Individual Educational Plans in Swedish Schools – Forming Identity

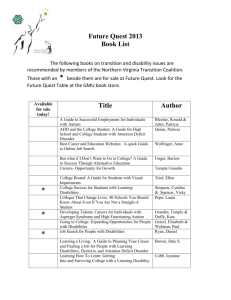

advertisement