Geison - 1995 - Private Doubts and Ethical Dilemmas Pasteur, Roux

advertisement

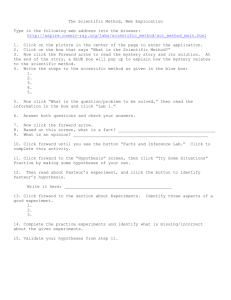

The Private Science of Louis Pasteur Gerald L. Geison Published by Princeton University Press Geison, Gerald L. The Private Science of Louis Pasteur. Course Book ed. Princeton University Press, 2014. Project MUSE. muse.jhu.edu/book/33853. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/33853 [ Access provided at 4 May 2021 20:03 GMT from Harvard Library ] nm —™ m NINE •••__ •••"~ Private Doubts and Ethical Dilemmas: Pasteur, Roux, and the Early Human Trials of Pasteur's Rabies Vaccine O NE DAY in the mid-1880s, the "independent" research of Pasteur and his leading collaborator on rabies, Emile Roux, came too close for comfort On that day, or so we are told by Pasteur's nephew and research assistant Adnen Loir, he prepared some cultures of the swine fever microbe, working as always under Pasteur's watchful eye, and carried them to a laboratory stove Since Loir's hands were filled with flasks, Pasteur opened the door of the stove for him As Loir went about his usual tasks, Pasteur noticed an unusual flask in the stove a flask of 150 cubic centimeters supplied with two tubules open to the ambient atmosphere, one above the other and so arranged as to produce a continuous stream of ordinary air inside the flask (see fig 8 3) Loir's account continues as follows In this flask a strip of rabbit spinal cord was suspended by a thread The sight of this flask, which [Pasteur] held aloft, seemed to absorb [him] so much that I did not want to disturb him After a long silence, he asked me, "Who put this flask here'" I answered that "it could only be M Roux," for "this is his rack " [Pasteurl took the flask and went down the hall He raised it above his head, and set himself to look at it in the full light of day for a long, long time Then he returned to put the flask back in its place [on Roux's rack in the stove] without saying a word ' But if Pasteur said little to Loir about Roux's unusual flask, he did immediately order the construction of a dozen similar flasks—stipulating, however, that they should differ from Roux's flask in two ways they should be much larger in volume, and they should contain caustic potash in order to DOUBTS AND ETHICAL DILEMMAS 235 dry the air flowing through them By adding caustic potash, which Roux had not done, Pasteur hoped to prevent the spinal strip from putrefying m ordinary air Under those conditions, any attenuation of the rabies virus m the spinal strip could be ascribed to the effect of "allowing [atmospheric] oxygen time to attenuate the virus"—in keeping with Pasteur's preference for oxygen-attenuated vaccines 2 The very next day Pasteur began suspending strips of rabbit spinal cord in his new desiccating flasks, which he let stand at ordinary room temperature instead of depositing them in the stove, as Roux had done That afternoon, Roux noticed three of these new flasks sitting on a table in the laboratory He sent for Loir "Who put those three flasks there," he asked me while pointing to the table "M Pasteur," I answered "He went to the stove'" [asked Roux] "Yes" [I replied] Without saying another word, Roux put on his hat, went down the stairs, and left by the door on the rue d'Ulm, slamming it shut as he [always] did when angry3 According to Loir, Roux never said a word to Pasteur about this incident But thereafter, he claimed, Roux came to the laboratory only at night, when he knew he would not cross paths with Pasteur And from that moment, Loir continued, rabies became a "dead letter" for Roux 4 Here, as often elsewhere in his reminiscences, Loir provides no exact date—not even a year—for this anecdote But Loir surely did not intend his last sentence to be taken literally For Roux did not become permanently estranged from the Pastonan rabies project Elsewhere, Loir himself describes Roux's return to Pasteur's laboratory and his crucial contributions to its work on rabies Even so, Loir's anecdote is a striking illustration of a more general theme the tension between Pasteur and Roux The exact nature of the relationship between them has long been an object of discussion and speculation To judge from the most credible accounts, this was not a simple case of an affectionate disciple working happily under the master's yoke 5 From time to time in the rest of this chapter, I will suggest that at least some of the discord between Pasteur and Roux over rabies can be traced to differences in their professional formation and orientation Here Pasteur as life-long experimental scientist is contrasted with Roux as a former medical man who never forgot the lessons of his brief career in clinical medicine and who earned part of that professional ethos with him when he joined the Pastonan team, especially when it came to the application of rabies vaccines to human cases Admittedly, Pasteur and Roux somehow managed to put aside, or paper over, their differences when push came to shove Even 236 CHAPTER NINE during periods when they were apparently most at odds, their correspondence is stiffly affectionate or at least formally correct in tone Nor is it always easy to disentangle the scientific vs clinical split between Pasteur and Roux from other sources of conflict between them But the task is worth pursuing, not least because it may provide yet another example of the persistent divide between scientific and clinical approaches to the problems of disease, animal experiments, and the ethics of human experimentation 6 THE TENSION BETWEEN PASTEUR AND ROUX No small part of the tension between Pasteur and Roux was "merely" personal In their physical appearance, political views, and everyday mode of life, they were an odd couple indeed Pasteur, a sturdily built, financially secure family man with conservative political leanings, was the quintessential "bourgeois", Roux, a tubercular, ascetic but mercurial "confirmed" bachelor of vaguely leftist or transcendental political views, was the quintessential "bohemian" by contrast Roux, it might even be said, was a sort of Don Quixote to Pasteur's Napoleon 7 Given the personal differences between them, Pasteur and Roux were perhaps bound to clash Even the personal traits they did have m common pointed toward that outcome both were stubborn, aloof, severe, demanding of others, quick to take offense, and given to outbursts of temper And once Roux joined the Pastonan team, their personal differences were exacerbated by a sense of rivalry between master and employee as they worked toward vaccines against anthrax and rabies Behind the scenes, they were sometimes competing with each other as much as they were collaborating, and there are signs that Roux resented his subordinate role and Pasteur's highhanded treatment of him Actually, it is in some ways surprising that Roux ever became part of the Pastonan enterprise in the first place When he joined Pasteur's laboratory in 1878 at the age of twenty-five, Roux had not yet received the M D degree toward which he was struggling despite his straitened financial circumstances He had been a student of Pasteur's own disciple, Emile Duclaux, at the medical college at Clermont-Ferrand, after which he pursued clinical training in Pans The French army covered the costs of his medical studies and paid him a modest stipend on the understanding that he would serve as a military physician for ten years after completing his training In 1877, however, Roux was dismissed from the army for "disciplinary reasons," presumably some form of insubordination 8 DOUBTS AND ETHICAL DILEMMAS 237 After his discharge from the army, Roux was making his way, if just barely, by treating poor people for varicose veins, when Duclaux recommended him to Pasteur Up to that point, Pasteur had selected his research assistants from the pool of postgraduate "agreges-preparateurs" in the physical sciences at the Ecole Normale Supeneure, in which capacity he had himself served in his youth Quite deliberately, Pasteur had not yet allowed a medical man to jom his team 9 It is too often forgotten that Pasteur had no M D and was not legally qualified to practice medicine Perhaps partly for that reason, he was openly disdainful of doctors, saying that they were too interested in making money and in high society to meet the rigorous demands of experimental scientific research Yet now, in 1878, Pasteur decided to expand his tight research circle to include this feisty doctor-intraining who had just been dismissed from the army for insubordination Why? The decisive factor, surely, was that Roux had been recommended by Duclaux, Pasteur's favorite disciple and collaborator But Pasteur had also come to see the need for a veterinarian or medical man as he began to direct the resources of his laboratory toward a frontal assault on the infectious diseases, beginning with anthrax, a lethal and economically significant disease of sheep A host of experiments on living animals was now in prospect, and Pasteur wanted a research assistant who was at least skilled in the techniques of injection Thus Roux began his career with Pasteur in 1878 as an animal "inoculator "10 From the beginning, he performed superbly at his technical tasks, and he was soon participating in the search for attenuated anthrax cultures as well as injecting them into experimental animals As we have seen in Chapter Six, visible signs of discord between Pasteur and Roux surfaced during the famous trial of an anthrax vaccine at Pouillyle-Fort in 1881 The master's conduct in that affair could not have soothed any prior tension between them, and it also gave Roux a clear appreciation of just how boldly, even recklessly, Pasteur was willing to apply vaccines in the face of ambiguous experimental evidence about their safety or efficacy In this quest for vaccines, as in his earlier research, Pasteur displayed the scientist's attraction to "signals" amid the "noise," and he exuded the bold self-confidence that is often found in scientists who have revealed such patterns to outside acclaim Roux, in sharp contrast, proceeded with what I choose to call a clinician's caution in the face of inconvenient or anomalous evidence In his own research on vaccines, Roux tended to draw carefully limited conclusions from the experimental evidence at hand When it came to the results of injecting vaccines into living animals, he (unlike Pasteur) expected and even appreci- 238 CHAPTER NINE ated all the vagaries of their individual responses. As we shall see, Roux was especially circumspect in the case of the application of rabies vaccines to human beings, much to Pasteur's exasperation. As they worked toward a vaccine against rabies, Pasteur and Roux were also headed toward a series of conflicts that once or twice brought them to the verge of complete and permanent rupture. The issues that divided them most deeply had to do with the ethics of human experimentation: specifically, how much evidence of what sort and what degree of reliability should be required from animal experiments before one could justify the application of vaccines to human victims of rabid animal bites? The most visible sign of an open split between Pasteur and Roux over these issues came at the single most dramatic moment in Pasteur's career: his decision, in early July 1885, to treat Joseph Meister with a vaccine that had thus far been tested only on dogs. For current purposes, the most striking point to notice is Roux's conspicuous absence from the Meister story, which is odd, to say the least. Not only was he Pasteur's leading collaborator on rabies; by then, he had also attained his M.D. degree and was (unlike Pasteur) qualified to practice medicine. He could have treated Meister, had he been asked and willing to do so. In fact, it seems very likely that Roux simply refused to participate in Meister's treatment in any way. And it is equally likely that he did so because he considered Pasteur's treatment of Meister to be a form of unjustified human experimentation.11 Roux's clinical caution or scruples thus kept him from taking part in what would become the most glorious episode in the Pastorian saga. Since Pasteur could not himself legally perform the injections on Meister, and since Roux presumably refused to do so, Pasteur had to find more obliging medical men to play that role. As we have seen in Chapter Eight, Pasteur found them in Drs. Vulpian and Grancher. In fact, it was Dr. Grancher, not so incidentally Pasteur's employee, who actually performed the injections on Meister.12 The participation of Vulpian and Grancher in the treatment of Meister might seem to pose a problem for my suggestion that Roux's clinical background helps to explain his disagreements with Pasteur. After all, Vulpian and Grancher were doctors, too. Like Roux, they had been exposed to the clinical mentality or ethos, and yet they seemed to have few qualms about the proposed treatment of Meister. But neither Vulpian nor Grancher had Roux's deep experience with rabies. More important, they also lacked Roux's intimate knowledge of the contents of Pasteur's laboratory notebooks. Except for Pasteur himself, no one knew better than Roux just how much and what sort of experimental evidence then existed as to the safety and efficacy of the vaccine used to treat young Meister. In Roux's eyes, quite clearly, the evidence did not jus- DOUBTS AND ETHICAL DILEMMAS 239 tify Pasteur's decision to treat young Joseph Meister with the vaccine in question In his famous paper of 26 October 1885, Pasteur tried to meet in advance any ethical concerns about his decision to treat Meister by insisting that he had already made fifty dogs immune to rabies, without a single failure, by the same method he then used to treat Meister beginning on 6 July 1995 Pasteur continued with the following crucial passage "My set of 50 dogs, to be sure, had not been bitten before they were made refractory [\ e, immune] to rabies, but that objection had no share in my preoccupations, for I had already, in the course of other experiments, rendered a large number of dogs refractory after they had been bitten " 13 This claim leads us toward a close, if not exhaustively detailed, analysis of Pasteur's laboratory notebooks in order to address three compelling questions about the results of his animal experiments at the time he decided to treat Joseph Meister (1) Exactly how many dogs had been rendered immune to rabies after they had already been bitten by rabid animals7 (2) By what method or methods had these dogs been rendered immune and with what rate of success7 And (3) exactly what meaning can be attached to Pasteur's claim that he had already rendered fifty dogs immune to rabies "without a single failure" by the same method used on young Joseph Meister7 The attentive reader will recall that very similar questions were raised, explicitly or implicitly, by Dr Michel Peter during the famous 1887 debates at the Academie de medecine PASTEUR'S LABORATORY NOTES ON RABIES VACCINES In Chapter Seven, we were introduced to Pasteur's remarkably empirical, "hit-or-miss" efforts to find a reliable rabies vaccine Before rabid spinal cords became the focus of his attention, he tested a wide variety of other techniques as well, including the injection into dogs of various quantities of blood and nervous tissue taken from animals dead of rabies Throughout these early and almost haphazard trials, Pasteur did sometimes produce immune dogs, even when other dogs injected simultaneously by the same method died of rabies In one fairly typical example from late June 1884— unusual only by virtue of its relatively grand scale—Pasteur injected fourteen dogs subcutaneously with a broth prepared from the brain of a rabbit just dead of a highly virulent rabies virus that had been passed sequentially through fifty-six earlier rabbits Of the fourteen dogs so inoculated, nine died of rabies but the other five survived and proved resistant to subsequent injections of virulent rabies 14 240 CHAPTER NINE Whenever and however an immune dog emerged from such experiments, Pasteur considered it "vaccinated " By August 1884, he had about twentyfive such dogs, whose immunity he then demonstrated in experiments before the French Rabies Commission, which was appointed that same year at his request But none of these dogs had sustained rabid animal bites before their inoculations, and the methods used on them often resulted in rabies when applied to other dogs No one outside the Pastonan circle had any way of knowing this fact, including presumably the members of the official French Rabies Commission By keeping what he called the "details" of his experiments out of public view, Pasteur repeatedly conveyed a rmsleadmgly optimistic impression of the actual results recorded in his laboratory notebooks That judgment applies with full force to the results of Pasteur's post-bite trials on dogs 15 Among Dr Peter's explicit complaints was that Pasteur failed to specify what he meant when he claimed that "a large number of dogs" had been rendered immune to rabies after sustaining rabid animal bites The first remarkable conclusion to emerge from a close study of Pasteur's laboratory books is that this "large number" was in fact less than twenty More important, in the course of producing immunity in these bitten dogs—no more than sixteen, by my count—Pasteur failed to save ten dogs treated at the same time and by the same methods In the case of three or four of the dogs that died despite their treatments, Pasteur believed their deaths resulted from some cause other than rabies and therefore imagined that they could be counted as "successes " This is but one striking example of the wishful thinking, or self-deception, found scattered throughout his laboratory notebooks on rabies There was obviously no basis for including these dogs among the successfully vaccinated, for they never had a chance to demonstrate their alleged immunity to rabies At best, a case could be made for excluding them from any list of failures, but only if they were discounted entirely More than that, the success rate in these dogs treated after sustaining rabid bites was essentially no different from the survival rate of otherwise similar dogs that were simply left alone after their bites Actually, in these experimental trials of rabies vaccines, Pasteur hardly lived up to his reputation as a rigorous practitioner of the "controlled experiment " In most cases, he did not employ control dogs at all While conducting his trials on twenty-six bitten dogs, he used only seven controls Of these seven dogs left to suffer their fate without treatment, five were still alive at the time Pasteur treated Joseph Meister16 One of the surviving five control dogs did eventually die of rabies in September 1885, but by then one of Pasteur's sixteen D O U B T S AND E T H I C A L D I L E M M A S 241 Table 9.1 Results of Pasteur's "post-exposure" experimental trials on dogs after they had been bitten by a rabid dog, August 1884 through May 1885 Date No of Dogs Treated after Bitten by Rabid Dog No of Dogs Succumbing to Rabies 3 3 1 2 1 5 5 6 0 2 1 1 0 2 3 1 26 10 August 1884 October 1884 November 1884 January 1885 February 1885 March 1885 April 1885 May 1885 Total "Success" rate 16/26 = 62% Date Controls Dogs Left Untreated after Bitten No of No Untreated Succumbing Controls to Rabies October 1884 November 1884 March 1885 Total 2 1 4 0 1 2 7 3 "Survival" rate 4/7 = 57% allegedly "vaccinated" dogs had also died of the disease after an unusually long incubation period At any rate, four of the control dogs apparently never did develop rabies Choosing the most favorable and least favorable interpretations of Pasteur's results, and depending on the precise moment of calculation, it turns out that the survival rates for the two sets of dogs fall into the following ranges for the dogs treated by Pasteur, 50 to 78 percent, for the untreated control dogs, 57 to 71 percent (See table 9 1 ) Given the small number of dogs in question (especially in the case of the controls) and the uncertainties of diagnosis and incubation period, the ap- 242 CHAPTER NINE parent precision of these survival rates is more than a bit specious But there can be no doubt that the results of these post-bite trials on twenty-six dogs were ambiguous at best Had Dr Peter or other critics been aware of these "details," they surely would have asked Pasteur to explain exactly how his post-bite trials provided any justification for the decision to treat Joseph Meister And the question would have been hard for Pasteur to ignore For in his famous paper of 26 October 1885 on Meister and Jupille, it deserves repeating here, he openly admitted that of the last fifty dogs he had vaccinated "without a single failure" before treating Meister, none had been previously exposed to rabid dog bites It was, he said, precisely because of the "large number" of other dogs he had already rendered immune after rabid bites that he felt able to put this concern out of his mind If this claim already seems odd in view of the actual results of Pasteur's post-bite trials, it becomes more suspect still when close attention is paid to the methods applied to these twenty-six bitten dogs As we have almost come to expect, Pasteur evaded the issue in public When speaking of the dogs he had rendered immune after rabid bites, he said not a word about the method or methods by which this feat had been accomplished But the implication, surely, was that they had been treated with injections of desiccated spinal cords For otherwise, his post-bite trials would seem devoid of any pertinence to Meister's case Unless the immune dogs had been treated by desiccated cords, why would they have given him any reassurance as he prepared to treat Joseph Meister by that method 7 True, Pasteur did imply that some sort of distinction could be drawn between the treatment applied to his bitten dogs and the treatment applied to Meister after invariably successful results m the last fifty (unbitten) dogs u But he left the nature of that distinction entirely unclear In the face of such reticence, it was natural to assume that Pasteur had applied the same method in both cases, but had perfected it in the (unspecified) interval between his post-bite trials and his experiments on the last fifty dogs In fact, however, Pasteur had switched to a radically new method in his experiments on this last group offifty (or perhaps forty) unbitten dogs It was essentially the technique applied to Joseph Meister beginning on 6 July 1885 But it differed drastically from the methods previously used to treat the twentysix bitten dogs As only Pasteur's laboratory notebooks reveal, not a single one of those twenty-six dogs, including of course the sixteen that did develop immunity to rabies, was treated by the method later applied to young Meister18 Actually, the bitten dogs were treated by three different methods, none of which was ever described in print Until 26 October 1885, when Pasteur reported that he had treated Meister and Jupille by injecting them first with dried rabid cords and then with DOUBTS AND ETHICAL DILEMMAS 243 progressively fresher cords, the only announced method was the injection of rabid nervous tissue after it had been attenuated by serial passage through monkeys. When he disclosed this technique in May 1884, Pasteur claimed that the monkey-attenuated vaccine was yielding highly promising results in experiments on dogs.19 But none of those promising results, it turns out, came from experiments on dogs already exposed to rabid bites. The three methods that Pasteur in fact applied to his bitten dogs are worth revealing here, especially since the third did involve the injection of dried spinal cords, but in a manner that differed strikingly from the one used later on Meister. And the special features of this third method will soon lead us into a discussion of Pasteur's theoretical views on immunity, which underwent a dramatic shift as a result of his work on rabies. PASTEUR AND HIS FIRST METHOD WITH RABID SPINAL CORDS: FROM MOST VIRULENT TO LEAST VIRULENT Pasteur's post-bite trials, recorded in widely scattered entries in two of his laboratory notebooks, ranged in date of origin from August 1884 to midMay 1885. His first two methods need not detain us for long. First, in the case of the first seven of the twenty-six treated dogs, the initial inoculation was prepared from the brain of rabbits just dead of a rabies virus that had been augmented in virulence by serial passage through other rabbits. Four of these seven dogs were dead by January 1885, though Pasteur had reason to believe that at least two and perhaps three had died of some cause other than rabies. The three surviving dogs proved immune to subsequent inoculations of virulent rabies.20 Second, in the next eight treated dogs, the first injection was prepared from the brain of a guinea pig just dead of rabies of more or less ordinary virulence. Of these eight dogs, three soon died of rabies. Once again, the survivors had been rendered immune to rabies.21 On 13 April 1885, when the sixteenth bitten dog sustained its first injection, Pasteur began a systematic program of taking spinal cords from rabbits dead of "fixed" or highly virulent rabies and suspending them in desiccated air. From that point through the next five weeks, up until 22 May 1885, when a last group of six dogs received their final injections, Pasteur used these suspended spinal cords as part of a regular series of injections that he hoped would prevent rabies in these last eleven bitten dogs. Seven of the dogs, including five of the last six, were still alive on 16 June 1885. On that day, roughly three weeks after the last six dogs had received their final injections and three weeks before Joseph Meister appeared at his laboratory door, Pasteur "sacrificed" the five survivors so that he could use their cages for 244 CHAPTER NINE The chart below indicates, in chronological order, some of Pasteur's most significant animal experiments and human trials on potential rabies vaccines using desiccated rabid spinal cords. 13 Apr Begins systematic study using dried spinal cords to treat eleven dogs already bitten by rabid dogs: But moves from most virulent to least virulent cords. • 2 May <- 22 May Ends this set of experiments with ambiguous results a. < •25 May < 28 May Begins treatments of presumably rabid M.Girard: one injection with a dried spinal cord Girard released from hospital, apparently cured Crucial set of experiments begin, using the "Meister Method". [See Figure 9.2] 22 June Begins treatment of symptomatic rabies patient, Julie-Antoinette Poughon. Two injections with dried spinal cords 23 June Girl dies - <— 6 Jul Begins treatment of Joseph Meister (continues with daily injections through 16 July) - 20 Oct Begins treatment of Jean-Baptiste Jupille (continues with daily injections through 29 Oct) - 26 Oct Pasteur's famous memoir on Meister and Jupille Figure 9 1 Pasteur's path to his rabies vaccine, 13 April 1885 through 6 July 1885 Animal experiments and human trials with dried spmal cords DOUBTS AND ETHICAL DILEMMAS 245 other experimental animals 22 As his experiments multiplied, this practice became increasingly common, the "sacrificed" dogs being dispatched by lethal injections of strychnine If necessary because space was lacking, this practice nonetheless came at a cost, for these dogs might have developed rabies after an unusually prolonged period of incubation—as some other animals certainly did But Pasteur's laboratory notes reveal a much more remarkable and more significant feature of his experimental trials on these last eleven bitten dogs In all eleven, as noted, injections were prepared from suspended rabid spinal cords But here the cords were deployed in a sequence precisely the reverse of the one soon to be adopted in the case of young Joseph Master In Meister's case, Pasteur began with cords that had been drying out for roughly two weeks and then moved to cords that were progressively less dry until, finally, he reached a fresh and highly virulent cord In the case of the eleven bitten dogs, he began with a fresh cord and then moved to drier and drier cords until, finally, he reached a fully dried-out cord To anyone familiar with Pasteur's earlier work on other vaccines, this latter modus operandi is astonishing In developing his vaccines against chicken cholera, anthrax, and swine fever, he had first injected attenuated strains of the implicated microbes and then moved to progressively more virulent strains Yet here, in these trials with suspended spinal cords on already bitten dogs, he began with fresh, highly virulent cords and only then moved to drier, more attenuated cords His attempts to prevent rabies in these bitten dogs had now taken a direction precisely the opposite of that followed in all his earlier work on vaccines But this volte-face is not quite so mysterious as it seems at first sight For it was associated with a dramatic shift in Pasteur's conception of immunity In the course of his work on rabies, Pasteur switched from a biological theory of immunity to a modified chemical theory of a sort he had often disparaged when it had been advanced by his critics and competitors He did so in an attempt to make sense of the variable and sometimes confusing effects that his experimental animals displayed after infection with the rabies virus The conclusions that Pasteur drew from these confusing effects were themselves more than a bit confusing and susceptible to widely divergent interpretations But they also bespeak a remarkable flexibility of mind in the now aging Pasteur Actually, Pasteur never did invest as much time and energy in efforts to establish a theoretical basis for attenuation and immunity as he did in his more pragmatic, even "empirical," search for effective vaccines But throughout his work on chicken cholera, anthrax, and swine fever, he linked immunity with the biological, and particularly the nutritional, requirements of the pathogenic organism In the case of animals inherently 246 CHAPTER NINE immune to a given disease, he suggested that they presented the invading microbe with an internal "economy," "culture," or "environment" that was inimical to its development, either because their temperature was too high or because they lacked some substance essential to the microbe's life and nutrition. In animals rendered immune by recovery from a prior attack by preventive inoculations (Pasteur's "vaccines"), he supposed that each invasion by a given microbe (even in an attenuated state) removed a portion or all of some essential nutrient, thereby rendering subsequent cultivation of the same microbe difficult or impossible.23 But at some point during his work on rabies, Pasteur began to doubt the validity of this biological "exhaustion" theory at first in the case of rabies and then more generally. According to his own retrospective account, he began to adopt a chemical "toxin" theory for rabies as early as January 1884.24 A year later, his conversion was largely complete and no longer confined to rabies alone, as is clear from a long and unusually explicit theoretical entry of 29 January 1885 in his laboratory notebook.25 By then, he was growing increasingly confident that he had made an "immense discovery" of potentially "great generality"—namely, that the living rabies virus produced a dead, soluble, chemical "vaccinal substance" inimical to the further cultivation of the virus and therefore capable of producing immunity to rabies. Thus far, however, Pasteur chose to reveal this new theory only to "those who work alongside me"—that is, Charles Chamberland and Emile Roux, saying that he did not know how to "hide my ideas" from them. Sensibly enough, he planned to expose his theory to others only after it had been thoroughly tested by experiments "already underway."26 For present purposes, there is no need to explore the precise extent to which Pasteur's new position was justified by the evidence at hand. Nor is there any need to follow every twist and turn in his experimental and conceptual path to this conclusion. For now, it will suffice to draw attention to the sorts of considerations that lay behind his theoretical conversion and that can help us to understand why he ever tried to treat bitten dogs by moving from virulent (or fresh) to attenuated (or dried) spinal cords instead of the other way around. The first step in solving the puzzle is to notice Pasteur's increasing focus on the effects of injecting different quantities of the same virus into his experimental animals. In trying to make sense of the variable response of individual living organisms to infection with the rabies virus, he began to suspect that the variations depended more on the amount of virus injected than on its intrinsic virulence. As Pasteur reported in his unusually reflective (i.e., "theoretical") notebook entry of 29 January 1885, he had been led to this belief by two interrelated generalizations that seemed to be emerging DOUBTS AND ETHICAL DILEMMAS 247 from his experimental evidence: (1) injecting large quantities of a virus of given virulence produced a higher proportion of immune dogs than smaller quantities of the same virus—at least twice as high, by his reckoning; and (2) even when large quantities of a given virus did produce rabies in the inoculated animal, the disease often appeared much later than was usual with smaller quantities of the same virus. This second generalization upset Pasteur's prior assumption that length of incubation depended only on the inherent virulence of the injected virus. Both pieces of evidence thus pointed in the same direction: for a rabies virus of given virulence, the injection of large quantities seemed to produce a higher level of immunity than did the injection of small quantities. Pasteur also suggested that this generalization could explain why rabid dog bites so rarely produced immunity in the bitten dogs, whereas subcutaneous injections of this same "street rabies" into healthy dogs quite often did. The significant difference was that smaller quantities of the rabies virus were transmitted through bites than through subcutaneous injections. To Pasteur, such results seemed explicable only on the assumption that the rabies virus "manufactured" a nonliving vaccinal substance inimical to its own development. If immunity depended only on the intrinsic and inherited virulence of a living, reproducing rabies virus, then small quantities should produce the same effects as large. Pasteur had not yet managed— nor, indeed, did he ever manage—to separate this hypothetical chemical "vaccinal substance" from the rabies virus that presumably produced it. But as early as January 1885, this was his ultimate hope and goal. At the same time he pondered the possibility that a similar vaccinal substance was produced by the developing anthrax bacillus. In the case of rabies, Pasteur hoped to capture this chemical substance separately from the living virus by filtration. In the case of anthrax, he hoped that the hypothetical chemical vaccine could be found in vitro after the anthrax bacillus had been killed by heating at appropriate temperatures for appropriate periods of time. In both cases, Pasteur had quite suddenly become a convert to the modified chemical theory of immunity that he had so effectively criticized when it was advanced by Auguste Chauveau, Casimir Davaine, and Henri Toussaint, among others. Indeed, the techniques by which Pasteur now sought to isolate a nonliving vaccine against anthrax bear a striking resemblance to the techniques once deployed by his already deceased competitor, Toussaint— though Pasteur declined to say so out loud.27 At any rate, Pasteur's inability to separate the hypothetical vaccinal substance from the living rabies virus left him with a delicate task. The goal, of course, was to inject a maximum amount of the alleged vaccinal substance and a minimum amount of living rabies virus. But since no way could be 248 CHAPTER NINE found to separate the two, the results of any given injection would depend on the relative amounts of living virus and hypothetical vaccinal substance And since the virus was the presumed source of the vaccinal substance, the quantity of this vaccinal substance perforce depended partly on the amount of virus injected along with it If the amount of injected virus was too small—as in the case of rabid dog bites—so too would the quantity of vaccinal substance be too small to produce immunity In such a case, the supply of vaccinal substance would be inadequate to prevent the further development of the virus, and rabies would thus eventually appear in the inoculated animal Although Pasteur was understandably reluctant to say so himself, this interpretation of his results had the advantage for him of being almost infinitely flexible Almost any result could be explained by adopting appropriate—and unvenfiable—assumptions about the relative amounts of living virus and associated vaccinal substance By the time Pasteur presented his modified chemical theory of rabies immunity in print—briefly in the famous memoir of 26 October 1885 on Meister and Jupille, and more extensively m a paper of January 188728—he had adopted the technique of beginning with dry rabid spinal cords and moving to progressively fresher ones As Pasteur pointed out, most commentators assumed that this technique was equivalent to beginning with a highly attenuated virus and only then moving to more virulent strains But he argued instead that the vaccinal properties of his cords depended not on the inherent virulence of the virus they contained—indeed, the virulence might be the same in all of the cords, dry or fresh—but rather on the relative amounts of living virus and vaccinal substance in them Specifically, Pasteur suggested that the drying process might somehow reduce the amount of living virus—without changing its virulence—more rapidly than it reduced the amount of nonliving vaccinal substance And so, after a period of roughly two weeks, there might remain enough vaccinal substance to prevent the reduced amount of living rabies virus from developing further and thus giving rise to rabies Ideally, of course, one would prefer to use spinal strips in which all of the living virus had been destroyed while some vaccinal substance still remained And Pasteur predicted that such a "dead" vaccine against rabies would one day be found, though he had not yet been able to perfect one himself But in January 1885, when Pasteur also expressed the hope that he might someday isolate a "dead" rabies vaccine, his interpretation of rabies immunity was very different from the one he had settled on two years later So, too, were the techniques by which he then sought to produce immunity in his experimental animals His laboratory notes from early 1885 make it DOUBTS AND ETHICAL DILEMMAS 249 abundantly clear that a reliable rabies vaccine continued to elude him Well into the spring of 1885, he had still not settled on any one approach to the problem He continued to inject dogs, bitten and unbitten, with several very different sorts of potential vaccines—and the results were inconclusive and confusing 29 True, Pasteur had for some time displayed a special and growing interest in the possibilities of a vaccine prepared from desiccated spinal cords In his notebook entry of 29 January 1885, Pasteur even referred to experiments with desiccated spinal cords of low virulence as perhaps the most important test for his new chemical theory of rabies immunity But he had not yet begun systematic trials of such potential vaccines And if his laboratory notebook thereafter devotes increasing attention to desiccated spinal cords, it also reveals that he long remained uncertain about the precise point at which desiccated cords might become at once nonlethal and capable of producing immunity when injected into dogs In fact, the experiments actually recorded in Pasteur's laboratory notebook through mid-May 1885, including especially his trials on bitten dogs, suggest that even then he remained uncertain about the basic issues raised in his notebook entry of 29 January 1885 From that point on, he made several more or less systematic attempts to compare the effects of injecting large and small quantities of rabid nervous tissue of presumably constant virulence—the very issue that had pointed him toward his new chemical theory of rabies immunity in the first place Another related issue—more salient for the moment—concerned the speed with which immunity had to be achieved if there was to be any chance of success in the hfe-and-death struggle against the rabies virus In his notebook entry of 29 January 1885, Pasteur endorsed the position that immunity had to be established quickly—perhaps as soon as the eighth day certainly no later than the fifteenth—if a dog was to escape the lethal effects of exposure to the rabies virus 30 To judge from the experiments recorded in his laboratory notes from that point through mid-May 1885, Pasteur seemed then to assume that virulent strains of the rabies virus—or, more precisely, fresh rabid spinal cords—might produce immunity more quickly than drier cords At this point, unlike two years later, Pasteur presumably thought that fresh rabid spinal cords might contain a greater quantity of his hypothetical vaccinal substance than drier cords In any case, he often chose to begin his series of preventive inoculations with a very fresh cord (what he would, at other times, call "a highly virulent" virus), presumably in the hope that it would produce immunity quickly A striking example of this practice is found in his last eleven post-bite trials on dogs In all of them he began the series of injections with a highly virulent (fresh) rabid 250 CHAPTER NINE spinal cord and only then moved to less and less virulent (1 e , or drier and drier) cords 31 Within a few months, however—certainly by April 1885—Pasteur began to notice that the incubation penod of rabies in at least some of his experimental animals was more prolonged when they were injected with dry instead of fresh cords, which presumably meant that dry cords conferred some degree of immunity in the case of some animals 32 For quite some time, Roux had noticed the same trend, although a range of experimental contingencies, including especially the ambient temperature, could easily obscure any clear pattern 33 But could Pasteur have had this vaguely emerging pattern in mind when, on 2 May 1885, he decided to treat M Girard, his first rabid "private patient"7 The evidence is circumstantial, to be sure, and Pasteur's laboratory notebooks do not explicitly indicate that the results of such animal experiments lay behind his decision to treat Girard with a highly desiccated spinal cord What we do know for sure is that within three days of Girard's release from the hospital—presumably "cured" of rabies by just one such injection—Pasteur suddenly undertook a systematic series of experiments in which dogs were "treated" by a sequence of injections that began with very dry spinal cords and ended with very fresh cords If Girard's presumed "cure" did inspire or encourage this new experimental program (to repeat a suggestion made in Chapter Seven), it would seem that Pasteur was once again exceptionally lucky, especially given that the diagnosis of rabies in M Girard was almost surely mistaken But I suspect that Pasteur, were he here to defend his work, would insist yet again not only that chance favors the prepared mind, but also that "luck comes to the bold "34 PASTEUR'S EXPERIMENTS ON DOGS BY THE "MEISTER METHOD": LEAST VIRULENT TO MOST VIRULENT SPINAL CORDS In any case, Pasteur's laboratory notebooks amply confirm that, at the time he undertook to treat Meister, he had not yet produced anything remotely approaching "multiple proofs" of the efficacy of his method on "diverse animal species " But that is the least of it For the notebooks also reveal that Pasteur had not yet met the much less demanding criteria to which he referred m his famous paper on the Meister case, three months after the boy's treatment had been completed In fact, the notebooks provide no evidence that Pasteur had actually completed the animal experiments to which he appealed in justification of his DOUBTS AND ETHICAL 251 DILEMMAS 2 May Treatment of Girard • 25 May Girard realeased from hospital "cured" • 28 May (1) Ten dogs injected daily with spinal cords beginning with dried cords and movmg to increasingly fresh (more virulent) cords (9 Jun: last injection) • 3 Jun (2) Ten more dogs treated the same way (18 Jun: last injection) 22-23 June Treatment and death of Julie-Antoinette Poughon • 25 June < (3) Ten more dogs treated the same way • 27 June (4) Ten more dogs treated the same way (5)Projects some experiments on 10 more dogs, but apparently never carried out • 6 Jul Begins treatment of Meister Experimental results as of 6 July, 1885: V V (3) (4) All All ten ten dogs dogs OK* OK* * but last injection 9 July (2) All ten dogs OK (D All ten dogs OK Figure 9.2. The results of Pasteur's experiments on dogs treated by the "Meister Method," 28 May 1885 through 6 July 1885. 252 CHAPTER NINE decision to treat Meister Rather, they show that as of 6 July 1885, when Meister's treatment began, Pasteur had just begun a series of vaguely comparable experiments on forty dogs (and conceivably on fifty, though I have not yet been able to identify these last ten dogs) As of that date, according to the laboratory notebooks, only twenty of the forty to fifty experimental dogs had even completed the full series of "vaccinal" injections And none of the dogs had survived as long as thirty days since their last (and highly lethal) injection (See fig 9 2 ) From a few earlier experiments, Pasteur might reasonably have surmised that rabies symptoms typically appeared between the seventeenth and twenty-sixth day in dogs inoculated with highly virulent rabies virus That these twenty dogs had not yet displayed fatal symptoms of rabies, three to four weeks (twenty-three to thirty days) after they had been injected with a highly virulent rabies virus, was the best evidence Pasteur had of the safety and efficacy of his antirabies vaccine at the time he decided to treat young Joseph Meister 35 Furthermore, as Pasteur himself conceded, not a single one of these experimental dogs had first been bitten or otherwise inoculated with rabies before being "treated" by the method used on Meister Against this background, it should come as no great surprise that Pasteur never did publicly disclose the state of his animal experiments on the "Meister method" as they stood at the point at which he decided to treat the boy Nor, indeed, have they been revealed in print until now They are recorded only in Pasteur's private notebook of that period, which, like the other one hundred laboratory notebooks he left behind at his death in 1895, remained in the hands or control of his immediate family until the mid-1970s Even now, the notebooks have only begun to be subjected to the close scrutiny and analysis they deserve But it is already clear, and should not surprise us, that the most acute critics of Pasteur's treatment for rabies were medical men Even Dr Grancher, who performed the injections on Meister and other early subjects of the Pastonan treatment, later admitted that "the great majority of doctors did not believe in [Pasteur's] antirabies vaccine "36 If some of these critical doctors were motivated in part by personal hostility toward Pasteur and by their concern over the intrusion of the new experimental science into their traditional domain, they also directed sometimes telling attention to the pertinent ethical issues, and their cautious skepticism clearly owed something to the clinical ethos or mentality they shared with Roux In fact, as Dr Peter suspected and as Dr Roux knew full well, the decision to treat Meister was ethically dubious by then prevailing standards, as was some of the rest of Pasteur's conduct in his headlong and headstrong quest for vaccines DOUBTS AND ETHICAL DILEMMAS 253 ROUX AND PASTEUR AFTER MEISTER: PARADOXES AND PUZZLES The story just told leaves one or two puzzles unresolved For if Roux had such deep and long-standing misgivings about Pasteur's conduct, including notably the decision to treat young Joseph Meister, why did he return to the master's laboratory a few months later to participate m its subsequent work on rabies7 And why did he keep his misgivings private, even after Pasteur's death 7 Despite Roux's alleged concern with ethical issues, did he not himself take part in a lifelong "cover-up" of the real Pasteur and the real story of his work on vaccines7 Let us begin with the first of these questions, which is perhaps the easiest to answer Why did Roux return to Pasteur's laboratory and its work on rabies7 To ethical absolutists or conspiratorial muckrakers, the answer may come as something of a disappointment For Roux's return is probably best explained by the simple fact that he came to believe in the overall safety and efficacy of the original Pastonan vaccine To be sure, Roux continued to have serious differences with Pasteur over matters of detail and about particular cases Even when he did rejoin the Pastonan rabies team, he retained much of his clinical skepticism On balance, however, he had become a convert to Pasteur's cause One powerful factor, of course, was the increasingly evident success of Pasteur's vaccine in almost all human cases But Roux may have been even more impressed by the rapidly expanding body of favorable evidence from animal experiments For Pasteur had by no means abandoned or curtailed his animal research on rabies in the wake of his celebrated success with Meister And the evidence from those later animal experiments seemed to vindicate Pasteur's original intuition Once again, or so Roux had now come to believe, Pasteur had been "on the right track" even before his experimental evidence was fully convincing to others Luckily for Pasteur, Roux's "conversion" came just m time to offset a swelling tide of criticism from Dr Peter and other clinicians In a very revealing letter of 4 January 1887, on the eve of the debates with Dr Peter at the Academie de Medicine, Roux advised Pasteur that he could spare himself much "trouble and fatigue simply by extracting from your notebooks the details of the experiments on the vaccination of dogs already bitten [l e , healthy dogs that survived rabies after having been inoculated with the virus through the bites of rabid dogs] " Those experiments, Roux continued, "are capital and justify the application of the method to man "37 Inexplicably, Pasteur never did follow this sage piece of advice 254 CHAPTER NINE In any case, Roux's letter suggests that by January 1887 he had become convinced that the accumulated evidence from animal experiments was now sufficient to establish the basic safety and efficacy of Pasteur's treatment for rabies By then, somewhat paradoxically, Pasteur had already benefited from Roux's prior skepticism about the treatment, which was well known to those within and close to the Pastonan circle The most spectacular example of this paradoxical benefit came in the case of one of Pasteur's most blatant "failures," a boy who had died of rabies in October 1886 in spite of, or even because of, the Pastonan treatment Here again Pasteur's conduct seems ethically dubious, and here again the episode remained private until disclosed a half century later by his nephew Adrien Loir According to Loir, whose basic credibility we now have good reasons to accept, Roux discovered, through animal experiments carried out with material taken from the boy's brain upon autopsy, that the boy had died of rabies Without knowing of this evidence, the boy's aggrieved and angry father had already accused Pasteur and his collaborators of killing his son and threatened to sue Loir reported that Pasteur, then resting at a villa in Italy for the sake of his fading health, listened calmly to the circumstances of this case, with "serene" confidence in his method of treatment Given his usual caution and clinical mentality Roux was almost surely less serene, but he nonetheless placed himself on Pasteur's side at this crucial juncture With the collusion of other authorities, Pasteur and Roux managed to keep the full circumstances of the boy's death out of the public eye, and no legal action was taken Toward this end, Roux's participation was crucial 38 Even so, Roux continued to display his clinical caution He and Pasteur still disagreed, especially because Pasteur had introduced a modified version of his original treatment in cases where subjects had been severely bitten (especially by wolves) or had presented themselves for treatment only after a long delay Roux was clearly skeptical about this new "intensive method" of treatment, as Pasteur called it It seems likely that Roux's skepticism was based partly on his usual concern for convincing evidence from prior animal experiments He was especially concerned about Pasteur's cavalier resort to highly virulent cords in such cases In a letter of 10 April 1887 to Dr Grancher, having perhaps heard once too often of Roux's reservations about the "intensive method," Pasteur wrote that "Roux is decidedly too timid " "I understand his scruples," Pasteur continued, "without accepting them [sans les approuver] "39 For me, no single piece of documentary evidence better captures the difference between Pasteur's scientific as opposed to Roux's clinical mentality It is powerfully reinforced by the testimony of Dr Grancher, who several years after treating Joseph Meister had this to say about Pasteur's approach to rabies vaccines "Pasteur lacked prudence in DOUBTS AND ETHICAL DILEMMAS 255 medical matters He had made no reservations as to the possibility of partial failures [of his rabies vaccine] Had he been a doctor, he would have instinctively taken some precautions by foreseeing the possibility of [occasional] failures "40 ROUX'S PUBLIC RETICENCE ABOUT PASTEUR'S CONDUCT: ANOTHER SIGN OF HIS CLINICAL MENTALITY? This brings us, finally, to the other puzzles posed at the outset of the preceding section Those questions can be collapsed into one Why did Roux remain forever in the Pastonan fold and forever silent about Pasteur's ethical indiscretions, some of which came at his own expense7 This question, which has no easy answer, gains in force when we recall that Roux did not merely choose to conceal what he knew about the less savory features of Pasteur's conduct in the quest for vaccines Quite the opposite Roux played an active part in the construction of the heroic legend of Louis Pasteur Whatever he may have said to his own disciples in private conversation, Roux was a staunch public defender of the Pastonan faith Surely part of the explanation lies in the fact that Roux's own career and reputation were so closely linked with Pasteur's While it seems unlikely that the bohemian Roux was concerned about "job security" in any usual sense, he clearly did become increasingly protective of the reputation of the enterprise with which he had been associated throughout his career and which was, after all, the main source of his claim to fame In the end, however, I would like to suggest that another part of Roux's protective public stance toward Pasteur can be ascribed to the very clinical sensibility that brought him into conflict with the master in the first place To the extent that Roux retained vestiges of that mentality, he would have been sensitive to the sometimes irrational forces that drove the ill and aging Pasteur To the same extent, he would have been reluctant to disclose the master's ethical indiscretions after Pasteur's death Most important, perhaps, Roux's "clinical" tolerance for ambiguity may have allowed him to appreciate the virtues of the Pastonan enterprise as a whole even if he sometimes objected to the means by which its founder had achieved his ends Perhaps he appreciated, more than Pasteur himself, the exquisite ethical dilemmas the master had faced For the sake of history and his own place in it, Roux's clinical mentality, if that's the right word for it, came at a cost Like his students Charles Nicolle and Emile Lagrange, historians may wish that Roux had been less "scrupulous," or more forthcoming, about his long-standing disagreements 256 CHAPTER NINE with Pasteur Had he chosen to do so, Roux could easily have produced a revealing, even scandalous, public expose of Pasteur's conduct By choosing to do otherwise, indeed the opposite, Roux may well have confirmed Pasteur's judgment that he was "decidedly too timid " But we can appreciate, in a way that Pasteur could not, just how much the Pastonan enterprise would benefit from Roux's clinical sensibilities And we would not expect Roux to display that mentality vis-a-vis Meister only to abandon it in the case of Pasteur himself