The University of Sheffield: PowerPoint template

advertisement

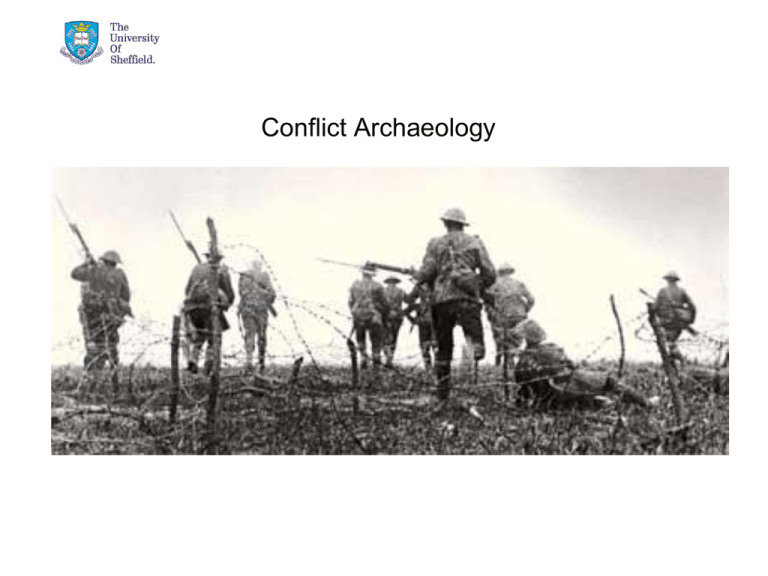

Conflict Archaeology To Discover And Understand. 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Some reasons for doing conflict archaeology The systematic study of battlefield sites can establish a close approximation of exactly what took place at that particular site. The residues of conflict , e.g. skeletal material in mass graves – can serve as a powerful tool to prevent the glorification of wars and conflict. Physical evidence recovered by archaeology can expose distortions of the truth or the use of state propaganda. Survey and assessment can document sites and provide management strategies for the long term preservation of significant these cultural resources 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield What has been studied? • Fortifications from ancient forts and medieval castles to nuclear bunkers • Battlefields of all periods and of the two types siege and transitory • Mass graves • Ship wrecks and plane crash sites • Prisoner of war camps • Cold War surveillance sites and nuclear weapon testing sites • Peace Camps 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Ground Zero after 9/11 • The destruction of the twin towers and US response coalesced around the archaeological concerns of conservation, garbage, classification, composition, and decomposition. • Archaeology is ever more clearly a way of negotiating loss due to the affective power of the material trace recognisable as ‘haunting’ or ‘enchantment’ and excess behaviour Shanks, Platt, Rathje (2004) The Perfume of garbage: modernity and the archaeological. MODERNISM/modernity 11 (1): 61-83 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield The first global industrialized conflict… Participants in World War I - Allies in green - Central Powers in orange - neutral in grey 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Dynastic alliances among ruling elites + industrialized economies + new technologies + nationalism = warfare and destruction on an unprecedented scale What made WW I so different was the long-term impact of the Industrial Revolution, with its accompanying political and social changes. - this was the first mass global war of the industrialised age, a demonstration of the prodigious strength, resilience and killing power of modern states. - the war was fought at a high point of patriotism and belief in the existing social hierarchy; beliefs that the war itself helped destroy, and that the modern world finds very hard to understand. 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Military aspects of WWI WW I is often characterized as a protracted stalemate of trench warfare along the Western Front, embodied within a system of opposing manned trenches and fortifications separated by a "No man's land" 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield The Western Front 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield - but WWI also included much fighting at sea - the first fighting in and out of the air - and the first use of tanks 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Trench Warfare 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield The scale of the destruction that was unleashed shocked contemporary observers; whole landscapes were obliterated 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield And changed the nature of warfare and the human condition 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield The Dead Poets Rupert Brooke Sub-Lieutenant Born: 1887 Died: 1915 Aged: 28 years Wilfred Owen Lieutenant Born: 1893 Died: 1918 (one week before the Armistice) Aged : 25 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Siegfried Sassoon Second Lieutenant Born: 1886 Died: 1967 Aged: 81 Casualties: each flag = 100,000 dead (skulls are civilian dead) 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Political implications WW I created a decisive break with the old world order that had emerged after the Napoleonic Wars in continental Europe Three European land empires were shattered and subsequently dismembered to varying degrees: - the German, - the Austro-Hungarian - the Russian Three European imperial dynasties also fell - the Hohenzollern - the Habsburgh - the Romanov In addition, the Ottoman Empire fell in the Balkans and the Middle East 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield The war to end all wars? - more than 9 million soldiers died on the various battlefields, and nearly as many more died in the participating countries' home fronts on account of food shortages, civil wars, and internal conflicts - in World War I, only some 5% of the casualties (directly caused by the war) were civilian - in World War II, this figure approached 50%. 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Can WWI be studied archaeologically? Nicholas Saunders University of Bristol ‘Archaeology and war have an enduring and ambiguous relationship – both create in the very act of destroying’ 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Nicholas Saunders ‘Great War archaeology is a complex endeavour. In one sense, it is a kind of industrial archaeology, whose strata are saturated with mass-produced artefacts of the 20th century – an overwhelming sea of materiality that seems to mock the archaeologist’s quest for meaningful patternings of objects. In another sense, it is historical archaeology, informed by a wealth of written documents on every conceivable aspect of the conflict, from trench life to global military strategy, from the personal meanings of memorabilia to the international consequences of its aftermath. It is also social archaeology, public archaeology, and anthropological archaeology….’ 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Saunders identifies four phases in the development of WWI archaeology 1. 1914-1918 much archaeology unearthed by all the trench digging and hybrid layers created 2. 1919-1990 re-colonisation of landscapes, creation of cemeteries, some digging in France and Belgium, but little more than amateur looting to retrieve objects 3. 1990-2001 creation of battlefield archaeology amateur societies such as ‘The Diggers’ active in Belgian Flanders; in France British teams working on sites 4. 2002-present professionalisation of Great War archaeology in Belgium, and the advent of television archaeology in France and Belgium 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield The Western Front is a multi-vocal landscape: An industrialized slaughter house, a vast tomb for Missing 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield The - a landscape of memorialization for pilgrimage Thiepval Memorial, to the missing The Somme 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield -a location for archaeological Investigation Cross Roads site, near Ypres, investigated by the Department of First World War Archaeology, supported by the Belgian Government 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Cross Roads site Passcendaele battlefield of July and August 1917 excavated ahead of new A19 motorway 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Cross Roads site: Remains of a British soldier 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Cross Roads site Equipment and shoulder badge, Royal Sussex Regiment 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield The ‘Grimsby Chums’ Mass grave of 24 British soldiers from the Lincolnshire Regiment, excavated at Le Point du Jour, outside Arras, in 2001 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield -a landscape for cultural heritage development and tourism French Ossuary and cemetery at Douaumont, Verdun Ossuary contains remains of 130,000 French & German soldiers 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield - A multi-ethnic and multi-faith war Troops from Africa, India, Australia, New Zealand, China, the Caribbean, and the Americas fought in the Allied armies in the Western Front, and other theatres of war 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield The forging of modern national consciousness: Canadian WWI poster 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield In Flanders Fields by John McCrae In Flanders fields the poppies blow Between the crosses, row on row, That mark our place; and in the sky The larks, still bravely singing, fly Scarce heard amid the guns below. We are the Dead. Short days ago We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow, Loved and were loved, and now we lie In Flanders fields. Take up our quarrel with the foe: To you from failing hands we throw The torch; be yours to hold it high. If ye break faith with us who die We shall not sleep, though poppies grow In Flanders fields. On 2 May, 1915, in the second week of fighting during the Second Battle of Ypres Lieutenant Alexis Helmer was killed by a German artillery shell. He was a friend of the Canadian military doctor Major John McCrae. It is believed that John McCrae began the draft for his famous poem 'In Flanders Fields' that evening. 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Canadians at Vimy Ridge 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Canadians at Vimy Ridge 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Canadians at Vimy Ridge Female figure representing Canada at Vimy Ridge 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield -webs of meaning and materiality that link communities around the world The Cenotaph. Whitehall. London 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Royal Artillery Memorial, Hyde Park Prior to WWI military memorials usually celebrated the victories of great men, e.g. Nelson's Column The losses of the 1914-18 war marked a turning point in memorial design, as the sacrifice of ordinary individuals began to be commemorated. 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Trench Art – a personal and creative response to the horror of modern war 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield Finally, when re-enactments of past conflicts are becoming common place, and more and more people are dressing up often with scant regard for truth and or morality - archaeologists need to work hard to establish factual accounts of conflict that prevent the past from being misused in the present. 08/04/2015 © The University of Sheffield