The Evolution of Homo Sapiens

advertisement

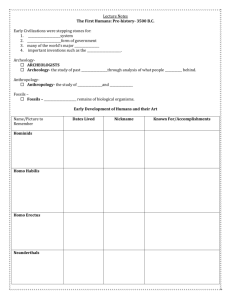

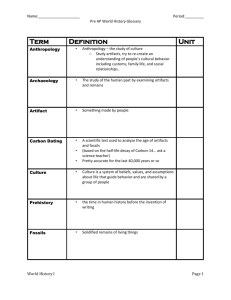

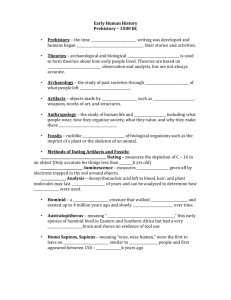

Ch. 1 – Before History Throughout the evening of 30 November 1974, a tape player in an Ethiopian desert blared the Beatles’ song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” at top volume. The site was an archaeological camp at Hadar, a remote spot about 320 kilometers (200 miles) northeast of Addis Ababa. The music helped fuel a spirited celebration: earlier in the day, archaeologists had discovered the skeleton of a woman who died 3.2 million years ago. Scholars refer to this woman’s skeleton as AL 288-1, but the woman herself has become by far the world’s bestknown prehistoric individual under the name Lucy. At the time of her death, from unknown causes, Lucy was twenty-five to thirty years of age. She stood just over 1 meter (about 3.5 feet) tall and probably weighed about 25 kilograms (55 pounds). After she died, sand and mud covered Lucy’s body, hardened gradually into rock, and entombed her remains. By 1974, however, rain waters had eroded the rock and exposed Lucy’s fossilized skeleton. The archaeological team working at Hadar eventually found 40 percent of Lucy’s bones, which together form one of the most complete and bestpreserved skeletons of any early human ancestor. Later searches at Hadar turned up bones belonging to perhaps as many as sixty-five additional individuals, although no other collection of bones rivals Lucy’s skeleton for completeness. Analysis of Lucy’s skeleton and other bones found at Hadar demonstrates that the earliest ancestors of modern human beings walked upright on two feet. Erect walking is crucial for human beings because it frees their arms and hands for other tasks. Lucy and her contemporaries did not possess large or well-developed brains—Lucy’s skull was about the size of a small grapefruit—but unlike the neighboring apes, which used their forelimbs for locomotion, Lucy and her companions could carry objects with their arms and manipulate tools with their dexterous hands. Those abilities enabled Lucy and her companions to survive better than many other species. As the brains of our human ancestors grew larger and more sophisticated—a process that occurred over a period of several million years—human beings learned to take even better advantage of their arms and hands and established flourishing communities throughout the world. According to geologists the earth came into being about 4.5 billion years ago. The first living organisms made their appearance hundreds of millions of years later. In their wake came increasingly complex creatures such as fish, birds, reptiles, and mammals. About forty million years ago, short, hairy, monkeylike animals began to populate tropical regions of the world. Humanlike cousins to these animals began to appear only four or five million years ago, and our own species, Homo sapiens, about two hundred thousand years ago. 5 Even the most sketchy review of the earth’s natural history clearly shows that human society has not developed in a vacuum. The earliest human beings inhabited a world already well stocked with flora and fauna, a world shaped for countless eons by natural rhythms that governed the behavior of all the earth’s creatures. Human beings made a place for themselves in this world, and over time they demonstrated remarkable ingenuity in devising ways to take advantage of the earth’s resources. Indeed, it has become clear in recent years that the human animal has exploited the natural environment so thoroughly that the earth has undergone irreversible changes. A discussion of such early times might seem peripheral to a book that deals with the history of human societies, their origins, development, and interactions. In conventional terminology, prehistory refers to the period before writing, and history refers to the era after the invention of writing enabled human communities to record and store information. It is certainty true that the availability of written documents vastly enhances the ability of scholars to understand past ages, but recent research by archaeologists and evolutionary biologists has brightly illuminated the physical and social development of early human beings. It is now clear that long before the invention of writing, human beings made a place for their species in the natural world and laid the social, economic, and cultural foundations on which their successors built increasingly complex societies. The Evolution of Homo Sapiens During the past century or so, archaeologists, evolutionary biologists, and other scholars have vastly increased the understanding of human origins and the lives our distant ancestors led. Their work has done much to clarify the relationship between human beings and other animal species. On one hand, researchers have shown that human beings share some remarkable similarities with the large apes. This point is true not only of external features, such as physical form, but also of the basic elements of genetic makeup and body chemistry—DNA, chromosomal patterns, life-sustaining proteins, and blood types. In the case of some of these elements, scientists have been able to observe a difference of only 1.6 percent between the DNA of human beings and chimpanzees. Biologists therefore place human beings in the order of primates, along with monkeys, chimpanzees, gorillas, and the various other large apes. On the other hand, human beings clearly stand out as the most distinctive of the primate species. Small differences in genetic makeup and body chemistry have led to enormous differences in levels of intelligence and ability to exercise control over the natural world. Human beings developed an extraordinarily high order of intelligence, which enabled them to devise tools, technologies, language skills, and other means ofcommunication and cooperation. Whereas other animal species adapted physically and genetically to their natural environment, human beings altered the natural environment to suit their own needs and desires—a process that began in remote prehistory and continues in the present day. Over the long run, too, intelligence endowed humans with immense potential for social and cultural development. The Hominids A series of spectacular discoveries in east Africa has thrown valuable light on the evolution of the human species. In Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, and other places, archaeologists have unearthed bones and tools of human ancestors going back about five million years. The Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania and Hadar in Ethiopia have yielded especially 6 rich remains of individuals like the famous Lucy. These individuals probably represented several different species belonging to the genus Australopithecus (“the southern ape”), which flourished in east Africa during the long period from about four million to one million years ago. In spite of its name, Australopithecus was not an ape but rather a hominid—a creature belonging to the family Hominidae, which includes human and humanlike species. Evolutionary biologists recognize Australopithecus as a genus standing alongside Homo (the genus in which biologists place modern human beings) in the family of hominids. Compared to our own species, Homo sapiens, Lucy and other australopithecines would seem short, hairy, and limited in intelligence. They stood something over one meter (three feet) tall, weighed 25 to 55 kilograms (55 to 121 pounds), and had a brain size of about 500 cubic centimeters. (The brain size of modern humans averages about 1,400 cc.) Fossilized footprints preserved near Olduvai Gorge in modern Tanzania show that hominids walked upright some 3.5 million years ago. These prints came from an adult walking on the right and a child on the left. Compared with other ape and animal species, however, australopithecines were sophisticated creatures. They walked upright on two legs, which enabled them to use their arms independently for other tasks. They had well-developed hands with opposable thumbs, which enabled them to grasp tools and perform intricate operations. They almost certainly had some ability to communicate verbally, although analysis of their skulls suggests that the portion of the brain responsible for speech was not very large or well developed. The intelligence of australopithecines was sufficient to allow them to plan complex ventures. They often traveled deliberately—over distances of 15 kilometers (9.3 miles) and more—to obtain the particular kinds of stone that they needed to fashion tools. Chemical analyses show that the stone from which australopithecines made tools was often available only at sites distant from the camps where archaeologists discovered the finished tools. Those tools included choppers, scrapers, and other implements for food preparation. With the aid of their tools and intelligence, australopithecines established themselves securely throughout most of eastern and southern Africa. By about one million years ago, australopithecines had disappeared as new species of hominids possessing greater intelligence evolved and displaced their predecessors. The new species belonged to the genus Homo and thus represented creatures considerably different from the australopithecines. Most important of them was Homo erectus—“ upright-walking human”—who flourished from about two million to 200,000 years ago. Homo erectus possessed a larger brain than the australopithecines—the average capacity was about 1,000 cc—and fashioned more sophisticated tools as well. 7 To the australopithecine choppers and scrapers, Homo erectus added cleavers and hand axes, which not only were useful in hunting and food preparation but also provided protection against predators. Homo erectus also knew how to tend a fire, which furnished the species with a means to cook food, a defense against large animals, and a source of artificial heat. Even more important than tools and fire were intelligence and language skills, which enabled individuals to communicate complex ideas to one another. Archaeologists have determined, for example, that bands of Homo erectus men conducted their hunts in well-coordinated ways that presumed prior communication. Many sites 8 associated with Homo erectus served as camps for communities of hunters. The quantities of animal remains found at those sites—particularly bones of large and dangerous animals such as elephant, rhinoceros, and bear—provide evidence that hunters worked in groups and brought their prey back to their camps. Cooperation of this sort presumed both high intelligence and effective language skills. With effective tools, fire, intelligence, and language, Homo erectus gained increasing control over the natural environment and introduced the human species into widely scattered regions. Whereas australopithecines had not ventured beyond eastern and southern Africa, Homo erectus migrated to north Africa and the Eurasian 9 landmass. Almost two million years ago, Homo erectus groups moved to southwest Asia and beyond to Europe, south Asia, east Asia, and southeast Asia. By two hundred thousand years ago they had established themselves throughout the temperate zones of the eastern hemisphere, where archaeologists have unearthed many specimens of their bones and tools. Homo Sapiens Like Australopithecus, though, Homo erectus faded with the arrival of more intelligent and successful human species. Homo sapiens (“consciously thinking human”) evolved about two hundred thousand years ago and has skillfully adapted to the natural environment ever since. Early Homo sapiens already possessed a large brain—one approaching the size of modern human brains. More important than the size of the brain, though, is its structure: the modern human brain is especially well developed in the frontal regions, where conscious and reflective thought takes place. This physical feature provided Homo sapiens with an enormous advantage. Although not endowed with great strength and not equipped with natural means of attack and defense— claws, beaks, fangs, shells, venom, and the like—Homo sapiens possessed a remarkable intelligence that provided a powerful edge in the contest for survival. It enabled individuals to understand the structure of the world around them, to organize more efficient methods of exploiting natural resources, and to communicate and cooperate on increasingly complex tasks. Intelligence enabled Homo sapiens to adapt to widely varying environmental conditions and to establish the species securely throughout the world. Beginning about one hundred thousand years ago, communities of Homo sapiens spread throughout the eastern hemisphere and populated the temperate lands of Africa, Europe, and Asia, where they encountered Homo erectus groups that had inhabited those regions for several hundred thousand years. Homo sapiens soon moved beyond the temperate zones, though, and established communities in progressively colder regions—migrations that were possible because their intelligence allowed Homo sapiens to fashion warm clothes from animal skins and to build effective shelters against the cold. Between sixty thousand and fifteen thousand years ago, Homo sapiens extended the range of human population even further. Several ice ages cooled the earth’s temperature during that period, resulting in the concentration of water in massive glaciers, the lowering of the world’s sea levels, and the exposure of land bridges that linked Asia with regions of the world previously uninhabited by humans. Small bands of individuals crossed those bridges and established communities in the islands of Indonesia and New Guinea, and some of them went farther to cross the temporarily narrow straits of water separating southeast Asia from Australia. Homo sapiens arrived in Australia about sixty thousand years ago, perhaps even earlier. Somewhat later, beginning as early perhaps as twenty-five thousand years ago, other groups took advantage of land bridges linking Siberia with Alaska and established human communities in North America. From there they migrated throughout the western hemisphere. About fifteen thousand years ago, communities of Homo sapiens had appeared in almost every habitable region of the world. Their intellectual abilities enabled members of the Homo sapiens species to recognize problems and possibilities in their environment and then to take action that favored their survival. At sites of early settlements, archaeologists have discovered increasingly sophisticated tools that reflect Homo sapiens’ progressive control over the environment. In addition to the choppers, scrapers, axes, and other tools that earlier species possessed, Homo sapiens used knives, spears, bows, and arrows. Individuals 10 made dwellings for themselves in caves and in hutlike shelters fabricated from wood, bones, and animal skins. In cold regions Homo sapiens warmed themselves with fire and cloaked themselves in the skins of animals. Mounds of ashes discovered at their campsites show that in especially cold regions, they kept fires burning continuously during the winter months. In all parts of the earth, members of the species learned to use spoken languages to communicate complex ideas and coordinate their efforts in the common interest. Homo sapiens used superior intelligence, sophisticated tools, and language to exploit the natural world more efficiently than any other species the earth had seen. 11 Indeed, intelligent, tool-bearing humans competed so successfully in the natural world that they brought tremendous pressure to bear on other species. As the population of Homo sapiens increased, large mammal species in several parts of the world became extinct. Mammoths and the woolly rhinoceros disappeared from Europe, giant kangaroos from Australia, and mammoths, mastodons, and horses from the Americas. Archaeologists believe that changes in the earth’s climate might have altered the natural environment enough to harm those species. In most cases, however, human hunting probably helped push large animals into extinction. Thus, from their earliest days on earth, members of the species Homo sapiens became effective and efficient competitors in the natural world—to the point that they threatened the very survival of other large but less intelligent species. Paleolithic Society By far the longest portion of the human experience on earth is the period historians and archaeologists call the paleolithic era, the “old stone age.” The principal characteristic of the paleolithic era was that human beings foraged for their food: they hunted wild animals or gathered edible products of naturally growing plants. The paleolithic era extended from the evolution of the first hominids until about twelve thousand years ago, when groups of Homo sapiens in several parts of the world began to rely on cultivated crops to feed themselves. Economy and Society of Hunting and Gathering Peoples In the absence of written records, scholars have drawn inferences about paleolithic economy and society from other kinds of evidence. Archaeologists have excavated many sites that open windows on paleolithic life, and anthropologists have carefully studied hunting and gathering societies in the contemporary world. In the Amazon basin of South America, the tropical forests of Africa and southeast Asia, the deserts of Africa and Australia, and a few other regions as well, small communities of hunters and gatherers follow the ways of our common paleolithic ancestors. Although contemporary hunting and gathering communities reflect the influence of the modern world— they are by no means exact replicas of paleolithic societies—they throw important light on the economic and social dynamics that shaped the experiences of prehistoric foragers. In combination, then, the studies of both archaeologists and anthropologists help to illustrate how the hunting and gathering economy decisively influenced all dimensions of the human experience during the paleolithic era. A hunting and gathering economy virtually prevents individuals from accumulating private property and basing social distinctions on wealth. To survive, most hunters and gatherers must follow the animals that they stalk, and they must move with the seasons in search of edible plant life. Given their mobility, it is easy to see that for them, the notion of private, landed property has no meaning at all. Individuals possess only a few small items such as weapons and tools that they can carry easily as they move. In the absence of accumulated wealth, hunters and gatherers of paleolithic times, like their contemporary descendants, probably lived a relatively egalitarian existence. Social distinctions no doubt arose, and some individuals became influential because of their age, strength, courage, intelligence, fertility, force of personality, or some other trait. But personal or family wealth could not have served as a basis for permanent social differences. Some scholars believe that this relative social equality in paleolithic times extended even further, to relations between the sexes. All members of a paleolithic group made 12 important contributions to the survival of the community. Men traveled on sometimes distant hunting expeditions in search of large animals while women and children gathered edible plants, roots, nuts, and fruits from the area near the group’s camp. Meat from the hunt was the most highly prized item in the paleolithic diet, but plant foods were essential to survival. Anthropologists calculate that in modern hunting and gathering societies, women contribute more calories to the community’s diet than do the men. As a source of protein, meat represents a crucial supplement to the diet. But plant products sustain the men during hunting expeditions and feed the entire community when the hunt does not succeed. Because of the thorough interdependence of the sexes from the viewpoint of food production, paleolithic society probably did not encourage the domination of one sex by the other—certainly not to the extent that became common later. Artist’s conception of food preparation in a Homo erectus community. A hunting and gathering economy has implications not only for social and sexual relations but also for community size and organization. The foraging lifestyle of hunters and gatherers dictates that they mostly live in small bands, which today include about thirty to fifty members. Larger groups could not move efficiently or find enough food to survive over a long period. During times of drought or famine, even small bands have trouble providing for themselves. Individual bands certainly have relationships with their neighbors—agreements concerning the territories that the groups exploit, for example, or arrangements to take marriage partners from each others’ groups—but the immediate community is the focus of social life. The survival of hunting and gathering bands depends on a sophisticated understanding of their natural environment. In contemporary studies, anthropologists have found that hunting and gathering peoples do not wander aimlessly about hoping to find a bit of food. Instead, they exploit the environment systematically and efficiently by timing their movements to coincide with the seasonal migrations of the animals they hunt and the life cycles of the plant species they gather. Archaeological remains show that early peoples also went about hunting and gathering in a purposeful and intelligent manner. As early as three hundred thousand years ago, for example, Homo erectus had learned to hunt big game successfully. Although almost anyone could take a small, young, or wounded animal, the hunting of big game 13 posed difficult problems. Large animals such as elephant, mastodon, rhinoceros, bison, and wild cattle were not only strong and fast but also well equipped to defend themselves and even attack their human hunters. Homo erectus and Homo sapiens fashioned special tools, such as sharp knives, spears, and bows and arrows, and devised special tactics for hunting these animals. The hunters wore disguises such as animal skins and coordinated their movements so as to attack game simultaneously from several directions. They sometimes even started fires or caused disturbances to stampede herds into swamps or enclosed areas where hunters could kill them more easily. Paleolithic hunting was a complicated venture. It clearly demonstrated the capacity of early human communities to pool their uniquely human traits—high intelligence, ability to make complicated plans, and sophisticated language and communications skills—to exploit the environment. In regions where food resources were especially rich, a few peoples in late paleolithic times abandoned the nomadic lifestyle and established permanent settlements. The most prominent paleolithic settlements were those of Natufian society in the eastern Mediterranean (modern-day Israel and Lebanon), Jomon society in central Japan, and Chinook society in the Pacific northwest region of North America (including the modern states of Oregon and Washington and the Canadian province of British Columbia). As early as 13,500 B.C.E., Natufians collected wild wheat and took animals from abundant antelope herds. From 10,000 to 300 B.C.E., Jomon settlers harvested wild buckwheat and developed a productive fishing economy. Chinook society emerged after 3000 B.C.E. and flourished until the mid-nineteenth century C.E., principally on the basis of wild berries, acorns, and massive salmon runs in local rivers. Paleolithic settlements had permanent dwellings, sometimes in the form of long houses that accommodated several hundred people, but often in the form of smaller structures for individual families. Many settlements had populations of a thousand or more individuals. As archaeological excavations continue, it is becoming increasingly clear that paleolithic peoples organized complex societies with specialized rulers and craftsmen in many regions where they found abundant food resources. Statue of a Neandertal man based on the study of recently discovered bones. Paleolithic Culture Paleolithic individuals did not limit their creative thinking to strictly practical matters of subsistence and survival. Instead, they reflected on the nature of human existence and the world around them. The earliest evidence of reflective thought comes from sites associated with Neandertal peoples, named after the Neander valley in western Germany where their remains first came to light. Neandertal peoples flourished in Europe and 14 southwest Asia between about two hundred thousand and thirty-five thousand years ago. Most scholars regard Neandertal peoples as members of a distinct human species known as Homo neandertalensis. For about ten millennia, from forty-five thousand to thirty-five thousand years ago, Neandertal groups inhabited some of the same regions as Homo sapiens communities, and members of the two species sometimes lived in close proximity to one another. DNA analysis suggests that there was little if any interbreeding between the two species, but it is quite likely that individuals traded goods between their groups, and it is possible that Neandertal peoples imitated the technologies and crafts of their more intelligent cousins. At several Neandertal sites archaeologists have discovered signs of careful, deliberate burial accompanied by ritual observances. Perhaps the most notable is that of Shanidar cave, located about 400 kilometers (250 miles) north of Baghdad in modernday Iraq, where survivors laid the deceased to rest on beds of freshly picked wild flowers and then covered the bodies with shrouds and garlands of other flowers. At other Neandertal sites in France, Italy, and central Asia, survivors placed flint tools and animal bones in and around the graves of the deceased. It is impossible to know precisely what Neandertal peoples were thinking when they buried their dead in that fashion. Possibly they simply wanted to honor the memory of the departed, or perhaps they wanted to prepare the dead for a new dimension of existence, a life beyond the grave. Whatever their intentions, Neandertal peoples apparently recognized a significance in the life and death of individuals that none of their ancestors had appreciated. They had developed a capacity for emotions and feelings, and they cared for one another even to the extent of preparing elaborate resting places for the departed. Homo sapiens was much more intellectually inventive and creative than Homo neandertalensis. Many scholars argue that Homo sapiens owed much of the species’s intellectual prowess to human beings’ ability to construct powerful and flexible languages for the communication of complex ideas. With the development of languages, human beings were able both to accumulate knowledge and to transmit it precisely and efficiently to new generations. Thus it was not necessary for every individual human being to learn from trial and error or from direct personal experience about the nature of the local environment or the best techniques for making advanced tools. Rather, it was possible for human groups to pass large and complex bodies of information along to their offspring, who then were able to make immediate use of it and furthermore were in a good position to build on inherited information by devising increasingly effective ways of satisfying human needs and desires. Sewing needles fashioned from animal bones about fifteen thousand years ago. From its earliest days on the earth, Homo sapiens distinguished itself as a creative species. At least 200,000 years ago, Homo sapiens was producing stone blades with long cutting edges. By 140,000 years ago early humans had learned to supplement their diet with shellfish from coastal waters, and they had developed networks with neighbors that enabled them to trade high-quality obsidian stone over distances sometimes exceeding 300 kilometers (185 miles). By 110,000 years ago they had devised means of catching fish from deep waters. By 100,000 years ago they had begun to fashion sharp tools such as sewing 15 needles and barbed harpoons out of animal bones. Somewhat later they invented spear-throwers—small slings that enaabled hunters to hurl spears at speeds upwards of 160 kilometers per hour (100 miles per hour). About 40,000 to 50,000 years ago, they were fabricating ornamental beads, necklaces, and bracelets, and shortly thereafter they began painting images of human and animal subjects. About 10,000 years ago, they invented the bow and arrow, a weapon that dramatically enhanced the power of human beings with respect to other animal species. The most visually impressive creations of early Homo sapiens are the Venis figurines and cave paintings found at many sites of early human habitation. Archaeologists use the term Venus figurines—named after the Roman goddess of love—to refer to small sculptures of women, usually depicted with exaggerated sexual features. Most scholars believe that the figures reflect a deep interest in fertility. The prominent sexual features of the Venus figurines suggest that the sculptors’ principal interests were fecundity and the generation of new life—matters of immediate concern to paleolithic societies. Some interpreters speculate that the figures had a place in ritual observances intended to increase fertility. Venus figurine from Austria. The exaggerated sexual features suggest that paleolithic peoples fashioned such figurines out of an interest in fertility. This sculpture was produced between 24,000 and 22,000 B.C.E. Paintings in caves frequented by early humans are the most dramatic examples of prehistoric art. The known examples of cave art date from about thirty-four thousand to twelve thousand years ago, and most of them come from caves in southern France and northern Spain. In that region alone, archaeologists have discovered more than one hundred caves bearing prehistoric paintings. The best-known are Lascaux in France and Altamira in Spain. There prehistoric peoples left depictions of remarkable sensitivity and power. Most of the subjects were animals, especially large game such as mammoth, bison, and reindeer, although a few human figures also appear. As in the case of the Venus figurines, the explanation for the cave paintings involves a certain amount of educated guesswork. It is conceivable that early artists sometimes worked for purely aesthetic reasons—to beautify their living quarters. But many examples of cave art occur in places that are almost inaccessible to human beings—deep within remote chambers, for example, or at the end of long and constricted passages. Paintings in such remote locations presumably had some other purpose. Most analysts believe that the prominence of game animals in the paintings reflects the artists’ interest in successful hunting expeditions. Thus cave paintings may have represented efforts 16 to exercise “sympathetic magic”—to gain control over subjects (in this case, game animals) by capturing their spirits (by way of accurate representations of their physical forms). Although not universally accepted, this interpretation accounts reasonably well for a great deal of the evidence and has won widespread support among scholars. Whatever the explanation for prehistoric art, the production of the works themselves represented conscious and purposeful activity of a high order. Early artists compounded their own pigments and manufactured their own tools. They made paints from minerals, plants, blood, saliva, water, animal fat, and other available ingredients. They used mortar and pestle for grinding pigments and mixing paints, which they applied with moss, frayed twigs and branches, or primitive brushes fabricated from hair. The simplicity and power of their representations have left deep impressions on modern critics ever since the early twentieth century, when their works became widely known. The display of prehistoric artistic talent clearly testifies once again to the remarkable intellectual power of the human species. Cave painting from Lascaux in southern France, perhaps intended to help hunters gain control over the spirits of large game animals. The Neolithic Era and the Transition to Agriculture A few societies of hunting and gathering peoples inhabit the contemporary world, although most of them do not thrive because agricultural and industrial societies have taken over environments best suited to a foraging economy. Demographers estimate the current number of hunters and gatherers to be about thirty thousand, a tiny fraction of the world’s human population of more than six billion. The vast majority of the world’s peoples, however, have crossed an economic threshold of immense significance. When human beings brought plants under cultivation and animals under domestication, they dramatically altered the natural world and steered human societies in new directions. 17 The Origins of Agriculture The term neolithic era means “new stone age,” as opposed to the old stone age of paleolithic times. Archaeologists first used the term neolithic because of refinements in tool-making techniques: they found polished stone tools in neolithic sites, rather than the chipped implements characteristic of paleolithic sites. Gradually, however, archaeologists became aware that something more fundamental than tool production distinguished the paleolithic from the neolithic era. Polished stone tools occurred in sites where peoples relied on cultivation, rather than foraging, for their subsistence. Today the term neolithic era refers to the early stages of agricultural society, from about twelve thousand to six thousand years ago. Because they depended on the bounty of nature, foraging peoples faced serious risks. Drought, famine, disease, floods, extreme temperatures, and other natural disasters could annihilate entire communities. Even in good times, many hunting and gathering peoples had to limit their populations so as not to exceed the capacity of their lands to support them. They most likely resorted routinely to infanticide to control their numbers. Neolithic peoples sought to ensure themselves of more regular food supplies by encouraging the growth of edible crops and bringing wild animals into dependence on human keepers. Many scholars believe that women most likely began the systematic care of plants. As the principal gatherers in foraging communities, women became familiar with the life cycles of plants and noticed the effects of sunshine, rain, and temperature on vegetation. Hoping for larger and more reliable supplies of food, women in neolithic societies probably began to nurture plants instead of simply collecting available foods in the wild. Meanwhile, instead of just stalking game with the intention of killing it for meat, neolithic men began to capture animals and domesticate them by providing for their needs and supervising their breeding. Over a period of decades and centuries, those practices gradually led to the formation of agricultural economies. By suggesting that agriculture brought about an immediate transformation of human society, the popular term agricultural revolution is somewhat misleading. Two cave paintings produced five to six thousand years ago illustrate the different roles played by men and women in the early days of agriculture. Here women harvest grain. 18 Men herd domesticated cattle in the early days of agriculture. This painting and the previous one both came from a cave at Tassili n’Ajjer in modern-day Algeria. The establishment of an agricultural economy was not an event that took place at a given date but, rather, a process that unfolded over many centuries, as human beings gradually learned how to cultivate crops and keep animals. It would be more appropriate to speak of an “agricultural transition”—leading from paleolithic experiments with cultivation to early agricultural societies in the neolithic era—rather than an agricultural revolution. Agriculture—including both the cultivation of crops and the domestication of animals— emerged independently in several different parts of the world. The earliest evidence of agricultural activity discovered so far dates to the era after 9000 B.C.E., when peoples of southwest Asia (modern-day Iraq, Syria, and Turkey) cultivated wheat and barley while domesticating sheep, goats, pigs, and cattle. Between 9000 and 7000 B.C.E., African peoples inhabiting the southeastern margin of the Sahara desert (modern-day Sudan) domesticated cattle, sheep, and goats while cultivating sorghum. Between 8000 and 6000 B.C.E., peoples of sub-Saharan west Africa (in the vicinity of modern Nigeria) also began independently to cultivate yams, okra, and black-eyed peas. In east Asia, residents of the Yangzi River valley began to cultivate rice as early as 6500 B.C.E., and their neighbors to the north in the Yellow River valley raised crops of millet and soybeans after 5500 B.C.E. East Asian peoples also kept pigs and chickens from an early date, perhaps 6000 B.C.E., and they later added water buffaloes to their domesticated stock. In southeast Asia the cultivation of taro, yams, coconut, breadfruit, bananas, and citrus fruits, including oranges, lemons, limes, tangerines, and grapefruit, dates from an indeterminate but very early time, probably 3000 B.C.E. or earlier. Peoples of the western hemisphere also turned independently to agriculture. Inhabitants of Mesoamerica (central Mexico) cultivated maize (corn) as early as 4000 B.C.E., and they later added a range of additional food crops, including beans, peppers, squashes, and tomatoes. Residents of the central Andean region of South America (modern Peru) cultivated potatoes after 3000 B.C.E., and they later added maize and beans to their diets. It is possible that the Amazon River valley was yet another site of independently invented agriculture, this one centering on the cultivation of manioc, sweet potatoes, and peanuts. Domesticated animals were much less prominent in the Americas than in the eastern 19 hemisphere. Paleolithic peoples had hunted many large species to extinction: mammoths, mastodons, and horses had all disappeared from the Americas by 7000 B.C.E. (The horses that have figured so prominently in the modern history of the Americas all descended from animals introduced to the western hemisphere during the past five hundred years.) With the exception of llamas, alpacas, and guinea pigs of the Andean regions, most other American animals were not well suited to domestication. Once established, agriculture spread rapidly, partly because of the methods of early cultivators. One of the earliest techniques, known as slash-and-burn cultivation, involved frequent movement on the part of farmers. To prepare a field for cultivation, a 20 community would slash the bark on a stand of trees in a forest and later burn the dead trees to the ground. The resulting weed-free patch was extremely fertile and produced abundant harvests. After a few years, however, weeds invaded the field, and the soil lost its original fertility. The community then moved to another forest region and repeated the procedure. Migrations of slash-and-burn cultivators helped spread agriculture throughout both eastern and western hemispheres. By 6000 B.C.E., for example, agriculture had spread from its southwest Asian homeland to the eastern shores of the Mediterranean and the Balkan region of eastern Europe, and by 4000 B.C.E. it had spread farther to western Europe north of the Mediterranean. 21 While agriculture radiated out from its various hearths, foods originally cultivated in only one region also spread widely, as merchants, migrants, or other travelers carried knowledge of those foods to agricultural lands that previously had relied on different crops. Wheat, for example, spread from its original homeland in southwest Asia to Iran and northern India after 5000 B.C.E. and farther to northern China perhaps by 3000 B.C.E. Meanwhile, rice spread from southern China to southeast Asia by 3000 B.C.E. and to the Ganges River valley in India by 1500 B.C.E. African sorghum reached India by 2000 B.C.E., while southeast Asian bananas took root in tropical lands throughout the Indian Ocean basin. In the western hemisphere, maize spread from Mesoamerica to the southwestern part of the United States by 1200 B.C.E. and farther to the eastern woodlands region of North America by 100 C.E. Agriculture involved long hours of hard physical labor—clearing land, preparing fields, planting seeds, pulling weeds, and harvesting crops. Indeed, agriculture probably required more work than paleolithic foraging: anthropologists calculate that modern hunting and gathering peoples spend about four hours per day in providing themselves with food and other necessities, devoting the remainder of their time to rest, leisure, and social activities. Yet agriculture had its own appeal in that it made possible the production of abundant food supplies. Thus agriculture spread widely, eventually influencing the lives and experience of almost all human beings. Early Agricultural Society In the wake of agriculture came a series of social and cultural changes that transformed human history. Perhaps the most important change associated with agriculture was a population explosion. Spread thinly across the earth in paleolithic times, the human species multiplied prodigiously after agriculture increased the supply of food. Historians estimate that before agriculture, about 10,000 B.C.E., the earth’s human population was about four million. By 5000 B.C.E., when agriculture had appeared in a few world regions, human population had risen to about five million. Estimates for later dates demonstrate eloquently the speed with which, thanks to agriculture, human numbers increased: Year Human Population 3000 B.C.E. 14 million 2000 B.C.E. 27 million 1000 B.C.E. 50 million 500 B.C.E. 100 million Their agricultural economy and rapidly increasing numbers encouraged neolithic peoples to adopt new forms of social organization. Because they devoted their time to cultivation rather than foraging, neolithic peoples did not continue the migratory life of their paleolithic predecessors but, rather, settled near their fields in permanent villages. One of the earliest known neolithic villages was Jericho, site of a freshwater oasis north of the Dead Sea in present-day Israel, which came into existence before 8000 B.C.E. Even in its early days, Jericho may have had two thousand residents—a vast crowd compared with a paleolithic hunting band. The residents farmed mostly wheat and barley with the aid of water from the oasis. During the earliest days of the settlement, they kept no domesticated animals, but they added meat to their diet by hunting local game animals. They also engaged in a limited amount of trade, particularly in salt and obsidian, a hard, volcanic glass from which ancient peoples fashioned knives and blades. About 7000 B.C.E., the residents surrounded their circular mud huts with a 22 formidable wall and moat—a sure sign that the wealth concentrated at Jericho had begun to attract the interest of human predators. The concentration of large numbers of people in villages encouraged specialization of labor. Most people in neolithic villages cultivated crops or kept animals. Many also continued to hunt and forage for wild plants. But a surplus of food enabled some individuals to concentrate their time and talents on enterprises that had nothing to do with the production of food. The rapid development of specialized labor is apparent from excavations carried out at one of the best-known neolithic settlements, Çatal Hüyük. Located in south-central Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), Çatal Hüyük was occupied continuously from 7250 to 5400 B.C.E., when residents abandoned the site. Originally a small and undistinguished neolithic village, Çatal Hüyük grew into a bustling town, accommodating about five thousand inhabitants. Archaeologists have uncovered evidence that residents manufactured pots, baskets, textiles, leather, stone and metal tools, wood carvings, carpets, beads, and jewelry among other products. Çatal Hüyük became a prominent village partly because of its close proximity to large obsidian deposits. The village probably was a center of production and trade in obsidian tools: archaeologists have discovered obsidian that originated near Çatal Hüyük at sites throughout much of the eastern Mediterranean region. Three early craft industries—pottery, metallurgy, and textile production—illustrate the potential of specialized labor in neolithic times. Neolithic craftsmen were not always the original inventors of the technologies behind those industries: the Jomon society of central Japan produced the world’s first known pottery, for example, about 10,000 B.C.E. But neolithic craftsmen expanded dramatically on existing practices and supplemented them with new techniques to fashion natural products into useful items. Their enterprises reflected the conditions of early agricultural society: either the craft industries provided tools and utensils needed by cultivators, or they made use of cultivators’ and herders’ products in new ways. The earliest of the three craft industries to emerge was pottery. Paleolithic hunters and gatherers had no use for pots. They did not store food for long periods of time, and in any case lugging heavy clay pots around as they moved from one site to another would have been inconvenient. A food-producing society, however, needs containers to store surplus foods. By about 7000 B.C.E. neolithic villagers in several parts of the world had discovered processes that transformed malleable clay into permanent, fire-hardened, waterproof pottery capable of storing dry or liquid products. Soon thereafter, neolithic craftsmen discovered that they could etch designs into their clay that fire would harden into permanent decorations and furthermore that they could color their products with glazes. As a result, pottery became a medium of artistic expression as well as a source of practical utensils. Pottery vessel from Haçilar in Anatolia in the shape of a reclining deer, produced about the early sixth millennium B.C.E. Metallurgy soon joined pottery as a neolithic industry. The earliest metal that humans worked with systematically was copper. In many regions of the world, copper occurs 23 naturally in relatively pure and easily malleable form. By hammering the cold metal it was possible to turn it into jewelry and simple tools. By 6000 B.C.E., though, neolithic villagers had discovered that when heated to high temperatures, copper became much more workable and that they could use heat to extract copper from its ores. By 5000 B.C.E., they had raised temperatures in their furnaces high enough to melt copper and pour it into molds. With the technology of smelting and casting copper, neolithic communities were able to make not only jewelry and decorative items but also tools such as knives, axes, hoes, and weapons. Moreover, copper metallurgy served as a technological foundation on which later neolithic craftsmen developed expertise in the working of gold, bronze, iron, and other metals. Because natural fibers decay more easily than pottery or copper, the dating of textile production is not certain, but fragments of textiles survive from as early as 6000 B.C.E. As soon as they began to raise crops and keep animals, neolithic peoples experimented with techniques of selective breeding. Before long they had bred strains of plants and animals that provided long, lustrous, easily worked fibers. They then developed technologies for spinning the fibers into threads and weaving the threads into cloth. The invention of textiles was probably the work of women, who were able to spin thread and weave fabrics at home while nursing and watching over small children. In any case, textile production quickly became one of the most important enterprises in agricultural society. The concentration of people into permanent settlements and the increasing specialization of labor provided the first opportunity for individuals to accumulate considerable wealth. Individuals could trade surplus food or manufactured products for gems, jewelry, and other valuable items. The institutionalization of privately owned landed property—which occurred at an uncertain date after the introduction of agriculture— enhanced the significance of accumulated wealth. Because land was (and remains) the ultimate source of wealth in any agricultural society, ownership of land carried enormous economic power. When especially successful individuals managed to consolidate wealth in their families’ hands and kept it there for several generations, clearly defined social classes emerged. Already at Çatal Hüyük, for example, differences in wealth and social status are clear from the quality of interior decorations in houses and the value of goods buried with individuals from different social classes. Neolithic Culture Quite apart from its social effects, agriculture left its mark on the cultural dimension of the human experience. Because their lives and communities depended on the successful cultivation of crops, neolithic farmers closely observed the natural world around them and noted the conditions that favored successful harvests. In other words, they developed a kind of early applied science. From experience accumulated over the generations, they acquired an impressive working knowledge of the earth and its rhythms. Agricultural peoples had to learn when changes of season would take place: survival depended upon the ability to predict when they could reasonably expect sunshine, rain, warmth, and freezing temperatures. They learned to associate the seasons with the different positions of the sun, moon, and stars. As a result, they accumulated a store of knowledge concerning relationships between the heavens and the earth, and they made the first steps toward the elaboration of a calendar, which would enable them to predict with tolerable accuracy the kind of weather they could expect at various times of the year. The workings of the natural world also influenced neolithic religion. Paleolithic communities had already honored, and perhaps even worshiped, Venus figurines in 24 hopes of ensuring fertility. Neolithic religion reflected the same interest in fertility, but it celebrated particularly the rhythms that governed agricultural society—birth, growth, death, and regenerated life. Archaeologists have unearthed thousands of neolithic representations of gods and goddesses in the form of clay figurines, drawings on pots and vases, decorations on tools, and ritual objects. The neolithic gods included not only the life-bearing, Venus-type figures of paleolithic times but also other deities associated with the cycle of life, death, and regeneration. A pregnant goddess of vegetation, for example, represented neolithic hopes for fertility in the fields. Sometimes neolithic worshipers associated these goddesses with animals such as frogs or butterflies that dramatically changed form during the course of their lives, just as seeds of grain sprouted, flourished, died, and produced new seed for another agricultural cycle. Meanwhile, young male gods associated with bulls and goats represented the energy and virility that participates in the creation of life. Some deities were associated with death: many neolithic goddesses possessed the power to bring about decay and destruction. Yet physical death was not an absolute end. The procreative capacities of gods and goddesses resulted in the births of infant deities who represented the regeneration of life—freshly sprouted crops, replenished stocks of domestic animals, and infant human beings to inaugurate a new biological cycle. Thus neolithic religious thought clearly reflected the natural world of early agricultural society. The Origins of Urban Life Within four thousand years of its introduction, agriculture had dramatically transformed the face of the earth. Human beings multiplied prodigiously, congregated in densely populated quarters, placed the surrounding lands under cultivation, and domesticated several species of animals. Besides altering the physical appearance of the earth, agriculture also transformed the lives of human beings. Even a modest neolithic village dwarfed a paleolithic band of a few dozen hunters and gatherers. In larger villages and towns, such as Jericho and Çatal Hüyük, with their populations of several thousand people, their specialized labor, and their craft industries, social relationships became more complex than would have been conceivable during paleolithic times. Gradually, dense populations, specialized labor, and complex social relations gave rise to an altogether new form of social organization—the city. Like the transition from foraging to agricultural society, the development of cities and complex societies organized around urban centers was a gradual process rather than a well-defined event. Because of favorable location, some neolithic villages and towns attracted more people and grew larger than others. Over time, some of those settlements evolved into cities. What distinguished early cities from their predecessors, the neolithic villages and towns? Even in their early days, cities differed from neolithic villages and towns in two principal ways. In the first place, cities were larger and more complex than neolithic villages and towns. Çatal Hüyük featured an impressive variety of specialized crafts and industries. With progressively larger populations, cities fostered more intense specialization than any of their predecessors among the neolithic villages and towns. Thus it was in cities that large classes of professionals emerged—individuals who devoted all their time to efforts other than the production of food. Professional craft workers refined existing technologies, invented new ones, and raised levels of quality and production. Professional managers also appeared—governors, administrators, military strategists, tax collectors, and the like—whose services were necessary to the survival of the community. Cities also gave rise to professional cultural specialists such as 25 priests, who maintained their communities’ traditions, transmitted their values, organized public rituals, and sought to discover meaning in human existence. In the second place, whereas neolithic villages and towns served the needs of their inhabitants and immediate neighbors, cities decisively influenced the political, economic, and cultural life of large regions. Cities established marketplaces that attracted buyers and sellers from distant parts. Brisk trade, conducted over increasingly longer distances, promoted economic integration on a much larger scale than was possible in neolithic times. To ensure adequate food supplies for their large populations, cities also extended their claims to authority over their hinterlands, thus becoming centers of political and military control as well as economic influence. In time, too, the building of temples and schools in neighboring regions enabled the cities to extend their cultural traditions and values to surrounding areas. The earliest known cities grew out of agricultural villages and towns in the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in modern-day Iraq. These communities crossed the urban threshold during the period about 4000 to 3500 B.C.E. and soon dominated their regions. During the following centuries cities appeared in several other parts of the world, including Egypt, northern India, northern China, central Mexico, and the central Andean region of South America. Cities became the focal points of public affairs—the sites from which leaders guided human fortunes, supervised neighboring regions, and organized the world’s earliest complex societies. I n many ways the world of prehistoric human beings seems remote and even alien. Yet the evolution of the human species and the development of human society during the paleolithic and neolithic eras have profoundly influenced the lives of all the world’s peoples during the past six millennia. Paleolithic peoples enjoyed levels of intelligence that far exceeded those of other animals, and they invented tools and languages that enabled them to flourish in all regions of the world. Indeed, they thrived so well that they threatened their sources of food. Their neolithic descendants began to cultivate food to sustain their communities, and the agricultural societies that they built transformed the world. Human population rose dramatically, and human groups congregated in villages, towns, and eventually cities. There they engaged in specialized labor and launched industries that produced pottery, metal goods, and textiles as well as tools and decorative items. Thus intelligence, language, reflective thought, agriculture, urban settlements, and craft industries all figure in the legacy that prehistoric human beings left for their descendants. 26 CHRONOLOGY 4 million–1 million years ago Era of Australopithecus 3.5 million years ago Era of Lucy 2.5 million–200,000 years ago Era of Homo erectus 200,000 B.C.E. Early evolution of Homo sapiens 200,000–35,000 B.C.E. Era of Neandertal peoples 13,500–10,500 B.C.E. Natufian society 10,000–8000 B.C.E. Early experimentation with agriculture 10,000–300 B.C.E. Jomon society 8000 B.C.E. Appearance of agricultural villages 4000–3500 B.C.E. Appearance of cities 3000 B.C.E.–1850 C.E. Chinook society 27 Terms on the margins: Australopithecus Homo Erectus Migrations of Homo Erectus Migrations of Homo Sapiens The Natural Environment Relative Social Equality Big-game hunting Paleolithic Settlements Neandertal Peoples Creativity of Homo Sapiens Venus Figurines Cave Paintings Neolithic Era Independent Inventions of Agriculture The Early Spread of Agriculutre Emergence of Villages and Towns Specialization of Labor Pottery Metalworking Textile Production Social Distinctions Religious Values Emergence of Cities