EAST 317 WEEK ELEVEN JAPANESE AESTHETICS I. Importance

advertisement

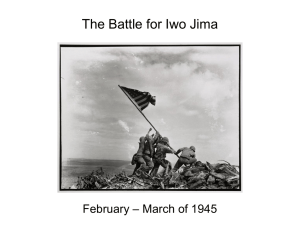

EAST 201 UNIT TEN JAPANESE AESTHETICS HISTORY OF MODERN JAPANESE ART (based on Modern Japanese Art, A Concise History: Gallery Guide to the Collection of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 2005) “ . . . modern Japanese art has evolved under the strong influence of European and American art. . . Although the Japanese people were at the mercy of the gap that existed between European culture and their own, that gap served as a stimulus for them to develop shrewdly a new culture of their own. [6] “From the beginning of the 20th century onwards, Japanese painting was divided into two categories, nihonga (Japanese-style painting) and yoga (Western-style painting). . . Nihonga is a direct extension of Japanese painting from ancient times and employs sumi ink and mineral pigments on paper or silk. Yoga refers to painting done in oil, a medium that was rapidly transplanted from Europe from the latter half of the 19th century onwards.” (7) 1. At the Launch of the Fine Arts Exhibition (Bunten) (1907) Having outgrown both worship of the West and xenophobic nationalism, the country started to explore what kind of culture it would need to acquire as a modern nation. Shimura Kanzan, Autumn among Trees (1907) Skillfully adopted Western techniques in order to modernize nihonga. Autumn among Trees depicts the trees in graded shades in order to provide Western-style perspective, which gives the overall image of depth. Hishida Shunso, Bodhisattva Genju (1907) Shunso in Bodhisattva Genju painted in a pointillist style, without employing lines. Graduating the color tones produced a sense of perspective and three-dimensionality. Wada Sanzo, South Wind (1907) South Wind, ordinary people’s life presented with compassion, as well as historical episodes that reflected the artist’s own feelings towards historical characters in ways not seen in earlier works that were detached and without subjective emotion. 2. Art in the Meiji (1868-1912) and Taisho (1912-1926) Periods–Humanism The need to make statements advocating individuality and freedom was apparently based on a new set of values that had emerged against the nationalism dominating the country since the Meiji Restoration, when it was adopted as a necessity in achieving modernization. Ogiwara Morie, Woman (1910) Woman is of monumental significance in the history of modern sculpture in that it enabled the Japanese to realize the expressive potential of sculpture. “Throughout the Meiji period, all Japanese sculpture had managed to do was to present the model faithfully. Ogiwara reached a totally new level when he succeeded in capturing human beings complete with emotions of love and agony.” (30) Hayami Gyoshu, Tea Bowl and Fruits (1921) Taisho Realism, as seen in Hayami’s Tea Bowl and Fruits, emphasized texture over spatial depth and attached great importance to the act of diligently working on precise details. Kishida Ryusei, Road Cut through a Hill (1915) Road Cut through a Hill (1915), one sees the way he tries to identify “beauty’’ in even the soil and weeds by depicting them realistically with great persistence. 3. Art of the Prewar Showa (1926-1945) Period–Artists in the Modern City “The Great Kanto Earthquake hit the Tokyo area in 1923 and the city suffered extensive destruction. The last remnants of old houses from the Edo period were wiped out, and concrete buildings started to pop in their place. The first subway line was opened, and other fundamentals of a modern city were built one after another. . . , the new urban culture blossomed in large cities, and women wearing bobbed hair and Western-style clothes, called `moga’ (modern girls), flocked to fashionable places and enjoyed the new liberated lifestyle.” Innovative trends developed under the influence of European movements such as Cubism, Futurism, Expressionism, Dadism, and Constructivism. Japanese artists began to discover the special dynamism and social contradictions of the large city. People found that life in large cities, which offered spectacles and stimulation, was coupled with the solitude of being an anonymous individual within a huge crowd. The sense of disconnectedness and the need for spiritual support grew. Murals became very popular and many cafes and department stores adorned their walls with them. Saeki Yuzo, Gas Lamp and Advertisements (1927) Hasekawa Toshiyuki, View of Shinjuki (c. 1937) 4. Art of the Prewar Showa (1926-1945) Period–Maturity of Nihonga (Japanese-style painting Only nationalistic values were approved by the government and society, so artists came to take more interest in Japanese culture and the Eastern heritage, and many adopted techniques and expressions from traditional Japanese art. Sophisticated approach to composition and colour choices was, at the same time, based on a thorough grasp of traditional painting styles from Japan and, more generally, from the East. Both Kobayashi’s Indian Corn Plants (1939) and Yasuda’s Camp at Kisegawa (1940/41), which are good examples of this style, show an excellent grasp of form and colour, while the less important details and emotional elements have been eliminated and the background is left blank. Kobayashi Kokei, Indian Corn Plants (1939) pair of screens Yasuda Yukihiko, Camp at Kisegawa (1940-/41) pair of screens 5. Art during and after the War The majority of artists were sent to the front and commissioned by the army to paint records of the war. Shimizu Toshi, Japanese Engineers’ Bridge Construction in Malaya (c.1944) After the war, artists confronted a relationship between art and society that differed from that which existed during the war. “Realism,” that is, an effort to approach the truth, was reinvestigated. Artists tried to approach human existence itself, rid of ostentation, or to uncover social contradictions. Aso’s Saburo, Red Sky (1956), represents a human being confronting the oppressive reality of the postwar era by placing one layer of paint over another as if in contention against the space of the image. “Nihonga” artists also sought a new direction. The postwar era criticized various traditions and conventions that had previously prevailed in Japan. Aso Saburo, Red Sky (1956) Under such circumstances, nihonga was also a target for reexamination. Nihonga artists responded by questioning the meaning of tradition and how a new type of nihonga could be created from it. Road (1950) by Higashiyama Kaii hints at the start of postwar nihonga, a means of projecting spirituality within a modern formal sensibility. Higashiyama Kaii, Road (1950) 6. Art in the 1950s and the 1960s The first step forward for postwar art was to part with the half-hearted attitude towards work that still persisted from before. The significance of nihonga, which was so adamant about observing tradition that it had become detached from social reality, was questioned strongly In Yokoyama’s Tower (1957). Yokoyama Misao, Tower (1957) Hamaguchi Yozo, Blue Glass (1957) mezzotint New ideas were introduced to allow the artist’s feelings to be revealed. Art was considered to be a direct confrontation between the paint and the brushwork and the artist’s body. Out of this tension came experimental expressions that went far beyond the conventions of art. Mainstream art shifted away from realism and into abstract painting. Hamaguchi Yozo’s, Blue Glass (1957) is characterized by a black background. Within the silent darkness, a vivid impression is produced through the contrast between the cold texture of the cherries visible through the blue glass and the feeling of vitality in the cherries overflowing the bowl. Beginning in the late 50's the anti-art movement began, which featured the use of waste materials to create art, with a goal to destroying the existing view of art. In 1964, this movement carried forward into guerilla events on the streets of Tokyo in attempt to disturb the order of the city that was being prepared for the Olympics. This was an age of many new forms of expression beyond the framework of conventional genres. Miki Tomio, Ear (1965) 7. Contemporary Art, the 1970s and Beyond The artist, by working his material, whether paint or plaster, aesthetically refines form and color and transfers it from the world of nature to the side of culture. However, from the late 1960s, a group of artists known as Mono-ha (Matter-school), . . . began creating a different type of work. They refrained as far as possible from processing matter and attempted to present the incident itself that occurs through the one-time encounter between nature (matter and space) and mankind. Enrokura Koji, Interference (Story-No. 18) (1991) Instead of paint and bronze, they employed natural materials such as stone, wood, soil, and sometimes fire, water, or live animals. Instead of the traditional procedures of drawing, painting, or sculpting, acts following natural force (gravity), such as laying, stacking, and leaning, came to play the key role. . . Enokura Koji’s Interference (Story-No. 18) (1991) took advantage of the physical phenomenon of paint seeping into cotton. Lee U-Fan, From Line (1977) Lee U-Fan in From Line (1977) dipped his brush in mineral pigments and pulled it downwards in a single stroke. He performed this act repeatedly until he had covered the entire canvas. SLIDE Kusama Yayoi, I Want to Live Forever (2008) is said to have experienced since childhood a peculiar vision of a pattern that proliferates to such an extent that it fills the world and the artist herself ceases to exist. The ultimate unity of the world and the self eventually became the continuing subject of Kusama’s art. The canvas is covered in minute nets and dots, of which not a single one is the same as any other.