A Contextual Reading of Matthew 6:9b-13

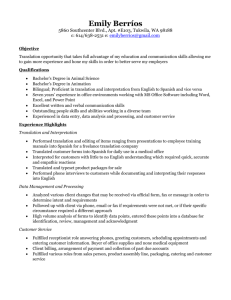

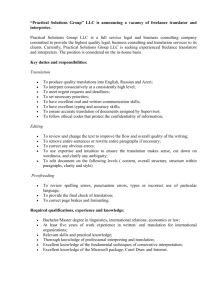

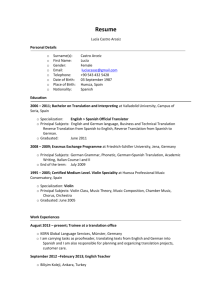

advertisement

Please do not cite this paper. It is still very much unfinished and unpolished. The ideas present are informed by other readings yet to be cited. This paper is simply to help other readers understand what I am trying to accomplish or experiment in the field of contextual hermeneutics. Matthew 6:9b-13: A Latino/a Optic on Translation Francisco Lozada, Jr. Brite Divinity School Introduction In the history of scholarship on the Lord’s Prayer in Matthew 6:9b-13, interpretations have primarily focused on the text’s history of composition, examining the prayer’s relationship to Q, the prayer’s comparative relationship to Jewish prayers, or its editorial development in relationship to Luke’s version of the prayer. Whereas a contextual dimension of the Lord’s Prayer background was explored, namely, the compositional history of the text, the context of the readers reading this text was not a focus of attention. In today’s paper, I aim to explore the context of the reader, myself, as well as another context of text’s background–the translation history of the text. The translation history will be explored briefly in this paper and extensively in depth at a later time. It is the context of this reader that will be given more attention this afternoon and it will be done by way of providing a Latino/a optic brought to the issue of translation of the Lord’s Prayer in Matthew. In contextual hermeneutics, as argued by many and as part of the assignment we were given, it is pertinent to take seriously the contexts of the reader and the text. But what does this mean? At times this principle has led to a delineation of the social location of the reader, although brief, yet vital to one’s reading of a text. At other times, this principle has led to an autobiographical reading of the reader, again although brief very important to the interpretative process. The principle has led to a third direction as well with a delineation of communities’ social and cultural condition in relationship to the text as illustrative of liberation hermeneutics across the globe. In all three directions, but especially the first two, the context of the reader and 1 Please do not cite this paper. It is still very much unfinished and unpolished. The ideas present are informed by other readings yet to be cited. This paper is simply to help other readers understand what I am trying to accomplish or experiment in the field of contextual hermeneutics. the context of the reader’s community need further exploration other than just naming one’s cultural and social location. Reading from a Latino/a optic, for me, is both about learning in relation to a particular condition reflected in the Latino/a community and other communities, but also an opportunity to use the text as a laboratory to explore the question of identity of the role of the reader in the interpretative process. My aim in this first part is to move toward this latter point further by taking seriously both the reader and the text. The aim is not meant to solidify the reader to the status of marginality or otherness by naming my context, but rather to change the perception of my context, that is, pushing my Latino identity away from a construction of otherness toward one of engagement with the wider world (Sugi). A second aim in this analysis is not intended to avoid the text and its development, but rather to bring balance to the reader and the text. These aims are behind today’s paper. As such, with regard to examination of the reader’s context, the focus of this first part will center on translation. Associated with translation is the element of language. Language is one identity factor that identifies my context, but it is also one that other readers—as many here in this room today can identify with as part of their identity and context. The issue of translation and language is also one that pertains to the issue of empire as it is with the Lord’s Prayer in Matthew as I will explore more in depth at a later time. In so doing, I shall provide a reading, informed both my identity as a child of colonized parents, but also by my identity as a US Latino living (second generation) in a context where translation is a matter of intercultural communication, power relations, and forms of domination (Young…..). This contextual background will be brought to bear on the Lord’s Prayer in Matthew and the issues of translation and interpretation that follow its production and reception. I shall argue that no translation is done from a neutral space, including the Lord’s Prayer in Matthew. Therefore, a Latino/a optic 2 Please do not cite this paper. It is still very much unfinished and unpolished. The ideas present are informed by other readings yet to be cited. This paper is simply to help other readers understand what I am trying to accomplish or experiment in the field of contextual hermeneutics. brought to bear on the issue of translation enables a different meaning of the prayer: one in which reads the translated prayer as a retranslation of colonial desires and contradictions, which are detrimental to marginal communities such as the Latino/a community in the US. Context of the Reader I have identified my context thus far along two lines: the first, as a child of colonized parents and second as a US Latino. In so doing, I aim to provide a glimpse of these two aspects through the topic of translation. As a child of colonized parents who migrated to the US from Puerto Rico and now identifying myself as a US Latino of second generation background, translation remains an issue of identity for me in the US as well as with many other communities in the US whose first language is not English, or, as in my case, whose first language is now English yet whose consciousness is still colored by Spanish (e.g., I still dream in Spanish at times) and whose mispronunciation of English and Spanish words point away from a notion of originality or native speech. In the case of English, various mispronunciation of English words point to my Latino identity as one whose context was not English, and, with Spanish, my pronunciation and dialect of words point to my not being a native of Latin America. This is not unique to my situation since language, vocabulary, and accents (away from what is considered standard or the model) will always point to where someone is located. As such, translation is quite complex and intertwined with all sorts of factors principally with language. In what follows, I aim to engage this topic of translation and language by way of autobiography but also by examining various issues related to the topic of translation. From Subject to Object: Translation and Language 3 Please do not cite this paper. It is still very much unfinished and unpolished. The ideas present are informed by other readings yet to be cited. This paper is simply to help other readers understand what I am trying to accomplish or experiment in the field of contextual hermeneutics. As one grew up very young speaking Spanish, and then losing much of its oral skills through the effects of assimilation on many fronts, translation of language and culture has always been at the forefront in terms of translating my identity for myself. In particular when one’s own communities in the US and in Latin American define identity strongly based on the sole characteristic of speaking Spanish, as in my case, the effects of displacing my identity as an Other—as with other individuals with similar experiences—even within my own community is the resultant effect (See Segovia…..).1 The language one speaks or does not speak in one’s own home, that is, the language of one’s parents, is a process of translating identity. When I do not speak Spanish or do choose within my own US Latino community or in Latin America or in the US in general, someone is translating something about me. I have strongly assimilated into US English-speaking society as some Latinos/as and Latin Americans perceive. I am recognize this reality when someone tells me that I speak like a “gringo,” indicating that I am someone different and different from native speakers. Other responses or interpretations included: I am now an “Americano” (US American) as with the case of my family in Puerto Rico, and, I am cast as one who does not care about the language as in the case of various communities in the US.2 At one time, I translated such comments as one who was too lazy to learn my parent’s language (or my parents were too lazy to teach me).3 This is no longer the case since I have detranslated such comments, that is, I have refused this particular translation. Though, I know that I am consistently transformed from a subject to an object. In other words, the U.S. Latino who goes to Latin America and finds himself/herself translated, due to their lack of Spanish finds 1 Also, see Matthew 26:73…..which provides a glimpse at the story level that accents were identity markers in antiquity. 2 There is “Americano” which points to being part of the bullish imperial north and there is “Amerícano” which points to the dream of living in the US…. (See Stavans…….). 3 See Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks…….. 4 Please do not cite this paper. It is still very much unfinished and unpolished. The ideas present are informed by other readings yet to be cited. This paper is simply to help other readers understand what I am trying to accomplish or experiment in the field of contextual hermeneutics. him/herself translated from a U.S. Latino to an Anglo, and a U.S. Latino without the command of the Spanish language goes into his/her own communities finds him/herself as not really Latino/a. These are the realities of migration, globalization, empire, or colonization and its resultant effects have a negative impact among many within a community. This experience is not unique to my situation; one can find this across many other communities in the US and across the globe. The reality is that we are always translating something or someone from subject to object—as I do myself when I translate others and when I translate the biblical text like the Lord’s Prayer. Hierarchy of Language As I mentioned, associated with the process of translation, exists language which consists in a hierarchy. In other words, similar to class, ethnicity/race, and nationality, language exists in a hierarchy. This is found evidenced within the English language. For example, those who speak closest to the “prestigious” English of England are considered closer to the original language and people. Likewise, in Spanish, those who speak the prestigious Spanish of Spain speak closest to the original language (Castilian Spanish) and people of Spain. This is quite illustrative of other languages as well I suspect. One can also take it even further to the context within the US, those who speak closest to the prestigious English of New England dialect are closer to the original language and people of the colonial period (e.g., William Buckley comes to mind). Those who speak the “non-prestigious” US English like the perceived less educated, rural society, and the regionalism of the South are further removed from the colonial period. Among US Latinos/as, whose roots are from Latin America, those who speak closer to the “prestigious” language of Latin American’s colonizer, Spain, are closer to Spain than to Latin 5 Please do not cite this paper. It is still very much unfinished and unpolished. The ideas present are informed by other readings yet to be cited. This paper is simply to help other readers understand what I am trying to accomplish or experiment in the field of contextual hermeneutics. America—even though those language and dialects of Spanish in Latin America are products of the historical colonization of the territory in Latin America and indigenous populations (see Poblete…..). Translation and language become part of the domination of a subject into an object. It is a process of achieving control, carried out through the process of translating language, culture, and people, and texts by the people being translated. The act of translation, as with the case of geographical landscape and texts, “is an act of desacralizing” as with the case of Australia, Ireland, New Zealand and Nigeria (see Young….and Stavans) where mapping became the necessary adjunct of imperialism,” and as with the case in US, where mapping became the necessary adjunct of imperialism by the English as well as by the French and Spanish. Translation also consists in a hierarchy with the formal correspondence perceived closer to the original text’s meaning than a dynamic approach within our own field of biblical studies. (See Gooder……) [More on this latter point needs development.] Translator The act of translation of a language always involves a translator. The translator is always involved—consciously or unconsciously—in “false” (as some employ) or alternative translations. The most famous in Latin American history is La Malinche (also known as Malintzin, Malinalli or Dona Marina) who served as a Nahua translator for Hernan Cortez and the Spanish Conquistadores, who relied on her for understanding almost everything about the native Costal Gulf peoples of Mexico whom they encountered (Stavans). Unfortunately, for some, she has been portrayed as a traitor, hence her name La Malinche (unpatriotic Mexican, see Stavans….). In her translations of places, she committed translations by representing another culture once removed from the indigenous culture but nonetheless a translation and interpretation 6 Please do not cite this paper. It is still very much unfinished and unpolished. The ideas present are informed by other readings yet to be cited. This paper is simply to help other readers understand what I am trying to accomplish or experiment in the field of contextual hermeneutics. of the original. Her role is similar to the role of Sacagawea who played role of translator for Lewis and Clark in the 18th century.4 Both of these women are no different than any of us who play the role of translator, including the translation of the text. We are once or twice removed from the original but nonetheless a translation and interpretation filtered through a particular lens. Similar occurrences occurred with the French and the Spaniards in North America. Whether it is an act of diplomacy, treachery, or an act of resistance, translations open up the space for the appropriation of a conquering culture through the role of translation (Sugirtharajah …….. ). Finally, with the Latino/a experience, which varies depending upon which generation (first, second, third) one is a part of in the US and ethnic background, and geographical location in the US to name a few factors, Latinos/as may speak a Spanish dialect considered by the “guard” of the language as a “non-prestigious” dialect that reflects their regional home country as opposed to those who speak a “prestigious” dialect of Spanish reflected by the “guard” of the language as from Latin America or Spain.5 The Spanish dialect in all its formations exists in a hierarchy for better or worse. At the same time, all Spanish-speaking people are engaged in the act of translation in the US and all are being translated by their pan-Latino/a constituencies as well as by the dominant English-speaking constituencies. For instance, for those who are recent immigrants from less developed countries in Latin America, their dialect of Spanish is typically perceived by many (not all) Spanish teachers (mainly by non-native but not exclusively) as not formal Spanish or not the Spanish spoken in Spain—which is the model Spanish taught in many high schools and university programs (Poblete……). The aim is to teach Spanish to Latinos/as 4 Actually, she translated Shoshone to Hidatsa who translated from Shoshone to French Charbonneau, who translated French to Labiche who translated from French to English to Lewis and Clark. See …….. 5 The guard I am referring to is the Real Academia Espanola de la Lengua……. 7 Please do not cite this paper. It is still very much unfinished and unpolished. The ideas present are informed by other readings yet to be cited. This paper is simply to help other readers understand what I am trying to accomplish or experiment in the field of contextual hermeneutics. as if they were Anglo-speakers and not Heritage speakers, that is, Latinos/as whose ancestors spoke Spanish at one time or whose aural skills are stronger than their oral skills or who leave certain letters out of their pronunciations (e.g., eta for esta which is very typical of Caribbean dialect)6 and writings (e.g., poyo for pollo, llo for yo) or use words what is sometimes called Spanglish--the mixing of Spanish and English words in syntax in the US (e.g., washerteria).7 These Latinos/as are often perceived as “weak” speakers rather than “strong.” They are judged by their pronunciations and writing skills as opposed to their knowledge. In other words, heritage speakers were perceived as having a lack of literacy and constantly corrected for their use of wrong standard Spanish orthography in Spanish classes. As such, many Latinos/as, those who traveled to the center from the periphery are constantly cultural translators. As cultural translators, they are translated by their use of Spanish. They also encounter other translated people and translate their own home experiences to each other to form new languages as with the case of Spanglish (Stavans….. What does all this have to do with translating the Lord’s Prayer? Translation and language as discussed already are intertwined in culture as many can attest to coming from different cultural contexts, and it involves power and a “betrayal” of sorts. As the Latin saying goes, tradutore, traiditore (translator, traitor) we are always moving away from the original as many Latinos/as and other marginal groups are doing by moving away from the standard use of a language (e.g., Spanish or English). But translation is not simply a one way process. It is a two way process in which I translate the text and the text translates me. It is a cultural interaction and, an act of re-empowerment (Sugi…). In my translation of the Lord’s Prayer, I aim to explore 6 7 See Poblete, p. 178. Ilan Stavens, Spanglish, p…… 8 Please do not cite this paper. It is still very much unfinished and unpolished. The ideas present are informed by other readings yet to be cited. This paper is simply to help other readers understand what I am trying to accomplish or experiment in the field of contextual hermeneutics. this cultural interaction and re-translate this text and myself in the process with the goal of exploring the text’s colonial desires. Context of the Text Given this background on translation and language from the view of a Latino/a optic, how would such a background play a role when applied to the Lord’s Prayer in Matthew (6:9b13). In this second part of the paper for today, I will explore briefly one traditional issue related to translation of the prayer. As a conclusion, I will propose some further question that I intend to explore in a more developed fashion. One of the major issues regarding Matthew’s prayer is how to translate the Greek words opheilēmata/tois opheiletais (“debts”/“debtors” or “trespass” / “those who trespasses”). As in any translation, a betrayal of the “original” exists.8 As such, the quest for the “original” meaning and context is an aim for translators. Such quest leads readers in the English-speaking world to decide which translation to use in Matthew’s prayer. Does one use “debts” /debtors” or “trespass” / “those who trespasses”? It is the former that has prevailed in many English translations.9 My point here is not to challenge the prevailing translation of Matthew 6:12, and thus argue for a different one over against “debts”/”debtors”. Rather, what I am proposing here 8 The notion of “original” is problematic. ASV (And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors); New American Standard (And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors); NIV (Forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors); RSV (And forgive us our debts, As we also have forgiven our debtors); NRSV (And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors); New American Bible (and forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors). In Spanish, Sagrada Biblia (como también nosotros perdonamos a los que nos ofenden); La Biblia de las Américas ( Y perdónanos nuestras deudas, como también nosotros hemos perdonado a nuestros deudores); La Biblia Latinoamerica (y perdona nuestras deudas, como tambien nosotros perdonamos a nuestros deudores; La Nueva Internacional (Perdónanos nuestras deudas, como también nosotros hemos perdonado a nuestros deudores). 9 9 Please do not cite this paper. It is still very much unfinished and unpolished. The ideas present are informed by other readings yet to be cited. This paper is simply to help other readers understand what I am trying to accomplish or experiment in the field of contextual hermeneutics. to explore the possibility of the changes one makes to this prayer when translation occurs. In other words, the material identity of the prayer changes when words are translated. It is this moment of translation that its identity changes. For instance, an “upper class” national Mexican who comes to the US is translated from a third-world Mexican to a third-world Latino/a; his or her identity changes. The Lord’s Prayer also changes its material identity during the process of translation. It is this change of material identity I am interested in exploring in this project and its ramifications for communities today when a Latino/a optic is brought to bear on it. In other words, how would the translated prayer change in the context of a Latino/a world for instance? The translation of opheilēmata/tois opheiletais as “debts” and “debtors” has its roots found in the KJV10 of the Bible of 1611, which drew its translations from the Latin Vulgate11 with the words debita and debitoribus. As readers have learned from Sugirtharajah’s work on the KJV’s reception history, these translations are part of the colonial enterprise of the British Culture and Empire, who imposed upon its colonies this translation that became the standard translation til the present (Sugi, ). Others important translators such as William Tyndale (1526) preferred “trespass” and “tresspassers” (“And forgeve vs oure treaspases eve as we forgeve oure trespacers”), yet Myles Coverdale (1535) in his translation of the prayer translates the Greek as “debts” and “debtors” (And forgeue vs oure dettes, as we also forgeue oure deters). John Wycliff in 1395 (and foryyue to vs oure dettis, as we foryyuen to oure dettouris) follows the same translation. The history of translation of Matthew’s Lord’s prayer varies in translations but the dominant tradition has remained along the lines of translating in English opheilēmata/tois 10 11 (And forgiue vs our debts, as we forgiue our debters). --KJV (et dimitte nobis debita nostra sicut et nos dimisimus debitoribus nostris )—Latin Vulgate 10 Please do not cite this paper. It is still very much unfinished and unpolished. The ideas present are informed by other readings yet to be cited. This paper is simply to help other readers understand what I am trying to accomplish or experiment in the field of contextual hermeneutics. opheiletais as “debts” and “debtors.” However, both are possible translations of the ancient Greek terms opheilēmata/tois opheiletais. With the translation of the Christian Bible into Latin in the 2nd-3rd century, English translators, by the 14th century, took the two key Latin words which looked similar to the English “debts” and “debtors,” from which they were translated and used in the prayer. In the Latin Catholic Mass, which bases the Lord’s Prayer on Matthew’s version, reads “Et dimitte nobis debita nostra, sicut et nos dimittimus debitoribus” which reads in English as “and forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us.”12 Given this brief history on the background of the English rendering of opheilēmata/tois opheiletais, how does a Latino/a optic impact the material identity of this part of the prayer? [What follows still needs much clarity and development.] In other words, How can a Latino/a perspective receive these words given the social-economic situation impacting them today? In what follows briefly, allow me to explore this line of questioning a bit more by way of several questions I have in mind. (1) First, how do I read these terms, “debts/debtors” or “trespass/those who trespass” given the Latino/a socio-economic realities today? (2) Second, given how these terms might be heard/read in English and Spanish how might these words change the material identity of the prayer? (3) In the Latino/a Christian (evangelical) context, where the prosperity gospel is in full bloom, how might the hearing/reading of the prayer change or be translated in relationship to the “American dream”? In conclusion, further analysis of several other key translation items needs analysis, such as “father,” “kingdom,” and “evil” in relation to how they impact the material reality of the 12 Latin-English Booklet Missal for Praying the Traditional Mass, Illinois: October 2009 (fourth edition), pp. 38-39. 11 Please do not cite this paper. It is still very much unfinished and unpolished. The ideas present are informed by other readings yet to be cited. This paper is simply to help other readers understand what I am trying to accomplish or experiment in the field of contextual hermeneutics. prayer. Not to mention that an analysis of the representation of the Matthean reality and its ramifications of this prayer for today’s readers, given the reader’s and the text’s historical and social reality regarding translation, will also follow. 12