Derivational Morphology and the Competence and Intuition

advertisement

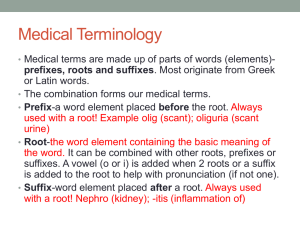

Derivational Morphology and the Competence and Intuition of Dutch L2 Learners of English: Suffixation BA Thesis English Language and Culture, Utrecht University Indira Wakelkamp 3379035 Prof. Dr. W. Zonneveld November 2011 Index 1. Introduction: Universal Grammar, Language Acquisition and the Goal of this Thesis p. 1 2. Morphology: Affixation p. 3 3. Derivational Morphology in Second Language Acquisition p. 7 4. Test p. 13 5. Results p. 19 6. Conclusion p. 33 Works Cited p. 38 Appendix p. 39 1 1. Introduction: Universal Grammar, Language Acquisition and the Goal of this Thesis Many theories of second language acquisition (L2A) consider the possibility of there being something like Universal Grammar (UG), and the independent possibility of its availability to second language (L2) learners. The UG theory is concerned with a possible blue-print of linguistic information that is innate to every child, no matter when or where it is born. This UG provides children with a framework that facilitates them in their acquisition of a certain language and, as long as the input is quantitatively sufficient and qualitatively accurate, ensures that each of them will acquire that certain language to a native level. The framework that is handed to the child consists of various Principles and Parameters that limit the number of linguistic options a child has. An example of one of those linguistic options is “subject drop is/ is not allowed”. Since all languages in the world either have subject drop, like Spanish for example, or do not have subject drop, like English, the child is aided in its acquisitional path if it knows from the start that it only has to make one choice (which it can do, based on positive evidence). “Subject drop” is an example of a parametric linguistic option, since it requires a certain setting based on input. In theory development, Parameters and their settings can be used to investigate and show how languages differ and where those differences can be found. Principles are different in that they are true for all languages in the world in exactly the same way and thus do not require a choice. This view of language and language acquisition is accepted as an interesting and promising framework to work in by many linguists all over the world, who investigate its main aspects. A major issue in this research, and one that underlies the current thesis, is whether UG is still available to learners of a second language. If this were the case (L1 learners and L2 learners both have equal access to UG), there would basically be no difference between first and second language acquisition and speakers would be able to 2 acquire a second language very easily and to a native level. Since research (and experience) has shown that this is not true, i.e. “full access” is very unlikely to be the case. It is, however, also not very likely that L2 learners have no access to UG at all. The fact, for instance, that L2 learners do not make mistakes that violate the Principles is proof that UG is at least partly available to them. A popular theory nowadays is that UG is fully available to learners when they are still in their critical period (up to age 12 approximately) and after that access to UG partly deteriorates, maintaining the Principles but learners lose the ability to set Parameters. Evidence for this is seen as coming from second language acquisition. The difficulties and frequently observed lack of full success in this process follow from the observation that usually second languages are acquired, at least beyond a beginners’ degree, after the end of the critical period; hypothesising that parameter setting, or, in this case, resetting, is then difficult if not impossible, will explain these characteristics. From a research perspective, the degree and manner in which parameter resetting is possible is subject to investigation. As pointed out, exactly the question whether UG is still available to learners of a second language essentially forms the basis of this thesis. With this question in mind it would be interesting to investigate how competent L2 learners actually are in the L2, hoping that the result of this kind of research would tell us something about the degree to which Parameters can be reset and whether the Principles are still used when learning a second language. Subsequently, these findings could then possibly also tell us something about the availability of UG after the L1 is acquired. It would of course be almost impossible to look at how competent L2 learners are in the L2 as a whole, therefore the investigation would have to be narrowed down to a particular phenomenon in a particular area of research. In this thesis the field of morphology in relation to second language acquisition (L2A) will be looked at, focusing on the phenomenon of derivation and more specifically, derivational affixation. 3 This particular topic has not only been chosen for reasons of the current author’s personal interest, but also because it seems that within the field of L2A not a lot has been written about Dutch L2 learners’ morphological competence. The main goal of this thesis is essentially two-fold. In an investigation of speakers with Dutch as their L1 and English as their L2, the goal is not only to see whether Dutch L2 learners of English “have competence” in the system with regards to English affixation and what their intuitions are, but also to see whether L2 learners of different levels of competence in English overall, show different degrees of competence in the specific task that was given to them. If the L2 learners turn out to “have competence”, or “growing competence”, in the system this might tell us something about the availability of UG to L2 learners. In order to test the morphological competence of these learners a so-called “fill in the blank” test was set up, the specific details of which will be discussed later. 2. Morphology: Affixation Morphology is the study of the internal structure of words. Building blocks of words are either bound or free morphemes. A free morpheme is a morpheme that is a complete word and can stand on its own. Examples of free morphemes are “house” (N), “fair” (Adj.) and “walk” (V). Bound morphemes are morphemes that need to be attached to something else (a word) and cannot stand alone, they are also known as “affixes”. Examples of bound morphemes are –ed in “walked”, -ly in “secretly” and im- in “impossible”. Both free and bound morphemes are stored in the mental lexicon along with rules of how they can be combined. Especially in the case of affixes there are certain rules that determine where they can be attached and what they can be attached to. Affixes can generally be subdivided into prefixes and suffixes. Prefixes are attached to the beginning of a word, whereas suffixes are 4 placed after the stem of a word (in some cases the truncation rule applies). Examples of both types are presented below. Prefixation: Suffixation: im- + possible (Adj.) = impossible (Adj.) big (Adj.) + -est = biggest (Adj.) dis- + connect (V) = disconnect (V) impair (V) + -ment = impairment (N) Suffixes can be divided into two categories: inflectional and derivational suffixes. The boundary between the two is not always clear, but roughly speaking inflectional affixes do not change word category (e.g. nouns stay nouns, verbs stay verbs etc.) whereas derivational affixes do (verbs can become adjectives, for instance): Inflection: Derivation: house (N) + -s = houses (N) eat (V) + -able = eatable (Adj.) cook (V) + -ed = cooked (V) blunt (Adj.) + ness = bluntness (N) Inflectional morphemes create different forms of a lexeme, i.e. it changes the grammatical property of a word within its syntactic category. Examples are English plurals and past tenses of verbs. Derivational morphemes create different lexemes, adding a derivational suffix to a word can change its syntactic category (see examples given above) and its meaning. Recalling the Introduction in which it was explained that all languages consist of a series of parametric choices that interact let us now look at the phenomena of stress, for which a number of parametric choices can be made, and how it interacts with morphology. Looking at the stress patterns of morphologically complex words in English it becomes apparent that in some cases the stress pattern of a word changes when an affix is attached to its root and in some cases it does not. In English, inflectional affixes never change stress, but derivational affixes often do. Since this thesis uses stress as a linguistic phenomenon of interest, inflectional affixes will therefore be left out of consideration. From this point 5 onwards it will solely be concerned with derivational affixes. Moreover, among the affixes it is specifically suffixes that will be dealt with, the reason being that in the word stress system of English (and Dutch) the assignment of stress to a certain syllable in a word has been shown in the literature to be heavily slanted towards the right-hand side of a word (Burzio, 92).From this point of view, derivational suffixes are generally divided into two categories: stress-placing or stress-sensitive suffixes (Type 1) and stress-neutral suffixes (Type 2), i.e. suffixes that affect the stress pattern and suffixes that do not. Each type contains its own affixes. Table 1: Examples of Type 1 and Type 2 suffixes (Marchand, 221) If, for example, in English the Type 1 suffix –ity is added to the word cáptive, the main stress shifts to the final stem position: captív-ity. If the Type 2 suffix –ness is added to the word sérious, the main stress stays in the same position: sérious-ness. A few suffixes can be placed in the category of mixed suffixes, meaning that in some cases the suffix is stress sensitive and in other cases it is stress neutral. A good example is the suffix –al: 6 Stress-neutral: Stress-sensitive: dismíss – dismíssalpárent – paréntal Morphology and prosody clearly interact with each other. It can be said that morphology feeds into phonology and that stress is applied sequentially through different levels of morphology. The figure below illustrates how morphology and phonology interact with each other. Figure 1: Interaction of Morphology and Phonology (Zonneveld, 48) Word stress is part of the Lexical Phonology, which takes place at word-level. From stressneutral affixation it becomes clear that the stress procedure must precede affixation. If we take the word “serious” for example, and add the Type 2 suffix –ness nothing is supposed to happen with the stress pattern after the suffix is attached. This means that if the underived word “serious” enters the model of the lexicon presented above it first gets assigned stress by lexical phonology, so it becomes ‘se-ri-ous, then it undergoes Type 2 affixation, and the suffix –ness is added. The stress pattern remains the same (‘se-ri-ous-ness) and the word can now leave the lexicon and move on to syntax through lexical insertion. Stress-sensitive affixation would then logically take place before stress is assigned. If the underived word “parent”, for example, enters the lexicon it undergoes Type 1 affixation when a suffix like –al 7 is attached to it. Stress is then assigned to the derived form parent-al, so it becomes par’en-tal, after which it can leave the lexicon straight away in the same way as described earlier (or a Type 2 affix may be added), (Zonneveld, 47). 3. Derivational Morphology in Second Language Acquisition In this chapter an overview of the current status of the field of the acquisition of derivational morphology will be provided. The current theories of the acquisition of L2 morphology will be discussed to establish a context in which this thesis can be placed and to further explain the theoretical basis for this thesis from the perspective of L2A. Friedline (2011) states that “The acquisition of second language morphology is a central concern to contemporary theories of second language (L2) acquisition. The domain of morphology is critical to these theories because learners have very special problems acquiring morphology” (Friedline, 1). Most studies in the field of the acquisition of L2 morphology, however, tend to be focused on inflectional morphology and it seems that very little work is specifically aimed at derivational morphology, even though derivation is a clear learning task for L2 learners that might very well cause difficulties. As mentioned before, certain affixes can, for example, only be attached to words of a specific class and some affixes change the syntactic category of a word whereas other do not. Not to mention the fact that placing affixes in the class of either stress-neutral of stress-sensitive affixes is clearly also a learning task, along with the ordering rules of affixation and the place where they can be attached. On top of that, the rules of derivation could apply to all members of a word class, but not every derived word that can be formed according to these rules necessarily occurs in the language. This means that there are constraints on word formation that L2 learners will have to learn (Jackendoff, 49). Jarmulowicz (2006) describes the learning tasks as follows: 8 […] learning suffixes must minimally entail (a) isolating the suffix, (b) learning the meaning of the suffix, (c) determining the syntactic constraints of the suffix (i.e. what lexical category the suffix marks and to which lexical category the suffix can attach). And (d) determining the morphophonological constraints and patterns associated with the suffix (Jarmulowicz, 295). Friedline (2011) states that “The term ‘morphological knowledge’ implies that a speaker knows something about the form, meaning and usage of a set of inflectional (e.g. case, tense and agreement) and/or derivational (e.g. –ness is a nominalising suffix in English) affixes in a given language” (Friedline, 13). Based on the discussion by Tyler and Nagy (1989) Lardiere (2006) has classified the various aspects of knowledge of derivational morphology into three types: 1. Relational knowledge. This is the knowledge (or perception) that two words are morphologically related to each other, that is, they share a common lexical base. 2. Syntactic knowledge. This is the knowledge that derivational suffixes mark words for syntactic category in English. Even if one does not know the lexical stem of a word, the derivational suffix can often provide highly reliable information about its syntactic category. 3. Selectional knowledge. This knowledge of the selectional restrictions on the concatenation of stems and affixes. Learners also need to know restrictions on which specific affix (es) to use in the derivation of a particular syntactic category given the morphophonological characteristics of the stem and/or the intended function. (Lardiere, 73) 9 In L1 acquisition, studies conducted among native English-speaking children suggest that these types of morphological knowledge develop at different rates. Research conducted by Tyler and Nagy (1989) among native English-speaking schoolchildren shows that by third or fourth grade children had acquired at least some relational knowledge, while their syntactic and selectional knowledge of derivational morphology started to increase gradually through the 8th grade (Tyler and Nagy, 3). Apart from processing differences between the different types of knowledge of derivational morphology, there might also be processing differences between knowledge of inflectional and derivational morphology. Looking at the speech of aphasic patients, for example, their ability to process inflection is often impaired while their ability to process derivation has often remained intact, suggesting that inflection and derivation are processed differently in the brain. At this point, it can be concluded that the rate of development of the different types of knowledge op derivational morphology differs and that some types of knowledge develop at an earlier stage in L1 learners than other types. Apart from this processing difference, there might also be a processing difference between inflectional and derivational knowledge. From this conclusion it could be derived that if these processing differences are found in native speakers as they acquire their L1, they are likely to also occur in learners of L2 morphology. Lardiere (2006) studied the English speech of Patty, a native speaker of Mandarin Chinese who had immigrated to the United States at the age of 22, and found that Patty would often produce incorrect derivational forms that were related to the syntactic and selectional knowledge of derivational morphology, while she never made any mistakes of a relational nature (Lardiere, 76). This finding is consistent with the acquisition rate of the three types of morphological knowledge that Tyler and Nagy (2008) found in L1 acquisition. Lardiere (2006) found that where errors occurred in Patty’s oral and written production 10 “they seem to implicate both the incomplete acquisition or morphological mapping (i.e. knowing which forms “go with” which features or category) and performance error (e.g. in lexical retrieval)” (Lardiere, 78). In order to explain how L2 lexical representations are acquired Jiang (2000) has proposed three stages of L2 lexical development: 1. Formal stage 2. Lemma mediation stage 3. L2 integration stage It is explained that in the first stage morphological, syntactic and semantic knowledge of an L2 lexical entry are not yet stored in the lexicon but that only orthographic and phonological knowledge of the L2 lexical entry are stored. L2 learners tend to associate an L2 lexical entry with the L1 translation of that entry, which gets activated. If this association between L1 and L2 lexical entries continues to be activated the L1 lemma will transfer into the L2 lemma space in the second stage. Syntactic knowledge of the L2 lexical entry will be added to the L2 lexicon as well as the L1 syntactic and semantic specifications associated with the L2 lexical entry. Because morphological knowledge is very language specific this knowledge tends not to transfer from L1 to L2 in this stage. In the third and final stage semantic, syntactic and morphological information is added to the L2 lexical entry (Jiang, 4/5). Based on different acquisitional as well as psycholinguistic studies Jiang (2000) suggests that L2 learners may fossilise at the second stage of the model explained above. This would mean that L2 learners might never get to the stage where morphological knowledge gets added to the L2 lexicon. This does, however, not mean that L2 learners do not have access to morphological knowledge (Jiang, 6). Jiang (2000) suggests that L2 will have access to explicit morphological knowledge, and that the degree to which L2 learners 11 will be able to apply this explicit knowledge depends on the processing resources that are available. Based on this point Friedline (2006) concludes that “This process is fundamentally different from the L1 lexical retrieval process in that morphological information is a conscious process that is applied outside of the lexicon. For natives, morphological knowledge is fully integrated into the lexical entry and accessed during lexical retrieval” (Friedline, 20). Jiang (2000) continues to explain that L2 lexical entries often consist of a kind of default or base forms, meaning that its inflected variants are not included. As a consequence of not including affixes in the lexical entry of a word L2 learners tend to not include morphological rules for the lexical entries either. The rules can be acquired by formal instruction, but will never be processed in their system in the same way as they do in the native system (Jiang, 23). Friedline (2011) has conducted a series of tests on L2 learners’ knowledge of derivational morphology using the following hypotheses based on different studies (direct references have, unfortunately, not been included). These hypotheses basically provide an overview of what researchers currently assume about the workings of the acquisition of L2 derivational morphology as well as a kind of summary of the current status of the field: 1. L2 learners acquire L2 derivational knowledge gradually and may plateau before reaching native-like levels of L2 competence (Jiang, 2000 ; 2002) 2. Learner characteristics such as L1 background affect how L2 learners acquire derivational knowledge. 3. The complexity of the structure (linguistic rules vs. metalinguistic concepts) influences how easy a structure is to acquire in terms of explicit/implicit knowledge. 4. Receptive derivational knowledge is more fully developed than productive knowledge among L2 learners. (Friedline, 26) 12 The most interesting findings/conclusions of Friedline (2011) are that language proficiency and L1 influence have a very limited effect on L2 derivational knowledge, although there might be L1 transfer, and that L2 learners of English appear to have gaps in their derivational knowledge that are found even in the most advanced stages of acquisition (Friedline, 120). The latter point might be explained by the differences in the rate of the development and processing of the different types of morphological knowledge that have been discussed above, as well as Jiang’s point that because of the difference between the workings of the L1 and L2 mental lexicon morphological knowledge is processed differently in the L2 system compared to the native system. These findings suggest derivational morphology will continue to cause difficulties for L2 learners of English at all levels. Another thing to bear in mind is the point that point Tyler and Nagy (1989) make, suggesting that there might be a possibility that the problems that L2 learners face with derivational morphology might also be connected to “general limitations on the students’ reading, vocabulary and test-taking abilities rather than a lack of knowledge about the morphological relationship between derivates and their stems” (Tyler and Nagy, 656). Looking at the difference between stress-sensitive and stress-neutral suffixes Jarmulowicsz (2006) suggests that learners less often use stress-sensitive suffixes to fill lexical gaps than stress-neutral suffixes, and that stress-sensitive suffixes are therefore less productive (Jarmulowicz, 295). Jamulowicz (2006) continues to explain that “neutral suffixes are more semantically and phonologically transparent and are used more productively to form new words, whereas the relationship of non-neutral derivatives to their stems is often phonologically and semantically obscure, or both” (Jarmulowicz, 295). We have now seen that there are differences in the rate of the development and processing of the different types of morphological knowledge, and that there are differences 13 between the workings of the L1 and L2 mental lexicon that suggest that morphological knowledge is supposedly processed differently in the L2 system compared to the native system. We have also seen that each of these factors may have consequences for the L2 acquisition of derivational morphology, namely that derivational morphology could continue to cause difficulties for L2 learners of English at all levels. This theoretical background will be relevant for the analysis of the test results later on, and will help with the formation of the hypotheses for this test, which will be discussed in the next chapter. The learning tasks as described by Jarmulowicz (2006) and the different types of morphological knowledge as described by Jiang (2006) will be taken into account and will be useful for the design of the test. The test will be set up in such a way that at least some, if not all, of the learning tasks are incorporated and that each type of morphological knowledge is tested. Jamulowicz’s (2006) point about the productivity of stress-sensitive and stress-neutral suffixes will also be taken into account and will aid the formation of a correct hypothesis regarding this issue. 4. Test Recall the introduction in which it was explained that the goal of this thesis is not only to see whether Dutch L2 learners of English “have competence” in the system with regards to English affixation (i.e. what comprises their morphological knowledge) and what their intuitions are, but also to see whether L2 learners of different levels of competence in English overall, show different degrees of competence. A “fill in the blank” test was set up to test the morphological competence and intuition of Dutch L2 learners of English in greater detail. The test consists of forty sentences that each contain a gap/blank where the participants had to fill in a word. At the end of each sentence the participants were given a word between brackets; the words that were meant to be filled in on the blanks could be formed by adding a suffix to the word between brackets. 14 The test can be found in the appendix (see Appendix A). The test was conducted among twenty secondary school pupils in their final year and twenty second year students of English Language and Culture. On average the secondary school pupils had received six to eight years of formal instruction in English, whereas the second year students had received seven to nine years of formal instruction. The results of each of these groups of participants will be compared to one another in the next chapter. Furthermore, the test was also conducted among ten native speakers of English. These participants will serve as a control group. The test has been set up to include only derivational suffixes under the assumption that Dutch learners of English as a second language are usually more familiar with inflectional morphemes because in general, the curriculum of second language teaching programmes in The Netherlands tend to be based on prescriptive grammar with a main focus on tense and word ordering rules. Therefore, it is expected that correctly using derivational suffixes will be slightly more difficult and it puts their morphological language intuition to the test. Seeing as derivational suffixes can change the syntactic category and meaning of a word this also tests the participants’ understanding of the given sentence and whether they understand what kind of word category needs to be inserted. However, the focus of this test is on suffixation and the morphological competence of the second language learning participants, therefore the test sentences have been kept as syntactically simple as possible so that the sentences were less likely to cause confusion or misunderstanding. The sentences were also designed to be semantically comprehensible and were formulated in such a way that they would provide a very clear context for the targets to appear in, making the meaning of the targets as clear as possible. 15 As target words, words were used that are common and relatively simple and lowregister so that the secondary school students at this level in particular would not struggle with the difficulty of the words. This did, however, cause some issues given the division of the target words which will be discussed in the next paragraph. Because the words were to be simple but were also subject to two types of categorical divisions (e.g. Type 1 vs. Type 2 suffix and Dutch vs. no-Dutch equivalent), it was hard to come up with words that fit all of these criteria. Therefore, some target words have a very clearly identifiable stem, whereas other do not. The word “attendance” for example is clearly made up out of attend + -ance whereas “importance”, which is related to “important”, is a less clear case of affixation. The current author is aware of the fact that this has introduced a difficulty in the test, but, on the other hand, it also makes the test potentially more interesting in the sense that the two kinds of affixation may be expected to lead to different results. In order to make sure the participants fully understood the task, two examples were shown before the start of the actual test. The participants were given ten to fifteen minutes to complete the test and each group of participants has been tested separately. In the test both Type 1 and Type 2 suffixes have been used. The system of Dutch and English with respect to word stress assignment and the interaction with morphology is the same, i.e. in Dutch there is also a distinction between stress-neutral and stress-sensitive and therefore Dutch also has Type 1 and Type 2 suffixes. Examples of each type in Dutch are riváal vs. ri-va-li-téit (Type 1) and pro-bléem vs. pro-bléem-loos (Type 2). This means that maybe there is no learning task for the L2 learners here. However, individual suffixes will obviously have to be placed in one category or the other and that clearly is a learning task. Independently of this issue, it can be argued that either stress-sensitive or stress-neutral affixation is the easier to learn word-class. Stress-sensitive might be easier to learn because 16 that kind of stress system is independently motivated for morphologically non-complex words. From this point of view stress-neutral affixation would seem more difficult. However, stress-neutral affixation is simply a matter of adding and then the task is done. Research conducted by Tyler and Nagy (1989) suggested that stress-sensitive suffixes presented L1 learners of English with more difficulties than stress-neutral suffixes, confirming that stressneutral suffixation is the easier task. Therefore, it seems likely that this would also be the easier task for L2 learners and stress-sensitive affixation the slightly more difficult one. This leads to the expectation that especially the secondary school pupils will have more trouble with the Type 1 words than the Type 2 words. For each suffix type five different suffixes were selected, and for each suffix four different target words. The complete list of words and suffixes used in this test, ordered by suffix types, looks as follows: Type 1: -ic (athletic, anatomic, catastrophic, majestic) -al (monumental, continental, parental, accidental) -ity (activity, sentimentality, personality, immortality) -ify (solidify, personify, humidify, solemnify) -ion (concentration, demonstration, desperation, hesitation) Type 2: -able (comfortable, acceptable, enjoyable, predictable) -ant (assistant, resistant, complainant, contestant) -ment (entertainment, management, punishment, improvement) -ance (importance, tolerance, attendance, appearance) -ive (effective, defensive, addictive, supportive) 17 The first two words for each suffix have a Dutch equivalent that is very similar (see Table below); the secondary school pupils in particular can be expected to have less trouble with these words than the ones that have no Dutch equivalent. These words have been put into the test in order to hopefully “force” the participants to rely on their morphological knowledge of English for the other half of the words that are not similar to Dutch rather than projecting their knowledge of Dutch onto the second language. Table 2: Dutch Equivalents (Note: the suffix en in Dutch “solidificeren” and “personificeren” is an inflectional suffix to mark the infinitive.) 18 This division of Dutch equivalent vs. no Dutch equivalent, however, is the source of some apparent difficulties. Some Dutch equivalents are very similar (e.g. Dutch “comfortabel” vs. English “comfortable”) whereas others might be less clearly similar (e.g. Dutch “tolerantie” vs. English “tolerance”) In this particular case subjects might respond with “tolerancy”, which, although incorrect in English, is even more similar to Dutch than “tolerance”. The Dutch equivalents of “solidify” and “personify” might be less clear because for these words the Dutch inflectional suffix –en has been attached after the suffix. The words “management” and “entertainment” are English loanwords that have been incorporated into the Dutch language; therefore these equivalents are exactly the same whereas all the other equivalents are only similar. Also, “supportive”, “personality” and “immortality” would respectively be translated into Dutch as “ondersteunend”, “persoonlijkheid” and “sterfelijkheid” and have therefore been placed in the category of no Dutch equivalents, however, they can also be translated as “supportief”, “personaliteit” and “immortaliteit”. Although the latter translations are much less common, they are accepted in Dutch, implying that these words could also be seen as Dutch equivalents of the English words, which causes an additional problem with the test. Since the second year students of English have received more years of formal instruction in English compared to the secondary school pupils, their morphological competence can be plausibly expected to be more advanced, resulting in better results in this task. In general, it has to be pointed out that due to the limited timeframe available the current test has a very rough experimental design and, as already pointed out, it contains a number of flaws that the current author is very much aware of. 19 5. Results Before addressing the test results, a few general points have to be made regarding the results and how this chapter has been structured. First of all, the results will be discussed per group of subjects and in comparison to one another. The difference in results per suffix type will also be looked at, as well as the results for the Dutch equivalent vs. no Dutch equivalent types. Secondly, the word types in the responses and the types of mistakes that were made will also be described. The tables that contain all the responses can be found in the appendix (see Appendix B and C). The results of the native speaker control group will be discussed in the final section of this chapter. It should be pointed out from the beginning that there were a number of problems with the data, some of which will be discussed later. However, it will probably be useful to point out now that in the mistakes that were made some of the data had to be cleaned up, as they were deemed unusable for a number of reasons. In some cases the participants failed to do the task and simply filled in a question mark or left the gap blank, and in some cases the participants had only filled in the stem that was given without attaching a suffix, despite the fact that they were explicitly told before the start of the test that only the stem could never be the correct answer. If these data were to be left out of consideration this would reduce the number of mistakes that were made and make it look like the participants did seemingly better than they actually did. Therefore, I have decided to count them as mistakes, but to also list the total number of them separately in the tables that will be presented later on in this chapter. First, let us have a look at the overall results of the secondary school pupils and the students of English in general. 20 Graph 1: Overall results As is clear from the graph the students of English have made considerably fewer overall mistakes than the secondary school pupils and have done better judging by the amount of incorrect answers. This is in line with the prediction that was made in the first chapter of this thesis. The number of incorrect responses have been further divided into two more graphs; one that shows the number of incorrect answers for Type 1 vs. Type 2 suffixes, and one that shows the number of incorrect answers for affixes that had a Dutch equivalent vs. those that did not. These graphs are presented below. 21 Graph 2: Results Stress-sensitive vs. Stress-neutral Graph 3: Results Dutch equivalent vs. no Dutch equivalent 22 Again, these graphs show that the students of English have done better compared to the secondary school pupils. However, it is interesting to note that both groups of subjects have made more mistakes with the Type 1 or stress-sensitive suffixes as well as with the suffixes that had no Dutch equivalent. So, despite the fact that the students of English did better overall, the majority of the problems still occurred in the same categories that the secondary school pupils also had most problems with. Although the overall competence of students of English generally really must be more developed than that of secondary school pupils, the fact that they both struggle most with the same issues could indicate that this is and possibly even remains a problem for relatively advanced Dutch L2 learners of English. Looking at the data in greater detail, the tables below show the number of correct and incorrect responses for each suffix and each word. Separate tables have been made for the responses for stress-neutral and stress-sensitive suffixes. First, the results of the secondary school pupils will be discussed, starting with an analysis of the results for the stress-neutral suffixes. Table 3: Results secondary school pupils stress-neutral 23 This table shows that most mistakes were made with the –able, -ance and -ant suffixes and not a single mistake was made with the –ment suffix. The latter can, at least for the Dutch equivalents, be explained by the fact that these words are also used in Dutch, as pointed out in the previous chapter. There is also an issue with the –ant suffix, because for “resistant” and “assistant” the subjects have used Dutch spelling (ending in –ent) for these words in quite a number of cases. It is not clear whether this should be considered an actual mistake or not, therefore it should be mentioned that this fact should be kept in mind when looking at the data for these particular words. Another interesting finding is that only one mistake was made for “appearance” and eighteen mistakes were made with “attendance”, while, given the fact that both these words are of the same category, it would be expected that the subjects would do equally well for both. It would require an excessive amount of space (and time) to analyse every single mistake that was made, therefore those that stand out or that seem most interesting will be discussed. Looking at the nature of the mistakes (excluding the unusable data and the spelling mistakes with –ant), two general observations can be made: (1) The subject attached the incorrect suffix. (2)The subject attached an inflectional suffix (mainly to turnitems into verbs). Examples of these two cases that were found in the data are listed below. Only incorrect responses that occurred in the data three or more times have been listed for reasons of significance. 24 (1): (2): Table 4 & 5: Examples of incorrect responses stress-neutral (secondary school pupils) First, let us have a look at the cases of (1). For “addictive” both “addictable” and “addicting” occur in the data. Although they are both incorrect in English they would be of the same word class, namely adjectives, if they had been correct, so the subjects clearly did understand what type of word had to be used. They might have added the suffix –able because this suffix had already occurred in the test a few times before and perhaps also because the stem “addict” ends in a similar way to “predict”, which does take the suffix – able. For “enjoyable” both “enjoying” and “enjoyful” occur. In the case of “enjoying” this could be yet another flaw in the test because “enjoying” can be used in the context of this sentence in English (at least in spoken language), therefore the sentence should have been formulated in such a way that this answer is ruled out. For “complainant” both “complainment” and “complainer” occur. In the first case the subjects apparently failed to pick up on the fact that the sentence clearly does not allow for an adjective to be inserted on the blank, so not only have they added the wrong suffix but they have also used a word of the wrong word class. The case of “complainer” could be explained by the fact that in English the suffix –er is frequently used to turn verbs into 25 nouns, as is the case for “worker” and “viewer” for example, so the subjects might have taken this to be another case of that suffix.It is a correct term that could be used in English, for example in a context like “You are such a complainer.”, but in the context of the sentence the term “complainant” would be used. Perhaps an easier example/word should have been chosen for the test. In the case of “tolerancy” what was already predicted in the previous chapter turned out to be true, i.e. the subjects have probably used this incorrect form because phonologically it is very similar to Dutch “tolerantie”. In the cases of (2) the subjects have added either the inflectional suffix –s which marks third person singular in present tense or the inflectional suffix –ed which marks past tense. In the case of “accepted” this form would fit into the sentence that was given, so the difference between derivational and inflectional suffixes might have been unclear to the subjects, as well as the fact that inflectional suffixes were not to be used in the test. In the other cases where the subjects had added –ed, however, the sentence was formulated in such a way that it was very clear that only an adjective could be inserted on the blank. Clearly some subjects failed to notice that. For the cases where the subjects had responded with “complains” they had apparently failed to see that the sentence was formulated in such a way that only a noun could be inserted on the blank. From these examples it can generally be concluded that in most cases the subjects failed to grasp the idea of the type of word class that could be filled in on the blank. Turning to the secondary school pupils’ results for stress-sensitive suffixes the table below shows the following results: 26 Table 6: Results secondary school pupils stress-sensitive The table clearly shows that the suffixes –al , –ity and –ify had caused the most difficulties for the subjects, closely followed by the remaining suffixes in the test. As mentioned before the most mistakes were made with the class of stress-sensitive suffixes. By far the most “unusable” data was found for the –ify suffixes. In most cases subjects had simply responded with the stem that was already given, which could mean that they really had no idea whatsoever as to which, or what kind of, suffix could be attached to the words that take –ify. This could be because either they were not really familiar with the words that were given or with the suffix –ify. In the cases of “anatomic” , “majestic” and “hesitation” the subjects also often responded with only the stem. Looking at the nature of the mistakes that were made with this class of suffixes it was found that the aforementioned case of (1) also applies here, but interestingly there was only one case of (2). This case occurred for “parental” where a few subjects responded with “parents”, having added the inflectional suffix –s to mark plural. There were no cases in 27 which inflectional suffixes were added to form verbs. The cases of (1) are presented in the table below. (1): Table 7: Examples of incorrect responses stress-sensitive (secondary school pupils) For “catastrophic” the incorrect forms “catastrophical” and “catastrophal” occurred in the data. What is interesting about the first case is that the subjects have added the correct suffix –ic, which means that they appear to have the right morphological intuition, however for reasons unknown they somehow decided to also add the suffix –al. The same has happened with “accidentally”, where –al as well as –ly were attached. Even though this is a grammatical form in English it is incorrect in the context of the sentence. The case of “catastrophal” might be another case of L1 interference, seeing as it is similar to Dutch “catastrofaal”. In the last three cases presented in the table above the subjects had attached the suffix –ly, a suffix that is mostly used to form adjectives from nouns or adverbs from adjectives. The sentence, however, required a noun to be placed where the gap is, so again the subjects did not only add the wrong suffix but they also formed a word of the wrong 28 word category, seeing as the responses are either adjectives or forms that would logically be classified as adjectives if had they occurred in the language. Another interesting point is that by adding the suffix –ly in the way that the subjects have done for these cases, the stress does not change. In most other cases in which the wrong suffix was attached the subject never attached a stress-neutral suffix when a stresssensitive suffix was required or vice versa. Another, perhaps less relevant but interesting case worthy of attention is that a number of subjects reduced “sentimental”, which was given, to “sentiment”, so rather than adding a suffix they took one off. These cases were, however, considered to be “unusable” mistakes for further analysis within this thesis. It can be concluded that for stress-sensitive suffixes only mistakes of type (1) were made (with only one exception), and again the subjects often responded with words of the wrong word class. Finally, the results of the students of English will be discussed, focusing on the stressneutral suffixes first. The results are listed in the table below. 29 Table 8: Results students of English stress-neutral What stands out when looking at the results presented in the table above is that the students of English made very little mistakes with the suffixes of this type. Most mistakes were made with the suffix –ant, which is mainly to do with the word “complainant”. The nature of the mistakes that were made with this word will be discussed later on, as well as another remarkable point that will come up when the results of the native speakers as a control group will be discussed. Also, there was very little “unusable” data in the responses. A striking fact is that the students of English never made any mistakes of type (2). This might suggest that they are aware of the difference between inflection and derivation. In addition, they also seemed to be very much aware of the word classes and the types of words that could be filled in on the blank, seeing that they never made any mistakes with this either. The mistakes that were made with “assistant” were spelling mistakes, just like the secondary school pupils had made (adding the Dutch suffix –ent, rather than the English –ant). 30 For “enjoyable” the subjects responded with “enjoying” in a few cases, the likely reason for this probably has to do with a flaw in the test for this case that was mentioned before. For “importance” a few subjects responded with “importancy”, thus adding the wrong suffix. As mentioned before, “complainant” is an interesting case. A few subjects responded with “complaintive”, which turned out to be an accepted alternative term for “complainant” in English. Others responded with “complainer”, like a number of secondary school pupils had also done. As mentioned before, “complainer” is a correct term in English, but within the context of the sentence the term “complainant” would be used. The test should probably have been more clear in this case. There were also a number of cases of “complaint” in the data, which is an interesting fact because even though this is a noun and therefore of the correct word class for this sentence, it creates a semantically ill-formed sentence because a complaint is inanimate and cannot “accuse”. It seems interesting that some of the students of English did not notice this. Now let us turn to the results for the stress-sensitive suffixes, which are presented in the table below. 31 Table 9: Results students of English stress-sensitive As becomes clear from the table below the amount of “unusable” data is minimal and most mistakes were made with the –ic and –ify suffixes. Examples of the nature of some of the mistakes are presented in the table below: (1) Table 10: Examples of incorrect responses stress-sensitive (students of English) For all the cases where the –ic suffix had to be attached, the students of English attached both –ic as well as the suffix –al, similar to what the secondary school pupils had done. There were also a number of cases of “catastrophal” (this was also found in the data for the 32 secondary school pupils). As mentioned before, this is probably a case of L1 interference. In the case of “solemnify” the subjects attached either the suffix –ise/-ize or –ate. There were five incorrect responses for “solidify”, the nature of which varied so much that they were not included in the table above because for each case there was only one response (in one case two), but the suffixes –ate and –ise/-ize were among them, similar to the suffixes that were attached to “solemn”. Finally, the results of the native speakers that served as a control group will be discussed. As the graph below shows, and as expected, the native speakers made very few mistakes. Similar tables to those that were presented for the secondary school pupils and the students of English were created for the results of the native speakers, but because they made very few mistakes the content of these tables are not as relevant and have therefore not been included here; they can instead be found in the appendix (see Appendix D) along with their responses (see Appendix E). Graph 4: Results native speakers 33 Around half of the number of the native speakers responded with “sentiment” for “sentimentality” and “anatomical” for “anatomic”. However, they were unanimous on all other cases where the suffix –ic had to be attached and responded correctly. The fact that half of the number of native speakers responded with “anatomical” might suggest that this is, in fact, allowed in English, therefore perhaps this should not be considered as a mistake for the other two groups of subjects. The students of English’ morphological intuition for this case therefore might have been correct, even though they had incorrectly over generalised it and used it for all cases of –ic. The fact that half of the number of native speakers responded with “sentiment” for “sentimentality” would then also suggest that this might be correct in English. 6. Conclusion The goal of this thesis was twofold. First, to see whether Dutch L2 learners of English “have competence” in the system with regards to English affixation and what their intuitions are, and second, to see whether L2 learners of different levels of competence in English overall, show different degrees of competence in the specific task that was given to them. If the L2 learners turn out to “have competence”, or “growing competence”, in the system this might tell us something about the availability of UG to L2 learners. This goal was put in the following context. English has two types of affixation: stress-sensitive and stress-neutral. Both were represented in a test that was conducted in order to meet the above twofold aim. Regarding the two types, it was hypothesised that the learners would have more difficulties with stress-sensitive suffixes than stress-neutral suffixes as well as with the suffixes that had no Dutch equivalent rather than the ones that did. 34 The assumptions underlying these hypotheses are respectively based on Jarmulowicz (2006) who suggests that learners less often use stress-sensitive suffixes to fill lexical gaps than stress-neutral suffixes, and that stress-sensitive suffixes are therefore less productive and, as a result, more difficult, and Jiang (2006) who suggests that L2 learners tend to associate an L2 lexical entry with the L1 translation of that entry, which gets activated. Therefore, L2 lexical entries that are similar to the L1 lexical entry will be easier to recognise and it will be easier to produce the correct L2 derivation if it is similar to the L1 form. Since the second year students of English had received more years of formal instruction in English compared to the secondary school pupils, it was hypothesised that their morphological competence would be more advanced, resulting in better results in the task. The results showed the following. Generally speaking, the students of English made less overall mistakes than the secondary school pupils, thus confirming the hypothesis that predicted that the students of English would have better results. It also became clear that both groups of subjects made more mistakes with the Type 1 or stress-sensitive suffixes as well as with the suffixes that had no Dutch equivalent, again, confirming the hypotheses. Despite the fact that the students of English did better overall, the majority of the problems, interestingly, still occurred in the same categories that the secondary school pupils also had most problems with. The fact that both groups, despite their different levels of competence, struggled most with the same issues, seems to indicate that this is and possibly even remains a problem for relatively advanced Dutch L2 learners of English. In general, two types of mistakes were made: 1. the subject attached the incorrect suffix, 2. the subject attached an inflectional suffix (mainly to turn items into verbs). The 35 secondary school pupils made mistakes of both types for the stress-neutral suffixes, while, interestingly, they hardly made any mistakes of type 2 for stress-sensitive suffixes. For both types of mistakes a third type was found exclusively in the secondary school children’s responses, namely: 3. the subject’s response was of the wrong word class. The secondary school pupils had many difficulties noticing what type of words, i.e. words from which word class, the sentences required and often made mistakes of this kind. Students of English never made any mistakes of type 2 and, in addition, they also never made any mistakes with word classes. If the knowledge about derivational morphology is divided into categories consistent with Lardiere (2006) as discussed in the third chapter of this thesis, it can be concluded from the nature of the mistakes that were made that both groups of subjects apparently had relational knowledge of L2 derivational morphology and that the syntactic knowledge of L2 derivational morphology was more developed in students of English compared to the secondary school pupils. It seems that the selectional knowledge remains difficult, even for more advanced L2 learners. This might have something to do with the difference between the workings of the L1 and L2 mental lexicon as explained by Jiang (2000) and could argue for the point that morphological knowledge is processed differently in the L2 system compared to the native system, suggesting that derivational morphology will continue to cause difficulties for L2 learners of English at all levels (Jiang, 2000). The results of the test appear to be consistent with this view and clearly show that problems remain even for learners that generally show an advanced level of competence and have received a lot of L2 input and formal instruction. This might suggest that the access to UG is at least limited when an L2 is acquired, because if learners had full access to UG logically they can be expected to acquire the L2 in a way similar to the acquisition of the L1. 36 This would mean that eventually the learners would arrive at a point where almost no mistakes are made, and the results strongly suggest that this is not the case. The fact that the students of English showed a more advanced level of competence compared to the secondary school pupils suggests that L2 derivational knowledge is likely to be acquired gradually and that the secondary school pupils are still in the earlier stages of L2 lexical development. The fact that problems remain even for learners that generally show an advanced level of competence could argue for Jiang (20000) point that learners may plateau before reaching native-like levels of L2 competence. However, as mentioned before, due to the limited timeframe available the current test has a very rough experimental design and, as already pointed out in the fourth and fifth chapter of this thesis, it no doubt contains a number of flaws. The results did show some level of conformity to the expectations as well as a level of consistency, which shows that the test has indeed tested something, yet it is important to keep these flaws in mind and it has to be made clear that the results as well as the conclusions can only be viewed within a context that takes the flaws of the test into consideration. For further research it would, of course, be necessary to omit these flaws in order to be able to draw more solid conclusions. It would perhaps also be interesting to design a similar test with nonsense words, because in that case subjects can only rely on their knowledge of the rules for derivation in English. It is possible that subjects have learned certain words in their derived form by formal instruction, and that these words have been stored in the lexicon in that form rather than just the stem along with the rules for derivation. This would mean that there is a chance that in some cases subjects do not intuitively apply the rules for derivation but that the derived form as a whole is immediately accessed when subjects notice a context for this form. When nonsense words are used this 37 chance is omitted as a factor and subjects’ knowledge of the rules for derivation is more thoroughly tested because subjects can only rely on that knowledge. This way even more insight into the morphological competence and intuitions of L2 learners could be gained. Another interesting point for further research is to look at the interaction of phonology and morphology in L2 acquisition in greater detail, and to test learners’ awareness of the difference between Type 1 and Type 2 suffixes and see whether they notice the stress change in the case of Type 1 affixation, and whether or not they correctly place stress in these cases. It can be concluded that despite the flaws of the test some interesting insights about the L2 knowledge of derivational morphology of Dutch L2 learners of English has been gained, however, there is still a lot more to discover by further research. Works Cited Burzio, L. (1994). Principles of English Stress. Cambridge: University Press Friedline, B.E. (2011). Challenges in the Second Language Acquisition of Derivational Morphology. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, MA. Jackendoff, R. (2002). Foundations of Language. New York: Oxford. Jarmulowicz, L. (2006). School-Aged Children’s Phonological Production of Derived English Words. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 49, 294-308. Jiang, N. (2000). Lexical Representation and Development in a Second Language. Applied Linguistics, 21(1), 47-77. Jiang, N. (2002). Form-meaning Mapping in Vocabulary Acquisition in a Second Language. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 24, 617-637. Lardiere, D. (2006). Knowledge of Derivational Morphology in a Second Language Idiolect. In Proceedings ofthe 8th Generative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition Conference (GASLA2006), ed. Mary GranthamO’Brien, Christine Shea, and John Archibald, 72-79. Somerville, MA:CascadillaProceedings Project. Marchand, H. (1969). The Categories and Types of Present-Day English Word-Formation: A Synchronic-Diachronic Approach. München: C.H. Beck’scheVerlagsbuchhandlung. Tyler, A., & Nagy, W. (1989). The Acquisition of English Derivational Morphology. Journal of Memory and Language, 28, 649-667. Zonneveld, W. (2009). Phonetics and Phonology. Linguistics 1 Course Reader. Utrecht: Utrecht University. Appendix A - Test Fill in the blank In onderstaande zinnen is steeds een woord weggelaten op de positie van de liggende streep. Aan het einde van elke zin zie je een woord staan dat goed past op die plaats, maar dat woord staat nog niet in de juiste vorm. Probeer het woord dat gegeven wordt steeds zo te vervoegen dat het goed in de zin past. Om dat te bereiken moet je bijvoorbeeld van een zelfstandig naamwoord een werkwoord maken, van een bijvoeglijk naamwoord een zelfstandig naamwoord, enzovoort. Er is altijd wel een nieuw woord dat past, en wij zijn heel benieuwd welke keuze je daarvoor maakt. Voorbeeld: 1. The most expensive suite in a luxury hotel is called the ____________ suite. (president) The most expensive suite in a luxury hotel is called the presidential suite. 2. When you have to study a lot of chapters for an exam it can be very ____________ to make a summary. (help) When you have to study a lot of chapters for an exam it can be very to helpful make a summary. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Although not very big, this is a very ____________ chair. (comfort) Even for the best and most faithful workers, there’s always room for __________ .(improve) After a moment of ____________ he accepted the money. (hesitate) Even though he had tried to avoid ____________, everyone cried after his farewell speech. (sentimental) His family was very ____________ of his attempts to become a writer, they really liked what he was trying to do. (support) Times have not been easy for him: I think he deserves more _________ and respect.(tolerant) Before we convinced him, he was quite ____________ to the new proposals. (resist) A tornado can cause ____________ damage. (catastrophe) I don’t mind walking the dog, I actually find it quite ____________ .(enjoy) Schoolchildren sometimes need ____________ consent to participate in fieldtrips. (parent) J.K. Rowling used the character of Voldemort to represent or ___________ evil. (person) Many people came to the ____________ to show their discontent. (demonstrate) He was without doubt the worst ____________ on the show. (contest) Britney Spears made a surprising ____________ in this week’s episode of Glee. (appear) A surgeon obviously needs a lot of ____________ knowledge of the human body.(anatomy) The office workers wanted to ____________ the air in order to create a healthier environment. (humid) The judge concluded that the incident presented to him had been entirely ___________ . (accident) Each time he tries to tell her she may have been making a mistake, she gets very ____________ .(defense) Funny home videos are a great source of ____________ .(entertain) If you place a cup of water in the freezer the water will ___________ and turn into ice. (solid) All eyes were on him as he filled the room with his ____________ presence. (majesty) It was a difficult legal case: the ____________ accused her of murder. (complain) In our work situation we have always stressed the __________ of safety measures. (important) The British Media Awards were hosted by TV ____________ Jo Brand. (personal) Not knowing what to do he called his mother out of ____________ . (desperate) The city centre of Paris contains a lot of ____________ buildings. (monument) Of course, the children only receive ____________ when they have done something really bad. (punish) After a few incidents, the priest tried to ____________ the occasion with prayers. (solemn) She’s has been training a lot recently. Now she’s good at sports and very ________ . (athlete) The teacher told me that my wild behaviour was not____________.(accept) A successful business cannot be run without proper ____________ .(manage) For the family gathering next week she has put together a nice creative _________ . (active) There is another one! I wish there was a more ___________ way to keep spiders out of the house. (effect) The part of Europe without the United Kingdom is known as _________ Europe. (continent) Every morning the teacher checks ___________ figures to see who’s skipping class. (attend) She has been very helpful to me as my ____________ for many years. (assist) He gets bored quite quickly because he has the ____________ span of a flea. (concentrate) Snake is a very ____________ game, you really cannot stop playing it. (addict) Shakespeare talks about the ____________ of truth in his sonnets. (immortal) Everything in this film happens as foreseen. It has a very____________ending.(predict) Appendix B – Responses Secondary School Pupils S = subject Q = question Appendix C – Responses Students of English S = subject Q = question Appendix D – Results Native Speakers Table 10: Results native speakers stress-sensitive Table 11: Results native speakers stress-neutral Appendix E – Responses Native Speakers S = subject Q = question