2710-12-2ads

advertisement

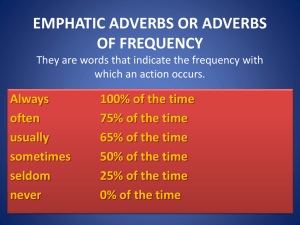

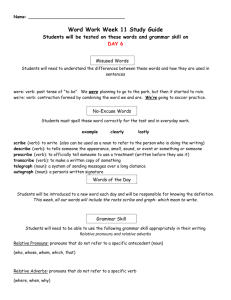

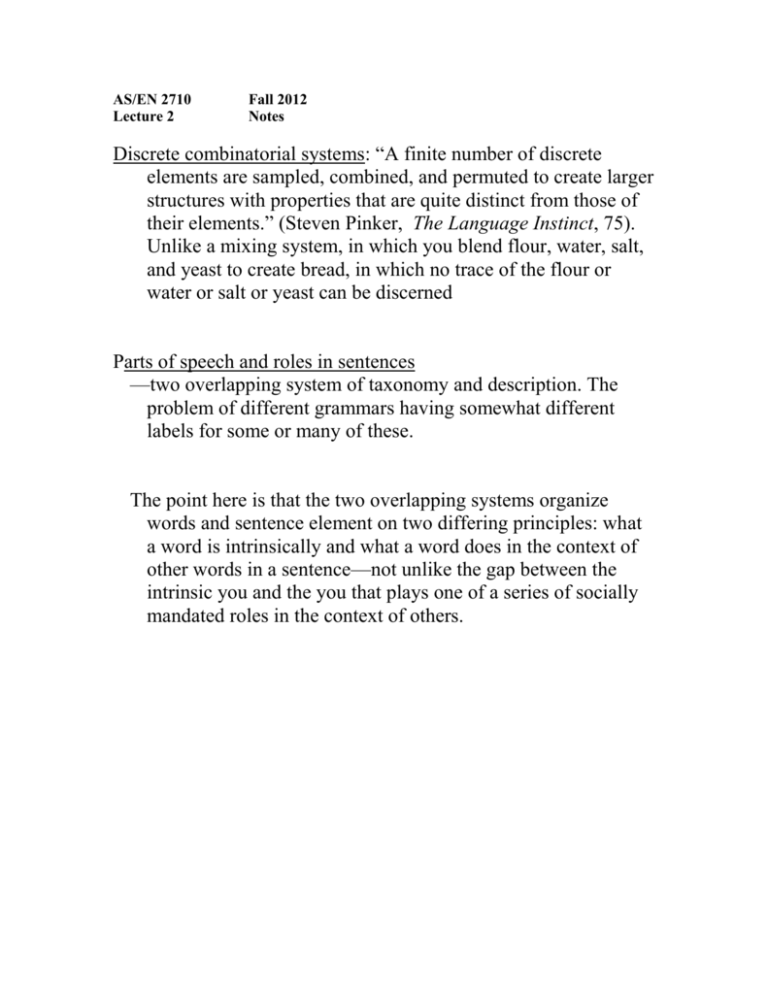

AS/EN 2710 Lecture 2 Fall 2012 Notes Discrete combinatorial systems: “A finite number of discrete elements are sampled, combined, and permuted to create larger structures with properties that are quite distinct from those of their elements.” (Steven Pinker, The Language Instinct, 75). Unlike a mixing system, in which you blend flour, water, salt, and yeast to create bread, in which no trace of the flour or water or salt or yeast can be discerned Parts of speech and roles in sentences —two overlapping system of taxonomy and description. The problem of different grammars having somewhat different labels for some or many of these. The point here is that the two overlapping systems organize words and sentence element on two differing principles: what a word is intrinsically and what a word does in the context of other words in a sentence—not unlike the gap between the intrinsic you and the you that plays one of a series of socially mandated roles in the context of others. Nomenclature: Several ways of naming Form classes versus structure classes; open and closed classes of words; content vs. architecture. Form/open/content classes: noun, verb, adjective, adverb Structure/closed/architecture classes: determiner, auxiliary, conjunction, preposition, qualifier, pronoun, numeral, interrogative, expletive, interjection “Morphological” definition (by form) vs. semantic definition (by referent) Morphologically, nouns are not words designating person place or thing. Rather, Nouns are words that can be made plural, whether by adding a terminal s or by some more recondite method and that can be made possessive by some combination of an s and an apostrophe. Grammatical/syntactic definition, which refers to the behaviours of nouns when they are in association with other words in sentences. Nouns most usually manifest themselves in sentences in groups of words called noun phrases, though contemporary grammarians ask us to expand our usual notion of phrases as consisting of more than one word, to include the possibility of one-word phrases. Verbs, which are traditionally said to be words representing an action or a state, are described morphologically as words that have tenses, in English, present and past tenses. &, in English all verbs except the verb “to be” have five forms—base form (1st person singular present); third person present singular (s form); simple past tense (ed form); past participle (en form); present participle (ing form). Adverbs and adjectives have conventionally been defined as words that modify verbs and nouns respectively—but, reasonably enough, structural grammarians noticed that these conventional works are only portions of these words’ job descriptions. Morphologically, adjectives and adverbs are that can be inflected—that is may be changes by adding suffixes—into comparative and superlative degrees the er and est forms for some words and the more most forms for others. In English, many adverbs are marked by what is called the derivational suffix “ly.” One can usually transform a word from one of the other form classes into an adverb by adding an “ly” (sometimes with adjustments “ily” “ally”) Modify—This may appear foolish but I think it’s worth pausing to thing a bit about the word usually used to describe what adjectives and adverbs do—they modify other words; they are modifiers—and to think about what it is that the word actually means—as in “Elvis and Zorro were sent to military school to get their attitudes modified.” As determiners fix and locate, so modifiers transform, most often in the direction of specificity, the words to which they are affixed Prepositional phrases, allow for the transformation of nouns for modification, or modifying purposes, that is, into what are functionally adjectives and adverbs, though K&F will call them, rightly, adjectivals and adverbials so as to designate their grammatical/syntactic role while not mistaking that fact that, in terms of form, the nouns in a prepositional phrase remain unreconstructedly nouns. And do recall that a noun following a preposition is the object of that preposition, which has no impact whatever on nouns, which have no inflected forms save the plural and the possessive, but, as we recall from last week, pronouns are inflected and do have accusation or objective forms and need to be found in those while dallying in preposition phrases. The basic structure of the sentence in English—a sentence being a group of words containing a subject and a predicate. In terms of forms, or parts of speech, about which we’ve been talking, the sentence is a union between a noun phrase or its surrogate and a verb phrase, Which is to say that while the subject may not always be a noun phrase, the predicate is always a verb phrase and a sentence has always a complete verb. Otherwise you’re in that place where the grader may scribble “fragment!!!!” in the margins. We in English have a kind of baseline of what Foster Wallace labels the s.v.o. (subject verb object) because, in simple sentences at least the subject precedes the predicate and, in the predicate, the object of the verb follows it 7) Kolln & Funk’s 10 Patterns Patterns 1-3 revolve around the use of the verb “to be.” Patterns 4 & 5 are predicated, literally, on “linking verbs” that is, verbs that require a subject complement (what might have been called in earlier books a “subjective completion,” a noun or an adjectival phrase to complete them and are not “to be.” Pattern 6 is an intransitive verb, requiring no object to complete its work (though clearly with many verbs intransitivity is a transitory state—it is a very small stretch to add “their weary heads” to K&F’s “The students’ rested.” The move from pattern 6 to 7 is an unwearying one. Patterns-7-10 are the transitive verb patterns. In each of these the verb requires an object, though in Patterns 8-10 that object has company The more canonical 10 types of sentences: 1) Arugula is on the phone. NP + be + ADV/TP 2) Arugula is tyrannical. NP + be + ADJ 3) Arugula is a tyrant. NP + be + NP1 4) Arugula seems homicidal. NP + VL + ADJ 5) Arugula became a monster. NP1 + VL + NP1 6) Arugula snored. NP + VI 7) Arugula signed the order. NP1 + VT + NP2 8) Arugula gave the rebels an ultimatum. NP1 + VT + NP2 + NP3 9) Arugula considered the envoy foolish. NP1 + VT + NP2 + ADJ 10) Arugula considered the envoy a fool. NP1 + VT + NP2 + NP2 USAGE MOMENT 2: I thought of enrolling in the Grammar course but, after going once, I found is was too disinterested. “In the following sentence the adjective ‘military’ modifies the noun ‘school.’” BUT “Elvis and Zorro were sent to military school to get their attitudes modified.” Griselda mordivit Quincam. Quincam mordivit Griselda. Mordivit Griselda Quincam. 7) 10 fundamental sentence Patterns Patterns 1-3 revolve around the use of the verb “to be.” Patterns 4 & 5 are predicated, literally, on “linking verbs” that is, verbs that require a subject complement (what might have been called in earlier books a “subjective completion,” a noun or an adjectival phrase to complete them and are not “to be.” Pattern 6 is an intransitive verb, requiring no object to complete its work (though clearly with many verbs intransitivity is a transitory state—it is a very small stretch to add “their weary heads” to K&F’s “The students’ rested.” The move from pattern 6 to 7 is an unwearying one. Patterns-7-10 are the transitive verb patterns. In each of these the verb requires an object, though in Patterns 8-10 that object has company