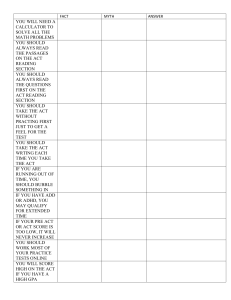

George 1 Maren George Nadja Ben Khelifa Myth in Contemporary Culture (17323) 22 November 2016 Dragons and their Cultural Function “Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon” (Chesterton 130). What G.K Chesterton describes here is very much related to what will be the subject matter of this paper. He describes the dragon presented in an allegory which gives rise to a powerful moral. In that he describes the main attribute of a fantastic myth (Dant 18-19). The myth of the dragon is by far not a new development and how it has been reused in contemporary culture will be the main focus of my analysis. Even more important are the characteristics that almost all of the dragon myths have in common. Myth tends to take an increasingly metaphorical form if it addresses something complex (Dant 23). This is especially the case when the stories of dragons and their slayers are being told. My analysis will draw on the theories of Roland Barthes and Adorno and Horkheimer to demonstrate how the dragon is used by myth to represent social challenges in a simplifying manner. George 2 1. Theories of Myth: Roland Barthes & Adorno and Horkheimer For the purpose of my analysis I will draw on two different perceptions of myth, entailing two distinct approaches of decomposing myth to its underlying cultural function. It is this ultimate function which connects Roland Barthes’ theory of myth with the one of Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer. Both of them see myth as something used by mankind to, as Barthes indicates, “transform history into nature” (154) and therefore to confirm “the everlastingness of the factual” (Adorno and Horkheimer 27). Myth thereby gives one the comforting illusion of dominating nature (Adorno and Horkheimer 27). Barthes as well as Adorno and Horkheimer discloses the hidden function of myth in order to place it in the focus of his cultural critique. The aim of this paper, however, is an analysis of contemporary cultural phenomena and not an attempt to judge or demonstrate its deficiencies. Subsequently, the two positions of understanding myth will be explained, in order to provide the tools for approaching the dragon myth. The starting point of Barthes theory is the treatment of myth as a type of speech, a “second-order semiological system” which is build upon the first language system (see fig. 1), as described by Ferdinand de Saussure (Barthes 137-138). Fig. 1. Myth as a semiological system. ; Brian Davis ; faslanyc.blogspot.de, 22 Nov. 2016, faslanyc.blogspot.de/2010_09_01_archive.html. This entails the universality of the mythical message; everything transmitted through discourse can be used by myth, regardless of its medium. Myth has the capability to utilize George 3 messages conveyed through oral speech just as well as those conveyed through writing, pictures or film. Barthes argues that myth turns messages into objects and thus cannot be defined by the message itself or its medium (131-132). Myth does not belong to language but it exists next to it and analyzing myth therefore means to resort to semiology. In semiology signification is studied apart from content, just as myth needs to be separated into the language object and what myth wants it to signify (Barthes 134). The objectification of the message is achieved by reducing the sign of the linguistic system to a signifier for the secondorder system that is myth. During this process, the original meaning of the linguistic sign is suppressed to enable its transformation into the signifier of mythological system, which is then termed form. Myth then uses the sign, reduced to form, to convey its signified which Barthes calls the concept. Form signifies concept and the result of merging the two is the signification, the sign of the second order system (Barthes 139-140). As opposed to the relationship of the signifier and signified in the linguistic system, the relationship between form and concept is not arbitrary (Barthes 150). An example of this relation is the equestrian sport, especially in advertisement, to signify a superior luxury. Equestrianism as a sign of the linguistic system is full of meaning; it has a history and therefore is a complete representation which is already satisfactory. In the process of turning into form it is distorted and reduced to a vessel for myth. The poster advertising for an extravagant watch depicting a rider and his horse in fine leather tack, has little to do with the actual sport. In this case equestrianism is used to feed the mythical concept of superiority. The signification works since equestrianism has a history of being the sport of the wealthy, the recreation of kings and other noble men. This is where the interface between Barthes and Adorno and Horkheimer’s theory emerges. The historical motivation of myth is turned into a natural link. The artificial signification it is declared as nature and a matter of fact. The truth, however, is that it represents the subjective knowledge of reality arisen from the values of a George 4 culture over the course of history (Barthes 154-156; 168). Every myth has a historical foundation and it is consequently history which changes and influences them (Barthes 143). Whilst Adorno and Horkheimer arrive at a similar conclusion, their approach to myth is defined by reading it in form of a complete system, employed by humans to illuminate the world. They argue that the basic pattern of myth was the interpretation of the inanimate forces of nature as powers of the supernatural. In creating these supernatural beings to explain the world, mankind produced a fictional force which started to control its creators through fear. Myth seen in this way does not give humans control over nature but only the illusion of an influence if they behave according to the rules they themselves have created, but fail to recognize as their own. As a result, myth lets people suffer in fear of the hostility of their imaginary creation (Adorno and Horkheimer 5-7). Even though the era of Enlightenment also seeks to provide explanations for nature, it always aimed at defying myth, by substituting the supernatural with science (Adorno and Horkheimer 3). What was once controlled by religion is now dominated by technology. Enlightenment introduced a new kind of knowledge defined by rationality (Dant 23-24). It replaced the old mythologies yet Enlightenment then turned itself into myth, as rationality started to dictate thinking without questioning its legitimacy. Rationality turns the individual into a subdued being by a system which is as totalitarian as myth (Dant 25). Just like the magic propagated by myth, science installs rules and ultimately renders nature to be predetermined, thus dominates both humans and nature (Adorno and Horkheimer 9-10). Science has become problematic, since, like myth, it reduces its subjects to objects, to be analyzed with the tools it provides. The producer of science, society, is not questioned. Society is ruled by science through the attempt of fixing its issues and condensing it into facts. That way, the essential nature of society along with the influence of history is disregarded, letting myth survive in the legitimization of scientific thinking (Dant 25). George 5 2. The Dragon Myth The dragon is a mythical creature that can be found in almost every culture, although the Asian and European variants are probably the most famous. Since different myths might mention different types of dragons with various attributes and characteristics, it is difficult to define a common cultural understanding of what constitutes a dragon (amnh.org). Nonetheless, when looking at the history of the dragon myth in Europe, what seems to be the common denominator of all these versions is not the dragon but its purpose. The creature signifies a challenge. Beowulf recorded in about 1000 and therefore presenting the first recorded instance of the dragon slayer motive in European culture, employed the dragon as the final heroic challenge (Cambria 40). The Old Norse Thidreksaga, written down around 1250, tells the tale of Siegfried’s youth, a dragon slayer, who remained a famous fictional figure. He passed the challenge of defeating the dragon despite the expectations of his malicious foster father (Rank 44). Even more interesting than the dragon myth being used to signify challenges is the fact that these challenges appear to be related to some form of social complication. The challenge of the dragon does not only produce heroes but it simplifies the solving of a more complex social issue. While Beowulf’s fight against the dragon has been argued to also be a fight against the collapse of a troubled society or even entire culture (Cambria 42), Siegfried’s victory over the dragon elevates him in social hierarchy to claim his rightful position besides kings and princesses (Rank 43-44). The dragon, despite being a monster, eventually creates hope, for it can be killed. However, the question remains whether the dragon myth is still relevant in contemporary culture today, hundreds of years later, after the Enlightenment’s attempts of ruling out magic. George 6 A closer look into recent film productions featuring dragons shows that the myth of the dragon as a social challenge remains relevant until today. The main objective of my analysis will be the 2010 DreamWorks Animation movie “How to Train your Dragon”. It serves as a representative example for the use of the dragon myth in contemporary culture. The movie displays the story of a young Viking named Hicks who struggles to find his standing in society. Hicks lacks certain traits such as physical strength and aggressiveness, which would qualify him as an adequate successor to his father, the clan leader. As a result he fails to meet the clans’ expectations and has to live as a social outcast. In order to redeem his reputation he attempts to kill a rare dragon species, which has been regularly attacking his village but could not be defeated yet. Despite managing to injure the dragon enough to turn him into easy prey, he decides to gain his trust instead and tames the dragon he names Toothless. After a final battle against the evil, manipulating alpha dragon, the clan and, most importantly, Hicks father recognize the young Viking as the hero he really is. The clan starts to build a friendly relationship with the dragons they have mistreated as monsters for so long. The dragon in this case is isolated from his mythical history, since it does not resemble a monster anymore. As it nevertheless has a history of signifying challenges, myth renews itself by claiming the dragon as a redefined language object, to suit the taste of a new society. The movie plays with the original notion of the dragon as a monster when it introduces the evil alpha dragon as the final enemy, yet it is Toothless, the new interpretation of the dragon, who kills him. Toothless thereby redeems the reputation of his whole species and strengthens the redefined version of the dragon, considered more appropriate for the young audience of its time. Over the course of the movie, the friendly dragon is turned into form for the concept of a social challenge. Although the concept never represents a fixed and definable idea, it is still powerful in its composition of vagueness and flexible associations (Barthes 140-142). Barthes also describes the concept as introducing “less reality than a George 7 certain knowledge of reality” (142). The knowledge of reality in this case is that a dragon always constitutes the opportunity a hero needs in order to turn his fate around and thus provides the motive for the combination of form and concept. The dragon is used to signify a social challenge because of the possibility to draw an analogy between the two. Toothless enables the signification which contains Hicks fight to fit into a society seemingly not made for everyone and what later develops into a clash between the mindset of two generations. In this way the dragon is employed by myth to simplify a complex issue. Hicks starts out as an outcast of his own generation and the one of his father. He questions his own identity. He is faced with a lifelong problem on many levels which leaves him no hope for a happy future. The movie is emphasizing these issues clearly and therefore feeds the initial impression of a flawed society that is unable to accept every individual and resistant against change. When Hicks befriends the dragon and accomplishes the challenge, he resolves all of his previous problems and proves the initial impression wrong. The dragon myth here serves as what Barthes understands as a cultural value (172). It supports an attitude towards society which sees it as a functioning system that adapts for everyone. As a centuries old object of myth the dragon has become very powerful since it thus has lost its resistance against myth (Barthes 171) and transports a moral: dragons can be killed; the issues of a whole culture are not as severe as they may seem; there is always a silver lining if one is willing to tackle their own dragons. It is exactly this age old moral, that How to Train your Dragon manages to convey for its audience. Domination over human nature and the social conflicts it produces, as Adorno and Horkheimer described it, is achieved through the process of the dragon myth signification. Toothless and Hicks’ story explains the world naturally; the process of integration is always possible and mankind can master their own nature which stands in the way. For the effect of myth it does not matter that the dragon is an openly fictional creature. The connection George 8 between challenge and dragon is now a preexisting rule of nature, instead of being forced. Humans want to believe that they can defeat their own hostile nature, which they have been separated from by themselves. They want to kill their dragons in order to merge into the comfort of society and to be “free”, even if in reality this alienation from nature confines them (Adorno and Horkheimer 28). The exact same use of the dragon myth that was previously described and its function can be found in other contemporary movies such as James Cameron’s Avatar. Here the dragon needs to be tamed in order for soldier Jake Sully to be accepted into the native tribe of a foreign planet. Further one could examine Pete’s Dragon, a children’s movie, in which a young boy grows up in isolation and thus has problems to find his place in society. What hinders him is not his character or the nature of society. Instead, his issues are personified by his giant dragon friend that holds him back from assimilating into civilized society. 3. Conclusion Both theories of myth introduced in this paper have proven themselves to be applicable to examine the dragon myth in contemporary culture. They managed to provide explanations for myth, as an essential component of human thinking that remained relevant long after the Enlightenment. In the instance of the dragon myth, survival was accomplished due to its adaptation to cultural changes in a culture over the course of history. While the value or moral the myth conveys has not been altered, the dragon as a mythical object was redefined. The vengeful monster that Beowolf needed to face was turned into the smiling character of a children’s movie or the exotic working animal of a faraway planet. Nevertheless, they still display society’s need for creating fictional realities to bring hope in shape of a new generation of dragon slayers. To provide additional insights into the social function of the George 9 dragon myth, one could further conduct a more detailed analysis of the different social troubles that are resolved through the domination of the dragon. It should also be mentioned that the same concept can have many forms (Barthes 143) and that the dragon is not indispensable as an object nor bound only to the concept of a challenge. This circumstance makes it even more remarkable that the dragon myth survived the way it did. No myth is eternal (Barthes 132), yet as long as the dragon myth is alive it may be used to analyze the challenges of the individual in a culture then, now, and in the years to come. George 10 Works Cited Adorno, Theodor W., and Max Horkheimer. Dialectic of Enlightenment. Verso, 1997. Avatar. Directed by James Cameron, Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation, 2009. Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. Vintage, 2009. Cambria, Errol. The Esoteric Codex: Anglo-Saxon Paganism. lulu.com, 2015. Chesterton, Gilbert Keith. Tremendous Trifles. Dodd, Mead, 1913. Dant, Tim. Critical Social Theory: Culture, Society and Critique. Sage Publications, 2003. “Dragons - Creatures of Power.“ American Museum of Natural History, 10 Nov. 2016, www.amnh.org/exhibitions/mythic-creatures/dragons-creatures-of-power. How to Train Your Dragon. Directed by Dean DeBlois and Chris Sanders, DreamWorks Animation, 2010. Pete's Dragon. Directed by David Lowery, Walt Disney Productions, 2016. Rank, Otto. “The Myth of the Birth of the Hero.” In Quest of the Hero. edited by Robert A. Segal, Princeton University Press, 1990, pp. 3-88.