CVA Perspectives

advertisement

Perspectives: An Overview of Comparative Considerations

of Cerebrovascular Accidents

PETER L. ROME

╪

ABSTRACT: This paper seeks to contrast reports concerning major adverse side effects, viz. cerebrovascular

accidents (CVAs) attributed to cervical spine manipulation, within a broad perspective of medical procedures.

It also seeks to correlate the incidence rates of other adverse events and medical procedures with the general

incidence rate of CVAs. On analysis, an accurate position would indicate that cervical spinal manipulation is

one of the more conservative, least invasive and safest of procedures in the provision of human health care

services. The paper also alludes to the political connotations on the subject.

INDEX TERMS: MeSH: ARTERIES; CEREBROVASCULAR DISORDERS; CERVICAL VERTEBRAE; CHIROPRACTIC;

MANIPULATION, ORTHOPEDIC; IATROGENIC DISEASE; ORTHOPEDICS; OSTEOPATHIC MEDICINE; PERSUASIVE

COMMUNICATION; PHYSICAL THERAPY; SPINE; VERTEBROBASILAR ACCIDENTS.

╪

Peter L. Rome, D.C.

Private practice of chiropractic Mount Waverley, Victoria

Received 26 March 1999, accepted 14 May 1999.

Chiropr J Aust 1999; 29 (3): 87—102

INTRODUCTION

There can be a risk involved with virtually all medical procedures, from the taking of blood samples, 1 use of

vitamins 2 and "natural" medications, 3 to vaccinations, 4 drugs 2 and surgery. 5 At times, these risks seem to

be either disregarded or categorised as an acceptable adverse side effect — the risk/benefit ratio. For instance,

the Australian College of Ophthalmologists has issued a policy relating to laser surgery to correct myopia “...

with low and acceptable rates of complications.” 6 A further study on endarterectomies stated that, “On

average, the immediate risk of surgery was worth trading off against the long-term risk of stroke without

surgery (but only) when the stenosis was greater than about 80% diameter...” 7 Currently, there is a greater

move towards “informed consent” so that such risk factors are understood by patients.

White defines apoplexy as brain damage where there is “... an acute neurological deficit resulting in death, or

lasting more than 24 hours and classified by a physician as a stroke.” 8

In his literature search, Terrett found that historically, the first adverse accident related to bone-setting was

recorded in 1871 — almost a quarter century before chiropractic was founded in 1895. The first vascular

accident following manipulation was reported in 1934 — almost 40 years after our profession was founded. 9

It has been estimated that the incidence of apoplexy in Australia is likely to rise by 70% in the next twenty

years, due to the ageing of the population.10 The relative prevalence of such incidents is further exemplified

by the indication that “everyone had some degree of stroke risk.” 10 This statement is reflected later in this

paper, citing Myler, who calculated that the rate of fatal cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs) in the general

population is greater than that of manipulated patients.11

Concern at the serious nature of CVAs should also be tempered by the knowledge that a significant proportion

of those who experience an adverse reaction to spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) undergo complete or

partial recovery,12 similar to those who experience vertebral artery dissection (VAD) due to other causes. 13-15

This paper also compares the mortality rates of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) and other medical

procedures with SMT. The relative incidence rates show SMT to be considerably more favourable than

NSAIDs from a safety viewpoint. 16

To castigate or reject spinal manipulative therapy as inappropriate or comparatively dangerous is not only

unwarranted, but conveniently overlooks the morbidity and mortality rates of other interventions. Such

concern would seem out of proportion to that involved with everyday articular release of an intervertebral

facet fixation — a vertebral manipulation.

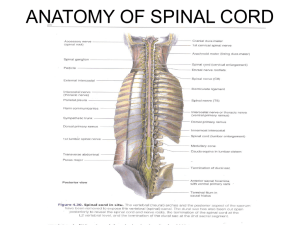

Concern over, and considerations of, spinal manipulation does, however, also serve to emphasise the potential

for positive integrated influences associated with important neurological and vascular elements within the

dysfunction of dynamic vertebral segments — the vertebral subluxation complex.

METHOD

This paper was compiled from a number of sources as ongoing research over some years. These sources

included reference lists, Index Medicus, manual searches and computer searches as well as news items. The

network of citations obtained led to further searches. As this paper was being prepared for submission,

relevant papers continued to appear in the literature. It was necessary 10 “draw the line,” so these further

references had to be omitted.

Information thus gleaned was collated and reviewed in an attempt to assess a comparative risk of CVAs

attributed to SMT. A contrast of morbidity and mortality rates of other medical procedures and health

conditions has been considered as a means of illustrating the risk factor of various therapeutic procedures and

interventions.

To gain a more accurate perspective of the claimed adverse events attributed to chiropractic, a comparison has

been made of the apparent high rate of adverse events of some medical procedures with the apparent low rate

of adverse events involving spinal manipulation.

As a further perspective, the incidence rates of CVAs associated with everyday events are also noted.

Table 1

INCIDENCE RATES OF CEREBROVASCULAR ACCIDENTS

ASSOCIATED WITH SPINAL MANIPULATIVE THERAPY

YEAR

1963

1968

1972

1980

1981

1983

1985

1991

1992

1993

1993

1994

AUTHORS

Cyriax 17

Livingstone 18

Maigne 19

Jaskoviak 20

Hosek et al. 12

Gutman 12,21

Dvorak & Orelli 12,21

Patjin 16

Shekelle 22

Carey 23

Haldeman 16

Haynes 24

1995

1996

Carlini 16

Lauretti 25

1996

Lauretti 26

INCIDENCE

1: 1 0,000,000

“Few” in “possibly 75,000,000” p.a.

1 :” "Several tens of millions”

(over 15 yr) 0:5,000,000

1:1,000,000

1 :400,000

2-3:1,000,000

1 :518,000

1:100,000,000 (cauda equina/lumbar manipulations)

1:3,846,153

1-2: 1,000,000

1:100,000 (N.B.: This statistic applies to the ratio per patient, not per

visit)

1 :500,000

1 :2,000,000 (National Chiropractic Mutual Insurance

Company per cervical manipulation)

1:1,000,000

(1 neurological complication per 1 million patient

visits)

* Manipulation-related mortality rate averaged for all professions is 1 in 2 years, 34 over 61 years, worldwide.

21

** Spinal Mobilization: In 1993, the physiotherapist Michaeli reported a “...similarity in the nature and

prevalence of complications following cervical mobilisation and manipulation...” In some instances the

reported incidence rate of adverse effects was higher for mobilisation than manipulation. 27

LIMITATIONS OF THIS REVIEW

A review such as this is limited in the consideration of such factors as the patient's age and underlying health

status, frequency of the procedure involved, necessity for a particular procedure, and available options to a

particular procedure against the benefit/outcome.

Consideration has been given to the following:

Some of the references are not recent, however it has been noticed that morbidity and mortality rates in

many medical procedures have altered little in 20-30 years.

While it is difficult to draw direct comparisons on a topic such as this, the inference from published

medical papers is that SMT has a high incidence rate — presumably compared to medical care and

procedures. In researching this topic it appeared that there were more papers published on the side

effects of medical procedures than on the prevention of such side effects.

While it may be argued that medicine is involved with more serious conditions, this paper is an attempt

to portray certain perspectives only. It is relevant to compare one procedure with another to be able to

rate its risk in perspective — to know where it stands in the overall picture.

Consideration was also given to various forms of CVA and the sites of CVA lesions. Rather than

differentiate these, it was decided to conduct a general overview at this stage.

It could be argued that in relation to SMT, incidence figures relate only to published reports, however the

same can also be said for the incidence rates involving all professions, as not all adverse side effects are

necessarily recorded in the literature.

REVIEW

The incidence rate of serious neurological compromise associated with manipulation is remarkably low in

itself. Estimates range from as low as 1:10 million 17 (see Table 1). The incidence rate gains an even lower

perspective when comparisons are made with other medical procedures, and when considered in light of

incidents associated with some everyday circumstances (see other tables). In relation to SMT, it is rare that a

serious side effect occurs. 16,28,29 A significant proportion of these appear to be of minor severity and

transient in nature. 28,30

Michaeli also states that “The vast majority of these 'accidents' (CVAs) are of a transient nature and therefore

may not have been worthy of mention in the literature.” 31

Assendelft et al. found that of the 165 patients with associated side effects of spinal manipulation, 44 (26.7%)

made a complete recovery following the initial onset and that “serious complications (are) generally

considered to be low.” This study included both cervical and lumbar complications. Some 49% of the lumbar

complications occurred during manipulation under anaesthesia (MUA). MUA is not a customary chiropractic

procedure. 28

On the positive side, clinical observations of the beneficial influence of spinal manipulation on neurological

function have already been noted. Carrick reported that certain procedures, including manipulative

techniques, can provide remarkably promising responses in assisting some patients in degrees of recovery

from central nervous system (CNS) lesions, including some forms of stroke, coma, and movement disorders

such as Parkinson's disease and Friedrich's ataxia. 32

Perspectives on CVAs

SMT Patients vs. General Population

Rather than being contraindicated in CNS conditions, Carrick's work would suggest that the association of

cervical spine adjustments upon the brain and spinal cord would, in fact appear to be a non-invasive, nondrug, potent health procedure by which to positively influence neural physiology. 33

Myler calculated that, given the statistical facts, it is less likely for a chiropractic patient to experience a fatal

vertebral artery injury than it is for a person within the general population to experience a fatal stroke. He

compared the rate of CVAs in the general population with that of chiropractic patients in the U.S. 11 “Stroke is

the third leading cause of death in the United States.” 34

Although there are no recorded deaths from chiropractic SMT in Australia, Myler has calculated the rate of

fatal vertebral artery injury after cervical manipulation in the U.S. at 0.00025% (1 :400,000), while the rate

of deaths from CVA in the general population was 0.00057% (1 : 176,900) — more than double the rate of

manipulated patients. 11 While there may well be other factors, such as age, type of apoplexy and healthier

patients attending chiropractors, his findings are still an indication of the extremely low rate of CVA incidents

in chiropractic practices.

Myler's stated rate of 1:400,000 fatal SMT-related CVAs would seem conservative. In Australia, if 3,000

chiropractors administered just 100 cervical spinal adjustments each week for 50 weeks, the procedure would

have been carried out 15,000,000 times a year, making a total of 75,000,000 cervical manipulative

procedures in five years, with no recorded deaths due to chiropractic manipulation. These figures are more in

line with Carey's Canadian study in 1993, which found no fatalities in 50 million chiropractic manipulations.

23 (see also Table 1).

SMT Patients vs. Patients Prescribed NSAIDs

In their paper comparing CVA risk between SMT and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAlDs), Dabbs

and Lauretti found that NSAlDs have a risk factor four hundred times greater than spinal manipulative

therapy. They found that the rate of death from gastrointestinal bleeding caused by NSAIDS (including

bleeding from abdominal ulcers) was 0.04% — 160 times greater than neck manipulation at 0.00025% (i.e.,

1:2,500 vs. 1:400,000). By comparison, the risk of a non-fatal arterial injury from manipulation was

calculated as 0.001 % (1:100,000), and from NSAIDS, 0.4% (1 :250) — also a difference of 400 times. 16

In Australia in 1992, it was stated that there were some 200 deaths alone from the use of NSAIDs. 35 Six years

later, a more recent estimate stated, “there would be hundreds of deaths a year from side-effects of the drugs

(NSAlDs ).” 36

General Incidence of Apoplexy and TIAs

Each year some 37,000 Australians suffer a stroke — that is more than 100 every day (1:514 = 0.195%). Of

these patients, 12,000 die (1:1,583 = .063%), while another 12,000 are permanently disabled. 37 Another study

revealed a mortality rate of 70 per 100,000 population (1:1,429 or 13,300 p.a.). 38 Some 20% of stroke

patients (7,400) have diabetes, which can be a predisposing factor. 36

Each day, some 25 Australians experience a transient ischaemic attack (TIA). 39 Based on a population of 19

million, this is a daily rate of one in 760,000 people (.00013%), and an annual rate of 9,125 patients or

1:2,082 (0.05%) (see Table 2).

Hart stated that in the U.S., "between 0.5 and 2.5 cases per year (of vertebral artery dissection [VAD]) are

reported from large referral-based hospitals." 40 In pointing out that dissection may occur at any point in the

course of the vertebral artery, he notes three categories: spontaneous, traumatic and "minor, non-penetrating

trauma/neck torsion positioned somewhere in between." This infers that any SMT-related VAD could only be

a portion of the 0.5-2.5 cases reported by these hospitals annually. Hart also noted that the course of the

condition of most patients stabilises within one to two weeks.

Insidious and Spontaneous Apoplexy

In cases of CVA, pre-existing risk factors such as inherent arterial weakness, are not always identifiable,

hence the designation, "spontaneous CVA." 9,13,40-46 The cost and risk of conclusive screening for such

conditions would seem prohibitive if not impracticable, and conducting such investigations may involve

further risk. The insidious nature of these unrecognisable conditions poses a significant underlying risk if they

are present, however incidents seem to be extremely rare 16,18,29 (see Table 1).

Table 2

INCIDENCE OF CEREBROVASCULAR ACCIDENTS

MORBIDITY

RATIO

General population

MORTALITY

%

11*

General population 36*

1:514

0.195

General population 37*

NSAIDs

1:250

16

0.4

TIAs (daily) 38

TIAs (annually) 38

Chiropractic/SMT

11,16

Chiropractic/SMT 23

RATIO

%

1:176,900

0.00057

1:1,583

0.063

1:1 ,426

0.07

1:2,500

0.04

1:760,000

0.00013

1 :2,082

0.05

1:100,000

0.001

1:400,000

.00025

1:3,840,153

0.000035

Nil:50,000,000

———

Estimated in this paper

Nil:75,000,000

* The 1000+ fold discrepancy in these figures cannot be explained.

The more insidious predisposing factors in CVAs include such conditions as asymptomatic congenital arterial

weakness, 47 obscure weakness due to previous trauma, 41,42,47 unforeseen congenital arterial anomalies,

14,48-51 and anomalous cervical muscle structure. 51-54

Due to the prevalence of previous trauma in daily life, especially motor vehicle accidents, one could expect

resultant arterial weaknesses to be a common predisposing aetiological factor in spontaneous apoplexy or in

incidents of apparent iatrogenesis.

At other times, identifiable conditions include recognisable signs, symptoms, anatomical anomalies,

pathological and pathophysiological states. 49,55,56 These are important considerations in a therapeutic field

of neurorgic influence.

The more obvious indications of risk factors can include smoking, oral contraceptives, migraines,

hypertension, arteriosclerosis, diabetes mellitus, fibromuscular dysplasia, 11,12,37 as well as colitis, 57-59 to

name a few. Terrett and Sturzenegger both state that sudden and severe onset of headache and neck pain can

be more immediate key symptomatic indicators. 55,60

Commenting on an unusual fatality where a player was struck by a cricket ball, an Australian coroner was

reported in a 1987 newspaper article as stating that, "... it was possible that a congenital weak spot in an artery

at the base of the brain had ruptured when (the patient) jerked his head. Dr Drake said everyone had such

weak spots, but they might never rupture." 47 Such an observation would suggest that some VBAs may be

coincidental.

It is further reported that other seemingly innocent activities have produced similar CVAs in rather innocuous

circumstances (Table 3). These particularly include neck extension during various normal everyday

procedures. 72,95 An interesting example of this has been reported by Goldrey as a form of "Sightseers CVA".

75 This seems somewhat similar to the anecdotal "Golden Gate Bridge Sightseers Stroke." Such examples

highlight Fogelhom and Carli's point that at times, frequent rotation and extension of the head is suspected of

aggravating a weakened vertebral artery in vulnerable patients, with the onset of CVA being virtually

impossible to predict. 61

Professions Associated with SMT

In 1992, Shekelle estimated that in the U.S., 94% of spinal manipulation was carried out by chiropractors, 4%

by osteopaths and 2% by medical practitioners. 22 Recently De Fabio claimed that physiotherapists also

conduct 2% of SMT in the U.S. 101

Calculations based on Terrett's 1995 study covering 58 years, however, showed that only 64.1 % of

78 manipulation-related "catastrophes "were attributed to chiropractors, while 8.97% were

attributed to medical practitioners, who conduct only 2% of the manipulative procedures, and

10.26% to osteopaths, who conduct only 4% of manipulative procedures in the U.S. The balance

of some 17% comprised a miscellaneous grouping. Terrett questions the reliability and accuracy of ascribing

and impugning chiropractors by incorrectly attributed involvement in "all" adverse effects through the

medical literature. 54

Winterstein also noted that the proportion of chiropractor-related incidents is far less than 94% of spinal

manipulation carried out by this one profession. 102

Further extrapolation of these available figures would suggest that while conducting only 1/47

of manipulative procedures, medicine has 20.89 times, and osteopathy (2/47) has 3.92 times

greater mortality rates in spinal manipulation than chiropractic.

In his 1998 study, Terrett found that in over 61 years, the practitioners reported as being associated with

major manipulative side effects in 219 examined cases were actually practitioners from quite diverse

backgrounds, education and training, not just from a chiropractic background, as mostly reported. The list

also includes physiotherapists, osteopaths, naturopaths, a barber, masseurs, and medical practitioners (see

Table 4). These major side effects comprised a total of 34 deaths worldwide over the 61 years (1: 1.8 yr). In

addition, of the 185 other, more serious side effects, 44 (23.8%) either subsided or almost completely resolved

with minor neurological deficits. 54

As a comparison to the 34 deaths associated with manipulation over 61 years worldwide, Burgess reported in

1998 that there were nine reported deaths in thirteen months due to pertussis in Australia in 1997. 4 The

pertussis deaths did not receive anything like the publicity the manipulative incidents seem to. At the

monthly rate (1.44 per million), there would be 1,054.08 pertussis deaths over the same 61 year time span-a

rate 3,100% higher.

By comparison, there have been three SMT-associated fatalities ever recorded in Australia —

all involving medical practitioners. 112

Cyriax, the doyen of medical spinal manipulation, stated that in relation to major side effects associated with

manipulation of the cervical spine, "the risk works out at about one in ten million manipulations, and provides

no argument against an attempt at manipulative reduction in suitable cases." He then goes on to discuss "The

danger of not manipulating." 17

Livingstone, in commenting on the "25,000 manipulators" in the U.S. in 1968, stated that there were

surprisingly "few reported injuries to show for possibly 75,000,000 yearly manipulations." (This appears to

be based on 3,000 per practitioner per year — 60 per week.) Livingstone does not specify whether his

calculations are based on a unilateral (single), or bilateral ( double) manipulation per visit. 18

In 1993, a Canadian study by Carey estimated that of 50,000,000 neck manipulations over a

five-year period, there were 13 serious YBA incidents and no deaths. 23 This is a VBA rate of

1:3,846,153. A U.S. insurance company has estimated the serious YBA rate at 1:2,000,000. 25

Table 3

REPORTED ACTIVITIES INVOLVING THE CERVICAL SPINE SUSPECTED OF

BEING INVOLVED WITH DISRUPTION OF CEREBRAL CIRCULATION*

Age not a factor 9

A bleeding nose 12,61

Angiography 43,62

Post-operative complications of thyroidectomy 82

Postural head changes 83,84

Radiographic procedure (VA angiography) 43

Archery (bow hunter) 12

Athletics 63

Axial traction 64

Backing up a car 44,62

Beauty parlour 65

Birth trauma 66 (see also 'childbirth')

Break dancing (see also rap dancing) 67-69

Calisthenics 70

Childbirth 'doubtful relationship' 55

Contraceptive pill 13,43

Coughing 71

Dental procedure 44

Diving into shallow water 72 (see 'falls')

During surgery 12

During x-ray examination 61

Emergency resuscitation 12

Falls (minor) 43

Falls causing hyperextension 43

Fitness exercise 71

Football 72-74

'Golden Gate Bridge' syndrome (sightseeing) 75

Gymnastics 70

Hair dressing 76

Hanging out washing 77

Head banging 43

Motor vehicle accidents 44

Neck callisthenics (Tai chi) 78

Ophthalmological perimetric visual examination 79

Overhead work 80

Painting ceiling 80,81

Rap dancing 67-69,85,86

Reversing a vehicle (see 'backing up')

Roller coaster 87,88

Self manipulation 'clicked on turning' 89

Self manipulation (rapid) 90,91

Sitting in a barber's chair 77

Sit-up exercises 24

Sliding head-first down a water slide 24

Sleeping positions 50

Spontaneous rupture of aneurisms 43

Spontaneous turning of head 40,44

Spontaneous vertebral artery dissection 9,40-46

Star gazing 16

Stooping to pick up a bucket 24

Surgery, neck positioning during anaesthesia 79

Swimming 92

Tai chi 78

Telephone call (cordless) 89

Traction of cervical spine 48,63,77

Traction and short wave diathermy 89

Trampoline 40

Trauma 94

Turning one's head 83

Turning one's head while driving 44,95

Under anaesthesia 12

Voluntary movement 96

Watching aircraft 77

Whiplash 72,96

Yawning & vigorous stretching (spinal artery) 97

Yoga ('Bridge' or 'Back push-up') 70,98

Yoga (rotating head) 98

* Adapted from Terrett 9,12,54,55

[Of tangential interest, Berger and Sheremata 99 observed persistent neurological deficits in suspected

multiple sclerosis patients; the signs were precipitated by a hot bath, They found that other aggravating

factors indicating this predisposition to acute exacerbation of signs included a lovers' quarrel and golf. The

reliability of the 'Hot Bath Test' was challenged by Davis. 100]

Table 4

REPORTED MANIPULATIVE SIDE EFFECTS ASSOCIATED WITH A

VARIETY OF OTHER PRACTITIONERS FROM DIVERSE BACKGROUNDS*

Physiotherapists 24,30,31,81,103,104

Osteopaths 77,105-107

Masseurs 54

Naturopaths 54

Medical practitioners 24,54

Kinesiotherapist 108

A barber 54

A kung-fu practitioner 54

A patient's own wife 109

Self manipulation 90,110

Unqualified practitioners designated to be 'chiropractors' without formal chiropractic education

11

Adapted from Terrett 54,55

Adverse Effects from Medical Procedures

There are morbidity and mortality incidents with most prescription and non-prescription drugs, as well as

with major and minor surgical procedures. Generally, these adverse events are far higher than manipulative

procedures. The mortality and morbidity rates of certain medical procedures can be viewed to gain a

perspective on the risks involved 113-116 (see Tables 5-7).

It would be grossly irresponsible and misleading if patients were led to believe that adverse effects from

medical procedures did not exist, or were disproportionately low. It is surprising how patients seem to accept

the incidence of risks and complications from medical procedures as "normal," yet still be alarmed at the

limited possibility and significantly lower adverse incident rates ("negligible" 24) involving manipulative

procedures in chiropractic or other professions using manipulation. Unwarranted sensationalism of cases

involving chiropractors threatens to create an impression out of proportion to the actual facts. One wonders

what would happen if all medical procedures were subject to the same levels of safety, efficacy, journalistic

scrutiny and particularly inaccurate publicity.

Issues concerning the efficacy of medical care have already been raised in such respected journals as the

Lancet, British Medical Journal, the Journal of the American Medical Association and the Medical Journal

of Australia. Such controversial issues do not appear to have received general media exposure or public

discussion to any great degree. 125,172-177

What should be of serious concern, however, is the statement in one of the world's most respected journals in

1991, the British Medical Journal:

"... only about 15% of medical interventions are supported by solid scientific evidence..." and "only 1 %

of the articles in medical journals are scientifically sound and partly because many treatments have

never been assessed at all. 174

Six years earlier, in 1985, medicine was already aware of the problem when Leeder wrote in the Medical

Journal of Australia:

"Much medical practice has escaped critical appraisal...many treatment schedules, new and old, simple and

complex, have been adopted and endorsed without firm evidence that they achieve more good than harm...

(or) have never been satisfactorily evaluated... Some procedures … became entrenched in professional

mythology long ago (and) have remained unchallenged despite their appalling cost in terms of human

suffering." 175

In 1998, Moore and colleagues noted two drugs which were shown to have serious and potentially lethal

cardiac side effects. They had been on the market for twelve and fourteen years, respectively. They stated:

"Discovering new dangers of drugs after marketing is common. Over 51 % of approved drugs have serious

adverse effects not detected prior to approval. Merely discovering adverse effects is not by itself sufficient to

protect the public." 176

The International Classification of Diseases code 178 lists the following iatrogenic classifications which

include numerous headings under "misadventure" and "complications":

E850-858 - Accidental poisoning and medication errors.

E870-879 - Misadventures during surgical and medical care.

E930-949 - Drugs causing adverse effects in therapeutic use.

E977.9

- Medicine poisoning by overdose- wrong substance given or taken in error.

E995.2 - Adverse effect, correct substance properly administered.

Adverse drug reactions rank as the fifth ("between fourth and sixth") leading cause of death in

the U.S. — 106,000 deaths in 1994. 125

In relation to medical complications, a 1982 study by Steel et al. found"... a 36% incidence of iatrogenic

illnesses among 815 consecutively selected patients in a tertiary care university hospital." In 2% (16.3 of those

admitted), " … these complications were believed to have contributed to death." 114 By 1998, Lazarou and

colleagues found that there was virtually no change in the incidence rate of adverse drug reactions in the 32

years of their study. 125

A two-year study by Rankin et al. (1990-1992) found that in Australia, "Between 170 and 850 (1-5%) strokes

occur (annually as) a major iatrogenic complication of cardiopulmonary by-pass surgery." 179 Other major

surgical procedures also carry the risk of stroke (see Table 8).

In 1993, Nachemson stated that in relation to spinal surgery, "... the clinical studies have largely lacked

validity: controlled, prospective tr1als are disappointingly rare." 182

These issues alone should_overshadow and create more concern than political medicine's preoccupation with

otherprofessions which it may see as competitors.

While medicine seems interested in highlighting incidents involving spinal manipulation, it can be questioned

as to whether patients are fully cognisant of the high rates of medical incidents. This is not intended as a

criticism, but more to place the rate of incidents in context. One cannot ignore the assumption of "acceptable

statistics" in the absence of public awareness.

Table 5

MORTALITY RATES OF VARIOUS MEDICAL

PROCEDURES AND DAILY EVENTS*

SURGERY

Appendectomies

1:74 5

Cervical spine surgery

1:145 5

Cholecystectomy

1:51-200 5,116

Colon surgery

Coronary bypass surgery (up to 21 % of patients who

experienced an adverse event resulted in a fatal

outcome)

1:14-50 5

Herniated disc surgery

1:481 117

Iatrogenic cardiac arrests

1:1.7 118

Iatrogenic esophageal perforations

1:3.5 119

Lumbar discectomy

.9:1000 120

Lumbar fusion

1:50-1400 111

Lumbar laminectomies

1:204 5

Lumbar surgery

1:683 121

1:263 34

Lumbar 'procedures'

1:1,430 122

Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty

Intracranial 16.7% mortality

1:6 123

Sciatic surgery

1:684 121

Small intestine surgery

1:4.76 5

DRUGS

Drug reactions

1:230 124

1:14.9 125

1:28 124

1:312.5 125

1:67 126

1:2.86 127

1:1103 28

Hospital deaths

Drug related problems (DRPs)

1:29 129

(1/3 'not preventable')

Adverse drug reaction (17.2%)

1:5.8 129

Taking a drug for which there was no valid

medical indication

1:5.8 129

Non-compliance (50%)

1:2 129

Medication error (out-patients) 1993

1:131 130

(in-patients) 1993

1:854 130

Anti-inflammatories

1 :63,333*

HOSPITAL ADMISSIONS

Iatrogenic paediatric admissions to intensive care

1:27 131

Iatrogenic adult intensive care admissions

1:41 132

Hospital iatrogenesis - 50,000-100,000 deaths due to

pulmonary embolism in hospitalised patients

annually in the US 133

1:50 114

RADIOLOGY

Nuclear bone scan

1:3,000 134

MEDICAL PROCEDURES

Venipuncture

1:25,000 1

Spinal manipulation

see Table 1

DISEASES/CONDITIONS

Ischaemic heart disease

162:100,000 1:617

Cerebrovascular disease

Cerebrovascular disease ('age adjusted') 135

70:100,000 1:1,429 38

38

(of population, not mortality rate of cases) 1988

Males

USA

1:1,739

Australia

1:1.226

Females

Greece

1:751

USA

1:1,984

Australia

1:1,355

Greece

1:725

1954

1:689

1993

1 :1,471

1954

1:593

1993

1:1,653

1996 37

1:1,429

Japan

1:1,873

Australia

1:366

Scotland

1:254

Japan

1:3,247

Australia

1:707

Scotland

1:511

Cerebrovascular disease (Australia) 135

Males

Females

Coronary heart disease ('age adjusted') 1983 135

Males

Females

CHRONIC DISEASES 1993 (Australia) 136

(per population, not morality rate of cases)

Coronary heart disease

1:624

136

Ischaemic heart disease 1996

1:617

135

Chronic obstructive airways disease 1996

1 :525(est) 135

Stroke

1:1,536

All cancers

1:555

136

136

1:704 135

Cancer - upper respiratory

1996

1:2,833 136

1:526 136

1996

Melanoma

1:21,277 136

Prostate cancer

1:2,841 136

1:7,143 (est.) 135 1996

1:3,718 136

Breast cancer

1:7,143 135 1996

1:4,098 136

Colorectal cancer

1:4,348 135 1996

1996

1:17 137

Incidence rate females 1996

1:27 137

Incidence rate males

Asthma

1 :23,256 136

Diabetes

1:7,143 136

HIV

1:1,770 136

RELATIVE RISKS DAILY CIRCUMSTANCES/

SPORT/INDUSTRY

Motor vehicle accidents

1:9,091 111 1996

Lightning strike

1 :200,000 138 (Hit by)

1 :600,000 111

1 :2,000,00o 139

Deaths

Homicide

1 :52,632 136

Acting in theatre

National workplace fatalities (Australia) 141

Injury

1:2.2 140

(597 deaths per year per no. of employees)

Forestry and logging

1:1,075

Fishing and hunting

1:1,163

Mining

1:2,778

Transport & storage

1:4,348

Agriculture

1:5,000

Construction

1:10,000

Rugby Union (participants)

1:5,000 139

Spinal cord injuries

1:6,250 142

Rugby Union

1:18,868 143

Rugby League

1 :55,556 143

Neurological deficits

1:16,667

Fatalities

1:15,000 139

Boxing fatalities (per contest)

142

1:10,000 144

* Estimation is based on 200 deaths each year in Australian population aione-all citizens including those not

taking NSAIDs = 200:19,000,000. 35 A more recent estimate Is based on '10%' of the 4,500 NSAID-related

upper gastrointestinal hospital admissions annually-between 200 and 400 deaths per annum. 145 Blower

estimates that NSAIDs could be responsible for 3,000 deaths in Great Britain. 146

Table 6

MORBIDITY RATES

ANAESTHESIA

General anaesthesia

1:1,103

174

Anaphylactoid anaesthetic reactions (restricted to life-threatening or

operation-disrupting)

1:1,000to 1:10,000

SURGERY

Atherosclerotic procedure-related complications

Idiopathic scoliosis surgery (adult)

1 :6 123

1 :2.44 minor 149

1 :4.4 serious

1:1.64 (51%) 150

Cardiac surgery

Chemonucleolysis 121

Cauda equina

New root deficits

Paraplegia

Allergic reaction to anaesthesia

Discectomy

Cauda equina

Sciatic surgery

'Wrong level'

Total complications

Lumbar disc re-operation

Successful (28%)

Repeat surgery for failed lumbar disc surgery

Percentage successful result of repeat:

Discotomy

Decompression

Stabilisation

Decompression & stabilisation

Repair of pseudoarthrosis & decompression

1:2,911

1:257

1:21,831

1:49

1 :27 120

1 :200 120

1:45

1:4

1:3.6

1:5.6

121

151

152

75.0%

27.8%

33.0%

50.0%

14.3%

DRUGS

Drug reactions

Daily use of aspirin 6% more likely to experience a stroke

111

1.67

147

25% of all reported drug reactions in the UK are associated with

NSAIDs, yet they comprise 5% of prescriptions. 153

MEDICAL

Venipuncture

Epidural (Depo-Medrol)

1 :25,000 1

1:40 - 1 :200 148

HOSPITAL

Hospital iatrogenesis

18%-30% of all hospitalised patients have a drug

reaction...resulting in doubling of hospital duration. 115

Iatrogenic paediatric admissions to intensive care

Drug complications

Surgical complication

Iatrogenic adult admissions to intensive care

Drug complications

Therapeutic error

Drug reactions

(30% of these have a second drug reaction)

1:2.78

114

1.22 131

1.22 1.68

1.23 1:77

1 :7.9 132

1:14

1:23

1:20-1:33

DISEASES/CONDITIONS — INCIDENCE 156

Measles

Pneumonia

Encephalitis

Measles-encephalitis-mortality

Brain damage

Breast cancer by age 70

After 5 or more years on HRT

VACCINATION

1.25

1:2,000

1 :20,000

1:5,000

1 :14 157

1:10 157

115

148

Diphtheria/Tetanus/Whole cell pertussis

Anaphylactic reaction

Severe reaction

Measles---€ncephalitis (expected recovery)

SPINAL MANIPULATION

VBA (non-fatal) - 'as low as'

SMT-related cauda equina syndrome

1 :50,000 4

1:2,000 4

1:1,000,000

4

1: 1,000,000 64

1:100,000,000 22

It is noted that while some of these intetentions do not necessarily compare directly with manipulative

therapies, they reflect the risk factors which exist with all procedures.

Table 7

MORTALITY AND MORBIDITY RATES OF OTHER MEDICAL PROCEDURES*

MORTALITY

Cervical manipulation

@ 1 :400,000 major

@ 1 :40,000 minor

Estimate only

General population (VBA-related deaths)

General surgery (30-day mortality #)

Orthopaedic surgery#

All surgery#

After adjustment for risk factors #

Total hip replacement

Peripheral vascular surgery

Otolaryngology surgery

Iatrogenic hospital admissions

Vaccination at wrong body location

Medication error (out-patients 1:131)

Misinterpretation of medical jargon in laboratory reports

Epidural anaesthesia

Hospital medication: Over-prescribed/ or never used

NSAIDs

MORBIDITY

0.00025% 11

0.0025% 49

0.000000096%**

0.00057% 11

5.6% 113

1.8% 113

1.2% - 5.4% 113

0.49% -1.53% 113

1.1 % 158

4.6% 113

2.9% 113

1.84%

36.0% 114

33% 159

.76% 130

80% 160

1.6% 161

16-20% 162

0.04% 16

Liposuction (US) — 100 deaths in the past 12 months 163

Adverse effects associated with traction, 164 ultrasound, 167 acupuncture, 168 intrathecal steroid injections, 169

and vaccination 4, 170-172 have all been reported.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------* Adapted from Khuri et al.

** Based on an approximate calculation as follows:

1 00,000 man_worldwide—all professions

X 100 average cervical manipulations per week (e.g. 2 procedures/patient visit, 50 patient visits/wk)

= 10,000,000 cervical manipulations/wk

= 520,000,000 per year

@ .5 deaths per year (see Table 1)

= mortality rate of 1:1,040,000,000 = 0.000000096%

Table 8

INCIDENCE OF STROKE ASSOCIATED WITH MEDICAL PROCEDURES

Australian population Deaths from stroke

Non-stroke comparisons 180

Cancer

Suicide 15-24 yr/age

Heart disease

Motor vehicle accidents

Cardiopulmonary by-pass surgery

Open-heart surgery

Coronary by-pass surgery

Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty 123

Intracranial

Stroke

TIA

Mortality

Extracranial (supraorbital)

Stroke

TIA

Restenosis

1:1,639

180

1:565

1 :4,000

1:690

1 :3,125

1-5:100 179

0.3% - 5.2%

6.1% 34

181

33.3%

22.2%

16.7%

1%

2%

5.9%

DISCUSSION

It is always a most unfortunate event for any patient to suffer any side effect from any procedure or accident,

regardless of which profession is concerned. One cannot help but feel empathy, regret and sadness for any

involved patient and their family. However, the degree of inherent risk associated with all health interventions

is distinct from professional negligence, which is unacceptable.

Due to the lack of "bias" 28, 183 or partiality of discussions raised on the issue of CVAs as a result of

manipulation, it may be reasonable to assume that by now most patients would be aware of the possible risks

associated with manipulative procedures.

The chiropractic profession is at the forefront in recognising the possible complications associated with SMT;

similar awareness should apply to all procedures. The established manipulative professions would seem to be

qualified to recognise and minimise the risk to potentially vulnerable patients exhibiting signs and/or

symptoms. Various studies on the topic have been published; these have been collated recently by Terrett,

who has published extensively on the subject. 55

The chiropractic profession actively seeks to keep practitioners aware of all aspects of risks. As well as

informative seminars and journal papers, chiropractors' basic training prepares them for preventive

iatrogenic considerations. This includes careful case history taking, learning pre-manipulative testing and

appropriate manipulative skills in the serious area of possible iatrogenic complications.

The chiropractic profession was recognised in a 1979 New Zealand government study as being the profession

best qualified to carry out spinal manipulative procedures. This independent study also found that "Spinal

manual therapy in the hands of a registered chiropractor is safe." 184

It is quite irresponsible for medicine to condemn spinal manipulation when the potential for incidents is, by

its own standards, extremely rare. Even diagnostic investigations have a risk/benefit ratio. 39,114,134 The

double standard is evident when in fact generally, drugs and surgical procedures have risks of side effects with

a significantly higher fatality rate than spinal manipulation. It has been stated that "... all medications, even

so-called natural, can cause adverse reactions." 185

Because of medicine's self-serving publicity about SMT, discerning patients may see through what appears to

be the charade of biased scaremongering. Nevertheless, the demand for qualified manipulative care continues

to expand. A significant proportion of the population — almost 50% 186 of patients — actively seek an

appropriate alternative approach to their health problems. One must assume this option is exercised either as

a preference, a search for results, or choosing not to accede to chemical or surgical intervention.

In 1998, Wilks expressed surprise at the limited exposure of a 1987 American federal court finding that the

American Medical Association "... was dishonest, untrustworthy (and) not objectively reasonable" when it

acted to neutralise the competition and influence of chiropractic on the health care scene. 187 The referenced

literature and media similarly appear to have been noticeably reticent on this particular issue of a single

profession's (medicine's) domination of the entire health field. Strangely the media, and society in general, do

not appear to want to seriously question medical philosophy, paradigm, monopolisation, efficacy, costs or

procedures. 188

Medicine has adopted terms suggesting procedures have an "acceptable risk." These include "risk-adjusted

mortality rates," "net clinical benefit" and "risk/benefit ratio," yet there seems a reluctance to concede the

application of these terms to procedures outside the medical profession. 172 It seems that at times "such rates

have been condoned" — at least in relation to dural puncture, 189 or in immunisation programs where "the

benefits of preventing the disease far outweigh the risks of vaccination." 172

Lack of Government Standards or Guidelines

Regardless of the low rate of incidents in the manipulative sciences, the material reviewed warrants advocacy

of further caution and awareness, with continued endeavours towards risk elimination. It is fundamental for

the manipulative professions to maintain the maximum available level of recognised safety, training and

education before employing their conservative manipulative procedures. 190

As mentioned, although some SMT-related accidents may be unforeseen, 28,61,191 for the vast majority there

are procedures for both recognising and determining patients at risk. Essential education has been

established for this purpose.

Despite the importance of public interest in standards of care, the Australian state legislatures have created a

distinct anomaly through standardisation and mutual recognition of registration acts for health professions.

For instance, the Victorian government's Chiropractors Registration Act and the Osteopathic Registration Act

have, through an implication by considered omission, sought no standards or requirements placed upon

unregistered practitioners who attempt spinal manipulation. 192 That is, any person in Victoria may carry out

neck manipulation so long as he does not present himself as a chiropractor, osteopath, physiotherapist or

medical practitioner.

Australian state governments do not require minimal training standards for the manipulative procedures

utilised by non-registered practitioners — only for registered manipulative professionals who specialise in the

field. This also allows medical practitioners to attempt to manipulate the spine, even if they have no training

whatsoever in the procedures. This would seem incongruous when "protection of the public" and "standards"

were two of the primary criteria for establishing registration for the manipulative professions in the first place,

as would seem to be the case with all health professions. 193-195

Such a fundamental safeguard would seem even more important in health care where primary contact care

practitioners are responsible for the diagnosis as well as the safe and effective management of patients'

welfare and health problems. As has been indicated earlier, practitioners not formally trained or qualified in

SMT have been associated with incidents of CVAs 54,111 (see Table 4).

The kind of legislative policy that currently exists would tend to support the questionable assertion that

practitioners need not be qualified to render SMT, that there is relatively little concern for any danger from

any SMT side-effects, or indeed, that there is any perceived danger at all.

SUMMARY

While there are some stated limitations to this type of review, a number of matters were discussed in

attempting identify related issues:

The rate of adverse effects, namely cerebrovascular accidents related to spinal manipulative therapy, was

shown to be extraordinarily low in the overall health care scene.

The rate of SMT-related CVAs associated with the chiropractic profession is lower than for osteopathy and

medicine. Figures could not be determined for physiotherapy.

In general terms, the rate of SMT-related CVA is also lower than the rate of strokes in the general

population.

Morbidity and mortality rate of S MT is far lower than that suffered by patients taking NSAIDs.

There are both identifiable and unidentifiable anomalies, weaknesses, diseased states and conditions

which can influence the incidence of apoplexy in society.

There is a significant percentage of spontaneous apoplexy in the general population, and therefore, at

times, such a high "natural" frequency could be confused as an SMT-related incident.

The rate of preventable drug- and surgery-related iatrogenic illness in medicine is generally far higher

than for SMT, demonstrating SMT to be a safe and conservative form of intervention by comparison.

The rate of vertebrobasilar accidents associated with manipulation has been grossly exaggerated,

inaccurate and sensationalised by some ill-informed sources.

SMT in the hands of a practitioner properly qualified in this specialty is shown to be a particularly safe

procedure.

There appear to be medico-political overtones to the subject of SMT-related iatrogenesis.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper has attempted to identify perspectives of iatrogenesis and contrast levels of morbidity and

mortality with a number of elements which may adversely affect health. In drawing such comparisons, it is

worthwhile to understand where SMT is situated in relation to complications related to other forms of

intervention.

It is incumbent upon practitioners of all professions to be aware of the risks involved in every type of

procedure. Patients are also entitled to accurate information about the procedures that may be utilised in the

course of their care. Not only do practitioners have a role in providing this information, but the scientific

literature, as well as the printed and electronic popular media who report any adverse incidents must be

responsible and accurate in this duty.

This review of the evidence has indicated that a potential risk of catastrophic side-effects from SMT is

substantially less than for any of the medical procedures or interventions listed in the tables accompanying

this paper.

It is submitted that as reflected in the demand for therapy, spinal manipulation has contributed significantly

to the health and well-being of much of the world's population. Unsubstantiated published opinions and socalled scientific distortions of the facts are irresponsible. There are no "double-blind controlled scientific

studies" which reject a reasonable degree of efficacy of spinal manipulation for appropriate mechanical back

and neck conditions — indeed, quite the opposite. 196-199

In conducting this study it has been shown that the distorted impression of risk associated with cervical spinal

manipulation should be cast in the proper and minimal perspective which is its due. It would be hoped that

any reservations which dissuade qualified practitioners from utilising cervical spinal manipulation in

appropriate situations, or dissuades patients from accepting and subsequently benefiting from such

techniques, would be mitigated, and the rationale for the therapy better understood.

If medicine is to assume a scientific role, it must also record accurately, fairly and without prejudice on such

scientific matters concerning health and welfare. In this author's opinion, it is demonstrably wrong and

scurrilous to portray SMT as a highly dangerous procedure — both in its own right, and in light of the facts

concerning other procedures. It is both a judicious and propitious procedure which is safe by comparison and

may perhaps explain medicine's increasing interest in adopting SMT as one of its own regimes.

As inferred by Assendelft et al., 28 it is up to the properly informed patient and practitioner to compare the

risk/benefit ratio in choosing to seek relief through a particular type of intervention. To this end, conservative

procedures like spinal manipulation would appear to have a distinct advantage due to there inherently low

risk.

Without wishing to diminish the importance and serious nature of cardiovascular incidents related to SMT,

and with due recognition for continued caution for its potential, the miniscule risk which may be associated

with SMT is extraordinarily low and should be encouraged and endorsed as a safe front-line health procedure.

It has been suggested here that there is a relatively high incidence of CVA in the general population, that there

can be a number of predisposing conditions related to CVAs, that spontaneous CVAs are relatively common,

and that there can be a number of common activities associated with CVAs.

The professions who utilise spinal manipulation must strive for continued minimisation of possible SMTrelated side effects — indeed, their elimination — but the facts and statistics presented here suggest that given

the nature of its considered neural influence, and with all the information in perspective, spinal manipulation

in the hands of an appropriately qualified professional is both conservative and one of the safest therapeutic

procedures.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author gratefully appreciates the assistance provided by Dr Damon Willmore for his input and assistance

in the preparation of this paper.

REFERENCES

1.

Horowitz SH. Peripheral nerve injury and causalgia secondary to routine venipuncture.

Neurol 1994; 44: 962-964

2. Caswell A, editor. MIMS Annual, Australian edition.. 22nd ed. St Leonards, NSW:

MediMedia Publishing, 1998

3. Anon. Readers' Q & A. Aust Med 1998; Oct 5: 18

4. Burgess MA, Mcintyre PB, Heath TC. Rethinking contradictions to vaccination. Med J Aust 1998; 68:

476-477

5.

Stremple JF, Boss DS, Davis CH, McDonald GO. Comparison of post-operative mortality and morbidity

in Veteran Affairs and non-federal hospitals. J Surg Res 1994; S6: 405-416 [Cited by Willmore 115]

6. Toy M-A. Vision for laser surgery loses its shine—Seeing is believing. The Age, Melbourne 1998;

Nov 7: 15

7.

European Carotid Surgery Trialists' Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of endarterectomy for

recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: Final results of the MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST).

Lancet 1998; 351: 1379-1387

8. White WH. Strokes and net clinical benefit. Aust NZ J Med 1993; 23: 737-738

9. Terrett AGJ. Vascular accidents from cervical spine manipulation: Report of 107 cases. J Aust Chiropr

Assoc 1987; 17: 15-24

10. Donnana G. Strokes to rise. The Herald Sun, Melbourne 1998; Sept 30: 26

11. Myler L. A risk assessment of cervical manipulation vs. NSAIDs for the treatment of neck pain [letter].

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1996; 19:357

12. Terrett AGJ. Contraindications to cervical spine manipulation. In: Giles LFG, Singer KP, editors.

Clinical anatomy and management of cervical spine pain. Oxford: Butterworth-Heineman, 1998: 182-210

13. Mas JL, Bousser MG, Hasboun D, Laplane D. Extracranial vertebral artery dissection: A review of 13

cases. Stroke 1987; 18: 1037-1047

14. Fraser RAR, Zimbler SM. Hindbrain stroke in children caused by extracranial vertebral artery trauma.

Stroke 1975; 6: 153-159

15. Frumkin LP, Raloh Rw. Wallenberg's syndrome following neck manipulation. Neurol 1990; 40: 611-615

16. Dabbs V, Lauretti WJ. A risk assessment of cervical manipulation vs NSAIDs for the treatment of neck

pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1995; 18: 530-536

17. Cyriax J. Text-book of orthopaedic medicine. Vol 1: Diagnosis of soft tissue lesions. 4th ed. London:

Cassell, 1963: 174

18. Livingstone MCP. Spinal manipulation in medical practice: A century of ignorance. Med J Aust 1968; 1:

552-555

19. Maigne R. Orthopaedic medicine: A new approach to vertebral manipulations. Springfield: Charles C.

Thomas, 1972: 169

20. Jaskoviak PA. Complications arising from manipulation of the cervical spine. J Manipulative Physiol

Ther 1980; 3: 213-219

21. KJougart N, Leboeuf-Yde C, Rasmussen LR. Safety in chiropractic practice. Part 1. The occurrence of

cerebrovascular accidents after manipulation to the neck in Denmark from 1978-1988. J Manipulative

Physiol Ther 1996; 19: 371-377

22. Shekelle PG,Adams AH, Chassin MR, Hurwitz EL, Brook RH. Spinal manipulation for back pain. Ann

Intern Med 1992; 117: 590-598

23. Carey PF. A report on the occurrence of cerebral vascular accidents in chiropractic practice. J Can

Chiropr Assoc 1993; 37: 104-106

24. Haynes MJ. Stroke following cervical manipulation in Perth. Chiropr J Aust 1994; 24: 42-46

25. Lauretti WJ. Spinal manipulation [letter]. J Fam Pract 1996; 43: 333-334

26. Lauretti WJ. Chiropractic complications [letter]. Neurol 1996; 46: 884

27. Michaeli A. Reported occurrence and nature of complications following manipulative physiotherapy in

South Africa. Aust Physiother 1993; 39: 309-315

28. Assendelft WJJ, Bouter LM, Knipschild PG. Complications of spinal manipulation. A comprehensive

review of the literature. J Fam Pract 1996; 42: 475-480

29. Tauro J. Chiropractic complications [letter]. Neurol 1996; 46: 884

30. Michaeli A. Spinal manipulation by physiotherapists in South Africa: Result of a questionnaire.

Physiother 1992; 78: 673-678

31. Michaeli A. Dizziness testing of the cervical spine: Can complications of manipulations be prevented?

PhysiotherTheor Pract 1991; 7: 243-250

32. Carter H. Chiropractic found to ease brain injury. Herald Sun, Melbourne 1998; Sept 30: 30

33. Carrick FR. Changes in brain function after manipulation of the cervical spine. J Manipulative Physiol

Ther 1997; 20: 529-545

34. Roach GW, Kanchuger M, Mangano CM, Newman M, Nussmeier N, Wolman R, et at. Adverse cerebral

outcomes after coronary bypass surgery. New Engl J Med 1996; 335: 1857-1863

35. Cooke J. Cutback on fatal arthritis drugs. Sydney Morning Herald 1992; Nov 18: 12

36. Carter H. Hopes on safer arthritis drug. Herald Sun, Melbourne 1998; Jan 6: 9

37. Woodward M. Preventing strokes. Veterans' Health. Newsletter from the Department of Veterans' Affairs,

Canberra 1997; 61: 18-20

38. Anon. Causes of death in Australia, 1996. Med J Aust 1998; 169: 5

39. HankeyGJ. Transient ischaemic attacks. MedJAust 1995; 162: 260-263

40. Hart RG. Vertebral artery dissection. Neurology 1988:38: 987-989

41. Mokri B, Houser OW, Sundt AM. Idiopathic regressing anteriopathy. Ann Neurol 1977; 2: 466-472

42. Mokri B, Houser OW, Sandok BA, Pipgras DG. Spontaneous dissections of the vertebral artery. Neurol

1988; 38: 880-885

43. Mas J-L, Goeau C, Bouser M-G, Chiras J, Verret J-M, Touboul P-J. Spontaneous dissecting aneurysms of

the internal carotid and vertebral arteries: Two case reports. Stroke 1985; 16: 125-129

44. Sherman DG, Hart RG, Easton JD. Abrupt change in head position and cerebral infarction. Stroke 1981;

12: 2-6

45. Schievink WI, Mokri B, O'Fallon WM. Recurrent spontaneous cervical artery dissection. New Engl J Med

1994; 330: 393-397

46. Swenson RS. Spontaneous vertebral artery dissection: A case report. J Neuromusculoskeletal Syst 1993

(1): 10-3

47. Drake M. Cricket ball death was freakish, says coroner. The Age, Melbourne 1987; June 11: 7

48. Kaufman HH, Harris JH, Spencer JA, Kopansky DR. Danger of traction during radiography for cervical

trauma [letter]. JAMA 1982; 247:2369

49. Leach RA. The chiropractic theories: Principles and clinical applications. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Williams and

Wilkins, 1994:285-97

50. Hope EE;-Bodensteiner JB, Barnes P. Cerebral infarction related to neck position in the adolescent.

Pediatr 1983; 72:335-7

51. Husni EA, Bell\HS, Storer J. Mechanical occlusion of the vertebral artery. A new clinical concept. JAMA

1966; 196: 475-478

52. Husni EA, Storer J. The syndrome of mechanical occlusion of the vertebral artery: Further observations.

Angiology 1967; 18: 106-16

53. Hardin CA, Poser CM. Rotational obstructions of the vertebral artery due to redundancy and extraluminal

fascial bands. Ann Surg 1963; 158: 133-137

54. Terrett AGJ. Misuse of the literature by-medical authors in discussing spinal manipulative therapy injury.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1995; 18: 203-210

55. Terrett AGJ. Vertebrobasilar stroke following manipulation. West Des Moines, IA: National Chiropractic

Mutual Insurance Company, 1996

56. McKechnie B. Manipulative vascular accidents in proper perspective. Part I: Dynamic Chiropr 1994; 12

(16): 25, 37. ~ and ~ Part II: Dynamic Chiropr 1994; 12 (18): 28-9

57. Silverstein A, Present DH. Cerebrovascular occlusions in relatively young patients with regional enteritis.

JAMA 1971; 215: 976-977

58. Nelson J, Barron MM, Riggs JE, Gutmann L, Schochet S. Cerebral vasculitis and ulcerative colitis. Neurol

1986; 36: 719-721

59. Yassinger S, Adelman R, Cantor D, Halsted CH, Bolt RJ. Association of inflammatory bowel disease and

large vascular lesions. Gastroenterol 1976; 71: 844-846

60. Sturzenegger M. Headache and neck pain: The warning symptoms of vertebral artery dissection.

Headache 1994; 34: 187-193

61. Fogelholm R, Karli P. 'Iatrogenic' brain stem infarction. A complication of x-ray examination of the

cervical spine and following posterior tamponade of the nose. Eur Neurol 1975; 12: 6-12

62. Yang PJ, Latack JT, Gabrielsen TO, Knake JE, Gebarski SS, Chandler, et al. Rotational vertebral artery

occlusion at C 1-C2. Stroke 1985; 6: 98-100

63. Zimmerman AW, Kumar AJ, Gadoth N, Hodges FJ. Traumatic vertebrobasilar occlusive disease in

childhood. Neurol 1978; 28: 185-188

64. Hamann G, Haass A, Kujat C, Felber S, Strittmatter M, Schimrgk, ef al. Cervicocephalic artery dissections

due to chiropractic manipulations [letter]. Lancet 1993; 341 : 764-765

65. Weintraub MI. Beauty .Parlour stroke syndrome: Report of five cases. JAMA 1993; 269: 2085-2086

66. Yates PO. Birth trauma to the vertebral arteries. Arch Dis Child 1959; 34: 431-436

67. Dorey RSA, Mayne V. Break-dancing injuries [letter]: Med J Aust 1986; 144: 610-611

68. McBride DO, Lehman CP, Mangiardi JR. Break-dancing neck. New Engl J Med 1985; 312: 186

69. Leung AK. Hazards of breakdancing. NY State J Med 1984; 84: 592

70. Nagler W. Vertebral obstruction by hyperextension of the neck: A report of three cases. Arch Phys Med

Rehabil 1973; 54: 237-240

71. Pryse-Phillips W. Infarction of the medulla and cervical cord after fitness exercises. Stroke 1989; 20:

292-294

72. Schneider RC, Schemm GW. Vertebral artery insufficiency in acute and chronic spinal trauma. J

Neurosurg 1961; 18: 348-360

73. Weinstein SM, Cantu RC. Cerebral stroke in a semi-pro football player: A case report. Med Sci Sports

Exerc 1991; 23: 1119-1121. [Cited by Terrett 12]

74. Marks RL, Freed MM. Non-penetrating injuries of the neck and cerebrovascular accident. Arch Neurol

1973; 28: 412-414

75. Boldrey E, Maas L, Miller E. The role of allantoid compression in the etiology of internal carotid

thrombosis. J Neurosurg 1956; 13: 127-139

76. Nwokolo N, Bateman DE. Stroke after a visit to the hairdresser. Lancet 1997; 350: 866

77. Brown BStJ, Tallow WFT. Radiographic studies of the vertebral arteries in cadavers: Effects of posture

and traction on the head. Radiol 1963; 81: 80-88

78. Oh VMS. Brain infarction and neck callisthenics. Lancet 1993; 342: 739-740

79. Tettenborn B, Caplan LR, Sloan MA, Estrol CJ, Pessin MS, DeWitt LD, et al. Post-operative brainstem

and cerebellar infarcts. Neurol 1993; 43: 471-477

80. Okawara S, Nibbelink D. Vertebral artery occlusion following hyperextension and rotation of the head.

Stroke 1974; 5: 640-642

81. Fritz VU, Malon A, Tuch P. Neck manipulation causing stroke. S Afr Med J 1984; 66: 844-846

82. Wagner M, Kitzerow E, Taitel A. Vertebral artery insufficiency. Arch Surg 1963; 87: 885-886

83. Tallow WIT, Bammer HG. Syndrome of vertebral artery compression. Neurol 1957; 7: 331-340

84. Grossman RI, Davis KR. Positional occlusion of the vertebral artery: A rare cause of embolic stroke.

Neuroradiol 1982; 23: 227-230

85. Norman RA, Grodin MA. Injuries from break-dancing. Am Fam Physician 1984; 4: 109-112

86. Gascoemsio PJ, Leurauos L. Injury caused by break-dancing. JAMA 1984; 252: 3367

87. Biousse V, Chabriat H, Awarenco P. Roller-coaster-induced vertebral artery dissection (letter]. Lancet

1995; 346: 767

88. Bo-Abbas Y, Bolton CF. Roller-coaster headache. New Engl J Med 1995; 332: 1585

89. Brain L. Some unsolved problems of cervical spondylosis. Br Med J 1963; 1: 771-777

90. CookJW, SansteadJK. Wallenberg's syndrome following self-induced manipulation. Neurol 1995; 41:

1495-1496

91. Schellhas KP, Latchaw RE, Wendling LR, Gold HA. Vertebrobasilar injuries following cervical

manipulation. JAMA 1980; 244: 1450-1453

92. Tramo MJ, Hainline B, Petito F, Lee B, Caronna J. Vertebral artery injury and cerebellar stroke while

swimming: Case report. Stroke 1985; 16: 1039-1042

93. Mourad J-J, Giererd X, Safar M. Carotid artery dissection after a prolonged telephhone call [letter]. New

Engl J Med 1997; 333: 516

94. Klein RA, Snyder RD, Schwartz HJ. Lateral medullary syndrome in a child: Arteriographic conformation

of vertebral artery occlusion. JAMA 1976; 235: 940-941

95. Easton JD, Sherman DG. Cervical manipulation and stroke. Stroke 1977; 8: 594-597

96. Simeone FA, Goldberg HI. Thrombosis of the vertebral artery from hyperextension injury to the neck.

Case report. J Neurosurg 1968; 29: 540-544

97. Grinker RR, Guy Cc. Sprain of cervical spine causing thrombosis of anterior spinal artery. JAMA 1927; 88:

1140-1142

98. Hanus SH, Homer TD, Harter DH. Vertebral artery occlusion complicating yoga exercises. Arch Neurol

1977; 34: 574-575

99. Berger JR, Sheremata WA. Persistent neurological deficit precipitated by hot bath test in multiple

sclerosis. JAMA 1983; 249: 1751-1752

100.

Davis FA. Neurological deficits following the Hot Bath Test in multiple sclerosis. JAMA 1985;

253: 203

101.

De Fabio RP. Manipulation of the cervical spine: Risks and benefits.

102.

Winterstein JF. Spinal manipulation [letter]. J Fam Pract 1996; 43: 333

Phys Ther 1998; 79: 50-65

103.

Michaeli A. Reported occurrence and nature of complications following manipulative physiotherapy

in South Africa. Aust Physiother 1993; 39 (4): 309-315

104.

Parker PJ, Wallis WE, Wilson JL. Vertebral artery occlusion following manipulation of the neck. NZ

Med J 1978; 88: 441-443

105.

Lyness SS, Wagman AD. Neurological deficit following cervical manipulation. Surg Neurol 1974; 2:

121-124

106.

Danesmend TK, Hewer RL, Bradshaw JR. Acute brain stem stroke during neck manipulation. Br

Med J 1984; 288: 189

107.

Cooper G. Osteopathic manipulation resulting in damage to spinal cord. Br Med J 1985; 291:

1538-1541

108.

Tauro J Chiropractic complications (letter]. Neurol 1996; 46: 884

109.

Ford FR, Clark D. Thrombosis of the basilar artery with softenings in the cerebellum and brain stem

due to manipulation of the neck. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp 1956; 98: 37-42

110.

Rothrock JF, Hesselink JR, Teacher TM. Vertebral artery occlusion and stroke from cervical selfmanipulation. Neurol 1995; 41 : 1496-1497

111.

Bohm J. Cervicocephalic artery dissections due to chiropractic manipulations (letter]. Lancet 1993;

341: 1214

112. Terrett AGJ. Personal communication, August 1998

113. Khuri SF, Daley J, Henderson W, Hur K, Gibbbs JO, Barbour G, el at. Risk adjustment of the postoperative mortality rate for the comparison assessment of the quality of surgical care. Results of the

National Veterans Affairs surgical risk study. J Am Coli Surg 1997; 185: 315-340

114. Steel K, Gertman PM, Crescenzi C,Anderson J. Iatrogenic illness on a general medical service at a

university hospital. New Engl J Med 1981; 304: 638-642 Cited in: Iatrogenic Illness: How frequently

does it occur? [extracts]. Mod Med Aust 1982; July: 51

115. Willmore D. You're in safe hands: The relative risks of chiropractic care. Unpublished research 1998

116. Steiner CA, Bass EB, Talamini MA, Pitt HA, Steinberg EP. Surgical rates and operative mortality for

open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy in Maryland. New Engl J Med 1994; 330: 403-408 (cited by

Willmore 115)

117. Stolke D, Sollman WP, Seifert V. Intra-and post-operative complications in lumbar disc surgery. Spine

1989; 14: 56-58

118. Bedell SE, Deitz DC, Leeman D, Delbanco TL. Incidence and characteristics of preventable iatrogenic

cardiac arrests. JAMA 1991; 265: 2815-2820

119. Bellestra-Lopez C, Vallet-Fernandez J, Catarci M, Bastida-Vila X, Nieto-Martinez B. Iatrogenic

perforations of the esophagus. Int Surg 1993; 78: 28-31 (cited by McKechnie 55)

120.

Kardaun JW, White LR, Shaffer WO Acute complications in patients with surgical treatment of

lumbar herniated disc. J Spinal Disorders 1990; 3 (1): 30-38

121.

Bouillet R. Treatment of sciatica. A comparative survey of complications of surgical treatment and

nucleolysis with chymopapain. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1990; 251: 144-152

122.

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Loeser JD, Bigos SJ, Ciol MA. Morbidity and mortality in association with

operations on the lumbar spine. J Bone Jt Surg 1992; 74-A: 5536-5543

123.

Volk EE, Prayson RA, Perl J. Autopsy findings of fatal complications of posterior cerebral circulation

angioplasty. Arch Path Lab Med 1997; 121: 738-740

124.

Shapiro S, Slone D, Lewis GP, Jick H. Fatal drug reactions among medical patients. JAMA 1971;

216: 467-472

125.

Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients. A

meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA 1998; 279: 1200-1205

126.

Borda IT. Assessment of adverse reactions within a drug surveillance program. JAMA 1968; 205 (9):

99-101

127.

Wang RIH, Terry Lc. Adverse drug reactions in a veterans administration hospital. J Clin Pharmacol

1971; 11: 14-18

128.

Porter J, Jick H. Drug-related deaths among medical inpatients. JAMA 1977; 237: 879-881

129.

East KL, Parsons BJ, Starr M, Brien JE. The incidence of drug-related problems as a cause of hospital

admissions in children. Med J Aust 1998; 169: 356-359

130.

Phillips DP, Christenfeld N, Glynn LM. Increase in US medication error deaths between 1983 and

1993. Lancet 1998; 351 : 643-644

131.

Stamouly JP, Pollack MM. Iatrogenic illnesses in pediatric critical care. Crit Care Med 1990; 18:

1248-1251 (cited by McKechnie 55)

132.

Trunet P, Le Gall J-R, Lhoste F, Regnier B, Saiilard Y, Carlet J, et al. The role of iatrogenic disease in

admissions to intensive care. JAMA 1980; 244: 2617-2620

133.

King M. Preventing deep venous thrombosis in hospitalised patients. Am Fam Physician 1994; 49:

1389-1396

134.

135.

Roebuck DJ. Diagnostic imaging: Reversing the focus [letter]. Med J Aust 1995; 162: 275

D'Espaignet ET. Trends in Australian mortality. In: Diseases of the circulatory system: 1950-1991.

Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1994:49-64

136.

Abraham B, d'Espaignet ET, Stevenson C. Australian health trends 1995. Canberra: Australian

Institute of Health and Welfare, 1995: 34-47

137.

Anon. Colorectal cancer. Med J Aust 1998; 169: 5

138.

Heywood J, Carson A. Lightning sparks bushfire havoc across state. The Age, Melbourne 1998; Dee

26:3

139.

Maharaj JC, Cameron D. Increase in spinal injury among rugby union players in Fiji [letter]. Med J

Aust1998; 168: 418

140.

141.

Anon. Break a leg. Med J Aust 1998; 169: 442 (citing Occup Environ Med 1998; 55: 585-593)

Trinca H. Work accidents kill 11 a week. The Age, Melbourne 1998; Dee 7: 5 (citing a National

Occupational Health and Safety Commission Survey 1988-1992)

142.

Rotem TR, Lawson JS, Wilson SF, Engel S, Rutkowski SB, Aisbett CW Severe cervical spinal cord

injuries related to rugby union and league football in New South Wales, 1984-1996. Med J Aust 1998;

168: 379-381

143.

Wilson SF, Atkin PA, Totem T, Lawson J. Spinal cord injuries have fallen in rugby union players in

New South Wales [letter]. Br Med J 1996; 313: 1550

144.

145.

Pearn J. Reducing brain damage in boxers [letter]. Med J Aust 1998; 168: 418

Day RO, Rowett D, Roughhead EE. Towards the safer use of non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

J Qual Clin Pract 1999; 19: 51-53

146.

Blower AL, Armstrong CP Ulcer perforation in the elderly and non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Lancet 1986; 1 : 971

147.

Tuchin P.

Manual therapy carries low risk. Aust Doctor 1997; Feb 7: 5

148.

Laxenaire MC, Moneret-Vautrin DA, WatkinsJ. Diagnosis and causes of anaphalactoid anaesthetic

reactions. Anaesth 1983; 38: 147-148

149.

Sponseller PD, Cohen MS, Nachemson AL, Hall JE, Wohl EB. Results of surgical treatment of adults

with idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Jt Surg 1987; 69-A: 667-675

150.

Tettenborn B, Caplan LR, Sloan MA, Estol CJ, Pessin MS, DeWitt LD, et al. Post-operative

brainstem and cerebellar infarcts. Neurol 1993; 43: 471-477

151.

Law JD, Lehman RAW, Kirsch WM. Re-operation after lumbar intervertebral disc surgery. J

Neurosurg 1978; 48: 259-263

152.

Waddell G, Kummel EG, Lotto WN, Graham JD , Hall H, McCulough JA. Failed lumbar disc surgery

and repeat surgery following industrial injuries. J Bone Jt Surg 1979; 61-A: 201-207

153.

Gomes JA, Roth SH, Zeeh J, Bruyn GAW, Woods EM, Geis GS. Double-blind comparison of efficacy

and gastroduodenal safety of diclofenac/misoprostol, piroxicam, and naproxen in the treatment of

osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1993; 52: 881-885

154.

Tress B, Lau L.

155.

Melmon KL. Preventable drug reactions--causes and cures. New Engl J Med 1971; 284: 1361-1368

156.

Lally G. Cause for concern. Herald Sun, Melbourne 1998; July 7: 5

157.

Depo-Medrol and facet joint injections Australasian Radiol 1991; 35: 291

Auchincloss S. Facts a casualty in medicine. Onus on doctors to keep up to date with research. Aust

Doctor 1998; Oct 23: 27

158.

Seagroat V, Tan HS, Goldacre M, Bulstrode C, Nugent I, Gill L. Elective total hip replacement:

Incidence, emergency readmission rate, and post-operative mortality. Br Med J 1991; 330: 1431-1435

159.

Dow S. Vaccination report needles GPs. The Age, Melbourne, 1995; Mar 11

160.

Lee A. Doctors fooled by lab reports: A Survey. The Age, Melbourne circa 1978

161.

MacArthur C, Lewis M, Knox EG. Accidental dural puncture in obstetric patients and long term

symptoms. Br Med J 1993; 306: 883-885

162.

Miller BM. Hospital drug error rate 'seriously high'. The Age, Melbourne 1979; Oct 2

163.

Marshall D. Liposuction warning. Quoted in The Herald Sun, Melbourne 1998; Sept 30: 26

164.

Horsley M, Taylor TK, Sorby WA. Traction induced rupture of an extracranial vertebral artery

aneurysm associated with neurofibromatosis: A case report. Spine 1997; 22: 225-227

165.

Gruenberg MF, Rechtine R, Chrin AM, Sola CA, Ortulan EG. Overdistraction of cervical spine

injuries with the use of skull traction: A report of 2 cases. J Trauma 1997; 42: 1152-1156

166.

Simmers TA, Bekkenk MW, Vidakovic-Vukic M. Internal jugular vein thrombosis after cervical

traction. J Intern Med 1997; 241 : 333-335

167.

Ter Haar G. Safety of diagnostic ultrasound [commentary]. Br J Radiol 1996; 69: 1083-1085

168.

Norheim AJ, Fonnebo V. Adverse effects of acupuncture [letter]. Lancet 1995; 345: 1576

169.

Rochel J. Steroid-induced arachnoiditis. Med J Aust 1984; 140, 281-284

170.

Chen RT, De Stefano F. Vaccine adverse events: Causal or coincidental? Lancet 1998; 351: 611-612

171. Brown MA, Bertouch JV. Rheumatic complications of influenza vaccination. Aust NZ Med J 1994; 24:

572-573

172.

Duclos P, Bentsi-Enchill A. Risks and benefits of immunisation. Current Thoughts. Curr Ther 1994;

April: 17-28

173.