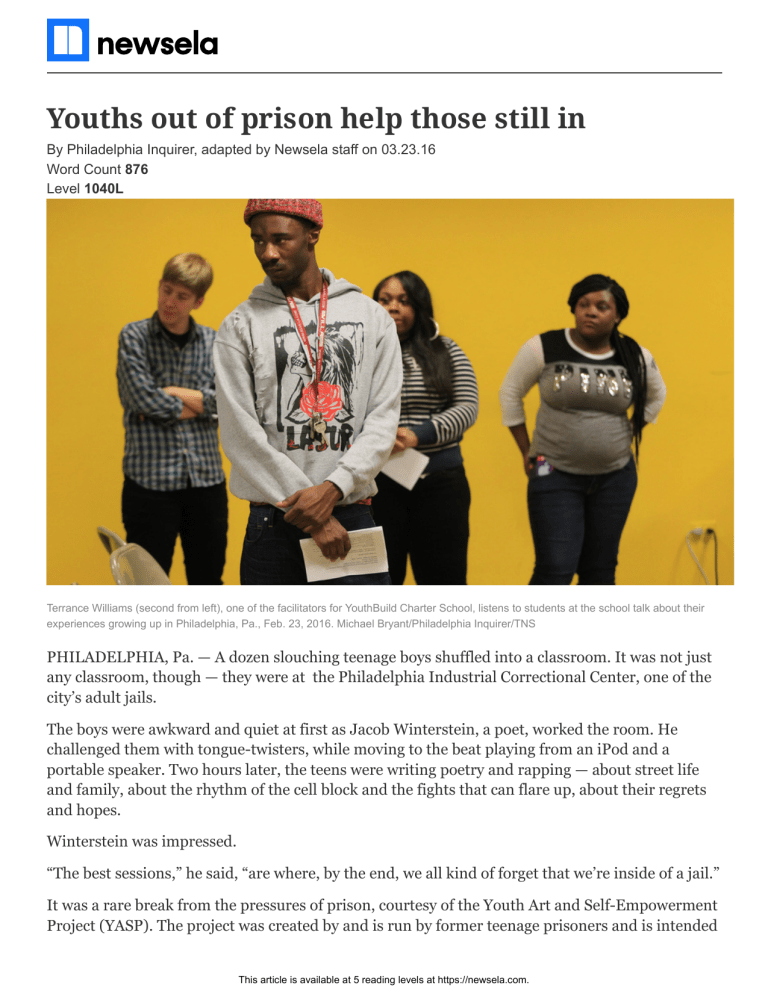

Youths out of prison help those still in By Philadelphia Inquirer, adapted by Newsela staff on 03.23.16 Word Count 876 Level 1040L Terrance Williams (second from left), one of the facilitators for YouthBuild Charter School, listens to students at the school talk about their experiences growing up in Philadelphia, Pa., Feb. 23, 2016. Michael Bryant/Philadelphia Inquirer/TNS PHILADELPHIA, Pa. — A dozen slouching teenage boys shuffled into a classroom. It was not just any classroom, though — they were at the Philadelphia Industrial Correctional Center, one of the city’s adult jails. The boys were awkward and quiet at first as Jacob Winterstein, a poet, worked the room. He challenged them with tongue-twisters, while moving to the beat playing from an iPod and a portable speaker. Two hours later, the teens were writing poetry and rapping — about street life and family, about the rhythm of the cell block and the fights that can flare up, about their regrets and hopes. Winterstein was impressed. “The best sessions,” he said, “are where, by the end, we all kind of forget that we’re inside of a jail.” It was a rare break from the pressures of prison, courtesy of the Youth Art and Self-Empowerment Project (YASP). The project was created by and is run by former teenage prisoners and is intended This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. to provide support to kids in Philadelphia’s adult prison system. It also acts to fuel a movement to treat kids as kids in Pennsylvania courts and jails. The Dangers Of Adult Incarceration “Young people are better off in the juvenile system,” a separate prison system for non-adults, said YASP cofounder Sarah Morris. “They’re less likely to be abused, to be assaulted, to commit suicide, and to be arrested in the future." Being in an adult prison only makes things worse for teens serving time, she said. Morris began visiting teenagers in adult prisons in 2004 and has stayed in touch with the young people she met. When they returned home, those former prisoners started talking about creating an organization. The goal would be to bring arts into the jails, to support kids during and after their prison terms, and maybe even to change the system. In 2006 YASP was founded. At any given time, there are 30 to 50 prisoners younger than 18 in Philadelphia’s adult jails. A few are transferred by judges from Juvenile Court, but the vast majority are sent automatically under a 1996 state law, Act 33. The law applies to kids 15 and older accused of serious crimes, like assault or robbery with a deadly weapon. YASP activists want to see Act 33 repealed. Inside Knowledge People like Terrance “T.A.” Williams know the law’s effect firsthand. He was 17 when he was locked up in adult jail on charges that included robbery and assault. “It was the worst time of my life,” he said. Williams, now 20 and out of jail, works part time as a YASP organizer. He talks to students about the school-to-prison pipeline and offers support for those returning from prison. The most important work, though, is in the jails on State Road. YASP organizers visit weekly, bringing with them poets, theater artists and visual artists to work with the boys at the Philadelphia Industrial Correctional Center, and the girls at the Riverside Correctional Facility. The Fewer The Better On a recent Saturday, Winterstein, 29, a teaching artist and a YASP regular, headed to the women’s prison. Often, there are no teens there, or there are only one or two. “It’s the only teaching gig where you hope the kids don’t show up,” he said. “It means they’re not in jail.” There were two kids, though — 17-year-old girls who have been in just a few weeks each, and who are sharing a cell. The girls were cautiously enthusiastic. They talked about poetry, about a rap they were working on together, about their hopes of getting back on track and going to college, and about a novel one was working on, an adventure story about people “who want to live in a free society.” This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. Welcome Visitor Romeeka Williams, 22, a YASP organizer from North Philadelphia, spent seven months in that unit when she was a teen. “Being locked in a cell 24 hours a day, it was a blessing for [YASP] to come and help us let our emotions out,” she said. Williams was released in 2011, but her prison record stayed with her. “We can’t get jobs. I’m still with my mom — a lot of us is getting stuck,” she said. Working with YASP gives her hope. YASP organizers have been taking their stories to high schools and colleges across the region, and to lawmakers. They are compiling an anthology of poetry written by teen prisoners and have made a documentary to spread the word. Recently, they visited YouthBuild, a school with a number of students who have been locked up. By the end of the visit, they had signed up one or two new volunteers and maybe even changed a few minds. YASP Is A Facilitator Lasting changes to the prison system seem far off, but the effect of YASP's work in and outside the jails is immediate. For example, former prisoner Zekey Simmons recently landed a job with the help of YASP. Although he just got out of prison, Simmons is spending as many Saturdays as possible back in, as a YASP volunteer. “I just want to help somebody. I know it’s cliché, ‘If you can help just one person,’" he said. “But one life is a whole lot.” This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com.