File

advertisement

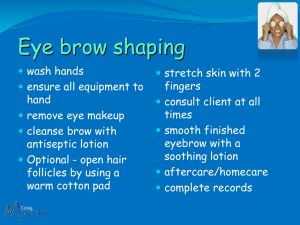

Mendoza-Denton, N. (1996). ‘Muy macha’: gender and ideology in gang girls’ discourse about makeup. Ethnos 61 (1-2): 47-64. Presented by Karen Cralli, Iliana Perea, Patrick Humphries Introduction Mendoza-Denton (1996) explores the role of power, femininity, and ethnicity in the discourse of gang girls and those discourses related to them. In particular, she explores Mexican gang girls (cholas) and their use of make-up Norteñas: identify with chicano and U.S. culture Sureñas: identify with Mexican culture The power of eyeliner A but B Many feminist scholars have identified makeup as a tool of oppression that imposes a certain femininity upon women; the cholas, however, use makeup to express a rejection of traditional femininity—that is, they challenge traditional gender roles through make-up. . Theoretical Approach Performativity of gender (Turner, 1982: Butler, 1990, 1995) Gender is socially constructed, and is the result of the “repeated stylization of the body within a rigid regulatory framework” (Butler, p.???) The cholas “do gender” through their makeup choices and clothing choices GOLDSTEIN???? BORDO??? Methods Mendoza-Denton employed sociolinguistic interviews and performed ethnographic field work for 2.5 years Developed personal relationships with the young women Worked as an academic tutor at a high school Population: high school-aged young women from Sor Juana High School in Santa Clara County, CA Sor Juana High School: Urban setting, majority of students are people of color, gang activity in the community Space and Place Mendoza-Denton does not address the issue of space, but it is fundamental to understanding chola makeup and culture Cholas use makeup to project an intimidating image that is easily identifiable at a distance (a visual warning) Chola makeup is akin to war-paint—a visible sign of willingness to fight They are defenders and protectors of their own territory, which implies the existence of a threat or a need for defense Their look rejects a mainstream sexualized femininity It is dangerous to look femininepotential (sexual) threat to women of the community “The Lexicon of Makeup” Norteñas Sureñas Eyeliner Pencil liner, followed by liquid liner Liquid liner Lipstick/Lip liner Dark red/Burgundy lipstick Brown liner (not filled in) Hair Feathered; sometimes dyed a reddish color “Vertical ponytail” straight pony tail with sides gelled down; sometimes dyed black Light-eyed girls often wear dark contacts Light-skinned girls wear dark foundation The cholas prize Physical strength and athleticism; heavier/curvy bodies are idealized—leaders are often “zaftig” (p. 58) Lexicon of Makeup, interpreted Chola use of makeup is a form of reappropriation; they use a tool of traditional feminity to reject traditional feminitymakeup is used to intimidate and establish “masculine” qualities Cholas maintain some aspects of a “traditionally feminine” look (e.g. long hair). Long hair may symbolize Mexican heritage or identity Dark foundation used to emphasize Mexican heritage, where this is a point of pride Dark foundation also used to cover bruises and hickies Eyeliner symbolizes “hardness” or willingness to fight; the longer the eyeliner, the tougher the chola Chola makeup indicates group membership; cholas can tell who is and who is not a chola by their use of makeup, and whether she is sureña or norteña. Cholas in their own words “Everybody looks at you but nobody fucks with you” (p. 57) (To Mendoza-Denton after she received a chola makeover): “You’re hard. Nobody could fuck with you, you got power. People look at you, but nobody fucks with you…I look like a dude,¿ que no?” (p. 56) “When I turn on the eyeliner, when I really put it on, you know long and shit, it makes me feel like another person, it makes me feel tough. Just wearing the eyeliner even without the clothes makes me feel brave.” (p. 57) “When I wear my eyeliner, me siento más macha, I’m ready to fight” (p. 55) Chola discourse Hard Brave Macha Looking in Dude Conclusion By using the “tools of femininity” for unintended purposes, the cholas reject traditional femininity, instead establish themselves as powerful and intimidating figures. Eyeliner length and lipstick/lipliner choice communicate willingness to fight, as well as group identification (norteña v. sureña). Criticisms/Questions/Comm ents An internet search of “chola” leads to mocking images and videos (chola halloween makeup and costume tutorials, mocking music videos and parodies). Does this imply that society rejects women’s ability to be intimidating? What necessitates or motivates the chola lifestyle? Is femininity viewed as a liability or a danger? Going to college, leaving their space/territory, thus no need for “Warrior” image Mendoza-Denton (1996) consistently refers to the cholas as “girls,” rather than “young women.” In doing so, the cholas are rendered harmless. She represents them as tough girls that grow out of gang life, with a sanitized image of what gang life can mean for the cholas (by ignoring violence, pregnancy, family tension, etc) Cholas within family context? Analysis 15 years later Questions/Comments/Critici sms Mendoza-Denton notes that as the cholas head off to college, they adopt a more traditionally feminine look. Why? Does leaving the community eliminate the need for the chola look? Does the social environment of college encourage a more “mainstream” look?