Intra-abdominal Hypertension - Focus on Respiratory Care & Sleep

advertisement

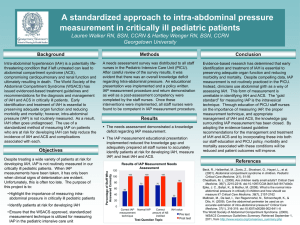

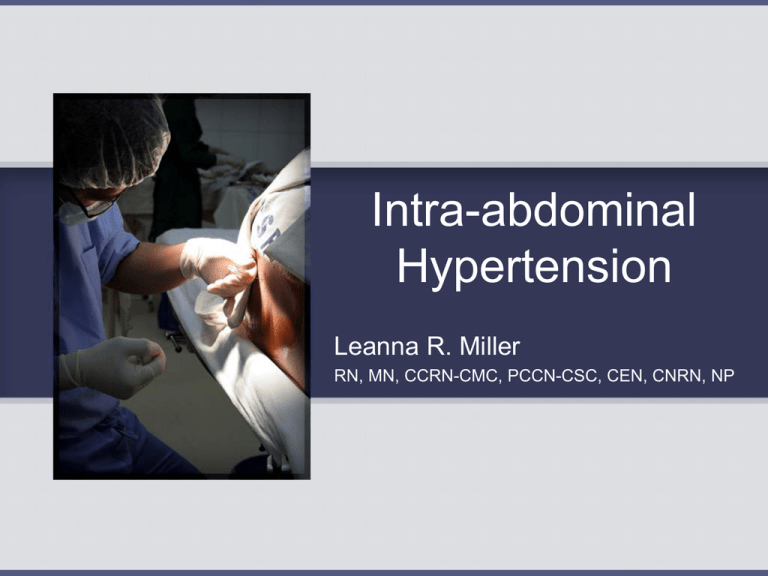

Intra-abdominal Hypertension Leanna R. Miller RN, MN, CCRN-CMC, PCCN-CSC, CEN, CNRN, NP Definitions WCACS, Antwerp Belgium 2007 • Intra-abdominal Pressure (IAP): Intrinsic pressure within the abdominal cavity • Intra-abdominal Hypertension (IAH): An IAP > 12 mm Hg (often causing occult ischemia) without obvious organ failure • Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (ACS): IAH with at least one overt organ failing Types of IAH /ACS WCACS, Antwerp Belgium 2007 • Primary – Injury/disease of abdominopelvic region, “surgical” • Secondary – Sepsis, capillary leak, burns, “medical” • Recurrent – ACS develops despite surgical intervention Physiologic Insult/Critical Illness Ischemia Inflammatory response Fluid resuscitation Capillary leak Tissue Edema (Including bowel wall and mesentery) Intra-abdominal hypertension Intra-abdominal Hypertension Compartment syndrome occurs when the pressure within a closed anatomic space increases to the point where vascular tissue is compromised with subsequent loss of tissue viability and function. This can occur within any closed body cavity. Intra-abdominal Hypertension Increased IAP leads to decreased mesenteric blood flow (MBF) and to bacterial translocation (BT), which may contribute to later septic complications and organ failure. Intra-abdominal Hypertension • IAH provokes the release of proinflammatory cytokines which may serve as a second insult for the induction of MOF. • production of interleukin-1 (IL-1 beta), interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor (TNF-) Intra-abdominal Hypertension • Symptomatic organ dysfunction that results from increased intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) • Increased IAP is an under-recognized source of morbidity and mortality. • 1-day point-prevalence observational trial conducted in 13 medical ICUs of six countries with 97 patients, 8% had IAP > 20mmHg.1 • The incidence of ACS in trauma patients is estimated to be between 2 and 9 percent.2 1Crit Care Med 2005; 33:315. 2Am J Surg 2002; 184:538. Intra-abdominal Hypertension Etiology • massive volume resuscitation is the leading cause of ACS. • inflammatory states with capillary leak, fluid sequestration, inadequate tissue perfusion, and lactic acidosis can develop ACS. • gastric overdistention following endoscopy has resulted in ACS. Intra-abdominal Hypertension • trauma (blunt or open), as a result of the accumulation of blood, fluid or edema. • gastrointestinal hemorrhage can also lead to increased pressure in the abdominal compartment as ischemic cells swell or fluids collect. • pancreatitis • pneumoperitoneum Intra-abdominal Hypertension • syndrome may follow a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm • intra-abdominal infection • coagulopathies with abdominal bleeding • cirrhosis • profound hypothermia Intra-abdominal Hypertension • massive intra-abdominal retroperitoneal hemorrhage • severe gut edema • intestinal obstruction • ascites under pressure • neoplasm Intra-abdominal Hypertension • Patients who have undergone long surgical procedures with intraoperative hypotension and large fluid requirements are at significant risk, particularly if the abdomen has been closed under pressure in the OR. • External pressure from circumferential burns about the abdomen, application of military anti-shock trousers (MAST), or even tight abdominal restraint devices can cause tension within the abdomen due to external forces and result in ACS Intra-abdominal Hypertension Recently, awareness of the ACS has increased for 2 primary reasons. • First, the increased use of laparoscopy among general surgeons has brought with it an appreciation of IAP as a readily quantifiable entity. • Second, the more frequent use of planned repeat laparotomy for trauma has allowed both surgeon and intensivist to appreciate the beneficial effects of abdominal decompression upon removal of packing or evacuation of hematoma. Intra-abdominal Hypertension • Interpreting IAP 0 – 5 mm Hg 6 – 11 mm Hg 12 – 15 mm Hg 16 – 20 mm Hg 21 – 15 mm Hg > 25 mm Hg normal minimal elevation common finding in ICU Grade I Grade II Grade III – high risk for ACS Abdominal Compartment Syndrome Intra-abdominal Hypertension Abdominal Compartment Syndrome “. . . . . . .the end result of a progressive, unchecked increase in intra-abdominal pressure from a myriad of disorders that eventually leads to multiple organ dysfunction” Intra-abdominal Hypertension Grading System for ACS Grade Bladder pressure (cm water) Indication of surgical decompression I 10-15 No evidence of ACS II 15-25 Based on patient condition III 25-35 Decompression indicated IV >35 Immediate decompression Elevated IAP Intra-abdominal Hypertension • • • IAH may develop rapidly Monitor the trend: rising IAP or sustained IAH poor prognosis Recommendation: Measure IAP at each Urine Output determination Physiologic Sequelae The Pathophysiology of IAH IAP VASCULAR COMPRESSION RVP IVC Flow DIAPHRAGMATIC ELEVATION Cardiac compression DIRECT ORGAN COMPRESSION Intrathoracic pressure Cardiac preloadCardiac contractility Systemic afterload PV pressure CARDIAC OUTPUT Renal Vascular Resistance RENAL FAILURE Splanchnic Vascular Resistance ABDOMINAL WALL ISCHAEMIA/OEDEMA RESPIRATORY FAILURE ICP SPLANCHNIC ISCHAEMIA Effects on CVS • As intra-abdominal pressure increases above 10 mmHg, cardiac output declines, despite normal arterial pressures. • Additionally, whole body oxygen consumption, pH, and PO2 decrease. • Intra-abdominal hypertension affects cardiac function by pushing the hemi-diaphragms upward, thus transmitting the abdominal pressure to the heart and its vessels. • This decreases preload and increases afterload on the left ventricle and at the same time creates a hemodynamic picture of low cardiac output and high filling pressures 35 3.5 3 2.5 25 2 1.5 15 1 0.5 Wedge pressure (mmHg) Cardiac index (L/min/m 2) 4 Cardiac index Wedge pressure 0 0 5 10 15 20 25 IAP (mmHg) above baseline) Effect of increased intra-abdominal pressure on cardiac index and pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (J Trauma 1995; 39:1071-1075) Physiologic Sequelae Cardiac: • Increased intra-abdominal pressures cause: – Compression of vena cava with reduced venous return – Elevated intra-thoracic pressure with multiple negative cardiac effects • Result: – – – – – Decreased cardiac output, increased SVR Increased cardiac workload Decreased tissue perfusion Misleading elevations of CVP and PAOP Cardiac insufficiency; cardiac arrest Effects on Pulmonary System • most commonly noted effects of IAH on the pulmonary system are: – elevated peak inspiratory pressures – decreases in PaO2 – increases in PaCo2 • requires the use of complete ventilatory support to maintain adequate oxygenation and ventilation. • positive end-expiratory pressure has been shown to exacerbate the cardiac and respiratory consequences of IAH . Physiologic Sequelae Pulmonary: • Increased intra-abdominal pressures causes: – Elevated diaphragm, reduced lung volumes & alveolar inflation, stiff thoracic cage, increased interstitial fluid • Result: – Elevated intrathoracic pressure (which further reduces venous return to heart, exacerbating cardiac problems) – Increased peak pressures, reduced tidal volumes – Barotrauma - atelectasis, hypoxia, hypercarbia – ARDS (indirect - extrapulmonary) Pulmonary Effects of IAH • mechanical ventilation often necessary • high peak airway pressures barotrauma • high PEEP often required further compromising CO Pulmonary Effects of IAH Pressure on the IVC predisposes to venous stasis and increased risk of thromboembolism IAH and Splanchnic Flow • increases in IAP have adverse effect on splanchnic flow • >15mmHg SM blood flow • marked reduction in hepatic artery and portal venous blood flow • leads to mucosal acidosis and edema IAH and Splanchnic Flow Splanchnic hypoperfusion Hepatic ischemia Gut mucosal acidosis IAH Bowel edema Coagulopathy hypothermia Unrelieved acidosis Intraabdominal bleeding Free oxygen radicals Distant organ damage ACS Intra-abdominal Hypertension • measured mucosal and intestinal blood flow and intramucosal pH (pHi) and found that mesenteric and mucosal blood flow decreased when IAP reached 20 mmHg, with intestinal mucosal flow declining to 61% of baseline • At an IAP of 40 mmHg, intestinal flow decreased to 28% of baseline • Intestinal mucosa showed signs of a severe degree of acidosis, measured by tonometer. These changes in splanchnic blood flow occurred despite maintenance of baseline cardiac output with volume loading Intra-abdominal Hypertension • blood flow to virtually every abdominal organ decreased significantly. The only exception was the adrenal gland; the reason this organ is not affected is unknown ? Physiologic Sequelae Gastrointestinal: • Increased intra-abdominal pressures causes: – Compression/Congestion of mesenteric veins and capillaries – Reduced cardiac output to the gut • Result: – Decreased gut perfusion, increased gut edema and leak – Ischemia, necrosis – Bacterial translocation – Development and perpetuation of SIRS – Further increases in intra-abdominal pressure Effects on Renal System • decreased renal plasma flow, glomerular filtration rate, and glucose reabsorption. • oliguria also occurs, with anuria noted in animal models when IAP reaches 30 mmHg • effects occur without significant decreases in blood pressure (mechanical, ↑ PVR, compression of renal vein→ outflow obstruction→ ↑ intraparenchymal pressure → shunting of blood from renal cortex) Effects on Renal System • improvement of cardiac output does not improve renal function, nor do renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate improve. • the placement of ureteral stents failed to improve renal function. • improvement in renal function occurred only after abdominal decompression Intra-abdominal Hypertension • These findings suggest that the effects of IAH on renal function are related to compression of the renal parenchyma itself and to compression of renal vasculature and are not related to decreased cardiac output. • other mechanisms proposed include shunting of blood away from the renal cortex into the medulla, decreased renal arterial flow with a concomitant increase in renal vascular resistance, and the presence of high levels of renin, aldosterone, and antidiuretic hormones. Physiologic Sequelae Renal: • Elevated intra-abdominal pressure causes: – Compression of renal veins, parenchyma – Reduced cardiac output to kidneys • Result: – – – – Reduced blood flow to kidney Renal congestion and edema Decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) Renal failure, oliguria/anuria • Mortality of renal failure in ICU is over 50% DO NOT WAIT for this to occur! Effects on CNS • The rise in intra-abdominal pressure, intrathoracic pressure leads to a rise in central venous pressure which prevents adequate venous drainage from the brain, leading to a rise in intracranial pressure and worsening of intracerebral edema. Intracranial Derangements • IAH associated with – ICP – CPP cerebral ischemia • ?Why? • may be due to impairment of cerebral venous outflow Central Nervous System Implications ICP CPP retinal capillaries rupture Valsalva retinopathy Sudden decrease of central vision Intra-abdominal Hypertension • increased intrathoracic pressure causing increased resistance to cerebral venous return associated with IAH( ?pseudotumor cerebri). • Volume expansion further increased ICP. Cerebral perfusion pressure declined as ICP increased and cardiac output declined. • Only abdominal decompression reversed effects of IAH. • The exact level of IAH that results in elevated ICP and decreased CPP in the brain injured patient is unknown Physiologic Sequelae Neuro: • Elevated intra-abdominal pressure causes: – Increases in intrathoracic pressure – Increases in superior vena cava (SVC) pressure with reduction in drainage of SVC into the thorax • Result: – Increased central venous pressure and IJ pressure – Increased intracranial pressure – Decreased cerebral perfusion pressure – Cerebral edema, brain anoxia, brain injury Multisystem Organ Failure Intra-abdominal Pressure Capillary leak Mucosal Breakdown Decreased O2 delivery Free radical formation (Multi-System Organ Failure) Anaerobic metabolism Bacterial translocation Acidosis IAH / ACS Affects Outcome Points: • IAH and ACS are common entities in the critical care environment (including your own). • IAH and ACS increase morbidity, mortality and ICU length of stay………… However: • Clinical signs of IAH are unreliable and only show up late in the clinical course …..SO • Early monitoring (TRENDING) & detection of IAH with early intervention is needed to reduce these complications. Measurement of IAP Diagnosis of ACS • Intra – abdominal pressure 25 mmHg or 30 cmH20/ urine • One or more of the following signs of clinical deterioration – ↑ pulmonary pressures – ↓ cardiac output – ↓ urinary output – acidosis – hypoxia – hypotension • abdominal decompression results in clinical improvement Indications for IAP Monitoring • • • postoperative (abdominal surgery) ventilated pts with other organ failure patients with signs of ACS: – oliguria, hypoxia, hypotension, acidosis, mesenteric ischemia, ileus, elevated ICP. • • high cumulative fluid balance abdominal packing Intra-abdominal Hypertension Abdominal compartment pressure monitoring is done to help recognize life threatening elevations in pressure before ischemia or infarction of the abdominal organs occurs. When a patient exhibits a distended and taut abdomen, the measurement of abdominal compartment pressure can provide direction regarding the need for decompressive surgery Measurement of IAP Direct Monitoring • The most direct, accurate way to measure intraabdominal pressure is through an intraperitoneal catheter attached to a water manometer or pressure transducer, the preferred method in most experimental studies of IAH. • Its use in the clinical situation is limited by the potential complications, specifically the risk of peritoneal contamination or bowel perforation. • Abdominal pressure measured during laparoscopy is another example of direct measurement Indirect Monitoring • Intraabdominal pressure may be indirectly measured by measuring pressure within certain abdominal organs. • The first indirect method described involves placement of transfemoral catheters into the inferior vena cava .The associated risks of this procedure include infection and thrombus formation. • measurement of gastric pressure through gastrostomy or nasogastric tubes • esophageal stethoscope catheter • urinary bladder pressure measurement Bladder Pressure Monitoring • at intravesical volumes less than 100 mL, the bladder acts as a passive reservoir, accurately reflecting intra-abdominal pressure within a range of 5 to 70 mmHg • when bladder volumes exceed 100 mL, the intrinsic contraction of the bladder wall causes bladder pressure to increase. Intra-abdominal Hypertension • the basic technique of bladder pressure measurement is not complicated. Fifty to 100 mL of sterile saline is injected into the bladder through a Foley catheter while the tubing to the drainage bag is clamped distal to the aspiration port • the clamp is then opened to allow fluid to fill the tubing proximal to the clamp and the tubing is then reclamped “Home Made” Pressure Monitoring Home-made assembly: – – – – Transducer 2 stopcocks 1 60 ml syringe, 1 tubing with saline bag spike/luer connector – 1 tubing with luer both ends – 1 needle / angiocath – Clamp for Foley Assembled sterilely in proper fashion Intra-abdominal Hypertension Intra-abdominal Hypertension “One Step” Infusion of saline into bladder: 1. Aspirate 20 ml saline into the syringe. 2. Compress the syringe to infuse the saline. 3. Read the IAP 4. Repeat as needed Measure Drain That’s all – no valves or clamps or easily made errors Intra-Abdominal Pressure Monitoring • How much fluid should be infused into the bladder? – The minimal amount of fluid required to obtain a reliable IAP measurement. – Too much fluid leads to bladder over distention and bladder wall compliance issues – Currently it appears that one never needs more than 25 ml in an adult, less (10-20 mL) is probably adequate Intra-abdominal Hypertension • patient positioning affects the accuracy of bladder pressure measurements. • monitoring should occur with the patient supine so that the weight of the abdominal contents pressing on the bladder does not falsely elevate the reading. • if patient is unable to remain supine, the position at which the first measurement is taken should be noted and subsequent measurements taken with the patient in that position • although the individual reading may be inaccurate, trends in abdominal pressure can still be assessed Intra-abdominal Hypertension • Unfortunately, this procedure requires that the closed urinary drainage system be opened each time pressure is measured, placing the patient at increased risk of infection. • Strict aseptic technique is essential. A sterile towel should be placed under the Foley catheter to maintain sterility . Intra-abdominal Hypertension In patients with a neurogenic bladder or in those having a small contracted bladder (e.g., after radiotherapy), measurements may be inaccurate. Management of IAH and ACS Abdominal Perfusion Pressure (APP) APP = MAP – IAP • Abdominal perfusion pressure reflects actual gut perfusion better than IAP alone • Optimizing APP to > 60 mm Hg should probably be primary endpoint IAP Monitoring Protocol IAP monitoring Q1-2 hours for first 12 hours IAP IAP 12 to 15 IAP 15-20 mm Hg IAP >20 mm Hg consistently mm Hg with no evidence OR <12 mm Hg of organ dysfunction/ APP< 50-60 mm Hg? ischemia (ACS) Plus evidence of Optimize Abdominal organ dysfunction/ perfusion pressure ischemia (ACS) •Careful fluid management •Vasopressors Reduce IAP measurements Consider Medical Management to Q4-6 hours • Sedation/Neuromuscular blockade for 24 hours • Paracentesis of free fluid “Second Hit” pt. develops new indication for IAP monitoring IAP remains <12 mm Hg discontinue monitoring •Other options Surgical -Gastric suction, cathartics Decompression -Rectal tube/enemas -Continuous filtration -Colloids Intra-abdominal Hypertension Pressure Grade Management 10-15 mm Hg I maintain normovolemia 16-25 mmHg II 26-35 mmHg III hypervolemic resuscitation decompression > 35 mm Hg IV decompression and re-exploration Prevention of ACS Most commonly used open Current opinion does abdomen techniques not support liberal include use of an open abdomen technique • bogota bag (25%) to prevent ACS • absorbable mesh (17%) • prolene mesh (14%) • silastic mesh (7%) • miscellaneous (28%) The Journal of Trauma, Infection and Critical Care 1999;47 :509-511 Intra-abdominal Hypertension • an alternative technique is the 'vacuum-pack' technique. Here the 3 liter bag is opened and placed into the abdomen to protect the gut contents, under the sheath. • two large caliber suction drains are placed over this, and a large adherent steridrape placed over the whole abdomen. • suction catheters are connected to highdisplacement suction to provide control of fluid losses and create the 'vacuum-pack' effect Operative Decompression Vacuum-assisted temporary abdominal closure device: A thin plastic sheet, a sterile towel, closed suction drains, and a large adherent operative drape. This dressing system permits increases in intra-abdominal volume, without a dramatic elevation in IAP. Decompressive Laparotomy • Delay in abdominal decompression may lead to intestinal ischemia • Decompress early! Case Presentations Case: Septic Patient 45 y.o. female presenting with septic syndrome • Treatment: Culture, Antibiotics, Fluids, Vasopressors • 24 hours into therapy develops worsening hypotension, oliguria, hypoxemia, hypercarbia. PIP rises from 20 to 40 cm H2O • IAP = 26 mm Hg decompressive laparotomy • Immediate resolution of renal, pulmonary and hemodynamic compromise • 7 days later abdomen closed. • Alive and well now. Case: Dyspnea in ER 67 y.o. female presenting to ER with pleurisy, dyspnea • Hypotensive, agitated, H&P suggest liver disease • IVF resuscitation, intubation, sedation • Worsened over next 4-6 hours - Difficult to ventilate, hypoxic/hypercarbic, hypotension, no UOP. • IAP = 45 mm Hg, abdominal ultrasound showed tense ascites paracentesis of 4500 cc fluid (IAP = 14) • Immediate resolution of renal, pulmonary and hemodynamic compromise. • Pathology shows malignant effusion – pancreatic CA. • Care withdrawn at later time and allowed to expire. Etzion, Am J EM 2004 Case: Aspiration Patient 77 y.o. male aspirated on general medicine floor. Transferred to MICU & intubated; hypotensive. • 10 liters IVF overnight, Levophed 40 mcg/min. • Anuric (35 ml urine in 8 hours). • IAP = 31 mm Hg. KUB – massively distended small and large bowel. U/S shows no free ascitic fluid. • Surgeon consulted for possible decompressive surgery • Rx: NGT, Rectal Tube, oral cathartics • 1 hour later: IAP 12 mm Hg, UOP 210 ml, norepinephrine discontinued. Cheatham, WSACS 2006 Case Points • Trauma is not required for ACS to develop: – Intra-abdominal hypertension and ACS occur in many settings (PICU, MICU, SICU, CVICU, NCC, OR, ER) • IAP measurements are clinically useful: Help to determine if IAH is contributing to organ dysfunction (i.e. useful if normal or abnormal) Case Points • “Spot” IAP check results in delayed diagnosis: – Waiting for clinically obvious ACS to develop before checking IAP changes urgent problem to emergent one. • IAP monitoring will allow early detection and early intervention for IAH before ACS develops. WSACS Guidelines Cheatham, ICM 2006 Intra-abdominal Hypertension WSACS recommendations • • Non-surgical treatment options: – paracenthesis – Gastric suctioning, enemas – Gastro/colon prokinetics – Furosemide, with or without albumin – CVVH with aggressive ultrafiltration – Sedation Surgical: Decompression Intra-abdominal Hypertension Summary • ACS is a clinical entity caused by an acute, progressive increase in IAP. • Multiple organ systems are affected, usually in a graded fashion. • The gut is the organ most sensitive to IAH. • Treatment involves expedient decompression of the abdomen. • Since this syndrome affects patients who are already physiologically compromised, a high degree of suspicion and a low threshold for checking bladder pressures are required to prevent the mortality associated with this complex problem. Final Thoughts Do NOT wait for signs of ACS to check IAP – By then the patient has one foot in the grave! – You have lost your opportunity for medical therapy Monitor ALL high risk patients early and often: – TREND IAP like a vital sign • 30-50+% of all ICU patients have some IAH and are at risk for ACS • 1 in 11 suffer full blown abdominal compartment syndrome