Marion Russell

IS HUMANITARIAN INTERVENTION LEGAL IN INTERNATIONAL LAW?

DOES THE LEGAL POSITION NEED TO BE CLARIFIED AND IF SO,

HOW?

Unilateral humanitarian intervention is not legal in international law. Assertions to the

contrary are based on politics, ethics, or wishful thinking. The one process by which

humanitarian intervention can be legal in international law is through Security

Council authorisation. This legality is achieved not by virtue of the definition and

standing of humanitarian intervention itself under international law, but through one

of the two explicit exceptions to the prohibition on the use of force, as outlined in the

Charter of the United Nations. 1 If the Security Council grants authorisation,

humanitarian intervention gains a legal status through this process. If no such

authorisation exists, humanitarian intervention is not legal. In a refreshingly concise

statement on the topic, Corten asserts that due to the clarity in legal texts, the question

at hand is “one of the least complex in contemporary international law”.2

International law on this topic is clear and it is sound. The requirement that an

international body approve humanitarian intervention is a sensible one to prevent

misuse of this justification of the use of force. As Holbrook succinctly puts it, “the

idea that the interveners may determine the legality of a humanitarian intervention

offends a fundamental principle of justice: that one may not be a judge of one’s own

cause”.3 That is not to say that the implementation of the law, as prescribed in the

Charter of the United Nations, General Assembly Resolutions, and International

Court of Justice rulings, is adequate. The power of the veto in Security Council

decision-making is too strong given the unfortunate reality that the political interests

of states contribute to their official positions, even in matters of humanitarian

intervention. Suggestions that the Security Council be expanded to include more

members, and a rule of majority vote be adopted to dilute the extraordinary power of

the veto, are ones that deserve more attention. Security Council reform is perhaps not

1

Charter of the United Nations, 1945, Chapter VII.

Corten, Olivier, The Law Against War: The Prohibition on the Use of Force in Contemporary

International Law, (2010), 497.

3

Holbrook, Jon, ‘Humanitarian Intervention and the Recasting of International Law’ in Chandler, D.

(ed.), Rethinking Human Rights: Critical Approaches to International Politics, (2002), 148.

2

1

Marion Russell

entirely relevant to the matter at hand. The point here is that the focus of debate

should reflect the fact that it is the process, not the law, which requires clarification

and possible amendment.

Aside from the defects of the Security Council approval process, state practice exists

of unilateral intervention where authorisation was either never sought, or was sought

but not granted. Some argue that unauthorised unilateral humanitarian intervention is,

in fact, legal in international law. Others assert that such intervention may not be

legal, but can be mitigated by being referred to as legitimate or justifiable. Both

positions undermine the rule of international law. It must be emphasised that

international law regarding humanitarian intervention is not violated because it is

unclear – it is violated because it can be inconvenient.

Arguments that assert a right of unilateral humanitarian intervention are entirely

unconvincing. Convenient but deeply flawed interpretations of the Charter of the

United Nations are adopted and the plain meaning of the words of the Charter is

ignored. A right of unilateral humanitarian intervention under customary international

law has also been claimed. Adequate state practice and opinio juris simply do not

exist to justify the formation of such a right.

At the other end of the spectrum, assertions that humanitarian intervention violates

state sovereignty and should be outlawed completely overlook the fact that state

sovereignty and human rights coexist in international law texts. Both concepts are

provided for, and regarded as fundamental principles, in the Charter of the United

Nations. State sovereignty and human rights should not be regarded as mutually

exclusive in any way. It must be acknowledged, however, that human rights can no

longer be regarded as an entirely domestic concern. The Security Council has the

power to approve intervention, when human rights violations are occurring, by

adopting a wide but not at all unrealistic reading of the term “international peace and

security”4 which the Security Council is charged to “maintain or restore”.5

4

5

Charter of the United Nations, 1945, Article 39.

Charter of the United Nations, 1945, Article 39.

2

Marion Russell

Discussions that assert that humanitarian intervention can be legitimate but not legal

are unhelpful at best. To add this grey, moral judgement aspect to what should be a

legal debate, undermines the rule of law. It suggests that violation of international law

can be acceptable, that such violations can occupy a space somewhere between

legality and illegality. The clear and absolute position of international law, the power

of reciprocity and adherence to the law is from where international law gains its

power, if it is to have any at all.

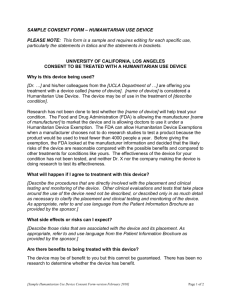

For the purposes of the current paper, the term “humanitarian intervention” will refer

to authorised or unauthorised (unilateral) interference in a foreign state’s affairs that

has the following qualities. Firstly, the interference must involve force, and not just

refer to sanctions and other measures short of the use of force, that can be regarded as

types of interference.6 Humanitarian intervention does not depend on “the consent of

rulers”7 who may in fact be responsible for the humanitarian situation in their state.

Furthermore, if not defined as humanitarian intervention, the action taken would

otherwise be regarded as an aggressive act.8

Humanitarian concerns must be the primary motivation for the action taken.9 Lepard

suggests a more pessimistic but realistic definition regarding the purposes of the

intervention, describing them as “ostensibly humanitarian”. 10 Contrary to some

definitions,11 it is not relevant to which state the individuals to be assisted belong.

They may be nationals of the intervening state or states, or citizens of the ‘target’

state, or any other. Breau asserts that “threatened military actions” as well as actual

6

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2131, Declaration on the Inadmissibility of

Intervention in the Domestic Affairs of States and the Protection of Their Independence and

Sovereignty, (21 December 1965),

7

Cushman, Thomas ‘The Human Rights Case for the War in Iraq: A Consequentialist View’ in

Wilson, Richard Ashby (ed.), Human Rights in the ‘War on Terror’, (2005), 86.

8

Cushman, Thomas ‘The Human Rights Case for the War in Iraq: A Consequentialist View’ in

Wilson, Richard Ashby (ed.), Human Rights in the ‘War on Terror’, (2005), 85.

9

Roth, Kenneth, ‘War in Iraq: Not a Humanitarian Intervention’ in Byers, Michael, War Law:

International Law and Armed Conflict, (2005), 155, Cushman, Thomas ‘The Human Rights Case for

the War in Iraq: A Consequentialist View’ in Wilson, Richard Ashby (ed.), Human Rights in the ‘War

on Terror’, (2005), 86.

10

Lepard, Brian D., Rethinking Humanitarian Intervention: A Fresh Legal Approach Based on

Fundamental Ethical Principles in International Law and World Religions, (2002), 3.

11

Breau, Susan, Humanitarian Intervention: The United Nations & Collective Responsibility, (2005),

29; “A major purpose of the intervention for the intervening state or states is for the protection of

individuals or groups of individuals from their own state”.

3

Marion Russell

military actions fall under the definition of humanitarian intervention. 12 The current

paper will not adopt that position.

Cushman adds the interesting requirement that the action “must be publicly

acknowledged as a humanitarian intervention, and the humanitarian goals must be

specified”.13 It is unclear whether this assertion is not commonly found in definitions

of humanitarian intervention because it is regarded as obvious and intuitive, or

because the explicit identification of humanitarian goals is not in fact a requirement of

such action. Such specification of goals is certainly desirable and may go some way to

clarify and present for scrutiny, the objectives of so-called humanitarian intervention.

Article 2(4)

Article 2(4) of the Charter reads as follows:

All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force

against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other

manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations14

The correct interpretation of this article is the most obvious one; “the use of force

across borders is simply not permitted”.15 This position is supported not only by the

commonsensical reading of the article, but also by the Vienna Convention on the Law

of Treaties as well as the “context, object and purpose” of the Charter.16 Given the

fact that international law draws its strength from such strong and thorough principles,

it is unlikely that this language of the article should be construed in any other way.

Essentially, there exists an “intention to provide a strong and prima facie general

12

Breau, Susan, Humanitarian Intervention: The United Nations & Collective Responsibility, (2005),

29.

13

Cushman, Thomas ‘The Human Rights Case for the War in Iraq: A Consequentialist View’ in

Wilson, Richard Ashby (ed.), Human Rights in the ‘War on Terror’, (2005), 86.

14

Charter of the United Nations, 1945, Article 2(4).

15

Byers, Michael, Simon Chesterman, ‘Changing the rules about rules? Unilateral humanitarian

intervention and the future of international law’ in Holzgrefe, J. L., Robert O. Keohane (eds.),

Humanitarian Intervention: Ethical, Legal, and Political Dilemmas, (2003), 181.

16

Byers, Michael, War Law: International Law and Armed Conflict, (2005), 15.

4

Marion Russell

prohibition on the use of force by States acting otherwise than with the authorization

of the appropriate organ of the United Nations”.17

Despite this, there are those who contend that Article 2(4) does not represent a “flat

prohibition”18 on the use of force or humanitarian intervention.19 Proponents of this

view assert that Article 2(4) attempts to “establish three target prohibitions”,20 rather

than a general prohibition. What follows is the argument that if humanitarian

intervention or any act of force does not 1) breach the territorial integrity of the target

state, or 2) jeopardise the political independence of the target state, or 3) cause

inconsistencies to arise with the Purposes of the United Nations, then it is not an

illegal use of force.

Even if the argument that Article 2(4) establishes three specific prohibitions on the

use of force rather than one general prohibition is accepted, this argument cannot be

used to justify a legal basis for unilateral humanitarian intervention. Surely it is the

case that any type of intervention, by virtue of the very definition of the term

‘intervention’ breaches the territorial integrity of the target state. The same could be

said of the effect on the political independence of that state. The purposes of the

United Nations were to encourage “international peace and security”, and to develop

“friendly relations among nations” and “equal rights”.

21

The three specific

prohibitions on the use of force are, then, in fact quite broad!

Teson argues that “a genuine” humanitarian intervention is not deemed illegal by

Article 2(4) as it does not “result in territorial conquest or political subjugation”.22 In

an ideal world where all actions were honourable and ulterior motives did not exist,

there may be some substance to Teson’s argument. Realistically, it is a naïve position

that encourages a dangerous precedent and begs the question; who gets to decide if a

particular humanitarian intervention is genuine? If “genuine” humanitarian

Brownlie, Ian, ‘Thoughts on Kind-Hearted Gunmen’ in Lillich, Richard B. (ed.), Humanitarian

Intervention and the United Nations (1973), 143.

18

Teson, Fernando R., Humanitarian Intervention: An Inquiry into Law and Morality, (1988), 130.

19

Sellers, Mortimer N. S., Republican Principles in International Law: The Fundamental

Requirements of a Just World Order, (2006), 136.

20

Teson, Fernando R., Humanitarian Intervention: An Inquiry into Law and Morality, (1988), 131.

21

Charter of the United Nations, 1945, Article 1.

22

Teson, Fernando R., Humanitarian Intervention: An Inquiry into Law and Morality, (1988), 131.

17

5

Marion Russell

intervention is simply considered legal, then any state or group of states could claim

that that they are engaging in a genuine humanitarian intervention, valid under Article

2(4), without any independent scrutiny. This level of subjectivity undermines the rule

of law. To eliminate this confusion and the element of subjectivity, intentions are not

considered by Article 2(4) and nor should they be. Article 2(4) is an international

legal text defining legal rights and obligations. As such it derives its power from

having a clear stance that allows for very little subjectivity. The Preamble of the

Charter affirms that member states of the United Nations will “ensure, by the

acceptance of principles and the institution of methods, that armed force shall not be

used, save in the common interest”.23 That common interest is not to be determined

by one state, but rather an international representative body; the Security Council.

At San Francisco in 1945, France “proposed an amendment to the draft Charter” that

would effectively allow unilateral humanitarian intervention when human rights

abuses occurred. The proposal was rejected on the grounds that it was, “too broad and

vague an exception to Article 2(4)’s core ‘no violence’ principle. As an exception to

that rule, it lacked clear standards and procedures for deciding who might invoke it

and in what circumstances”.24 A clear and absolute position was clearly the planned

interpretation of Article 2(4). The language of the text supports this, as Gray points

out, the expression “use of force” and not “war” was employed in order to expand the

prohibition as much as possible.25

In examining the travaux preparatoires of the Charter, Teson believes that the

intuitive position would be that humanitarian intervention would not have been

contrary to the intentions of those who composed the Charter of the United Nations;

“fresh memories from the Holocaust would have led the framers to allow for

humanitarian intervention, had they thought about it”.26 Equally, however, it must not

be forgotten that Hitler justified some of his actions under the premise of

23

Charter of the United Nations, 1945, Preamble.

Franck, Thomas M., ‘Interpretation and Change in the Law of Humanitarian Intervention’ in

Holzgrefe, J. L., Robert O. Keohane (eds.), Humanitarian Intervention: Ethical, Legal, and Political

Dilemmas, (2003), 207.

25

Gray, Christine, ‘The Charter Limitations on the Use of Force: theory and Practice’ in Lowe,

Vaughan, Adam Roberts, Jennifer Welsh, Dominik Zaum (eds.), The United Nations Security Council

and War: The Evolution of Thought and Practice since 1945, (Oxford University Press, 2008), 86.

26

Teson, Fernando R., Humanitarian Intervention: An Inquiry into Law and Morality, (1988), 135.

24

6

Marion Russell

humanitarian intervention regarding “atrocities against native German peoples in the

Sudetenland portion of Czechoslovakia.” 27 The opportunity for misuse of the term

‘humanitarian intervention’ cannot be underestimated.

The Exceptions

There are two exceptions to the prohibition on the use of force. Article 51 of the

Charter outlines the right of self-defence, the first exception:

Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective

self-defence if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the

Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and

security. Measures taken by Members in the exercise of this right of self-defence shall be

immediately reported to the Security Council and shall not in any way affect the authority

and responsibility of the Security Council under the present Charter to take at any time

such action as it deems necessary in order to maintain or restore international peace and

security.28

The second exception, as outlined in Chapter VII, Article 42 in particular, gives the

Security Council sole right to take or authorise measures using force:

Should the Security Council consider that measures provided for in Article 41 would be

inadequate or have proved to be inadequate, it may take such action by air, sea, or land

forces as may be necessary to maintain or restore international peace and security. Such

action may include demonstrations, blockade, and other operations by air, sea, or land

forces of Members of the United Nations.29

Although this is where the power to authorise the use of force is derived, the idea that

it is the Security Council that is responsible for all matters pertaining to peace and

security, and the encouragement or enforcement thereof, is mentioned several times in

27

May, Larry, Aggression and Crimes against Peace, (2008), 276.

Charter of the United Nations, 1945, Article 51.

29

Charter of the United Nations, 1945, Article 42.

28

7

Marion Russell

the Charter.30 Orford declares that the fact that “the Security Council is invested with

coercive power”31 is what distinguishes it from other international structures.

While it is the central thesis of this paper that humanitarian intervention is not legal in

international law, it must be acknowledged that the Charter does not explicitly and

specifically rule it out. Essentially, it is so clearly a use of force that it does not

require particular mention in the general prohibition on the use of force in Article

2(4). Furthermore, from the existence of the two exceptions mentioned above, it is

clear that, if the composers of the Charter had meant to allow for humanitarian

intervention, they would have explicitly and specifically ruled it in. Self-defence, for

example, is an exception to the prohibition of the use of force. It has its own article in

the Charter to convey this. If humanitarian intervention had the same standing, would

it not also have its own article declaring it to be an exception to the prohibition on the

use of force?

The conclusion that must be reached here is that humanitarian intervention is not an

exception to Article 2(4). The only way it can be legal, then, is if it constitutes part of

one of the approved exceptions. The purposes of humanitarian intervention (which

form an essential aspect of its very definition) are not compatible with those of selfdefence. There is no such tension regarding the other exception, however. If the

Security Council sees fit to authorise a use of force primarily due to humanitarian

concerns, then humanitarian intervention is legal in that particular circumstance.

Unilateral Humanitarian Intervention

Unilateral humanitarian intervention has no legal basis in international law. Those

who argue otherwise are employing wishful thinking in the reading of legal texts, and

overzealous interpretations regarding state practice and opinio juris in the formation

of customary international law. Others assert an implicit right of unilateral

Charter of the United Nations, 1945, Article 24: “In order to ensure prompt and effective action by

the United Nations, its Members confer on the Security Council primary responsibility for the

maintenance of international peace and security, and agree that in carrying out its duties under this

responsibility the Security Council acts on their behalf”, Article 53, Article 54.

31

Orford, Anne, Reading Humanitarian Intervention: Human Rights and the Use of Force in

International Law, (2003), 2.

30

8

Marion Russell

humanitarian intervention due to the Security Council’s unwillingness or failure to act

on many occasions. General Assembly Resolutions as well as International Court of

Justice rulings support the position that there remains no right of unilateral

humanitarian intervention in international law.32

There is no text in international law that declares a right of humanitarian intervention.

As has been discussed, a curious interpretation of Article 2(4), with very little

intuitive or historical support, has been propagated announcing that humanitarian

intervention is not considered in the text of Article 2(4). It is clear from an

examination of the documented exceptions to the prohibition on the use of force,

however, that if a legal right of humanitarian intervention had been intended, it would

have been explicitly included in the Charter, rather than subtly excluded.

In order to avoid these unconvincing interpretations of clear articles of the Charter,

some proponents of unilateral humanitarian intervention assert that there is a legal

basis in customary international law for allowing unilateral humanitarian intervention.

While it is true that some state practice to this effect does exist, states have been, for

the most part, “reluctant” to assert a positive right of humanitarian intervention in

international law, thereby preventing the formation of opinio juris; an essential

requirement of any customary international law. 33 This is because the law is not

ambiguous. State practice of unilateral humanitarian intervention exists because the

law deeming it to be illegal is inconvenient, not because it is unclear. Byers and

Chesterman believe that arguments in favour of a customary international law right of

unilateral humanitarian intervention are irrelevant anyway as “clear treaty provisions

prevail over customary international law”.34

32

Case Concerning Military and Paramilitary Activities in and Against Nicaragua, (Nicaragua v.

United States of America) ICJ Reports 1986, 18., Corfu Channel Case (United Kingdom v. Albania)

ICJ Reports, 1949, 35.

33

Corten, Olivier, The Law Against War: The Prohibition on the Use of Force in Contemporary

International Law, (2010), 497.

34

Byers, Michael, Simon Chesterman, ‘Changing the rules about rules? Unilateral humanitarian

intervention and the future of international law’ in Holzgrefe, J. L., Robert O. Keohane (eds.),

Humanitarian Intervention: Ethical, Legal, and Political Dilemmas, (Cambridge University Press,

2003), 182.

9

Marion Russell

Article 2(4) is regarded by many as jus cogens. 35 Judge Sette-Camera argued in

favour of non-intervention being regarded as jus cogens in a separate opinion in the

Case Concerning Military and Paramilitary Activities in and Against Nicaragua.36 If

Article 2(4) is to be regarded as jus cogens, not only does it follow that customary

international law would not be sufficient to displace the contents of the article, but it

also makes it extremely unlikely that any subtle oversights or inclusions should be

allowed to be argued as no derogation from the words or Article 2(4) would be

permitted.

37

Breau contends, however, that there is uncertainty regarding the

interpretation of Article 2(4) and, therefore, its potential jus cogens status. In support

of this limited application of the jus cogens status, Breau argues that only aggressive

uses of force are covered by jus cogens as was propagated by the International Law

Commission; “the use of force could only violate jus cogens when it served conquest

or forcible annexation, in other words constituted aggression.”38 Examinations of the

potential for a customary international law right of unilateral humanitarian

intervention are relevant while the jus cogens status of Article 2(4) is unresolved.

Customary International Law

Hehir asserts that, based on an analysis of state interference both before and after

1945, “humanitarian intervention does not have a place in customary international

law”. 39 This is because there were, firstly, no “genuine” cases of humanitarian

intervention and, secondly, no “unambiguous” opinio juris.40 The cases that are most

often cited in examinations of customary international law on this topic are India’s

intervention in East Pakistan in 1971, Vietnam’s intervention in Cambodia in 1978,

Tanzania’s intervention in Uganda in 1979, and the intervention in Iraq by Britain,

35

Alston, Philip, Euan Macdonald (eds.), Human Rights, Intervention, and the Use of Force, (2008), 7.

Case Concerning Military and Paramilitary Activities in and Against Nicaragua, (Nicaragua v.

United States of America) ICJ Reports 1986, 18.

37

Hehir, Aidan, Humanitarian Intervention after Kosovo: Iraq, Darfur and the Record of Global Civil

Society, (2008), 15: “Articles 53 and 64 of the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties states

that this particular provision is part of jus cogens.”

38

Ud Doc. Report of the International Law Commission on the work of its thirty-second session,

GAOR 35th session, Supp. No. 10 A/35/10 pp91-95, 105-108 summarised in Breau, Susan,

Humanitarian Intervention: The United Nations & Collective Responsibility, (2005), 256.

39

Hehir, Aidan, Humanitarian Intervention after Kosovo: Iraq, Darfur and the Record of Global Civil

Society, (2008), 23.

40

Hehir, Aidan, Humanitarian Intervention after Kosovo: Iraq, Darfur and the Record of Global Civil

Society, (2008), 24.

36

10

Marion Russell

France, Italy, the Netherlands, and the United States in 1991.41 In these cases, there is

a “near absence of opinio juris”42 supporting a legal right of unilateral humanitarian

intervention. The cases most likely to support the formation of customary

international law, then, fail to do so. Most commonly, intervening states justified their

actions on the basis of a clearly legal exception to Article 2(4); that of self-defence.43

It must be concluded that “it would be premature to argue the existence of a new rule

of customary international law”.44

Furthermore, there is, in fact, substantial evidence of opinio juris to the contrary;

supporting the position that unilateral humanitarian intervention is not legal in

international law. The very fact that states do continue to seek Security Council

authorization for humanitarian intervention suggests that they recognize the legal

obligation to do so. In an attempt to justify the intervention in Kosovo, UK Foreign

and Commonwealth Office in 1998 stated that the fact that the Security Council

authorized humanitarian intervention in Bosnia and Somalia demonstrated that

‘Security Council authorisation to use force for humanitarian purposes is now widely

accepted’ and that ‘force can also be justified on the grounds of overwhelming

humanitarian necessity without a UN Security Council Resolution’.”45 The conclusion

reached is quite a stretch from reality. What in fact is proved is that the Security

Council not only continues to be the mandatory legal process by which intervention

may be approved, but it is also recognised and acknowledged as such. The process of

Security Council authorization may be flawed but it is not seen as outdated, irrelevant,

or in need of replacement by unsubstantiated claims of a contrary customary

international law. A resolution based on humanitarian intervention has been approved

just a few months ago regarding the situation in Libya.46 If there existed a widespread

belief that unilateral humanitarian intervention were legal, states would not go to the

trouble of having matters considered by the Security Council.

41

Byers, Michael, War Law: International Law and Armed Conflict, (2005), 92.

Byers, Michael, War Law: International Law and Armed Conflict, (2005), 92.

43

Byers, Michael, War Law: International Law and Armed Conflict, (2005), 97., Janzekovic, John, The

Use of Force in Humanitarian Intervention, (2006), 141.

44

Breau, Susan, Humanitarian Intervention: The United Nations & Collective Responsibility, (2005),

269.

45

Quoted in Hehir, Aidan, Humanitarian Intervention after Kosovo: Iraq, Darfur and the Record of

Global Civil Society, (2008), 21.

46

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973, The Situation in Libya, (2011)

42

11

Marion Russell

Expressions of opinio juris disputing a legal basis (in international law or customary

international law) for unilateral humanitarian intervention are evident since the

inception of the Charter. In response to the NATO intervention in Kosovo, the “133

states comprising the G-77 declared, ‘We reject the so-called “right” of humanitarian

intervention, which has no legal basis in the United Nations charter or in the general

principles of international law’.”47

Even regarding genocide, respect for the clear international law regarding

humanitarian intervention is evident. At the Sixth Committee of the General

Assembly, attendees considered whether intervention to prevent genocide in a foreign

state would constitute aggression; “many of the delegates said that it would”.48 The

French Prime Minister at the time said of the humanitarian intervention in Rwanda,

“[This is a] humanitarian operation intended to save threatened populations [, and it is

subject to a] number of conditions or specific principles governing this humanitarian

intervention. First principle: France will only act with a mandate from the UN

Security Council. The Government considered that action of this type, responding to a

humanitarian duty, ought despite its urgency to be authorized by the international

community”.49 In light of these comments, to convincingly argue for the existence of

opinio juris in favour of a legal right under customary international law for unilateral

humanitarian intervention, is near impossible.

It has so far been established that unilateral humanitarian intervention has no basis in

legal texts or in customary international law. An even more flimsy argument in favour

of the legality of unilateral humanitarian intervention proclaims that there is an

implicit right to such intervention when the Security Council is unwilling or unable to

intervene in situations of humanitarian crisis. It is entirely counterintuitive to suppose

that the legal right regarding something as fundamental as the use of force could be

implicitly granted. Very little attention will be devoted to this justification due to its

lack of valid basis in international law. It is described as a “holistic” approach that is

“not in compliance with the specific provisions on the use of force but is within the

47

Quoted in Hehir, Aidan, Humanitarian Intervention after Kosovo: Iraq, Darfur and the Record of

Global Civil Society, (2008), 24.

48

Brownlie, Ian, International Law and the Use of Force by States, (1963), 340-341.

49

Quoted in Alston, Philip, Euan Macdonald (eds.), Human Rights, Intervention, and the Use of Force,

(2008), 93.

12

Marion Russell

spirit of the Charter taken as a whole.”50As has been propagated by this paper, such

positions that encourage subjectivity rather than adherence to clear and strict legal

texts, only serve to undermine international law.

Lillich argues that “when the Security Council is unable to fulfill its responsibilities

by taking enforcement action under Chapter VII the prohibiting provision of Article

2(4) is suspended”.51 This is an astonishing position that suggests that the Security

Council authorization process is meaningless if force is going to be employed

regardless of the will of the Security Council. The fact that the Security Council

authorization process is inadequate is not disputed. That there is any basis in

international law for taking matters into your own hands when the official system is

seen as ineffective, however, is indefensible. The Danish Institute of International

Affairs dispelled Lillich’s theory; “it is not legally sound to assert that the Charter

must be suspended when the Security Council fails to act as there is simply no legal

basis for this assertion.“52

State Sovereignty and Human Rights

The description of humanitarian intervention as a “condoned anomaly in international

law” 53 due to the “competing” aspects of international law that it attempts to

reconcile, overlooks the fact that state sovereignty and human rights are both

principles key to the Charter of the United Nations. As such, they are intended to, and

must be able to, coexist. The fact that there is no right of unilateral humanitarian

intervention in international law serves to limit potential tension between these two

concepts. That humanitarian intervention must be subjected to scrutiny and

deliberation by the Security Council, in theory, ensures that state sovereignty shall be

upheld at all times unless a threat to international peace and security is identified.

McDougal, Myers and W. Michael Reisman, ‘Response’ in 3 International Lawyer 438 (1969), 444.

Lillich, Richard B. (1967) ‘Forcible Self-help by States to Protect Human Rights’, Iowa Law Review,

vol. 53, 34.

52

DIIA paraphrased in Hehir, Aidan, Humanitarian Intervention after Kosovo: Iraq, Darfur and the

Record of Global Civil Society, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 23.

53

Bagaric, Mirko, Future Directions in International Law and Human Rights, (Sandstone Academic

Press, 2007), 143.

50

51

13

Marion Russell

Article 2(7) affirms that:

Nothing contained in the present Charter shall authorize the United Nations to intervene in

matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state or shall require

the Members to submit such matters to settlement under the present Charter; but this

principle shall not prejudice the application of enforcement measures under Chapter Vll54

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2131 Declaration on the Inadmissibility

of Intervention in the Domestic Affairs of States and the Protection of Their

Independence and Sovereignty also addresses the issue of state sovereignty and the

principle of non-intervention:

No State has the right to intervene, directly or indirectly, for any reason whatever in the

internal or external affairs of any other state. Consequently, armed intervention and all

other forms of interference or attempted threats against the personality of the State or

against its political, economic, or cultural elements are condemned55

This interpretation of non-intervention was confirmed in United Nations General

Assembly Resolution 2625 Declaration on Principles of International Law

Concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation Among States.56 These documents,

as well as the Charter contain the “critical”57 qualification that Chapter VII and the

Security Council’s mandate regarding the maintenance and enforcement of

international peace and security be upheld. In this way, although all forms of

intervention, “for any reason whatever”58 are deemed unlawful, the one exception of

Security Council authorized force (and therefore a legal right of humanitarian

intervention) is preserved.

54

Charter of the United Nations, 1945, Article 2(7).

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2131, Declaration on the Inadmissibility of

Intervention in the Domestic Affairs of States and the Protection of Their Independence and

Sovereignty, (21 December 1965), 1.

56

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2625, Declaration on Principles of International Law

concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation among States in accordance with the Charter of the

United Nations, (24 October 1970), Preamble.

57

Breau, Susan, Humanitarian Intervention: The United Nations & Collective Responsibility, (2005),

231.

58

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2131, Declaration on the Inadmissibility of

Intervention in the Domestic Affairs of States and the Protection of Their Independence and

Sovereignty, (21 December 1965), 1.

55

14

Marion Russell

Some have argued that the interpretation of what constitutes a threat to international

peace and security has been “questionably broadened”.59 The authority of the Security

Council to authorise action that impinges upon a state’s sovereignty hinges on the fact

that human rights are no longer considered as exclusively within the domestic

jurisdiction of states. Violations of human rights can, therefore, be interpreted as

constituting threats to international peace and security, thereby engaging Chapter VII

of the Charter, and legal humanitarian intervention.

It is true that those who composed the Charter “probably did not contemplate

situations of humanitarian emergency resulting from civil war or repression,”60 but

that is no reason to ignore the reality that internal, intra-state conflicts now vastly

outnumber inter-state conflicts, and the government of a state may itself be the

perpetrator of human rights abuses on its own citizens. There is no evidence that any

situations beyond inter-state conflict were considered in the framing of the Charter. 61

There has, however, been an “evolution in practice from an emphasis on what states

do to each other to what states do to their own citizens.”62

While some may have difficulty appreciating how an internal conflict or human rights

abuses could affect international peace and security,63 it must be appreciated that a

wide interpretation of ‘international peace and security’ does not mean that the word

‘international’ simply needs to be ignored or seen as superfluous as some may

argue.64 Without delving into semantic arguments or simply ignoring a key term, it is

entirely reasonable to assume that ‘international peace and security’ can be threatened

by conflicts that are otherwise seemingly contained within one state.

59

Hehir, Aidan, Humanitarian Intervention after Kosovo: Iraq, Darfur and the Record of Global Civil

Society, (2008), 20.

60

Breau, Susan, Humanitarian Intervention: The United Nations & Collective Responsibility, (2005),

236-237.

61

Danish Institute of International Affairs, Humanitarian Intervention, 1999, 62.

62

Breau, Susan, Humanitarian Intervention: The United Nations & Collective Responsibility, (2005),

21, See also Stacy, Helen M., Human Rights for the 21st Century, (2009), 79: “governments … may

send their human rights troubles abroad. Violent or careless governments may create opportunities for

terrorists to train and organize across borders, and criminals may take advantage of a breakdown in

order to export illegal drugs to neighbouring countries or traffic women and children for prostitution.“

63

Holbrook, Jon, ‘Humanitarian Intervention and the Recasting of International Law’ in Chandler, D.

(ed.), Rethinking Human Rights: Critical Approaches to International Politics, (2002), 143-144.

64

Holbrook in Chandler p 145

15

Marion Russell

A wide reading of situations that constitute a threat to international peace and security

is convenient in that it allows for a legal basis for humanitarian intervention, but it is

also the realistic and appropriate reading of the mandate given to the Security Council

through Chapter VII of the Charter. Humanitarian crises resulting from human rights

violations can be regarded as threats to international peace and security for two

reasons. Firstly, human rights have been “internationalised” by the existence of

human rights treaties.65 Secondly, many “spill-over” effects can occur as a result of

conflicts or situations that otherwise seem entirely intra-state. Refugees,

destabilisation of regions and terrorist threats can constitute a threat to international

peace and security.66

Legitimate but not Legal

The claim that humanitarian intervention can be legitimate even if it is not legal is rife

among so-called legal assessments of humanitarian intervention. The assertion of this

paper is that such discussions should be confined to moral and political spheres of

debate. In addition to complicating legal discussions, the claim is damaging to the rule

of international law and establishes dangerous precedents by way of “sensible

exceptions”.67

While it is hoped that law reflects intuitive values and beliefs, if it does not appear to

do so, the law itself or its implementation should be examined and possibly amended

through the appropriate processes. To simply ignore the legal position, to sweep it

aside when it is not convenient, sets a dangerous precedent and undermines the rule of

international law. Law does not draw its strength from being adhered to and

implemented selectively, when it is convenient. The idea that morally “right”

unilateral humanitarian intervention can be seen to hover somewhere between legality

65

Pease, Kelly-Kate S., International Organizations: Perspectives on Governance in the Twenty-First

Century, (2000), 265., Garrett, Stephen A., Doing Good and Doing Well: An Examination of

Humanitarian Intervention, (1999), 47.

66

Breau, Susan, Humanitarian Intervention: The United Nations & Collective Responsibility, (2005),

240.

67

Franck, Thomas M., ‘Interpretation and Change in the Law of Humanitarian Intervention’ in

Holzgrefe, J. L., Robert O. Keohane (eds.), Humanitarian Intervention: Ethical, Legal, and Political

Dilemmas, (2003), 231.

16

Marion Russell

and illegality detracts from what is actually a clear legal position on the subject and

“mitigation and acceptance in principle are not always easy to distinguish”.68

In a legal debate, an act is either legal or illegal. Interpretation of legal texts, state

practice, and opinio juris may contribute to that decision. This clarity is a strength of

international law. Adding an ethical or political aspect to this debate takes it wholly

out of the legal realm. Discussions of the legality of humanitarian intervention in

international law are littered with terms such as legitimate, justifiable, exceptional

illegality, moral necessity, tolerated, retroactively validated, and technical

noncompliance. These terms should be clearly defined as only relevant to moral

arguments and kept quite separate from discussions of legality.

Most often described as ‘legitimate but not legal’ is NATO’s intervention in

Kosovo. 69 To ignore international law in favour of adopting moral validation is a

short-sighted and dangerous position. Instead of adding a new and complex aspect to

the debate regarding the legality of humanitarian intervention, a more sensible

response in such situations would be to examine why the proper process (Security

Council authorisation) was not effective.

It has been argued that, “NATO’s intervention in Kosovo should be treated as an ad

hoc exception rather than a precedent for establishing a new rule allowing for

unilateral uses of force.” 70 This naïve comment ignores the fact that precedent is

automatically and necessarily set by such actions. Simma admits that “recognizing a

right of unilateral humanitarian intervention would lead to abuse” and so “such uses

of force should remain illegal but that the law should turn a blind eye to breaches in

particular cases, such as Kosovo.”71 International law simply does not function on the

assumption that sometimes a blind eye can or must be turned to certain ‘legitimate’

violations of international law. Roberts describes the legitimate but illegal approach

Brownlie, Ian, ‘Thoughts on Kind-Hearted Gunmen’ in Lillich, Richard B. (ed.), Humanitarian

Intervention and the United Nations (1973), 146.

69

Pattison, James, Humanitarian Intervention and the Responsibility to Protect: Who Should

Intervene?, (2010), 44.

70

Roberts, Anthea, ‘Legality Versus Legitimacy: Can Uses of Force be Illegal but Justified?’ in Alston,

Philip, Euan Macdonald (eds.), Human Rights, Intervention, and the Use of Force, (2008), 179.

71

Paraphrased in Roberts, Anthea, ‘Legality Versus Legitimacy: Can Uses of Force be Illegal but

Justified?’ in Alston, Philip, Euan Macdonald (eds.), Human Rights, Intervention, and the Use of

Force, (2008), 179.

68

17

Marion Russell

as an, “intuitively attractive way of maintaining the prohibition on unilateral uses of

force while permitting justice in individual cases”.72 While the clear prohibition on

the use of force and unilateral intervention remains intact, it is in danger of being

undermined by the ‘legitimate but illegal’ approach. Roberts concludes that this

approach “does not maintain the integrity of the general prohibition on the use of

force.” 73 Declaring the existence of an absolute prohibition is meaningless if

exceptions are morally, politically, or in any other way accepted and international law

is swept aside.

Does the Legal Position Need to be Clarified?

Essentially, the legal position regarding humanitarian intervention is simple;

humanitarian intervention is legal if Security Council authorisation has been granted.

The legal position regarding humanitarian intervention does not need to be clarified.

Just because a law is broken, misused, or ignored at times, this does not necessarily

lead to the conclusion that the law in question is unclear, rather it may simply mean

that the law is in some circumstances, inconvenient.

As has been demonstrated, arguments that attempt to define a valid basis in

international law for unilateral humanitarian intervention, are flawed and

unconvincing. Byers and Chesterman outline the convincing assertion that if “states

were to admit – explicitly or implicitly – that they were violating international law,

the effect would be to strengthen, rather than weaken, the rules governing

intervention”74. Accordingly, international law is left intact and the issue becomes one

of enforcement; “The greatest threat to an international rule of law lies not in the

occasional breach of that law – laws are frequently broken in all legal systems,

Roberts, Anthea, ‘Legality Versus Legitimacy: Can Uses of Force be Illegal but Justified?’ in Alston,

Philip, Euan Macdonald (eds.), Human Rights, Intervention, and the Use of Force, (2008), 180.

73

Roberts, Anthea, ‘Legality Versus Legitimacy: Can Uses of Force be Illegal but Justified?’ in Alston,

Philip, Euan Macdonald (eds.), Human Rights, Intervention, and the Use of Force, (2008), 184.

74

Byers, Michael, Simon Chesterman, ‘Changing the rules about rules? Unilateral humanitarian

intervention and the future of international law’ in Holzgrefe, J. L., Robert O. Keohane (eds.),

Humanitarian Intervention: Ethical, Legal, and Political Dilemmas, (2003), 198.

72

18

Marion Russell

sometimes for the best of reasons – but in attempts to mold that law to accommodate

the shifting practices of the powerful.”75

When the law, clear as it is, is acknowledged as such, it will gain respect and

persuasive power. Kenneth Roth agrees that while there is confusion and controversy

regarding the legal standing of unilateral humanitarian intervention, abuse of the

justification for the use of force will continue.

A necessary and significant distinction that must be made is between law and the

implementation of the terms of that law. The current paper calls for a redefining of the

parameters of the debate regarding unilateral humanitarian intervention in

international law. While states side-step around the law and find necessarily

subjective, moral justifications for their actions, or attempt to find a legal basis for

unilateral humanitarian intervention, the issue that should be debated, is how the

Security Council authorisation process could be improved. Suggestions here include

weakening the power of the veto, increasing the number of Security Council

members, and employing a majority vote; a topic for another paper entirely. As

Brownlie puts it, “The objective is, of course, shared by all: to prevent genocide,

degradation of subject populations, and so on. However, as with other areas, such as

the concept of development, it is the vehicle for attaining the shared objective that is

the matter of controversy.”76

There is one sole mechanism by which humanitarian intervention is legal in

international law; that is, by Security Council authorisation. Moral and political

arguments aside, a Security Council authorisation produces legal humanitarian

intervention. Unilateral humanitarian intervention, however, is never legal in

international law. This position must be maintained as it is, “intended to keep out of

circulation disastrously vague and unworkable principles of self-limitation.”77

Byers, Michael, Simon Chesterman, ‘Changing the rules about rules? Unilateral humanitarian

intervention and the future of international law’ in Holzgrefe, J. L., Robert O. Keohane (eds.),

Humanitarian Intervention: Ethical, Legal, and Political Dilemmas, (2003), 203.

76

Brownlie, Ian, ‘Thoughts on Kind-Hearted Gunmen’ in Lillich, Richard B. (ed.), Humanitarian

Intervention and the United Nations (1973), 148.

77

Brownlie, Ian, ‘Thoughts on Kind-Hearted Gunmen’ in Lillich, Richard B. (ed.), Humanitarian

Intervention and the United Nations (1973), 145.

75

19

Marion Russell

Those who oppose this plain interpretation of the law grasp at invalid legal arguments

– convoluted interpretations of Article 2(4), or an unestablished legal right under

customary international law. Others sweep the law aside and argue that unilateral

humanitarian intervention is legitimate even if it is not legal. While flawed legal

arguments undermine the rule of international law, the ‘legitimate but not legal’

argument may be more damaging to the rule of law. It portrays an unlawful act as

acceptable and demonstrates that a loophole can be exercised through this moral

interpretation. “In general, while international law may be in flux about humanitarian

intervention, legal scholars have not followed their colleagues in political and moral

philosophy in urging wholesale changes in what appear to be straightforward

applications of jus ad bellum concepts.”78

Moral and political considerations should not feature so prominently in discussions of

humanitarian intervention in international law. The fact is that the status of

humanitarian intervention in international law is clear. While it can at times be

convenient to establish controversy and suggest uncertainty in the law, if progress is

to be made in establishing a more adequate system of Security Council approval of

humanitarian intervention, the clear legal position will have to be acknowledged.

78

May, Larry, Aggression and Crimes against Peace, (Cambridge University Press, 2008), 278.

20

Marion Russell

Abiew, Francis Kofi, The Evolution of the Doctrine and Practice of Humanitarian

Intervention, (Kluwer Law International, 1999)

Alston, Philip, Euan Macdonald (eds.), Human Rights, Intervention, and the Use of

Force, (Oxford University Press, 2008)

Bagaric, Mirko, Future Directions in International Law and Human Rights,

(Sandstone Academic Press, 2007)

Breau, Susan, Humanitarian Intervention: The United Nations & Collective

Responsibility, (Cameron May, 2005)

Brownlie, Ian, International Law and the Use of Force by States, (Oxford University

Press, 1963)

Brownlie, Ian, ‘Thoughts on Kind-Hearted Gunmen’ in Lillich, Richard B. (ed.),

Humanitarian Intervention and the United Nations (University Press of Virginia,

1973)

Byers, Michael, War Law: International Law and Armed Conflict, (Atlantic Books,

2005)

Byers, Michael, Simon Chesterman, ‘Changing the rules about rules? Unilateral

humanitarian intervention and the future of international law’ in Holzgrefe, J. L.,

Robert O. Keohane (eds.), Humanitarian Intervention: Ethical, Legal, and Political

Dilemmas, (Cambridge University Press, 2003)

Chesterman, Simon, Just War or Just Peace? Humanitarian Intervention and

International Law, (Oxford University Press, 2001)

Corten, Olivier, ‘Human Rights and Collective Security: Is There an Emerging Right

of Humanitarian Intervention?’ in Alston, Philip, Euan Macdonald (eds.), Human

Rights, Intervention, and the Use of Force, (Oxford University Press, 2008)

Corten, Olivier, The Law Against War: The Prohibition on the Use of Force in

Contemporary International Law, (Hart Publishing, 2010)

Danish Institute of International Affairs, Humanitarian Intervention, 1999

Farer, Tom J., ‘Humanitarian Intervention before and after 9/11: Legality and

Legitimacy’ in Holzgrefe, J. L., Robert O. Keohane (eds.), Humanitarian

Intervention: Ethical, Legal, and Political Dilemmas, (Cambridge University Press,

2003)

Franck, Thomas M., ‘Interpretation and Change in the Law of Humanitarian

Intervention’ in Holzgrefe, J. L., Robert O. Keohane (eds.), Humanitarian

Intervention: Ethical, Legal, and Political Dilemmas, (Cambridge University Press,

2003)

21

Marion Russell

Garrett, Stephen A., Doing Good and Doing Well: An Examination of Humanitarian

Intervention, (Praeger Publishers, 1999)

Gray, Christine, ‘The Charter Limitations on the Use of Force: theory and Practice’ in

Lowe, Vaughan, Adam Roberts, Jennifer Welsh, Dominik Zaum (eds.), The United

Nations Security Council and War: The Evolution of Thought and Practice since

1945, (Oxford University Press, 2008)

Greenstock, Jeremy, ‘The Security Council in the Post-Cold War World’, in Lowe,

Vaughan, Adam Roberts, Jennifer Welsh, Dominik Zaum (eds.), The United Nations

Security Council and War: The Evolution of Thought and Practice since 1945,

(Oxford University Press, 2008)

Greenwood, Christopher, ‘International Law and the NATO Intervention in Kosovo’

in 49 ICLQ 926 (2000)

Hehir, Aidan, Humanitarian Intervention after Kosovo: Iraq, Darfur and the Record

of Global Civil Society, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008)

Holbrook, Jon, ‘Humanitarian Intervention and the Recasting of International Law’ in

Chandler, D. (ed.), Rethinking Human Rights: Critical Approaches to International

Politics, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2002)

Holzgrefe, J. L., Robert O. Keohane (eds.), Humanitarian Intervention: Ethical,

Legal, and Political Dilemmas, (Cambridge University Press, 2003)

Institute of International Law, Resolution on a protection des droits de l’homme et le

principe de non-intervention dans les affaires des Etats, (13 September 1989)

Janzekovic, John, The Use of Force in Humanitarian Intervention, (Ashgate, 2006)

Krisch, Nico, ‘The Security Council and the Great Powers’ in Lowe, Vaughan, Adam

Roberts, Jennifer Welsh, Dominik Zaum (eds.), The United Nations Security Council

and War: The Evolution of Thought and Practice since 1945, (Oxford University

Press, 2008)

Lepard, Brian D., Rethinking Humanitarian Intervention: A Fresh Legal Approach

Based on Fundamental Ethical Principles in International Law and World Religions,

(The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2002)

Lillich, Richard B. (1967) ‘Forcible Self-help by States to Protect Human Rights’,

Iowa Law Review, vol. 53

Lillich, Richard B., Hurst Hannum (eds.), International Human Rights: Problems of

Law, Policy and Practice, (Little, Brown and Company, 1995)

May, Larry, Aggression and Crimes against Peace, (Cambridge University Press,

2008)

22

Marion Russell

McDougal, Myers and W. Michael Reisman, ‘Response’ in 3 International Lawyer

438 (1969)

Orford, Anne, Reading Humanitarian Intervention: Human Rights and the Use of

Force in International Law, (Cambridge University Press, 2003)

Pattison, James, Humanitarian Intervention and the Responsibility to Protect: Who

Should Intervene?, (Oxford University Press, 2010)

Pease, Kelly-Kate S., International Organizations: Perspectives on Governance in the

Twenty-First Century, (Pearson Prentice Hall, 2000)

Roberts, Adam, ‘Nato’s Humanitarian War over Kosovo’, Survival, 41, no. 3 (1999):

pp 102-23.

Roberts, Anthea, ‘Legality Versus Legitimacy: Can Uses of Force be Illegal but

Justified?’ in Alston, Philip, Euan Macdonald (eds.), Human Rights, Intervention, and

the Use of Force, (Oxford University Press, 2008)

Robertson, Geoffrey, Crimes against Humanity: The Struggle for Global Justice,

(Ringwood, 1999)

Sarooshi, Dan, ‘The Security Council’s Authorization of Regional Arrangements to

Use Force: The case of NATO’, in Lowe, Vaughan, Adam Roberts, Jennifer Welsh,

Dominik Zaum (eds.), The United Nations Security Council and War: The Evolution

of Thought and Practice since 1945, (Oxford University Press, 2008)

Sellers, Mortimer N. S., Republican Principles in International Law: The

Fundamental Requirements of a Just World Order, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2006)

Stacy, Helen M., Human Rights for the 21st Century, (Stanford University Press,

2009)

Sandholtz, Wayne, Kendall Stiles, International Norms and Cycles of Change,

(Oxford University Press, 2009)

Teson, Fernando R., Humanitarian Intervention: An Inquiry into Law and Morality,

(Transnational Publishers Inc., 1988)

Weiss, Thomas G., Military-Civilian Interactions: Humanitarian Crises and the

Responsibility to Protect, (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc., 2005)

Welsh, Jennifer M., ‘The Security Council and humanitarian Intervention’ in Lowe,

Vaughan, Adam Roberts, Jennifer Welsh, Dominik Zaum (eds.), The United Nations

Security Council and War: The Evolution of Thought and Practice since 1945,

(Oxford University Press, 2008)

Wilson, Richard Ashby (ed.), Human Rights in the ‘War on Terror’, (Cambridge

University Press, 2005)

23

Marion Russell

*

Case Concerning Military and Paramilitary Activities in and Against Nicaragua,

(Nicaragua v. United States of America) ICJ Reports, 1986

Charter of the United Nations, 1945

Corfu Channel Case (United Kingdom v. Albania) ICJ Reports, 1949

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 1976

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1976

Report of the Secretary-General, 54 GAOR, 4th plen. Mtg., 20 September 1999

United Nations Declaration on Friendly Relations; Nicaragua Case, ICJ Reports,

1986, p.14 at p.134 (para.268), 1970

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2625

Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and

Cooperation among States in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, (24

October 1970)

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2131

Declaration on the Inadmissibility of Intervention in the Domestic Affairs of States

and the Protection of Their Independence and Sovereignty, (21 December 1965)

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973

The Situation in Libya, (17 March 2011)

24