saes1ext_abstract_ch30

advertisement

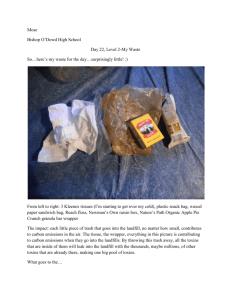

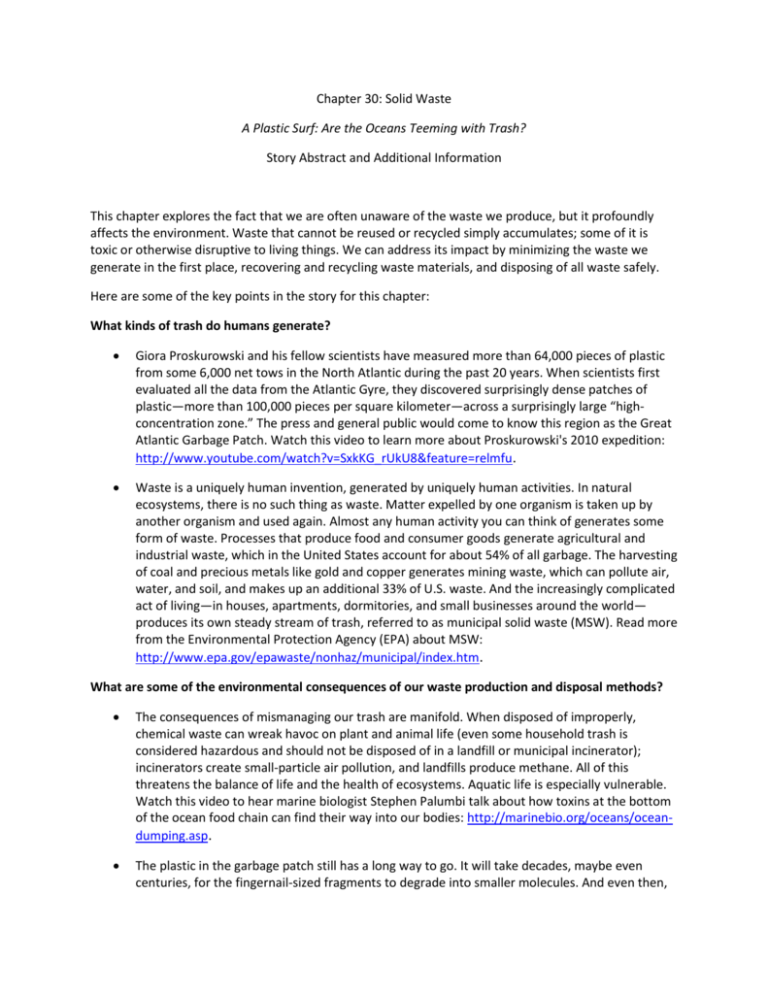

Chapter 30: Solid Waste A Plastic Surf: Are the Oceans Teeming with Trash? Story Abstract and Additional Information This chapter explores the fact that we are often unaware of the waste we produce, but it profoundly affects the environment. Waste that cannot be reused or recycled simply accumulates; some of it is toxic or otherwise disruptive to living things. We can address its impact by minimizing the waste we generate in the first place, recovering and recycling waste materials, and disposing of all waste safely. Here are some of the key points in the story for this chapter: What kinds of trash do humans generate? Giora Proskurowski and his fellow scientists have measured more than 64,000 pieces of plastic from some 6,000 net tows in the North Atlantic during the past 20 years. When scientists first evaluated all the data from the Atlantic Gyre, they discovered surprisingly dense patches of plastic—more than 100,000 pieces per square kilometer—across a surprisingly large “highconcentration zone.” The press and general public would come to know this region as the Great Atlantic Garbage Patch. Watch this video to learn more about Proskurowski's 2010 expedition: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SxkKG_rUkU8&feature=relmfu. Waste is a uniquely human invention, generated by uniquely human activities. In natural ecosystems, there is no such thing as waste. Matter expelled by one organism is taken up by another organism and used again. Almost any human activity you can think of generates some form of waste. Processes that produce food and consumer goods generate agricultural and industrial waste, which in the United States account for about 54% of all garbage. The harvesting of coal and precious metals like gold and copper generates mining waste, which can pollute air, water, and soil, and makes up an additional 33% of U.S. waste. And the increasingly complicated act of living—in houses, apartments, dormitories, and small businesses around the world— produces its own steady stream of trash, referred to as municipal solid waste (MSW). Read more from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) about MSW: http://www.epa.gov/epawaste/nonhaz/municipal/index.htm. What are some of the environmental consequences of our waste production and disposal methods? The consequences of mismanaging our trash are manifold. When disposed of improperly, chemical waste can wreak havoc on plant and animal life (even some household trash is considered hazardous and should not be disposed of in a landfill or municipal incinerator); incinerators create small-particle air pollution, and landfills produce methane. All of this threatens the balance of life and the health of ecosystems. Aquatic life is especially vulnerable. Watch this video to hear marine biologist Stephen Palumbi talk about how toxins at the bottom of the ocean food chain can find their way into our bodies: http://marinebio.org/oceans/oceandumping.asp. The plastic in the garbage patch still has a long way to go. It will take decades, maybe even centuries, for the fingernail-sized fragments to degrade into smaller molecules. And even then, they will not cease to pollute. In one study of the North Pacific Gyre, virtually all water samples, even those that were free of plastic debris, contained traces of polystyrene, a common plastic used in a wide range of consumer goods. Watch this video to hear Captain Charles Moore talk about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a cousin to the Great Atlantic Garbage Patch: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M7K-nq0xkWY. How can we reduce the amount of waste we produce? One promising solution to some of our waste woes involves converting garbage or its byproducts into usable energy. For example, the heat produced during incineration might be converted into steam energy or electricity. And the methane produced during anaerobic decomposition can also be harnessed as an energy source. Engineers and scientists are working out ways to capture the methane from landfills, and to use methane-producing microorganisms to process trash in vats or digesters. Read about a plant in New Jersey that converts trash into electricity: http://science.discovery.com/videos/how-do-they-do-it-6-turning-trash-intoenergy.html. In eco-industrial parks, industries are positioned so that they can use each other’s waste in the same industrial area; one company’s trash becomes another’s raw material. This type of strategic thinking is known as industrial ecology. In addition to “waste-to-feed” exchanges, participants in eco-industrial parks also decrease their ecological footprint by coordinating activities and sharing some spaces, like warehouses and shipping facilities. Read about how companies around the world are exploring this option at http://www.dw.de/dw/article/0,,6532982,00.html. Additional information about other topics from this chapter: The 100 Thing Challenge You can play a part in reducing the amount of trash we produce through four steps: refuse, reduce, reuse, and recycle. David Bruno has founded the 100 Thing Challenge to help people with the first step—refusing to use things we don't really need: http://guynameddave.com/100thing-challenge/.