How Genome Sequencing Works

advertisement

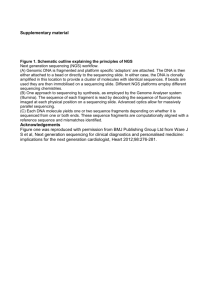

Name:__________________Hour:_____ As Genetic Sequencing Spreads, Excitement, Worries Grow by ROB STEIN Predict: What do you expect to find in this article? September 18, 2012 Slides containing DNA sit in a bay waiting to be analyzed by a genome sequencing machine. Ever since James Watson and Francis Crick cracked the genetic code, scientists have been fascinated by the possibilities of what we might learn from reading our genes. But the power of DNA has also long raised fears — such as those dramatized in the 1997 sci-fi film Gattaca, which depicted a world where "a minute drop of blood determines where you can work, who you should marry, what you're capable of achieving." One sentence summary of paragraph: That was science fiction. Just three years later, President Bill Clinton announced that the once-futuristic dream of reading someone's entire genetic code — their genome — had become a reality. It took hundreds of scientists nearly a decade to painstakingly piece together the first real look at the entire human genetic blueprint. It cost $3 billion just to make that rough draft. Twelve years later, the cost of deciphering a person's genetic instructions has dropped faster than the price of flat-screen TVs. And the sequencing can be done much quicker. One sentence summary of paragraph: The Cost of Sequencing A Genome Over the past decade, the cost of sequencing a human-sized genome has dropped dramatically. Since 2008, those cost reductions have outpaced Moore's Law, a famous forecast predicting the doubling of computing power every two years. Technology that keeps pace with Moore's Law is thought to be in good shape. Instead of years, it can take just weeks. Instead of an army of scientists, all it takes is a new high-speed sequencing machine and a few lab techs. Instead of billions, it can cost as little as $4,000. And many are predicting the $1,000 genome is coming soon. "It's incredible to me today to see how far we've advanced," said Robert Blakesley, who directs the National Institutes of Health's Intramural Sequencing Center. One company is showing off a sequencing machine that looks like a fat thumb drive, plugs into a laptop and supposedly spits out a sequence directly from a little blood within hours. One sentence summary of paragraph: . Some doctors are starting to sequence cancer patients to find the mutations behind their tumor. Oncologists can then sometimes find better drugs to treat them. Other specialists are using sequencing to diagnose mysterious genetic conditions. And some healthy people have even started getting sequenced just out of curiosity. "It is not theoretical or futuristic. It is today. And it is everyone," said George Church, a Harvard geneticist who started the Personal Genome Project. The project is trying to recruit thousands of people around the world to get sequenced and post their genomes on the Internet, along with as much detailed personal information as possible. "We are hoping to get a preview of personalized medicine — and share that preview worldwide," Church said. One sentence summary of paragraph: How Genome Sequencing Works It used to take hundreds of scientists years and billions of dollars to analyze one genome. Now high-speed sequencing machines can read a genome in weeks.All genome sequencing machines are designed to make sense out of DNA. DNA is made of two complementary, intertwined strands that fit together like two sides of a zipper. Each strand is written in a simple language composed of four letters that stand for different nucleic acids: A, T, C and G. The letters always pair the same way: A goes with T; C goes with G. To decode the letters in a piece of DNA, a sequencing machine figures out what letters stick to the DNA. With the price approaching the cost of getting an MRI, many predict that sequencing will soon become part of routine medical care. "You can imagine a day when our skin cells, for example, are screened periodically, and their genomes are looked at automatically as part of our life for signs of skin cancers, so we can better understand whether or not a particular part of our body is turning cancerous," said Nathan Pearson, a geneticist at Knome Inc., a Cambridge, Mass., company that interprets genomic information. One sentence summary of paragraph: But the idea of widespread sequencing is setting off alarm bells. How accurate are the results? How good are doctors at interpreting the results, which are often complicated and fuzzy? How well can they explain the subtleties to patients? The fear is that a lot of people could end up getting totally freaked out for no reason. And there are concerns about privacy. Scientists recently even sequenced a fetus in the womb, raising the possibility of everyone getting sequenced before or at birth — a prospect with a whole new set of questions and concerns. "I think there are lots of population-wide and individual dangers," said Mark Rothstein, a bioethicist at the University of Louisville. "We're basically not ready for a society in which very exquisite, detailed genomic information about every individual, potentially, is out there." Despite the concerns, it's clear that more and more people are going to be getting their genomes sequenced. The question is: Is society really ready for this flood of genetic information and everything that comes along with getting to know our genomes so well? One sentence summary of paragraph: