Stephen Davies

advertisement

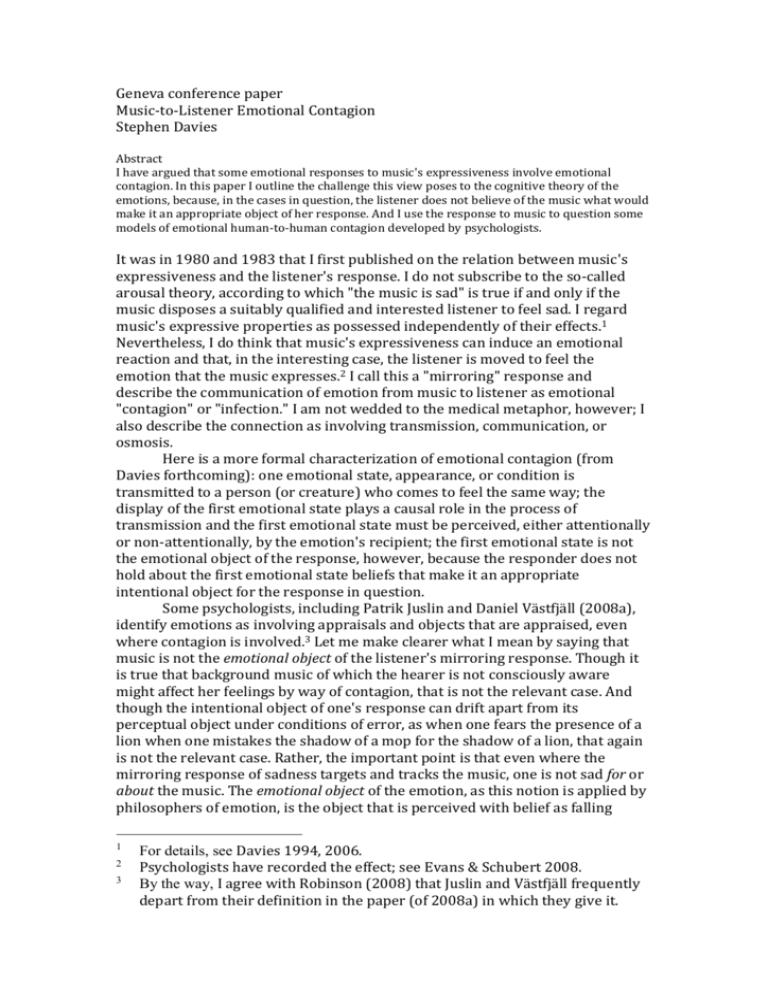

Geneva conference paper Music-to-Listener Emotional Contagion Stephen Davies Abstract I have argued that some emotional responses to music's expressiveness involve emotional contagion. In this paper I outline the challenge this view poses to the cognitive theory of the emotions, because, in the cases in question, the listener does not believe of the music what would make it an appropriate object of her response. And I use the response to music to question some models of emotional human-to-human contagion developed by psychologists. It was in 1980 and 1983 that I first published on the relation between music's expressiveness and the listener's response. I do not subscribe to the so-called arousal theory, according to which "the music is sad" is true if and only if the music disposes a suitably qualified and interested listener to feel sad. I regard music's expressive properties as possessed independently of their effects.1 Nevertheless, I do think that music's expressiveness can induce an emotional reaction and that, in the interesting case, the listener is moved to feel the emotion that the music expresses.2 I call this a "mirroring" response and describe the communication of emotion from music to listener as emotional "contagion" or "infection." I am not wedded to the medical metaphor, however; I also describe the connection as involving transmission, communication, or osmosis. Here is a more formal characterization of emotional contagion (from Davies forthcoming): one emotional state, appearance, or condition is transmitted to a person (or creature) who comes to feel the same way; the display of the first emotional state plays a causal role in the process of transmission and the first emotional state must be perceived, either attentionally or non-attentionally, by the emotion's recipient; the first emotional state is not the emotional object of the response, however, because the responder does not hold about the first emotional state beliefs that make it an appropriate intentional object for the response in question. Some psychologists, including Patrik Juslin and Daniel Västfjäll (2008a), identify emotions as involving appraisals and objects that are appraised, even where contagion is involved.3 Let me make clearer what I mean by saying that music is not the emotional object of the listener's mirroring response. Though it is true that background music of which the hearer is not consciously aware might affect her feelings by way of contagion, that is not the relevant case. And though the intentional object of one's response can drift apart from its perceptual object under conditions of error, as when one fears the presence of a lion when one mistakes the shadow of a mop for the shadow of a lion, that again is not the relevant case. Rather, the important point is that even where the mirroring response of sadness targets and tracks the music, one is not sad for or about the music. The emotional object of the emotion, as this notion is applied by philosophers of emotion, is the object that is perceived with belief as falling 1 2 3 For details, see Davies 1994, 2006. Psychologists have recorded the effect; see Evans & Schubert 2008. By the way, I agree with Robinson (2008) that Juslin and Västfjäll frequently depart from their definition in the paper (of 2008a) in which they give it. under the emotion-relevant description; for instance, where the emotion is envy of another, its emotional object is the person who I believe to possess something that I do not have and desire. While the listener's contagious response of sadness is reflected back to the sad music and in that sense takes the music as its object, the music is not the emotional object of the response because the listener does not believe of the music what would make it the emotional object of a sad response, namely, that the music is unfortunate, suffering, or regrettable. The music is not brought under the characterization that picks out the emotional object of sadness. And provided that nothing else is brought under that characterization, the response lacks an emotional object though the music remains its perceptual object. Emotional contagion should be distinguished from cases that are outwardly similar in that two people come to experience the same emotion (Davies forthcoming). The following are not instances of emotional contagion as I have characterized that notion: We both feel the same emotion because our emotions have a common intentional object about which we both hold the same emotion-relevant beliefs. (We both laugh at the same joke.) I react to your emotion by feeling the same, because I believe the basis of your reaction will also provide me with a reason to react similarly. (Seeing you flee in terror, I do the same without waiting to discover what you are terrified of.) Your emotion is the emotional object of my response and our emotions are the same. (You are angry that we are delayed, and I am angry that you are angry because you promised you would keep your cool.) I try to work out what you are feeling by imaginatively simulating your situation, or I use knowledge of your character and circumstances, and thereby empathically share your state. Also to be distinguished from emotional contagion are certain social influences on our reactions, for example, that people laugh more with others who laugh out loud, that they may feel a sense of community through shared emotion, or that they may become self-conscious and embarrassed to react as others do. I There are many mechanisms by which an emotional response to music might be induced. Juslin and Västfjäll (2008a) identify six of which emotional contagion is only one, the others being brain stem reflexes, evaluative conditioning, visual imagery, episodic memory, and musical expectancy. Some of these – for example, increased tension when a prediction about the course of the music is defeated or the reflex induction of a startle response by an unexpected loud chord – perhaps should not count as emotions, and others – for example, happiness when music triggers memories of a happy occasion – reveal more about the experiences of the listener than the nature of the music. One reason for focusing on the mirroring response, then, is that it is usually identified as a fully-fledged emotion that is directly connected to and is revealing of the music's expressive character. More important for the philosopher, perhaps, is that the mirroring response is intriguingly problematic in two respects. First, this type of response violates the cognitive theory of the emotions, which is a theory put forward by Anthony Kenny (1969) and Robert C. Solomon (1976) among others. Not everyone went so far as Solomon, who declares that emotions are no more than judgments, but the cognitive theory maintains that emotions are to be characterized in terms of the kinds of beliefs one holds about their objects. It cannot be fear for myself I feel unless I believe of something that it poses a threat to me; I cannot envy you unless I believe you possess something that I do not have and desire. The cognitive theory stresses the cognitive dimension of emotions, their intentionality or object-directedness, and the public aspect of the expressive behaviors that are in part constitutive of them, and contrasts with a physiological, often pneumatic, view that sees emotions as inner stirrings that are distinguished one from the other by their distinctive phenomenological profiles. Now, the mirroring response to music does not align with the cognitive theory because, as I observed earlier, the listener does not believe of sad music what would make it an appropriate emotional object of the sad response she experiences, namely, that there is something about the music that is unfortunate or regrettable. She does not believe the music is sentient, and hence does not believe that it suffers the sadness it expresses, so there is nothing here for her to get sad about, yet she does become sad. Not all her sad responses are of this kind; she might be saddened by the music's banality and execrable execution. Such responses match the cognitive theory and are otherwise unproblematic.4 But the mirroring response of sadness does not rely on her beliefs about the music, and where she thinks the music is good – is indeed better for its expressiveness – such beliefs as she has are at odds with the sad response she feels. The second respect in which the mirroring response is problematic is this: it appears to be non-rational, yet notwithstanding this we often would acknowledge such a response as evidence that the listener follows the music with understanding. Typically, we justify our emotions by showing that their emotional objects have the emotion-relevant qualities that we believe them to have. I justify my fear for myself by pointing to the dangerous qualities of the apparently hungry lion that shares the room with me, for instance. But in the case of the mirroring response, the listener does not hold beliefs about the music appropriate for her response to its expressiveness. She cannot justify her response of sadness in the usual way, by indicating what is unfortunate and regrettable about the music or its expressiveness.5 II There are several ways one might try to address the first worry. One possibility is that the emotion takes something other than the music as its emotional object. Perhaps the listener believes the composer must have experienced loss and suffering to compose such sad music, and her sadness is directed to him. It seems implausible to suggest that all mirroring responses could be explained away in this fashion, however; after all, composers often were happy to be commissioned 4 5 Peter Kivy (1987) is one philosopher who argues that all emotional responses to music are of this kind and that the mirroring response never occurs. There is a third issue, specifically about the sad (rather than the happy) mirroring response, that I will not consider here, namely, why we enjoy and return to music that makes us feel sad. For discussion, see Davies 1994. to write sad requiems. A second, more promising approach is to argue that make-believe can substitute for belief in securing an emotion to its object. And it is quite plausible to suggest that our responses to fictional novels, dramas, paintings, and movies involve making believe that one is seeing (or hearing about) actual events, and that this grounds the response, whether we call it a genuine emotion or not.6 Moreover, such a move answers the second concern as well as the first; we can justify the rationality of the response by reference to what is true in the fiction, that is, to the truths that the audience make-believedly entertains under the artist's direction (Davies 1983). But what is one supposed to make-believe on hearing an "abstract" musical work without a sung text, program story, or literary title? Several philosophers have suggested that the listener make-believes that the music provides a narrative about the experiences of a hypothetical persona.7 The listener feels sad because she hears the music as a direct expression of that fictional persona's suffering, just as she feels sad on reading Anna Karenina or weeps at the end of La Bohème though she knows that Anna and Mimi are no more real than is the persona imagined as being in the music. I agree that the cognitive theory should be modified to include makebelieve as well as belief (and perhaps other modes of mental representation as well) and that this allows us to make sense of our responses to fictional narratives and depictions. Moreover, I allow that the hypothetical persona account does capture an important aspect of our experience of music's expressiveness, namely, that it is more like a direct encounter with someone who feels an emotion and shows it than it is like being told about or reading a description of such matters. Nevertheless, I am not convinced that the hypothetical persona theory correctly characterizes music's expressiveness and our mode of reacting to this.8 In brief, many listeners who recognize music's expressiveness are not aware of the acts of make-believe posited by the theory, and what might be imagined along such lines is too little controlled by the course of the music to explain agreement about what music expresses. III My response to the first issue did not take the form of a defense of or friendly amendment to the cognitive theory of the emotions. A number of problem cases for that theory are widely recognized: phobias (which do not involve beliefs appropriate to the emotion experienced) and moods (which are apparently not targeted on any specific intentional objects and therefore do not involve emotion-relevant object-directed beliefs). The musical case does not fit in either of these camps, but is a new kind of counterexample that was not widely recognized as such. This does not mean that the musical case is one peculiar to the aesthetic context, however, which is a good thing because the application of emotion terms under circumstances that bear no resemblance to the wider context of their use, as in talk of sui generis artistic emotions or responses, is 6 7 8 Carroll (1990, 1997) and Lamarque (1981) count these as genuine emotions, Walton (1990) does not. For example, see Levinson 1996, 2006; Robinson 2005. For details, see Davies 1983, 1997, 2006. rightly regarded with suspicion by contemporary philosophers of art. In fact, appealing to what I took to be commonplaces of folk psychology, I claimed that emotional contagion is familiar as a response to our fellow humans. We often catch or are affected by the mood of others. Moreover, the outcome is not necessarily diminished when we move to modes of expression that do not involve sentience. I speculate that a person would be more likely to be depressed working on the production of masks of tragedy than on the production of masks of comedy. And to move yet further from the human case, it is widely held that the weather and colors can affect our emotions, and we predicate expressive properties to both the weather and to colors. So my response to the first concern, that the musical mirroring response is not consistent with the cognitive theory of the emotions (even if amended to include make-believe alongside belief) can be summarized this way: yes, the musical reaction is an exception to the cognitive theory of the emotions, but there are other exceptions to the theory, including ones that parallel the musical case. As for the second problem – that the listener does not have the beliefs that could justify her response – one should admit that it has some force. It is not obvious that we should criticize someone who is not moved to sadness by sad music, because it is not as if he thereby betrays callousness or lack of sympathy. But we can also argue that, if the mirroring response does occur, it can be justified, not by reference to emotion-relevant beliefs but rather in the sense that no other equally non-cognitively directed response is equally apt. By comparison with the person who is typically cheered by sad music and depressed by happy music, but without believing or make-believing about it anything that makes it a fit object for happiness or depression, the person who is cheered by happy music or saddened by gloomy music seems normal and has the appropriate response. Or to make the point differently, there seems to be a place prepared in our natural history for the mirroring response in a way that is not true for alternatives that are similar in also not being cognitively directed. It is for this reason that the listener's response can be taken as indexing her sensitive comprehension of the music's character. We might draw a parallel here with emotional responses to what are known to be fictions. Some philosophers regard these as paradoxical and irrational. After all, why should I fear the movie monster that I know not to exist and, hence, not to be able to harm me? Whatever one says in answer to this paradox, it seems reasonable to suggest that it is more rational to fear the monster than the cowering, little old lady that it is threatening in the film. In the same way, it is more rational to be saddened by sad music and gladdened by happy music, even if I think the music expresses no one's feelings in either case and even if I hold no other emotion-relevant beliefs about the music, than it is to feel the reverse. IV At the time I was developing these views, psychologists apparently had not clearly isolated and studied the phenomenon of emotional contagion, though there had been much work on empathy and sympathy. The pioneering Emotional Contagion of Elaine Hatfield, John Cacioppo, and Richard Rapson came in 1994. Of course, those earlier researchers are not interested in the musical case; they study the human-to-human transmission of affect. And their primary interest, unlike mine, is in the mechanism causally responsible for inducing in one person what is felt by the other. In brief, they describe this mechanism as follows: (i) in attending to person A, her interlocutor, person B tends unconsciously to ape A's facial expressions, vocal tone, etc.; (ii) as part of working out what she feels, B monitors her facial expression, vocal tone, etc.; (iii) so, if A feels some emotion and betrays it in her appearance, tone, and action, B is inclined to come to feel the same emotion. In a different work, Teresa Brennan (2004) surmises that the mechanism involves the subconscious detection of pheromones. However, if there is emotional contagion between music and humans, or between colors or the weather and humans, it cannot be facial mimicry or pheromones that underpin it because music, colors, and the weather do not present a human physiognomy or give off pheromones. The error of these psychologists is to equate the phenomenon with causal mechanisms that apply only in the cases of contagion that interest them. We need a more careful characterization of the phenomenon, such as I offered earlier. When psychologists searched for an analogous role for music in the induction of emotion, it was in the context of testing how background music affects the mood and behavior of diners and shoppers and in the use of music as therapy.9 Neither kind of study specifically targets music-to-listener emotional contagion, as opposed to more general interactive effects between music and mood, and in many cases the concern is with effects that do not involve the hearer's attention to the music as such. As a result, these studies do not provide useful paradigms for the study of emotional contagion where this results from the listener's close attention to the music's expressive character in a context of trying to follow the music with understanding. Psychologists concerned with music-to-listener emotional contagion of the attentional variety tend to return to the human-to-human model. Emotional contagion "refers to a process whereby an emotion is induced by a piece of music because the listener perceives the emotional expression of the music, and then 'mimics' this expression internally, which by means of either peripheral feedback from muscles, or a more direct activation of the relevant emotional representations in the brain, leads to an induction of the same emotion … Recent research has suggested that the process of emotional contagion may occur through the mediation of so-called mirror neurons discovered in studies of the monkey premotor cortex in the 1990s" (Juslin & Västfjäll 2008a, 565). The problem with this is that it appears to turn what is supposed to be literal for human-to-human contagion into something metaphorical. It is not as if the music has muscles the movements of which can be mimicked, or a premotor cortex with neuronal activity that can be mirrored in the brains of listeners. Because of their apparently metaphorical character, the explanatory power of such characterizations of the relevant mechanisms is questionable. 9 On shopping, see Bruner 1990; North & Milliman 1982, 1986; Hargreaves 1997; on therapy, see Bunt & Pavlicevic 2001. Yet talk of emotional contagion seems perfectly apt in such cases. In part this is because talk of musical movement, pattern, tension, and expressive appearances is literal, or so I would maintain. Such attributions are secondary, in that the meanings of the relevant terms are not first taught by reference to such examples, but once the secondary extensions of these meanings are acquired, the terms have the kind of shared interpersonal use that live metaphors lack (Davies 1994). If this is so, talk of listeners mimicking the music is not merely poetic; even if there are no musical muscles or neuronal patterns to be imitated or mirrored, there can be musical movement and process, patterns of tension and release, and the like. How then does emotional contagion operate in the musical case? That is for scientists to discover, but it is possible to offer some speculative suggestions. I favor the view that music is expressive because we experience it as presenting the kind of carriage, gait, or demeanor that can be symptomatic of states such as happiness, sadness, anger, sassy sexuality, and so on.10 If contagion operates through mimicry, we might expect the listener to adopt bodily postures and attitudes (or posturally relevant muscular proprioceptions) like those apparent in the music's progress.11 Vocal mimicry, in the form of subtle tensing or flexing of vocal muscles, would also be a predictable response to vocal music or to acts of subvocal singing along with instrumental music.12 And where the flux of music is felt as an articulated pattern of tensing and relaxing, this is likely to be imaged and mimed within the body, perhaps in ways that are neither subpostural nor subvocal. Finally, there is the possibility that music works on the brain, not only by eliciting physical-cum-physiological changes that nudge the subject as she becomes aware of them toward affective appraisals and responses, but also more immediately, by directly stimulating cortical regions linked with emotional recognitions and responses. Many and diverse routes of emotional transmission might be involved, perhaps simultaneously. Stephen Davies Department of Philosophy, University of Auckland. 10 11 12 For details see Davies 1980, 1994, 2006. For relevant empirical data, see Janata & Grafton 2003. For relevant empirical data, see Koelsch, Fritz, Crammon, Müller, & Frederici 2006. Juslin & Laukka (2003) and Juslin & Västfjäll (2008a), who postulate that the response to music can be explained as involving emotional contagion, make the comparison not with facial mimicry but with the communication of affect through vocal cues. See Patel 2008 on how this hypothesis might be tested via brain imaging; Simpson, Oliver, & Fragaszy 2008 suggest brain-imaging results count against the thesis. (Juslin & Västfjäll reject this criticism in 2008b.) Simpson, Oliver, & Fragaszy suggest their results – that instrumental music is not processed by parts of the brain concerned with the voice – show that contagion is not a mechanism for the arousal of emotion by music, but that conclusion is unwarranted because they do not consider alternatives to the suggestion by Juslin and his fellow researchers that music is experiences as a super-expressive voice. References Brennan, Teresa. 2004. The Transmission of Affect, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press). Bruner, G. C. 1990. "Music, Mood, and Marketing," Journal of Marketing, 54 (4), 94-104. Bunt, Leslie & Pavlicevic, Mercédès. 2001. "Music and Emotion: Perspectives from Music Therapy," in P. N. Juslin & J. A. Sloboda (eds), Music and Emotion: Theory and Research, (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 181201 Carroll, Noël. 1990. The Philosophy of Horror or Paradoxes of the Heart, (New York: Routledge). — 1997. "Art, Narrative, and Emotion," in M. Hjort & S. Laver (eds.) Emotion and the Arts, (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 190-211. Davies, Stephen. 1980. "The Expression of Emotion in Music," Mind, 89, 67-86. — 1983. "The Rationality of Aesthetic Responses," British Journal of Aesthetics, 23, 38-47. — 1994. Musical Meaning and Expression, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press). — 1997. "Contra the Hypothetical Persona in Music," in M. Hjort & S. Laver (eds.) Emotion and the Arts, (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 95-109. — 2006. "Artistic Expression and the Hard Case of Pure Music," in M. Kieran (ed.), Contemporary Debates in Aesthetics and the Philosophy of Art, (Oxford: Blackwell), 179-191. — forthcoming. "Infectious Music: Music-Listener Emotional Contagion," in Peter Goldie & Amy Coplan (eds.) Empathy: Philosophical and Psychological Perspectives, (Oxford: Oxford University Press). Evans, P. & Schubert, E. 2008. "Relationships between express and felt emotions in music," Musicae Scientiae, 12, 75 – 99. Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Rapson, R. L. 1994. Emotional Contagion, (New York: Cambridge University Press). Janata, P. & Grafton, S. T. 2003. "Swinging in the Brain: Shared Neural Substrates for Behaviors Related to Sequencing and Music," Nature Neuroscience, 6, 682-7. Juslin, Patrik N. & Laukka, Petri. 2003. "Communication of emotion in vocal expression and music performance: Different channels, same code?" Psychological Bulletin, 129/5, 770-814. Juslin, Patrik N. & Västfjäll, Daniel. 2008a. "Emotional responses to music: The need to consider underlying mechanisms," Behavioural and Brain Sciences, 31, 559-75. Juslin, Patrik N. & Västfjäll, Daniel. 2008b. "All emotions are not created equal: Reaching beyond the traditional disputes," Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 31, 600-12. Kenny, Anthony. 1963. Action, Emotion, and Will, (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul). Kivy, Peter. 1987. "How Music Moves," in P. Alperson (ed.), What Is Music?: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Music, (New York: Haven), 149-163. Koelsch, S., Fritz, T., Crammon, D. Y. von, Müller, K., & Frederici, A. D. 2006. "Investigating Emotion with Music: an fMRI Study," Human Brain Mapping, 27(3): 239-50. Lamarque, Peter. 1981. "How Can We Fear and Pity Fictions?" British Journal of Aesthetics, 21, 291-304. Levinson, Jerrold. 1996. "Musical Expressiveness," in The Pleasures of Aesthetics, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press), 90-125. — 2006. "Musical Expressiveness as Hearability-as-expression," in M. Kieran (ed.), Contemporary Debates in Aesthetics and the Philosophy of Art, (Oxford: Blackwell), 192-204. Milliman, R. E. 1982. "Using Background Music to Affect the Behavior of Supermarket Shoppers," Journal of Marketing, 46 (3), 86-91. — 1986. "The Influence of Background Music on the Behavior of Restaurant Patrons," Journal of Consumer Research, 13 (2), 286-9. North, A. C., & Hargreaves, D. J. 1997. "Music and Consumer Behaviour," in D. J. Hargreaves and A. C. North (eds.), The Social Psychology of Music, (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 268-89. Patel, Aniruddh D. 2008. "A neurobiological strategy for exploring links between emotion recognition in music and speech," Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 31, 589-90. Robinson, Jenefer. 2005. Deeper than Reason: Emotion and Its Role in Literature, Music, and Art, (Oxford: Clarendon Press). Robinson, Jenefer. 2008. "Do all musical emotions have the music itself as their intentional object?" Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 31, 592-3. Simpson, Elisabeth A., Oliver, William T., & Fragaszy, Dorothy. 2008. "Superexpressive Voices: Music to my Ears?" Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 31, 596-7. Solomon, Robert C. 1976. The Passions, (Garden City: Anchor). Walton, Kendall L. 1990. Mimesis as Make-Believe: On the Foundations of the Representational Arts, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).