten certain details of the day’s events. By using the specialized technique at least some of the limitations of self-report measurement can be effectively minimized. Behavioral Observation Observational studies of marital and family interaction have become increasingly popular in the past 20 years. This is due in part to the availability of affordable audio and video recording devices and media. In observational studies researchers observe and record family members as they interact with each other. These studies are usually done in a laboratory, but with the availability of portable audio and video recorders home observations are used in some cases. The purpose of an observational study is to assess family members’ actual communication behavior and determine how those behaviors are related to various family processes that may be of interest to the researcher. There are several design elements of observational studies that must be considered before the study is conducted as well as when interpreting the data that were produced from the study (Markman & Notarius, 1987). First, researchers must decide what task they want the family members to engage in. Observational research on marital interaction for example has been dominated by conflict resolution tasks. Typically husbands and wives are asked to discuss and attempt to resolve some area of conflict in their relationship. Even observational studies of larger family interactions that include children are often focused on a problem-solving task. The task that research participants engage in will determine to a large extent how far the results of the study can be generalized. A study that observes married couples attempt to resolve a conflict can reveal a lot about their conflict resolution skills but say very little about how much they enjoy leisure time together. The selection of a task obviously must serve the overall purpose of the study. Another feature of observational studies is the setting. As mentioned above, observational studies are most often carried out in a laboratory setting but could also occur in a home environment or in some other setting (e.g., a day care center, nursing home, pediatrician’s office, etc.). Earlier we mentioned that laboratory experiments are sometimes criticized for having questionable external validity. In many ways, the same concern could be raised with observational laboratory studies. Are the behaviors that are observed in a laboratory similar to those that are enacted in the home? Will parents who hit their children also enact this behavior during a laboratory interaction? Will verbally aggressive married couples put each other down as intensely as they do when they are not sitting in front of laboratory video cameras and one-way mirrors? Answers to these questions are not always known and © Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011, Segrin & Flora, Family Communication, Second Edition 13 get to the heart of the external validity of laboratory studies. It is precisely for this reason that some researchers opt to observe families in more natural, but less controlled, settings such as their homes. For those who are particularly concerned with the artificiality of laboratory observational research, it is useful to consider that what is observed in the lab is probably an understatement of what actually goes on in the home, away from the camera and observers. Therefore, if some behavior observed in the lab (e.g., contempt for the spouse) is predictive of some outcome (e.g., divorce), it is unlikely that the laboratory research results are overstating the case for the contempt divorce association. Again, the nature of the contempt that might be observed during a laboratory interaction is most likely an under-representation of the couple’s actual communication behavior. So the results that are produced by such a study are probably a conservative statement about the effects of contempt. In addition to the task and setting, observational researchers must consider the family composition. Some observational studies examine interactions between husbands and wives, others look at mothers and their children, and still others observe whole families interacting. Here again, the decision about family composition will have a large impact on the nature of the data that will be gathered. For example, husbands and wives will most likely alter their communication behavior when in the presence of their children. Of course, if a researcher observed that they did not, that would be diagnostic in and of itself. Children interacting with their mothers might also adjust their communication behavior when in the presence of their father. Like the interaction task, the family composition must be matched to the purpose and goals of the study. Once the family observational data are collected, usually on audio or video tape, they need to be organized and summarized. This is most commonly accomplished through coding or rating the interactions. Coding works exactly like a content analysis. Examples of various communication behaviors or acts are tabulated, usually for their frequency, but sometimes for their duration or sequencing with other behaviors. Rating typically involves some judgment or evaluation of the observed behavior on a set of scales. For example, a researcher might rate a mother’s behavior toward her child during a problem-solving task on the following scale: unfriendly 1 2 3 4 5 friendly Ratings such as this tend to be more global or macroscopic, whereas coded behaviors are often more microscopic in nature. Family researchers have developed dozens of excellent coding schemes for assessing family interactions (see for example Kerig & Lindahl, 2001; Markman & Notarius, 1987). Examples of some of the more commonly used coding and rating schemes appear in Table A.2. Notice how each of these schemes has a very different purpose that is obviously reflected in the types of codes that appear in the scheme. For example Patterson’s FICS scheme was developed to assess positive and negative behaviors that occur in whole family interactions that include children. Many of these are nonverbal © Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011, Segrin & Flora, Family Communication, Second Edition 14 behaviors. On the other hand Hahlweg et al.’s (1984) KPI is designed to catalog the discourse of married couples as they talk with each other. Needless to say, observational research can be very time consuming, expensive, and difficult to conduct. So why bother? Perhaps the most compelling reason for doing observational research is the hope of assessing behaviors that actors might not always be consciously aware of, but that still have a substantial impact on family processes. Sometimes people do not realize just how often they say or do certain things. Other times they might realize it but are not willing to admit it. Observational research can be a very useful tool for getting around many of the problems inherent in self-report data collection. There is also a great purity in behavioral assessment. Reports and recollections of family behaviors can often be distorted for a variety of reasons. On the other hand, there is a greater degree of objectivity in observation of family interactions. This type of data collection does not rely on family members’ recollections or perceptions. Of course there are downsides to observational studies as well. Just because a researcher documented that mothers smiled more at their children than fathers did, for example, does not prove that this behavior means anything to the children or that they even noticed. Also, there is a serious question of generalizability from observational studies. It is often possible to only observe family members interacting for 10 or 15 minutes. Can such a small sample of behavior reveal much about the family? Remarkably, in some cases, the answer appears to be yes. Also, observational studies are difficult to conduct because they are time-consuming, expensive, and create logistical challenges for getting multiple family members in a laboratory all at the same time. Once their data are recorded coders sometimes spend hundreds of hours analyzing and cataloging the recorded behaviors. Despite all of these costs, many researchers remain convinced of the value of observational research, as family scientists Howard Markman and Clifford Notarius (1987) argued: “We remain convinced that the proximal source of family distress and well-being lies in the microlevel of exchange between family members” (p. 385). This microlevel exchange can only be studied effectively through observational research. Other Measurement Techniques As family science progresses researchers are finding great utility in measures other than self-reports and behavioral observations. For example, physiological measures indicative of arousal such as heart rate and blood pressure have proven to be useful for understanding marital interactions (Gottman & Levensen, 1988). Also, levels of stress hormones circulating in the blood during marital conflict discussions are predictive of divorce and marital satisfaction 10 years later (Kiecolt-Glaser, Bane, Glaser, & Malarkey, 2003). Phenomenological research often employs interviewing for example, but might also employ techniques such as picture drawing to understand children’s relationships and interactions with family members (Davilla, 1995). These symbolic creations along with other activities such as playing with dolls might contain information on children’s representations of their roles in the family and relationships with other family members. Like all other measurement techniques, physiological and phenomenological measures have their strengths and weaknesses. However, in combination with other measures they often prove © Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011, Segrin & Flora, Family Communication, Second Edition 15 to be useful for revealing additional information that may not be evident from some of these more standard measurements. © Routledge/Taylor & Francis 2011, Segrin & Flora, Family Communication, Second Edition