The Story Behind Atomic Theory Introduction

advertisement

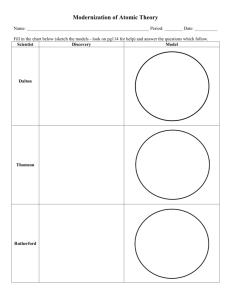

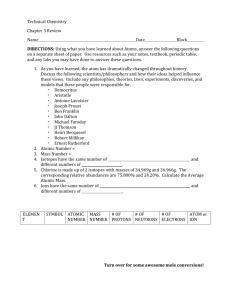

The Story Behind Atomic Theory Introduction Meet Democritus Chemistry is the science of matter. You should already be familiar with concepts like substances, elements, compounds, molecules, and other such terms. Ever wondered though, what are all these things made of? Let’s use Lego® as an example. I have a nice house made of Lego® pieces. Now, if I break down this house, I’ll have walls and windows and a door. I can break down these further, and even further, until I get an individual, smallest piece of Lego® that still retains the properties of the house (in this case, colour and texture). Does this work in nature? And if so, who thought of it? Atomic theory is a theory that attempts to answer that question. It states that all matter is composed out of extremely small particles called atoms. An atom is the smallest particle that retains the properties of an element (so a carbon atom would still have the properties of carbon, but if you break the atom down these properties will disappear). This theory, although it sounds simple, is in reality extremely complex. It eliminated the notion that matter like water would never stop being water no matter how small a quantity of it you have. Although it’s still only a theory, nowadays, it is widely accepted and supported by virtually everyone. And like most theories, the atomic theory has great story and history behind it. Like most modern science, the atomic theory started in Ancient Greece. The guy who thought it all up was known as Democritus, a materialist philosopher, in the 5th century BC. He thought very hard about matter and the universe, and came up with an idea. Democritus stated that all matter is made up of units that move around in a void. Democritus believed that these units are indivisible and unchangeable. In fact, he decided to call them atomos, which means uncuttable in Greek. Although these atomos are all made up of the same matter, their shape, size, and orientation in space explains the existence of different substances and materials. While most of Democritus’ ideas aren’t acceptable today (atoms are divisible into smaller units, and they are in constant change), the revolutionary thought that matter is composed of tiny particles moving in a void is accepted today as the basis for modern atomic theory. For hundreds of years after this, nobody cared, and atomic theory wasn’t explored. People either accepted the notion that matter can be divided into infinitely small amounts without a change in properties, or that there’s something that makes up matter, but since nobody could really check, it made no difference. Adapted from http://chemistry.learnhub.com/lessons Ms. Withrow 2008 1 The Story Behind Atomic Theory John Dalton’s Atomic Theory There are a few important rules that came about in the late 1700s that were crucial to Dalton’s thoughts. First was the Law of Conservation of Mass. This law, formulated by Lavoisier, states that during a chemical reaction, the total mass of the reactants equals the total mass of the products. This suggested that matter is indestructible. The second law was called the Law of Definite Proportions proposed by Proust. The law states that whatever quantity of substance you take, the proportions of the masses of elements composing this substance will always remain equal. For example, the ratio of oxygen to carbon in a tiny vile of carbon dioxide will equal the ratio of O to C in a large container. In an attempt to explain how and why elements would combine with one another in fixed ratios and sometimes also in multiples of those ratios, Dalton formulated his atomic theory. Here are the main points of Dalton’s atomic theory: All elements are made of tiny particles, called atoms. All atoms of one element are identical, though atoms of different elements are different, specifically in terms of mass. Atoms can’t be created, destroyed, or subdivided. Atoms of one element combine with atoms of another element to form compounds. The molecules of these compounds always have the same proportions of elemental atoms. It’s worth noting that this theory isn’t totally accepted today- lots of improvements were made over the years. For example, we now know that atoms can be subdivided into protons, electrons, and neutrons. Once this theory was introduced, things started to move a lot more rapidly. Everyone seemed to be researching this or that, trying to find out something worthy and get into the history (and science) books. JJ Thomson’s Discoveries By the 1850s, scientists began to realize that the atom was made up of subatomic particles that were thought to be positively and negatively charged. During this time scientists began to study electrical discharge through cathode-ray tubes (think neon signs). These were partially evacuated tubes in which a current passes through forming a beam of electrons. This beam moves from the cathode (positive end) to the anode (negative end). The electrons cannot be seen, but it was found that certain materials fluoresce (give off light) when energized. JJ Thompson observed that when a magnetic or electric field are placed near the electron beam, they influence the direction of flow – opposite charges attract each other and like charges will repel. He also found that the magnetic field forces the beam to bend, depending on its orientation. From this Thompson concluded that: (1) cathode rays consist of beams of particles and (2) the particles have a negative charge. Adapted from http://chemistry.learnhub.com/lessons Ms. Withrow 2008 2 The Story Behind Atomic Theory However, this wasn’t all. Thomson understood that all matter was inherently neutral, so there must be a counter to this negative charge, a positive charge. But where to put it? He suggested that the negative charges were balanced by a positive umbrella-charge as shown in the picture below. From this, Thomson described the atom as having an umbrellacharge, also known as a positively charged electron cloud, with negatively charged electrons flowing freely throughout. This model is often referred to as the “plum pudding model” or the “chocolate chip cookie model” because of its resemblance to these things. The dough in the cookie represents the positive umbrella-charge while the chocolate chips represent the negatively charged electrons. Ernest Rutherford “The Father of Nuclear Physics” Rutherford, who was Thomson’s student, is widely known for the Gold Foil Experiment. This experiment was simple – you take a really thin foil of gold, a few atoms thick, and bombard it with positively charged alpha particles. According to the cookie model proposed by Thomson, the particles should pass through undisturbed. Above is a picture of the Gold Foil experiment. The real results of this were shocking- while most particles passed through undisturbed, a few were heavily deflected. In 1911, Rutherford finally published a solution to this odd result- the cookie model is wrong. Atoms aren’t made of electrons with positive dough around them. Based on this work, and contributions from other scientists, Rutherford developed a new model of the atom. This model introduced the nucleus – a centre where the majority of the atom’s mass and charge is located. His nucleus contains protons and neutrons and has an overall positive charge. The remaining area of the atom was an electron cloud, negatively charged, making up the majority of the atoms volume. This model of the atom is pretty much what we use today: a nucleus with orbiting electrons around it. It gets a little more complex than this, but we will leave that for another time. Adapted from http://chemistry.learnhub.com/lessons Ms. Withrow 2008 3