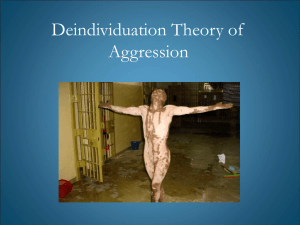

Deindividuation From Le Bon to the social identity model of deindividuation effects

advertisement