tracking-strategies-towards-a-general-theory-of-strategy-formation compress

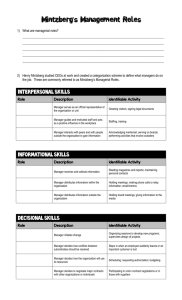

advertisement