Courtesy Hudson`s Bay Company

advertisement

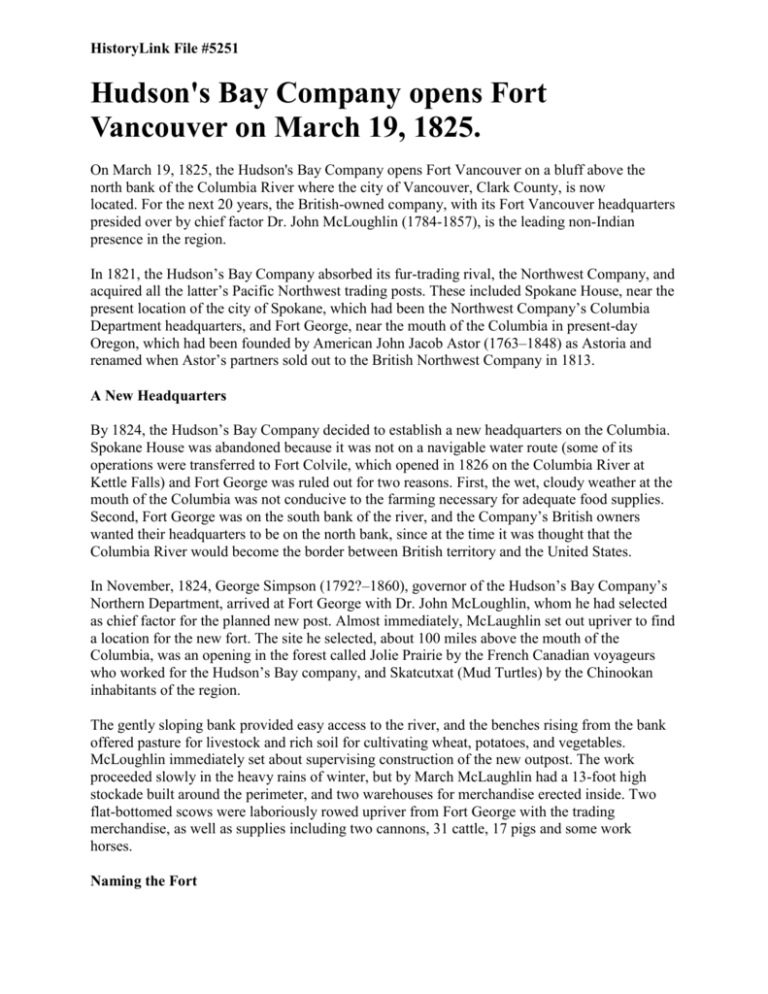

HistoryLink File #5251 Hudson's Bay Company opens Fort Vancouver on March 19, 1825. On March 19, 1825, the Hudson's Bay Company opens Fort Vancouver on a bluff above the north bank of the Columbia River where the city of Vancouver, Clark County, is now located. For the next 20 years, the British-owned company, with its Fort Vancouver headquarters presided over by chief factor Dr. John McLoughlin (1784-1857), is the leading non-Indian presence in the region. In 1821, the Hudson’s Bay Company absorbed its fur-trading rival, the Northwest Company, and acquired all the latter’s Pacific Northwest trading posts. These included Spokane House, near the present location of the city of Spokane, which had been the Northwest Company’s Columbia Department headquarters, and Fort George, near the mouth of the Columbia in present-day Oregon, which had been founded by American John Jacob Astor (1763–1848) as Astoria and renamed when Astor’s partners sold out to the British Northwest Company in 1813. A New Headquarters By 1824, the Hudson’s Bay Company decided to establish a new headquarters on the Columbia. Spokane House was abandoned because it was not on a navigable water route (some of its operations were transferred to Fort Colvile, which opened in 1826 on the Columbia River at Kettle Falls) and Fort George was ruled out for two reasons. First, the wet, cloudy weather at the mouth of the Columbia was not conducive to the farming necessary for adequate food supplies. Second, Fort George was on the south bank of the river, and the Company’s British owners wanted their headquarters to be on the north bank, since at the time it was thought that the Columbia River would become the border between British territory and the United States. In November, 1824, George Simpson (1792?–1860), governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Northern Department, arrived at Fort George with Dr. John McLoughlin, whom he had selected as chief factor for the planned new post. Almost immediately, McLaughlin set out upriver to find a location for the new fort. The site he selected, about 100 miles above the mouth of the Columbia, was an opening in the forest called Jolie Prairie by the French Canadian voyageurs who worked for the Hudson’s Bay company, and Skatcutxat (Mud Turtles) by the Chinookan inhabitants of the region. The gently sloping bank provided easy access to the river, and the benches rising from the bank offered pasture for livestock and rich soil for cultivating wheat, potatoes, and vegetables. McLoughlin immediately set about supervising construction of the new outpost. The work proceeded slowly in the heavy rains of winter, but by March McLaughlin had a 13-foot high stockade built around the perimeter, and two warehouses for merchandise erected inside. Two flat-bottomed scows were laboriously rowed upriver from Fort George with the trading merchandise, as well as supplies including two cannons, 31 cattle, 17 pigs and some work horses. Naming the Fort On the morning of March 19, 1825, Simpson, with McLoughlin at his side, presided over a formal christening of the new fort. A flagpole was erected, the Hudson’s Bay Company flag run up, and Simpson smashed a bottle of rum on the pole. He then declared: "In behalf of the Hon[orable] Hudson’s Bay Co[mpany] I hereby name this Establishment Fort Vancouver God save King George the 4th" (Fort Vancouver, 27). Simpson later explained his reason for naming the fort for British Royal Navy Captain George Vancouver (1757-1798): "The object of naming it after that distinguished navigator is to identify our Soil and Trade with his discovery of the River and Coast on behalf of Great Britain" (Fort Vancouver, 27). Simpson’s claims for Vancouver’s discoveries were considerably exaggerated. Not only had Chinookan-speaking peoples been living along the Columbia, which they called Wimahl (Big River), for thousands of years, but Vancouver’s 1792 expedition was not even the first nonIndian party to enter the River, having been preceded by American Captain Robert Gray (17551806) earlier that year. Still, the name was a reminder that Lieutenant William Broughton (17621821) of the Vancouver expedition had explored the Columbia to some miles above the new fort’s location (farther than Gray had), where he had named a point for Vancouver. Both the establishment of Fort Vancouver, and its name, served notice that the Hudson’s Bay Company, and Great Britain, were not giving up their claims to the Columbia River region. For some 20 years, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fort Vancouver, presided over by Dr. McLoughlin, remained the major non-Indian presence in the future Washington. Gradually, however, more and more American settlers poured into the region, many of them obtaining supplies and advice at Fort Vancouver. When the issue was finally resolved in 1846, the international boundary was established not on the Columbia River, but along the 49th parallel several hundred miles to the north, and the Hudson’s Bay Company ultimately relinquished its fort to the United States Army. Sources: Fort Vancouver (Washington, D.C.: Division of Publications, National Park Service, 1981), 2627, 43, 54-56; Charles G. Ellington, The Trial of U.S. Grant (Glendale, CA: A. H. Clark Co., 1987), 105-06; Rick Rubin, Naked Against the Rain (Portland, OR: Far Shore Press, 1999), 299302. By Kit Oldham, February 20, 2003 Dr. John McLoughlin (1784-1857), ca. 1856 Courtesy Hudson's Bay Company Flag of the Hudson's Bay Company. Latin motto "Pro pelle cutem" translates "a skin for a skin" Courtesy Clark County Historical Museum (Image No. cchm04365.tif) Mount Hood, Columbia River, and Fort Vancouver, 1833 Courtesy Clark County Historical Museum (Image No. cchm04288.tif) Fort Vancouver, 1841 Sketch by Joseph Drayton, Courtesy Fuller, A History of the Pacific Northwest Fort Vancouver, 1845 Courtesy UW Special Collections (Neg. No. UW 26972z) Fort Vancouver, 1854 Courtesy UW Special Collections (Neg. No. WAS03073) Hudson's Bay Company's Fort Vancouver, 1855