COTM0913 - California Tumor Tissue Registry

advertisement

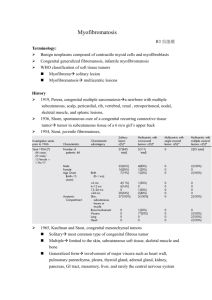

“A Four Day Old Infant Boy With a Forehead Lesion” California Tumor Tissue Registry’s Case of the Month CTTR COTM Vol. 15:12 September, 2013 www.cttr.org A four day old infant boy underwent a biopsy of a firm 2.5 x 1.0 cm purplish macule on his forehead. Microscopically the lesion showed a nodular growth pattern and biphasic zonality with an abrupt interface between the central hypercellular component and peripheral paucicellular component (Figs. 1, 2). Higher power views of the central region showed a hemangiopericytoma-like pattern with abnormal staghorn vessels (Figs. 3, 4). The hypocellular region around the perimeter showed spindled eosinophilic cells with a fascicular growth pattern, resembling smooth muscle cells or myofibroblasts (Figs. 5, 6). A small area of necrosis and calcification was present (Fig. 7). Diagnosis: Myofibroma (Myopericytoma) Summer Blount MD, Donald R. Chase MD Department of Pathology and Human Anatomy, Loma Linda University Medical Center, Loma Linda, California California Tumor Tissue Registry, Loma Linda, California Although myofibromatosis was initially described in 1951 by Williams and Schrum as a type of congenital fibrosarcoma, the entity was quickly reclassified by Stout as congenital generalized fibromatosis when it was shown that this tumor lacked malignant potential. Chung and Enzinger later noted that the cellular makeup was primarily of myofibroblasts and renamed the lesion “infantile myofibromatosis”, and adopted the term “myofibroma” when the lesion was solitary. Later, the term “infantile” was dropped in recognition that these tumors may occur later in life. The 1998 WHO classification of this tumor separated it into two entities as part of a morphologic spectrum. One was termed myopericytoma (MPC) and the other as a myofibroma (MF). Then the 2013 WHO classification combined a group of similar tumors under the rubric “myopericytoma” (MPC). This class of tumors is characterized by concentric vascular proliferation of spindled cells showing differentiation towards perivascular myoid cells. These entities include solitary myofibroma, myofibromatosis, infantile hemangiopericytoma, angioleiomyoma and glomus tumor. It is still unclear if these are distinct entities, or a spectrum of the same tumor. The presented tumor is generally termed a “myofibroma.” It is the most common fibrous tumor of childhood, accounting for 20% to 25%. These lesions usually present between CTTR’s COTM September, 2013 Page 1 birth and five years of age, with a slight male preponderance. However, recent studies have shown that myofibromas may be found in any age group including children and adults. When solitary, they are usually seen on the head and neck, commonly the forehead, parotid region or scalp, and usually range from only a few millimeters in diameter up to several centimeters in diameter. They are confined to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and have a rubbery to firm touch and a white-gray to pink-purple cut surface. Clinically, they present as painless purple macules which may be mistaken for a hemangioma. Outcome is determined by disease extent at diagnosis. Individuals with fewer lesions and no visceral involvement have an excellent prognosis. These tumors may spontaneously regress in younger children, particularly those less than 2 years of age. Most cases are sporadic; however, both autosomal recessive and dominant patterns of inheritance have been described. Treatment is generally limited to complete or partial excision with a local recurrence rate of less than 10%. In cases where surgery might cause significant morbidity, chemotherapy has been used to reduce the tumor size and alleviate associated symptoms. Microscopically, myofibromas have a characteristic nodular appearance that is biphasic with areas of hyper and hypocellularity, resulting in dark and light staining. The darkly stained, hypercellular areas are centrally located and consist of whorling round to oval cells with slightly pleomorphic, hyperchromatic nuclei. There is a predominant pattern of HPC-like thin walled vessels surrounded by small spindled cells with vesicular nuclei, eosinophilic cytoplasm and indistinct cell boarders. Commonly, coagulative type necrosis, calcification and hemorrhage are present. Some tumors with extensive central necrosis mimic necrotic granulomas. The lighter staining paucicellular peripheral areas consist of plump myoid spindled cells with elongated nuclei and moderately abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. These spindle cells are arranged in short fascicles often within hyaline-myxoid stroma. Of note, the identification of peripheral myoid-appearing cells can be useful when differentiating myofibroma from other entities. In the majority of cases the histology of myofibroma is characteristic and additional studies do not need to be utilized. Immunohistochemistry can be used to distinguish it from other considerations or entities when necessary. Myofibromas stain positively for smooth muscle actin and vimentin, and to a lesser extent muscle-specific actin. In the central portion, smooth muscle actin highlights the myofibromatous pattern without reactivity in the contiguous HPC-like foci. Differential diagnosis: Infantile fibromatosis is considered in patients with multiple lesions. The individual nodules have similar features as myofibromas, except that they occur not only in the dermis, subcutis, and soft tissue, but also in muscle, bone, and internal organs. Myofibromatosis is subdivided into multifocal and generalized forms in which visceral involvement is diagnostic for generalized myofibromatosis. CTTR’s COTM September, 2013 Page 2 If only the central portion of the lesion is biopsied, various sarcomas may enter the differential diagnosis. Extensive vascular proliferation and necrosis would raise concern for entities such as congenital infantile fibrosarcoma, solitary fibrous tumor, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor, or other sarcomas. In general, immunostains that will be helpful include S-100, CD99 and cytokeratins. Congenital infantile fibrosarcoma (CIFS) usually occurs during the first year of life, with some diagnosed antenatally. Clinically, infantile fibrosarcoma presents as a solitary rapidly enlarging mass, sometimes grotesque in proportion to the child's size. The superficial and deep soft tissues of the distal extremities are the primary site in nearly two-thirds of cases, with the remainder found on the trunk, head and neck. Microscopically CIFS is highly cellular and may have a storiform or herringbone pattern. The cells are predominately spindled, but have a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio with hyperchromasia, tumor necrosis, and frequent mitoses. CIFS lacks the biphasic zonal pattern and peripheral myofibroblasts seen in myofibroma. Genetic analysis can be critical for differentiation between CIFS and myofibroma. There is a known characteristic translocation t(12;15) identified in CIFS, with 40-80% being congenital. Treatment is usually complete surgical excision. However, with appropriate treatment there is a relatively good prognosis when compared to other sarcomas. This tumor has a mortality rate of less than 5%. Infantile hemangiopericytoma usually occurs within the first year of life as a solitary lesion located in the subcutis or oral cavity. Older children may have tumors within muscle or mediastinum. Microscopically, infantile hemangiopericytoma closely resembles adult HPC/SFT, but differs in that the superficial lesions are multilobulated, often with distinct intravascular and perivascular satellite nodules outside the main tumor mass. Features such as increased mitotic activity and focal necrosis generally do not indicate a poor prognosis in infantile HPC as it does with the adult form. Treatment is similar to that of myofibroma, with possible spontaneous regression or local excision. Fibrous histiocytoma shows a pronounced proliferation of polymorphous cells arranged in a storiform pattern often with a histiocytic component, multinucleated cells and iron pigment. These cells may be smooth muscle actin (SMA) positive like myofibroma, but may also express factor XIIIa and CD68. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) is composed of spindled myofibroblasts within a variable background of collagen and inflammatory cells. IMT often shows rearrangements of the 2p23 chromosomal region, involving the ALK gene, and thus often stains for ALK-1, and lacks an HPC-like pattern. CTTR’s COTM September, 2013 Page 3 Suggested Reading: 1. Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Enzinger & Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby-Elsevier, 2008:264-269. 2. Stocker JT, Dehner LP. Pediatric Pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott WilliamsWilkins 2011:1052-1056, 1072. 3. Solitary, multifocal and generalized myofibromas: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features of 114 cases. Oudijk, Lindsey; den Bakker, Michael A; Hop, Wim C J; Cohen, Marta; Charles, Adrian K; Alaggio, Rita; Coffin, Cheryl M; de Krijger, Ronald R. Histopathology. May2012, Vol. 60 Issue 6B, pE1-E11. 4. Myofibroma of the cheek: A case report. Kassenoff, Tali L.; Tabaee, Abtin; Kacker, Ashutosh. ENT: Ear, Nose & Throat J. Jun2004, Vol. 83 Issue 6, p404-407. 5. Myopericytoma: a unifying term for a spectrum of tumours that show overlapping features with myofibroma. A review of 14 cases. Dray, M. S.; McCarthy, S. W.; Palmer, A. A.; Bonar, S. F.; Stalley, P. D.; Marjoniemi, V.; Millar, E.; Scolyer, R. A J Clin Pathol. Jan2006, Vol. 59 Issue 1, p67-73. 6. The Spectrum of Pediatric Fibroblastic and Myofibroblastic Tumors. Hicks, John; Mierau, Gary. Ultrastructural Pathol. Sep-Dec2004, Vol. 28 Issue 5/6, p265-281. 7. Malignant myopericytoma: expanding the spectrum of tumours with myopericytic differentiation. McMenamin, M E; Fletcher, C D M. Histopathology. Nov 2002, Vol. 41 Issue 5, p450-460. 8. Myopericytoma: A Pleural-Based Spindle Cell Neoplasm Off the Beaten Path. Edgecombe, Allison; Peterson, Rebecca A.; Shamji, Farid M.; Commons, Susan; Sekhon, Harman; Gomes, Marcio M. Int J Surg Pathol. 04/01/2011, Vol. 19 Issue 2, p247-251. 9. Solitary fibrous tumour and haemangiopericytoma: evolution of a concept. Guillou, L. Histopathology. Jan2006, Vol. 48 Issue 1, p63-74. Gengler, C.; 10. Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, eds. Myofibroma and Myopericytoma. In: WHO Classification of Tumors of Soft Tissues and Bone. Lyon: IARC Press 2013:89-90, 118-120. CTTR’s COTM September, 2013 Page 4