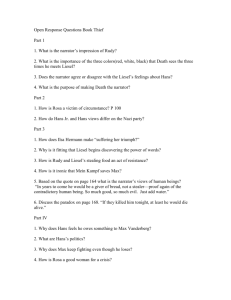

The Book Thief (review) Deborah Stevenson Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books, Volume 59, Number 9, May 2006, pp. 389-390 (Review) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/bcc.2006.0355 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/197387 [ Access provided at 24 Oct 2020 01:34 GMT from Western Libraries ] May 2006 • 389 The Big Picture The Book Thief by Markus Zusak Last year saw the U.S. publication of the inventive and humane I Am the Messenger (BCCB 1/05) by this Australian author; now he’s turned his gifted pen to the daunting yet oft-treated subject of Germany during World War II, and the result is a book of heartbreaking grief and tenderness that earns every page of its substantial length. Its focus is Liesel Meminger (“one of those perpetual survivors—an expert at being left behind”), nine at the start of the story in 1939, and its narrator is death. Zusak’s powerful yet nimble writing ensures this conceit never becomes a gimmick, staying a penetrating yet poignant perspective; our narrator is never overly personified, but even he tires of the needless extra labors humanity gleefully throws his way, complaining about the Third Reich because “in all honesty . . . I was still getting over Stalin, in Russia.” He describes his liberation of often tortured souls in tones ranging from the matter-of-fact to the merciful, reserving his pity for the survivors, as in the case of Liesel. The narrator first spots Liesel when he takes her brother, as her family travels on a train to Munich where the children are to be put into foster care (their mother, a Communist, hopes to save her children from the fate she anticipates under Hitler); at her brother’s graveside she begins her career as a book thief, pocketing The Grave-Digger’s Handbook. Despite her losses, she grows to love her gentle foster father, Hans Hubermann, and to tolerate her hot-tempered foster mother, who addresses Liesel only in foul-mouthed imprecations (Saumensch, “swine,” being a favorite), and she also makes a firm friend in flashy but loyal classmate Rudy Steiner. The patient tutelage of Hans, himself a laboring reader, helps Liesel learn to read by helping her sort out the world of her book’s words, the book that is her only connection, save her nightmares, to her lost brother. She finds power in words, especially words in the books that she steals—from the bottom of a conflagration of unacceptable books the townspeople are burning, from the library of the mayor’s wife. Her family is committing a bigger crime—they are hiding a Jew, the son of the man who saved Hans’ life in the first World War. They secrete Max in the basement, where he becomes reliant on Liesel for his small glimpses of the outside world, and she in turn becomes reliant on him as something precious that has been saved where others have been lost. The book uses its length effectively; its duration is not oppressive, but it’s a significant and noticeable part of the reading experience, a stretch that operates to remind readers of the exhausting length of Liesel’s own experience in a Germany of danger, disorder, and death. The length also permits the intense drama to be enriched by strongly individual characters, such as athletic Rudy, famous in the neighborhood for having blacked himself up as Jesse Owens and run around the 390 • The Bulletin playing field imagining himself to be an Olympic medalist, and Rosa Hubermann, a “good woman for a crisis,” legendary for her scorn and profanity and utterly invested in her husband and foster daughter. Texture also comes from the complicated networks of human connection that shuffle the cards of chance, allowing some to escape death in one instance only to walk into his grasp elsewhere, but that also bring us together in strange and sometimes unappreciated ways. The result is a book that manages a poignant specific focus on major history but also moves beyond the specific, using the war as a lens to examine the destruction we wreak upon ourselves as a species and the significance of even seemingly small redemptions. It keeps its feet on the YA ground, realizing Liesel’s world accessibly, to make its sliver of recurrent, pounding tragedy in a world overburdened with tragedies all the more lacerating, to give human goodness a grace the more luminous for its homeliness, and to give the power of words even amid darkness a momentous, indelible tribute. It’s a book of greatness. (See review, p. 430, for imprint information.) Deborah Stevenson, Editor New Books for Children and Young People Aruego, Jose The Last Laugh; written and illus. by Jose Aruego and Ariane Dewey. Dial, 2006 24p ISBN 0-8037-3093-4 $12.99 R 4-7 yrs One can tell from the glint in this snake’s eyes that he’s up to no good. First he scares a stork, then a gopher, a family full of opossums, and finally a duck, with a not-so-nice “Hiss!” and a downright mean “Hee . . . Hee . . . ” at his success. Serpent is changed, however, when the poor startled duck flies right down the snake’s throat, and now all the snake can emit is a “Quack!”, which brings ridicule from his snake peers and the unwanted attention of a crowd of ducks. Happily, the swallowed duck emerges from the snake’s mouth unharmed; distracted by the departure of his tormentors, the overwhelmed snake does not notice the duck sneaking up behind him to scare him with a final mighty “QUACK!” The nearly wordless book is “dedicated to bullies everywhere,” and though the only remedy it proposes is payback, it offers an extended giggle-worthy joke that audiences will be glad to be in on. The visual telling of the gag is successful due to the placing of vibrantly hued, colorfully patterned animals against a simple white background and the use of comic-strip-style panels to relate the narrative. Simple lines, visual cues implying movement, and animated expressions combine to keep the viewer engaged, and the book is sure to be a hit with those who relished Feiffer’s similarly streamlined joke about animal sounds, Bark, George (BCCB 11/99). This is one punchline kids won’t mind rediscovering again and again. MH