Family Conference OSCE - Association for Surgical Education

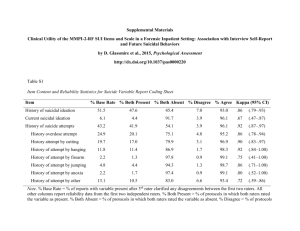

advertisement

Evaluating the Reliability and Validity of the Family Conference OSCE Across Multiple Training Sites Jeffrey G. Chipman MD, Constance C. Schmitz PhD, Travis P. Webb MD, Mohsen Shabahang MD PhD, Stephanie F. Donnelly MD, Joan M. VanCamp MD, and Amy L. Waer MD University of Minnesota, Department of Surgery Funded by the Association for Surgical Education Center for Excellence in Surgical Education, Research & Training (CESERT) Surgical Education Research Fellowship (SERF) Introduction ACGME Outcome Project – Professionalism – Interpersonal & Communication skills Need test with validated measures Professionalism & Communication More important than clinical skills in the ICU Crit Care Clin 20:363-80, 2004 – Communication – Accessibility – Continuity 1 out of 5 deaths in the US occurs in an ICU Crit Care Med 32(3):638, 2004 < 5% of ICU patients can communicate when end-of-life decisions are made Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care. Med. 155:15-20, 1997 Family Conference OSCE Two 20-minute encounters (cases) – End-of-life – Disclosure of a complication Literature-based rating tools Trained family actors and raters Ratings by family, clinicians, self Debriefing, video Chipman et al. J Surg Ed, 64(2):79-87, 2007. Family Conference OSCE Minnesota Experience High internal consistency reliability Strong inter-rater agreement Raw differences favored PGY3s over PGY1s Small numbers Chipman et al. J Surg Ed, 64(2):79-87, 2007 Schmitz et al. Crit Care Med 35(12):A122, 2007 Schmitz et al. Simulation in Health Care 3(4):224-238, 2008 Replication Study Purpose Test the feasibility of replicating the OSCE Examine generalizability of scores – Institutions – Types of raters (clinical, family, resident) Examine construct validity – PGY1s vs. PGY3s Replication Study Methods 5 institutions IRB approved at each site Training Conference (Minnesota) Site Training – Detailed case scripts – Role plays – Videos of prior “good” and “bad” performances Replication Study Methods – Learner Assessment Assessment by: – Clinical raters (MD & RN) – Family actors – Self Only family raters were blinded Rating forms sent to Minnesota Data analyzed separately for DOC, EOL Generalizabilty Theory Classical test theory considers only one type of measurement error at a time – – – – Test-retest Alternate forms Internal consistency Inter-rater agreement Generalizability theory allows for errors that occur from multiple sources – Institutions – Rater type – Family actors Provides overall summary as well as breakdown by error sources and their combinations Mushquash C & O’Connor. SPSS and SAS programs for generalizability theory analyses Behavior Research Methods 38(3):542-47, 2006 Generalizabilty Theory Summary statistics (0 to 1) – 1.0 = perfectly reliable (generalizable) assessment Relative generalizability – Stablility in relative position (rank order) Absolute generalizability – Agreement in actual score Results Feasibility N = 61 residents Implementation fidelity was achieved at each site Key factors: – Local surgeon champions – Experienced standardized patient program – On-site training (4 hrs) by PIs – Standardized materials & processes Results Internal Consistency Reliability Cronbach’s Alpha by Case Institution n Disclosure End-of-Life n = 14 items n = 14 items University of Minnesota 12 0.936 0.958 Hennepin County Med Center 7 0.867 0.935 University of Arizona 11 0.913 0.935 Mayo Clinic 13 0.934 0.949 Med College of Wisconsin 10 0.940 0.944 Scott & White, Texas A&M 8 0.924 0.957 Results Generalizability Relative G Coefficient Absolute G Coefficient End-of-life (n=61) 0.890 0.557 Disclosure 0.716 0.498 Case (n=61) The relative G-coefficients we obtained suggest the exam results can be used for formative or summative classroom assessment. The absolute G-coefficients suggest we wouldn’t want to set a passing score for the exam. Downing. Reliability: On the reproducibility of assessment data Med Educ 38:19009-1010, 2004 Results Construct Validity MANOVA Disclosure 80.0 76.7 76.0 75.0 70.0 End-of-Life 76.5 73.7 70.9 p = 0.44 72.9 68.0 65.0 62.8 60.0 p = 0.41 Family Raters Clinical Raters 55.0 50.0 PGY 1 PGY 3 PGY 1 PGY 3 Between subjects effect (PGY 1 vs. PGY 3) was not significant (p = 0.66 DOC, p = .0.26 EOL). Study Qualifications Only family members were blinded – Clinician and family ratings were significantly correlated on EOL & DOC Nested vs. fully crossed design Conclusions Family Conference OSCE Feasible at multiple sites Generalizeable Scores – Useful for formative, summative feedback – Raters were greatest source of error variance Did not demonstrate construct validity – Questions the assumption that PGY-3 residents are inherently better than PGY-1 residents, particularly in communication Study Partners Lurcat Group Amy Waer, MD – University of Arizona Travis Webb, MD – Medical College of Wisconsin Joan Van Camp, MD – Hennepin County Medical Center Mohsen Shabahang, MD, PhD – Scott & White Clinic, Texas A&M Stephanie Donnelly MD – Mayo Clinic Rochester Connie Schmitz, PhD – University of Minnesota Acknowledgments Jane Miller, PhD, and Ann Wohl, University of Minnesota IERC (Inter-professional Education Resource Center) Michael G. Luxenberg, PhD, and Matt Christenson, Professional Data Analysts, Inc., Minneapolis, Minnesota