Breakup of Yugoslavia reading (Pre-AP)

advertisement

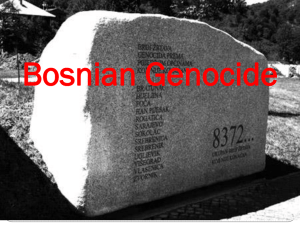

THE BREAK UP OF YUGOSLAVIA Tito's death in 1980 revealed the cracks in the Yugoslavian political system. He was replaced by a collective presidency made up of representatives from each of the republics. However, the nation's economic problems, including a huge foreign debt, began to cause difficulties and the new government proved weak. Both problems facilitated a revival of the ethnic and religious rivalries that were suppressed under Tito. A nationalist movement in Serbia gained control of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia and Slobodan Milosevic, an extreme nationalist, gained power. Milosevic instituted severe measures to support his nationalist cause, including press censorship and the reversal of autonomy for the Kosovo and Vojvodina regions, whose populations were predominantly Albanian and Hungarian, respectively. Milosevic tried to increase the centralization of power and to revive the concept of a Greater Serbia at the same time that Croatian and Slovenian leaders were seeking increased decentralization. As it became clear that Milosevic was intent on increasing Serbian authority, Croatia and Slovenia declared their independence from Yugoslavia in June 1991. Despite a constitutional provision allowing for the secession of republics, the Serbian-dominated Yugoslavian Army actively opposed Croatia's and Slovenia's withdrawal. The independence of Slovenia was conceded after a 10-day war that the Yugoslavian forces lost. However, the large Serb minority in Croatia joined forces with the Yugoslavian Army to gain control of vast territory there. Milosevic had a similar response to the secession of Bosnia and Herzegovina the following year. With their campaign of ethnic cleansing, the Serbs succeeded in killing or forcing out much of the Muslim Bosnian and Croatian populations from large parts of Bosnia. The United Nations (UN) imposed international sanctions against Yugoslavia for its actions. Around the same time, Macedonia also seceded, without much of a struggle, due to its relatively small Serbian population. After losing three wars, Milosevic reconstituted the Yugoslavian government as a two-republic federation including only Serbia and Montenegro. International sanctions against Yugoslavia were eased in 1995 after Milosevic blockaded the Bosnian Serbs in Bosnia and signed the Dayton Agreement, which returned territories to Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia, although there was continued Serbian resistance to the peace plan from within those two countries. Milosevic had been forced to act in part because of the devastation the sanctions had brought to Yugoslavia, with inflation running at unheard-of rates and the state under the threat of disintegration. By early 1998, however, Milosevic had renewed his campaign for a Greater Serbia, this time turning his attention to the predominantly ethnic Albanian region of Kosovo. Though the Serb-controlled Yugoslavian Army was sent into the province ostensibly to root out members of the rebel Kosovo Liberation Army, the military's ethnic cleansing campaign led to numerous civilian deaths, as hundreds of thousands of villagers fled to the mountains and forests for safety. Milosevic's refusal to sign an internationally brokered peace agreement in March 1999 precipitated a North Atlantic Treaty Organization air campaign to crush Serbia's military strength. Following the Serbian retreat from Kosovo, UN peackeepers moved in and assumed administrative control of the region. However, despite the UN presence, ethnic Albanians began a series of violent reprisals against Kosovo's small Serb population. Hoping to extend his hold over the country and take advantage of splintered opposition groups, Milosevic called early elections in September 2000. Although defeated by Vojislav Kostunica, Milosevic initially refused to step down from office, inciting massive protests and demonstrations across the country. Shortly after his defeat, the United States and the European Union (EU) lifted their sanctions against the country. Milosevic was sent to The Hague to face charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including genocide, in relation to his wars against Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia. His trial before a UN tribunal began in 2001 and continued with many delays and suspensions until Milosevic's death in 2006. On March 14, 2002, Serbia and Montenegro signed an EU-brokered accord destroying the Yugoslav federation and forming a new Balkan state. Under the agreement, Serbia and Montenegro became semi-independent states sharing a common foreign and defense policy but maintaining independent economies, customs services, and currencies. The new union of Serbia and Montenegro, approved by the Federal Assembly in June 2002 and officially established in February 2003 by the approval of a new Constitutional Charter (2003) and law to implement it, was intended to keep the states in a loose union for a period of three years, at which time they could reevaluate the agreement and choose to opt out of the union. Montenegrins voted in May 2006 to discontinue the union with Serbia. Accepting the vote, Serbia declared its independence the following month and established diplomatic relations with Montenegro. Also in 2006, the Serbian government and Kosovo's Serb and ethnic Albanian communities began talks over the future status of the province. These talks culminated in a UN proposal for Kosovo's supervised independence, which was rejected by the Serbian government. In the face of this breakdown in negotiations, Kosovo unilaterally declared independence in February 2008 and was recognized by the United States and most of the EU member states. Serbia and Russia denounced the move and blocked UN recognition of the breakaway province. NATO and EU troops stationed in Kosovo virtually ensure its independent existence. In early September 2010 Serbia declared that it would engage in dialogue with Kosovo to resolve the issue, caving to pressure from the EU and other Western governments. Still, Serbia refuses to recognize Kosovo's independence.