`Fresh Moves` Produce Market: Greening the (Food) Desert

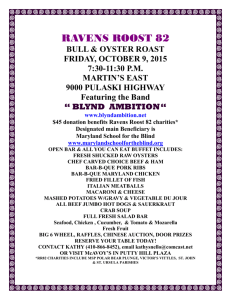

advertisement

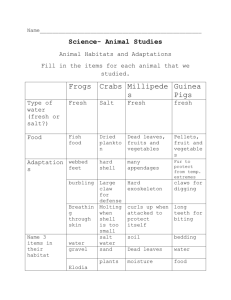

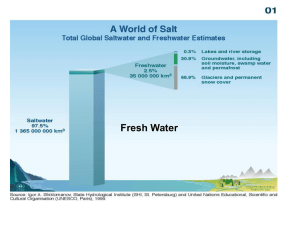

‘Fresh Moves’ Produce Market: Greening the (Food) Desert With help from Architects for Humanity, a “mobile food market” is bringing fresh fruits and vegetables to some of Chicago’s neediest neighborhood By Angie Schmitt It’s a Friday morning in west Chicago neighborhood of Garfield Park, and a brightly colored bus is idling out front of a corner store, advertising cigarettes, cold cuts, and pop. From a van in the opposite corner, a handful of people are working to unload and load a parade of produce: tomatoes, kiwi, pineapple, kale, green beans, mint, bananas, and grapes, some of which is grown locally. In about an hour, the former Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) bus, wrapped in an advertising sheath that says “Fresh Moves Produce Market,” is packed and ready to go. Unfolding on this corner is the new model for fresh produce retailing in Chicago. It begins here in Garfield Park, and then winds its way to North Lawndale, then on to a school and a senior housing facility in the Austin neighborhood. Everywhere this bus travels is part of a food desert– neighborhoods where mangos and radishes are scarce but where fried chicken and potato chips are not. This is a national problem, but one that is especially pronounced in Chicago, particularly here on the historically impoverished South Side and West Side. Nationally, about 2.3 million U.S. families live more than one mile from the grocery store and lack access to an automobile, according to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). The landmark study completed six years ago that popularized the term “food desert” found that 600,000 people in Chicago alone suffered from limited access to healthy foods. Minority communities are particularly vulnerable to the negative health impacts that The Fresh Moves Produce Market bus. Image courtesy of Architecture for Humanity. The interior of the Fresh Moves bus. Image courtesy of Architecture for Humanity. come with a lack of access to fresh fruits and vegetables. Research has found that African-Americans living in food deserts are significantly more likely to die from poor diet. As the Fresh Moves bus winds its way through the streets, men and women–some confidently (regulars), some hesitantly (“you’re selling fruit?”)–climb aboard and find what looks very much like a produce aisle in miniature. Along the sides, seats have been replaced with stacked shelves where some 50 types of fruits, vegetables, and fresh herbs are organized inside labeled tubs. In the back there’s a cash register, a hanging scale, and even a folding counter, where a stack of recipe cards is perched. Shoppers linger, searching, and deciding. The power to visualize Julie Davis shops here weekly on her lunch break. She grew up in North Lawndale and now she works in the neighborhood. Now in her 30s, “It’s always been an issue finding fresh produce,” she says. “A lot of children here, if they go to a corner store, there might not be any. If you get used to not seeing it, it kind of becomes a way of life.” Fresh Moves co-founder and board president Steven Casey lives in a food desert himself: the Inglewood neighborhood. The critical difference between Casey, who works for the MacArthur Foundation, and many of his neighbors, however, is that his family owns a car, putting many alternatives within reasonable reach. Following release of the troubling food desert report in 2006, community activist Jeff Pinzino reached out to Casey. The two briefly considered trying to tackle the problem with brick-and-mortar grocery stores. But at that time, the nation was just beginning to feel the effects of a long and painful real estate crisis, and the costs would have been prohibitive. But the pair was aware of a produce market in Oakland, Calif., that operated out of the back of a postal truck: The People’s Grocery. Another epiphany came when they learned that CTA is required by federal statute to retire its buses after 12 years or 500,000 miles. But perhaps the most pivotal moment of all, Casey recalls, was the decision to partner with the Chicago chapter of Volunteers strip out the old seats and grab bars from the next Fresh Moves bus so they can install grocery shelves. Image courtesy of Jane Sloss. Architecture for Humanity. Local Architecture for Humanity co-director Katherine Darnstadt, AIA, jokes that when she met with Pinzino and Casey, all they had to go on was “a bad PowerPoint.” The Chicago chapter agreed to take on the project pro-bono and put some of its best architects on the case. The team produced five designs incorporating everything from rooftop solar panels to a take-out window. The research and drawings they produced helped transform a vague idea into a tangible project. Now, Casey and Pinzino had a concept they would market to funders. Within six months, they had enough money (about $150,000) to get started. That’s “the power of being able to visualize an idea,” Darnstadt says. Without that design assistance, Casey doubts they would have been able to effectively communicate the concept and turn it into a reality. “At some point telling people, ‘I want a bus to go sell people fruits and vegetables,’ sounds like the craziest thing you’ve ever heard,” he says. “But not when you have a design.” The group was able to secure a bus from the CTA for the very reasonable price of $1. And, thanks to the simplicity of the chosen design, retrofitting cost just a few thousand dollars. That’s all organizational history now. May of last year saw the Fresh Moves bus take to the streets for the first time. Since then, Fresh Moves’ healthy wares have reached about 9,000 Chicagoans. Financial backers like Chase Bank and a handful of others help support the organization, which costs about $275,000 a year to operate. (Last year the bus brought in about $50,000 in sales.) Labor costs are relatively low. The organization employs four people: a bus mechanic and driver, a director, and two cashiers. Maintenance and gas costs represent a bigger portion of the budget, Casey says. Heading into its second year, Fresh Moves is planning to scale up. In August, the group received two additional buses from the CTA, plus a $45,000 grant from the USDA. They plan to expand further into the South Side. Recognition and replicability On a balmy day in August, Architecture for Humanity volunteers were hard at work unscrewing seats and removing grab bars in the two additional buses. Meanwhile, Susha McLeod, the driver, explained to a worker what adjustments were needed in the existing bus. Merideth Blake, an architecture graduate student at Chicago’s Archeworks alternative design school, was slinging a wrench as part of her orientation, alongside 10 of her classmates. The young woman was inspired to get into the field after a stint working for the city of Chicago and an assignment that involved mapping local neighborhoods. Working with the community is exactly what Blake wants out of her education and career. “It’s rewarding,” she says. “It offers you, as a student, a lot of insight.” By midday, the two buses were almost completely emptied, save for the back benches, the air conditioning units, and the driver’s seats, which will remain in the final design. Across the parking lot, a worker was cutting a new countertop, one with shelves, to provide extra storage space for Fresh Moves’ staff. Eventually, shelves made of woven steel will be installed, smaller at the top and deeper and larger at the floor. When customers are shopping, the counter for the register will fold down from the wall. Fresh Moves’ is gaining recognition. It was featured in Michelle Obama’s book, American Grown, as well as in Oprah magazine. Through Nov. 25, Fresh Moves’ concept will be at the center of the design world at the 2012 Venice Architecture Biennale, as part of the U.S. Pavilion’s exhibit Spontaneous Interventions: Design Actions for the Common Good. It’s also inspiring similar programs in Chattanooga, Tenn., and Kansas City, says Casey. “That’s one of best parts, of all of this,” he says, “It’s unbelievably replicable.” Selling themselves Solving the food access problem of hundreds of thousands of Chicagoans is a daunting task. But efforts like Fresh Moves’, as part of a larger community-wide strategy, seem to be making progress. A recent follow-up report to the 2006 “food desert” study found that roughly 40 percent fewer people in Chicago are living in food deserts since the initial report. If there’s a lesson here, Casey says, it’s that given a choice, healthier foods have a way of selling themselves. One of his proudest moments was a scene he witnessed on a street corner not far away, when an ice cream trucked pulled up behind the Fresh Moves bus. “There were two people at the ice cream truck,” he says, “and a line at the [Fresh Moves] bus.” Recent Related: RecoveryPark Offers Fresh Start for Detroit with Urban Farming AIA Chicago Small Project Awards Take a Walk Outside Back to AIArchitect November 16, 2012 Go to the current issue of AIArchitect