FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS pAPER - Human Ecology Forum

advertisement

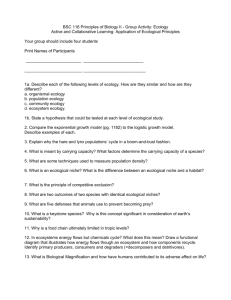

The Australian National University •••• e Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies Ecological sustainability, deep environmental ethics and Tao: a preliminary conjunction Fundamental Questions Paper No.4 David Bennett Department of Philosophy University of Adelaide 1990 FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS pAPER Ecological sustainability, deep environmental ethics and Tao: a preliminary conjunction Fundamental Questions Paper No.4 David Bennett Department of Philosophy University of Adelaide 1990 ISBN 0 86740 389 6 This paper is an outcome of the theme area of societal values and ecological sustainability of the Fundamental Questions Program. Other papers in this theme area include: No.3 The evolution of societal values compatible with ecological sustainability A. J . D. Bellett No.5. Values for sustainability: the necessity of transcendence and sacred realms. P. Cock No.6. Environmental management and the political philosophy of trust. G. McDonnell No.7. Aborigines, values and the environment. K. Palmer No . 8. How green was my Mallee: changing Australian attitudes to their land. B . Roberts Work in this theme area was assisted by financial support from the Howard Norman Trust. Papers in the Fundamental Questions Paper series arise from Part 2 of the Fundamental Questions Program at CRES. The main outcome of Part 1 of the program is presented in Our biosphere under threat: ecological realities and Australian opportunities (S.Boyden, S.Dovers and M.Shirlow, Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1990). The Fundamental Questions Program seeks to engender and inform public discussion of the implications for Australian society of the need for long-term ecological sustainability. Ecological sustainability, deep environmental ethics and Tao: a preliminary conjunction The fundamental questions that I wish to explore are: ' What are the relationships among ecological sustainability, deep environmental ethics and Tao?' and 'What can Tao offer Western approaches to ecological sustainability?' It might be asked, 'Why ask these particular questions? ' Why is it assumed that there is some relationship among ecological sustainability, deep environmental ethics and Tao? Behind the fund amental questions there are assumptions that need to be brought to light that will help answer all the above questions. The first assumption is that the fundamental relationship among these elements is founded on values . The catch phrase of 'ecological sustainability • and the cry for environmental awareness and concern are moving up the political, social and ethical agendas of individuals, peoples, cultures and nation-states around the globe. Ecological sustainability is being accorded significant value. The reasons for this are diverse, such as: perspective of the species has to overcome shortterm interests of existing individuals. For instance, environmentalists find it amazing that wood chippers fail to see that the jobs they are fighting so hard to keep now will be gone with the forest in one, two or five years· time, when they have clear felled the forest. For the most part, industrialized societies take short-term (and retrospective) patch and repair approaches to environmental damage rather than the long-term (and foresighted) prevention of damage. Fish disappear from the Thames, the Hudson, or the Seine and a concerted effort reverses the rot to the extent that fish reinhabit it and pollution levels are lowered. But if present and future generations of humans, of other species and of environmental items and systems are considered desirable, that is valuable, then their survival is to be taken account of and encouraged. Humanity, especially in the developed nations , such as Australia, has pursued economic growth to the exclusion of almost all else. The sort of over-indulgent economic pursuit that lead Aldo Leopold, the American ecosaint, to say, 'I believe that many of the economic forces inside the modern body-politic are pathogenic in respect to harmony with land • (Leopold 1953, 153). The environment and ecological cycles and relationships have been sacrificed for economic gain. As Richard Eckersley of CSIRO has stated this: • to maintain essential ecological processes and life-support systems; • to preserve genetic diversity; • to ensure the sustainable utilisation of species and ecosystems; • to maintain and enhance environmental qualities (Endangered Species Advisory Committee 1989, 7) environmental problems have a common source. ... It is not the pursuit of economic growth and an ever-increasing material standard of living. It is the pursuit of these things to the virtual exclusion of all else. We are putting too much emphasis on wealth generation and not enough on its distribution and conservation. but an underlying motivation is simply identified survival. Humanity has threatened its own existence as well as the existence of the rest of the environment. Humans and the environment need not survive, of course. The anthropocentric survival argument, that is, appealing to human survival should be a very strong argument, but it is not. It is weak, because the long-term survival 1 The links between economic growth and environmental degradation are clear. Japan's striking success in becoming one of the world's biggest economies has come at the price of becoming also one of the world's biggest polluters (Eckersley 1988, 9) Common Future is not compatible with ecological sustainability. As it is conceived, it is incompatible with the flourishing of other species, unless they are considered part of 'future generations' and 'the world's poor' (which is doubtful), and with reduction of human interference. Although the idea of integrated and sustainable development has been floated, Ecological sustainability means integrating ensustainable means sustainable in relation to vironmental considerations with economic humans. The sustainable development policy growth or replacing non-environmentally acdoes not lower human impact on the environment, countable economic considerations with ones consider long-term viability of other species, nor which are. The primary value of ecological susinclude the requirements of non-humans into containability is that without it there is no economic siderations of meeting the requirements of sustainability. The principle behind the shift humans. The environment remains a human arfrom economic pursuit to ecological sustifact and is not valued in and of itself. Ecologitainability is an ecological one and can be easily cal sustainability is defined solely in terms of spelt out in terms of habitat destruction. Habitat human sustainability rather than environmental destruction is the greatest threat to species sursustainability. vival, regardless of the species. Even the most Thus the first relationship among ecological adaptive species have tolerance limits. Without sustainability, deeper environmental ethics and the integration of ecological sustainability with Tao is a common search for a way of according economic sustainability, there is no foundation greater or substantial value to the environment for human life or for other species. and environmental considerations . The Perhaps the most often quoted source for the dominant paradigm for valuing the environintegration of economic and ecological susment, which is to consider it as an instrument for tainability is the World Commission On Enhuman use or a human artifact, has proven unvironment and Development's report Our satisfactory. Indeed it has proven so unsatisfacCommon Future, or as it is commonly known the tory that it has produced environmental crisis Brundtland Report after Ms Gro Harlem and has become a case of 'when-all-else-failsBrundtland, the Norwegian Prime Minister who read-the-instructions'. When all or many of our headed the Commission. The Brundtland Commodifications of nature fail, it is time to read the mission uses 'sustainable development', instead instructions. And the instructions that come of economic sustainability, which it defines as with nature indicate that when a species over' development that meets the needs of the present fills and overruns its niche, when a species overwithout compromising the ability of future utilises its resource base, when a species lives generations to meet their own needs' (World beyond its environmental capital, it must move Commission 1987, 43). In a shortfall attempt on or die. to designate the value accorded to ecological Ecological sustainability recognises a sustainability, the Commission states that susnatural order. The manipulation of nature tainable development contains two concepts: (ecological systems) under the banner of ecological sustainability recognises the neces• the concept of 'needs', in particular the sity to maintain the system while drawing vital essential needs of the world's poor, to which needs from it. Natural limits are recognised. overriding priority should be given; and There are only finite quantities of nonrenewable • the idea of limitations imposed by the state resources such as the fossil fuels , coal and of technology and social organization on the petroleum, available, and once they are depleted environment's ability to meet present and they cannot be replaced (not, at least, in human future needs (World Commission 1987, 43) time spans). For example, consider what many hold to be the energy hope for the future to This attempt falls short because it still places replace the depleted fossil fuels nuclear energy: economic considerations ahead of ecological Given current practices [nuclear energy] considerations instead of integrating them. The too is a non-renewable resource. Even at purportedly integrated sustainability of Our 2 current rates of consumption there are only enough recoverable uranium reserves to last between 37 and 70 years; and this providing we are willing to live with the occasional disasterJ the accumulation of radioactive wastes, and the resultant environmental damage. (Flannery and Conlon 1989, 150, 152) clarify this last point, the extinction of any given species is inevitable, but humans need not bring this upon themselves or accelerate the process by destroying the environment, and therefore, their resource base. Ecological sustainability is more than a delaying tactic; it is planned and managed strategic use of ecological principles and processes to maintain a constant supply, rather than merely conserve a constantly decreasing supply. It is preservation plus prolonged, controlled, that is, sustainable use. It is modification without devastation. Ecological sustainability as thus far defined has the following embedded assumptions: While renewable resources have the potential for replacement, they cannot be consumed faster than they can regenerate, if they are to be ecologically sustainable. Although other resources, such as com, rice and other cereals, cattle, fish and timber, renew themselves and can be regularly cropped to provide the food, clothing and shelter essential to human survival, it is not so clearly realised that these resources are renewable only to the extent that their use is rationally planned and managed. There are limits to the extent to which we can draw on these resources; if these limits are exceeded, this will destroy the capacity of resource renewal. Unfortunately, most current utilisation of aquatic animals, of the wild plants and animals of the land, of forest and of grazing lands is not sustainable. For example, 'More than 11 million hectares offorest are destroyed yearly ' (Commission For The Future 1989, 5) and 6 million hectares tum into desert yearly (Commission For The Future 1989, 5). At the current cutting rates virtually all of South America, Africa and substantial portions of Asia will be deforested by 2020 (Hemenway 1986, 3). As another example, according to Geoff Kirkwood, CSIRO Principal Research Scientist in the division of fisheries, 'In world fisheries generally there is a push to overexploitation. The southern blue fin tuna is one of the worst examples' (Austin 1989, 40). The only safe catch limit would be zero, 'because a fisheries resource can progress from being unexploited to fully or overexploited before basic population dynamics information can be gathered.' (Austin 1989, 40) , therefore a sustainable catch limit is the single greatest challenge facing fishery industries. Ecological sustainability is more than the conservation of resources. Conservation is the rationing or stretching of resources to delay the inevitable or foreseeable end of them. At worst, sustainability places the end beyond sight and , at best, makes the inevitable a function of unaided ecological processes, rather than bringing it about as a result of human hubris in attempting to contravene ecological processes. To 1. that there are discoverable ecological principles that can be followed; 2. that there is greater value in following them rather than opposing or attempting to contravene them by manipulating them; and 3. that following these ecological principles at least provides the potential for sufficient renewable resources. These assumptions are the assumptions of Tao. Tao combines a complex of natural principles and methods with guiding ethical forms, with no imposed separation of fact and value. 'The word tao consists of one element meaning a head and another meaning to run. It means that on which something or someone goes [that by which a thing becomes what it is], a path or road, later extended to mean "method", "principle" ... ' (Chan 1963, 6). The great or overarching Tao is a comprehensive source of natural activity; it encapsulates a framework of forms or principles, principles of natural order, both metaphysical and moral. It comprises both dynamic principles (or evolving 'laws') of nature and axiological principles guiding conduct. In this representation it invites comparison with Plato's forms. But to see overarching Tao as an axiological ontology, after the pattern of Plato's Form theory, would be to import unwarranted Western assumptions. Though Tao is a 'great form' , and there is no doubt room in the generous object framework for other forms, main Platonic forms such as Beauty, Truth and Goodness do not feature in the Tao-te Ching, the principle text of Taoism. Tao as an informing source is summed up in such phrases as 'The or~ginal of everything and out 3 of which all arises.' Tao as combined governing principle and source is summed up in such phrases as 'the ancestor and mother of all things' . Tao supplies both the material source and the form, the genetic coding, for existence. Tao is the way of the universe. In other words, it is the ecological principles to be discovered and followed. The value of following nature rather than opposing it or attempting to manipulate it is in achieving sustainability and hopefully an adequacy__of supply, while simultaneously keeping the ecological systems, cycles and processes intact. Tao is not supernatural, and it does not transcend natural things in the fashion of Western supernatural religions. Tao orders and reflects nature. As to the status of the principles, standard Western categorisations are exceeded. These principles are not transcendent, governing things externally, but are, so to speak, self-supplying. A major difference between ecological sustainability and Tao is that ecological principles are normally considered to be external to the organisms that they affect, Tao principles are both external and internal to the things that they affect. There is a sense of identification between the individual tao and the great overarching Tao that supplies the principles that an individual may follow. One Tao metaphor that expresses this is the image of the chef cutting meat with the grain of the meat and along the bone rather than across them. The chef never dulls his/her knife and never attempts to cut the bone. But this means that some ways of cutting meat are precluded, such as dicing and chopping into mince. The image is particularly apt in these times of wood chipping. In contrast to European political thought of the mainstream Hobbes-Locke strain, where the state-of-nature is one of chaos or extreme disorder, the Taoist state-of-nature is one of order. A main assumption of Western thought, that political order must be imposed by regulation on an unruly state-of-nature, is thus undercut. A separate imposed political order is not required; that idea rests on mistaken assumptions. Politics can, and should, follow nature. Science and politics can and should be blended, not sharply separated in the typical Western fashion, where nature is taken to exclude value. Nature presumes value. Nature is already in order as it normally is, through a unity in diversity which involves a normative component- a principle or recipe for 4 how things 'should' be as well as how they are integrally. Values are built into the environment, an integral part of the way of things. By following the values of Tao one enters and comes into contact with the whole environment and into unity with the environment. Tao is a description of how things are and a prescription of how to act in accord with the way they are. According to Taoism then, by contrast with dominant Western thought which sees the world as extensional, mechanistic and value-neutral (except for human cargo), the world is both intensional and value-infused. These features extend not merely to the whole, but to components which go into composing the greater whole. These have their ways, which are integrated into the greater way. The overarching Tao combines many individual ones, lesser or lower case taos, within it. Such a lesser tao, of an individual, system or whatever, is what makes a thing what it is properly, a coursed or directed path. A tao is a sourced directed object; it is thus a type of object, a dynamic item, which can be represented by a pair comprising a recipe, program or form and a direction or goal-orientation. Accordingly, an individual or local tao (or form) resembles one of Aristotle's individual forms as coupled with a telos, which comprises a normative directive. For both Aristotle and Tao there is, in effect, an 'invisible hand' at work. Taoism holds that there is no genuine problem of plenitude; things are not scarce, there is an abundant outpouring from nature. There is scarcity only because of violations of the requirements of Tao (rather as some claim there is food scarcity even now, with present gigantic human populations, only because of politico-economic mismanagement). Tao will serve to restore plenitude (Chan 1963,77). Rather than a collection of scarce resources, Nature is represented as a virtually infinite storehouse of boundless wealth. It seems plain, however, that Tao did not face environmental problems such as those of too many people and of incremental resource degradation. Tao texts say little about soil degradation and deforestation, long major environmental problems in China. By contrast, in the West, Plato was properly concerned about deforestation in Greece. Nor does Taoism have much to offer directly on major contemporary issues of animal liberation~ species loss, urban disgustification, and so forth, though some of the problems are hardly new. Historic Taoism, too, was a product of its times, and it adjusted to what were seen as problems. With respect of the abundance of nature, in addition to not recognising the overpopulation problem, Tao also held a principle of frugality. Frugality is not impoverishment, but a renunciation of excess. Needs are met adequately without deprivation or excess. This is achieved through voluntary simplicity (my choice of phrase, not Taoism's). Tao offers a deep form of voluntary simplicity. Voluntary simplicity can initially be explained through its two obvious components: simplicity, and its voluntary adoption. Simplicity connects with, and is often equated with frugality, as elaborated in Taoism. But whether or not simplicity is obtained from frugality or other Taoist virtues, it plays a direct and important part in the theory, and is in fact modelled , like its metaphysical counterpart, the unconceptualised Whole, by the uncarved block, a central Gestalt of the theory. The block symbolises unity, simplicity and naturalness not spoiled by artifice, metaphysically the wholeness and unity of Tao before conceptual carving, and ethically the wholesome straightforward non-devious life under Te, the 'simple life that is free from cunning and cleverness, is not devoted to the pursuit of profit or marked by hypocritical humanity and righteousness, but is characterised by plainness, tranquillity, and purity' (Chan 1963, 14). Te is the complementary principle to Tao. Te can be translated as virtue, but virtue is misleading because Te is the vital power that belongs to a follower of Tao who is in harmony with nature's changes. If Tao is the Way, then Te is the virtue or power gained by following the Way. As to voluntariness, people have a choice of selecting the way of Tao rather than one of the deviant ways. It is a choice of recipes frugal vs. excess, relatedness vs. non-relatedness, tall poppies vs. not daring to be ahead. But one does not attempt to force one's way onto the correct path. To hyperactively seek the path is a deviation in itself. It is deontic to speak of a requirement to find the correct path. This is a connecting principle uniting ecological sustainability, deep environmental ethics and Tao. Ecological sustainability on its ecological side seeks to identify ecological principles, cycles, or metaphorically the instructions that come with the environment, having identified them, the sustainability side seeks to fol- 5 low them, instead of opposing them and by opposing end them. There is a natural order to be discovered and obeyed or at least not opposed. Ecological systems are complex so it is not easy to discover precisely how they work, but it is easy enough to disrupt them and discover how they do not work. Tao offers the notion of respectful use. Dominant Western traditions have offered the false choice between respectful nonuse and disrespectful use. It has been an all or none situation in which environmental items have either been available for almost unrestricted use with economic considerations being the major or only restriction on use, or environmental items have been protected and all use prohibited. In following nature some current uses would continue, such as tourism at Uluru, although perhaps on a more restricted basis, and some current prohibitions would remain, for example, gravel extraction from Uluru would be out of the question. Respectful uses would be the hallmark free-range egg production instead of battery production. To follow the instructions that come with nature requires fundamental changes and for changes to be of any consequence, they must be at the basic philosophical level, thus the need for a deep environmental philosophy. The suggested change 'to follow Nature' can be drawn from the Cynics; from Aldo Leopold, who said, 'A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise' (Leopold 1966, 262); or Tao. In part, Tao constitutes the principles, cycles, or the set of instructions, but with the proviso that Tao instructions are more caveats than prescriptions, that is, ignoring them is more like self-inflicting a wound than transgressing a moral 'ought'. If this is so, then what is the relationship between Tao and deep environmental ethics? One explanation of a relationship, and the one that first inspired me to become interested in the environmental aspects of Tao, is given by Deep Ecology, which is the most widely known of the deep environmental ethics. Deep Ecology combines practical prescriptions with normative principles. Deep Ecology draws on Tao and acts as a practical platform for transferring the insights and wisdom of Tao to a program of ecological sustainability without the necessity of adopting Tao as a religion in part or in whole, although adopting Tao as a religion is not precluded. Christianity Deep Ecology is a way of interpreting the instructions that come with nature. Deep Ecology is a deep environmental movement founded in Europe and adopted in Australia and elsewhere, largely through the influence of advocates like the Norwegian philosopher, Arne Naess, who coined the tenn 'Deep Ecology' and Bill Devall, a US West Coast doyen of Deep Ecology, both of whom have visited Australia on several occasions. Although many have eagerly embraced Deep Ecology world-wide, it has also attracted many critics. Its philosophical core is less than rigourous intentionally so. The philosophical core of Deep Ecology is called ecosophy. Devall and George Sessions, another US West Coast advocate of Deep Ecology, have defined ecosophy as 'a normative system which includes both norms (or basic values) and factual hypotheses' (Devall and Sessions 1985, 226). To blend facts and values is against the former mainstream of Western philosophy, which since the time of Hume held a rigid fact/value distinction. The philosophical core of Deep Ecology, therefore, presents a different ethical footing rather than an extension of dominant systems. It is a different order of ethic rather than a variation on a theme. Ecosophy is a combination of 'ecos ' meaning 'household' in the ancient Greek (and is the same root for 'economics') and 'sophia' meaning 'wisdom'. Figuratively, ecosophy is the wisdom of living in harmony with nature, that is one's household in the broadest sense. Ecosophy involves a shift from mere science to wisdom. Naess also coined the term 'ecosophy'. Deep Ecology is an elaboration of the position that natural things other than humans have value in themselves and that that value sometimes exceeds the value of or had by humans. In other words, Deep Ecology rejects both the ' Sole Value Assumption' and the 'Greater Value Assumption'. The 'Sole Value Assumption' is the assumption that humans and human projects are the only items of value. The 'Greater Value Assumption' is the assumption that humans and human projects always out value other considerations and the value of other things. Deep positions are set apart from both shallow and intennediate positions by this latter rejection. Shallow positions maintain both assumptions and intermediate positions reject the 'Sole Value Assumption', but not the 'Greater Value Assumption'. Deep Ecology is not a science, despite the T ao Philosophy l:und;uncnlal pu.: n1 1S ~ S j Direc1ion of k>CICi.l derivation 1 Pro\ctical decisions Practical situations with coocrerc: decisions Level 3 f=::.:=:::::::;:=====:::E:J Level 4 suggestion in the name. 'Deep Ecology is a normative and policy- and lifestyle-oriented theory' (Sylvan 1985, 43). Like the science of ecology, which deals with the relationships between organisms and their environments, Deep Ecology is concerned with the place of organisms in their environment, but it is bound up with value judgments about the organisms, their environments, and the relationships between them and with the wisdom of living by the principles revealed by ecology ·and not as with the science of ecology with doing experiments that reveal the principles. In a sense, Deep Ecology uses ecology to overcome the embarrassment of science at not being able to convert knowledge into wisdom and state what is most needed - an appreciation of how to value the environment and ecological relationships. Deep Ecology has four levels (see figure). On the first level are the sources of the inspirations, insights, and intuitions of the movement. These may be Christian, philosophical, Taoist, or other sources. On the second level is the platform . The platfonn consists of principles or departure formulations derived from level one. On the third level are generalised hypotheses, that is the level of strategic planning. These are generalised ways of behaving towards the environment. The fourth level is the level of actions, that is the level of tactical execution. These are specific actions in specific cases. If the slogan, 'Think globally; act locally', is applied to these levels, then level three is the global level and level four is the local level. Only at level two is there a consensus, and here the consensus is only a consensus of the intuitions of the principles and not on their exact formulations. Latitude is left for specific fo rmulations for specific circumstances or bioregions. Thus Deep Ecology is a loosely- 6 knit and open-ended pluralistic movement. Considering that Tao is one possible source for Deep Ecology, it is not astonishing that some aspects of Deep Ecology resemble Tao and that Deep Ecology embraces Taoist elements in it, although these elements may have been modified for Western consumption. Appendix 1 gives some idea of the range of similarities between Deep Ecology and Taoism. For present purposes, only a few elements that relate to Taoism, Deep Ecology and ecological sustainability will be considered. It is obvious from the description of Deep Ecology that it promotes a philosophical core that in tum promotes ecological sustainability. Deep Ecology includes in its platform the notions of identification with the environment through self-realization, voluntary simplicity, and lower human population. The first two elements may have been derived from Tao, but the third is not. Self-realization is environmental selfrealization. Thus self is realized by seeking possibilities within the ecological context rather than simply within self. As the phrase 'ecological self' should make clear, self-realization is not self-aggrandizement of the egotistical sort now practiced. Self-realization is not an environmental glorification and glib justification for an ego-cult. In the words of psychologist, Anna-Marie Taylor 'inner ecology can't be overlooked as part of the total ecology' because ' we are all in continuous interchange with the world as part of the world' psychologically as well as physically (Taylor 1987, 100). This means that the distinction between oneself as the subject and all around oneself as the object is also broken down, but not totally obliterated. Identification with the environment and items in it does not imply that subject and object are identical. The distinction between identification and identity avoids the crude fallacy: ' a is related to b, e.g. sister of b, does not imply that a is identical with b' (Sylvan 1985, 27). With further regard to this breakdown, this also means that the objectification that so often accompanies 'being objective' is discouraged . The individual identifies with their environment and treats it as an extension of self and self as an extension of it, rather than separate, unrelated entities. This identification reflects the Taoist image of the uncarved block. Self-realization is a normative premise. It is not articulated in the same way for everyone. It 7 may be solitude in the wilderness for some and gambolling in a crowded park for others. Whatever the expression of self-realization, its normative v·alue is intrinsic as opposed to instrumental. Self-realization is attempting to recognize the intrinsic value in one's situation as opposed to solely instrumental value. Selfrealization is part of dwelling in situations of inherent value and living a life 'simple in means; rich in ends', in other words quality of life. Against this normative premise it can be argued, as Sylvan does, that self-realization 'is much too experiential. It renders value a feature of those who experience value' (Sylvan 1985, 24). This criticism would imply that any value to be had in dwelling in a situation of inherent value would be value had by the dweller and not shared by the dweller and situation dwelt in. If this is the case, then self-realization becomes a matter of maximizing situations of human intrinsic value, which in tum means maximizing human-centered values, which reduces selfrealization to the same sort of anthropocentrre and chauvinistic principle that it is meant to avoid. However, if the internal/external relations dichotomy is dissolved as in Tao, valuer and valued become as one and some of the force of the criticism is dissipated. 'Self-realization individually and at all collective stages presupposes the accessibility of diverse possibilities for personal growth various activities, and occupations, the utilization of geographical and climatic peculiarities, the exploration of different art forms, broad cultural variation - preservation of diverse cultures' (Naess 1978,4-5). Self-realization is a fulfilment of capacities of the most diverse kinds, as part of the environmental/ecological whole and not as atomic egos. Realizing self, where ''Self' stands for organic wholeness' is, according to Devall and Sessions, the real work of Deep Ecology (Devall and Sessions 1985, 67). Naess has characterized this with reference to ecosophy: The only contribution of ecosophy to these...frameworks is the extension of the concepts of social self...to concepts of ecological self. These are wider concepts. The social relations of self built up through internal, not external, relations to other humans, are complemented with internal relations to non-humans. At the age of two years we already have inter- The slogan carries with it an economic reorganization wrapped in an ideological change. 'The ideological change is mainly that of appreciating life quality (dwelling in situations of inherent value) rather than adhering to an increasingly higher standard ofliving' (Naess and Sessions 1984, 5). This approach to the economic reorganization incorporates a change in attitudes towards what makes life worthwhile. In the words of Robyn Williams, the presenter of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation's Science Show: nal relations to near features of the environment house, clothing, perhaps some plants or animals. The body of a child may get a new home, but the child itself is not exactly the same. It does not yet belong at the new place. Only through a rather natural arrogance humans in our kind of culture tend to set humans apart. The slogan 'Not man apart!' belongs to the most potent within the deep ecological movement. One might add 'Not man in environment!' humans are strictly speaking not separable from 'environment' as something 'outside' with which we only have extrinsic relations (Naess nd, 2-3). we have problems which we can solve. It requires more than the attitudes ... current about what our values might be..The values which are presented are only occasionally to do with the environment, they are concerned basically with the bottom line, they are to do with money. ... The kind of values that deal only with personal disposable income (Williams 1987, 14). By collapsing conventional distinctions and dichotomies, self-realization moves away from , rather than towards egotistical notions of self. By collapsing the internal/external relations distinction, humans are opened to what Naess has called the 'ecological self'. The richness of life, fecundity of reality, and quality of life are explored without reducing experiences to prepackaged symbols from the shelf or to manifestations of material wealth. As examples of this: it is the difference between learning to play a musical instrument and merely switching on a radio; and it is the difference between playing music as a background noise and actively listening to music. Humans count the environment as part of what they are and their possibilities are shaped with regard to environmental factors, rather than in spite of them. Ecological sustainability is enhanced because of the realization as in Tao that oneself is part of the whole, of the uncarved block as it were, and lack of ecological sustainability is tantamount to lack of self-sustainability. Thus self-sustainability becomes identified with ecological sustainability. This argument appears circular, but rather it is cyclic reinforcement. One realization reinforces the other when the connection between the two elements is made. This cycle of description and prescription mirrors ecological cycles. The cycle of Tao of being to nonbeing and nonbeing returning again to being before becoming nonbeing again is like the carbon cycle or the nutrient cycles or any of the other ecological cycles. The idea of voluntary simplicity is embodied in the slogan, 'Simple in means, rich in ends'. Deep Ecology opposes this mentality and the goal of a growth-oriented exploitative economic system. An ecologically sustainable society with an ecologically-sound ethic need not preclude a growth in quality, only the now pervasive dedication to a continual growth in quantity. Deep Ecology supports a steady state· economy which sustains all life, not just human life, with an emphasis on quality of life, rather than material-oriented style of life. That is, richness of experience need not depend on continual economic growth. Indeed, as emphasized previously, resource depletion indicates that a continual economk growth policy will result in an eventual reduction in both quality of life and style of life and that economic growth cannot continue forever. A mentality of continual growth to the exclusion of all else as now practised in industrialized societies is incompatible with the inherent value of all life, with the maintenance of diversity, and it creates excessive human interference. Furthermore, value is assessed on scarcity and commodity (i.e., instrumental) value, 'there is a prestige in vast consumption and waste' (Naess and Sessions 1984, 7). The end product of the current economicgrowth mentality which pushes the notion of 'bigger is better', where bigger means 'bigger urban sprawls, bigger waste dumps, and bigger 8 areas of desertification. Rarely .if ever does bigger mean bigger rainforests, bigger wetlands and other habitats for nonhuman animal species, and bigger bio-regions that are not specifically human artifacts' (Bennett and Sylvan 1988, 156). Bigger consumption means bigger mess. Self-realization and voluntary simplicity may have been derived from Tao, but the issue of human overpopulation was not. Tao is silent on the issue. In the halcyon days of Tao, human overpopulation was not a problem. The then existing human population did not overfill and overrun its niche, nor overutilise its resource base. Now, from an ecological perspective, an expanding human population ranks among the greatest of environmental threats, for it is bound up with most major environmental problems (inter alia rates of consumption, inappropriate technologies, pollution, and extinction of species) but it is arelatively recent problem, i.e., with the last two hundred years. It is senseless to contemplate ecological sustainability without addressing human overpopulation. Human fertility can outstrip the possibility of ecological sustainability. The exponential growth of human population can outstrip the capacity of natural resources to sustain our species, let alone most others, whom humans would surely sacrifice before themselves. Population growth will generate increasing demands for goods like food .grains, fishery products, wood, minerals, and water. To make matters worse, these will generally be obtained in ways destructive and exploitative of the environment. To have ecological sustainability the earth must have an ecologically sustainable human population. Deep Ecologists consider two countermeasures to faunal and environmental destruction: reduction of the human population, and adoption and implementation of Deep Ecology's departure formulations, or some other set of principles that give rise to a heightened ecological consciousness. Besides attempting to preserve the environment, another course of action is to reduce the threat of devastation by reducing demands placed on the environment by a rapidly expanding human population. There is an inversely proportional relationship between these countermeasures. The larger the human population the more urgent it is to supersede environmentally insensitive policies with ecologically-inspired and sensitive policies. Conversely, the lower the human population 9 (then theoretically) the more likely that human devastation of the environment can be contained without the immediate adoption of deep ecological principles. Naess states, 'The flourishing of human life and cultures is compatible with a substantial decrease of the human population. The flourishing of non-human life requires such a decrease' (Naess 1984, 4). Among the most frequent misrepresentations of Deep Ecology or for that matter any call for a reduction of in the size of the human population are the charges of crude eco-brutalism or genocide. Deep Ecology's call for a reduction in the size of the human population is neither a call for eco-brutalism nor genocide. First, the loss of any species including humans is a tragedy devoutly to be avoided. If, for no other reason, a decrease in diversity is contrary to Deep Ecological principles. For Deep Ecology, there is a core democracy in the ecosphere. Massive reduction in human numbers would very likely enhance diversity in most habitats, because threatened species would have an opportunity to recover and because species with restricted distributions could spread out again. The nonhuman environment cannot sustain, nor be expected to continue to sustain, the increasing rates of population growth; and the problems cannot be resolved unless the rate of growth and the population growth cease altogether. Second, despite ludicrous misrepresentations of Deep Ecology by people like a San Francisco journalist, Christopher Reed, no violence is implied. Reed talks of the ecological movement containing 'hysterical extremism in a manner nastily reminiscent of Hitler's volk-ism', thus equating Deep EcolO¥Y to a kind of 'environmental Nazism' (R\!ed 1988, 3). The decrease in numbers should be through natural attrition and negative population growth among other things, but not violent methods. Although not stated as a principle, non-violence is an implicit norm common to most Deep Ecologists. It is violence against the environment which Deep Ecologists wish to change; they do not wish to perpetuate violence to do it. Maintaining the current growth economy mania is more likely to produce violence, ecobrutalism, and genocide. Population dynamics predict a decline in the human population will occur anyway. In other species overpopulation leads to population crashes where the population 'falls to around one-third the original level and it does it fast' (Taylor 1970, 227). First, a virorunental Ethics, paper commissioned by UNESCO on status of environmental philosophy in Australia' by Richard Sylvan and myself. I wish to acknowledge my indebtedness to Richard for his contributions to this paper. population explosion occurs when the methods of regulation break down or as in the case of human population are suspended through technology and social artifice. Then a decline or crash occurs when the population exceeds its resources or stress sets in. Although an artificially high human population (or the populations of other species, if humans so chose) can be supported by technology and redistribution of resources, the inevitable while postponed is nonetheless inevitable. Even the postponement of the inevitable by technology comes with the caveat that the more people the world carries the more care must be taken about what is done with technology and its by-products (see Flannery and Conlon 1989). Furthermore, it is interesting to note that while technology and redistribution may keep the wolf from the door (at least for the affluent who can afford doors), social and environmental stress will most likely set in first and there is little or nothing that technology can do about that. To return to Tao for a moment, although Tao is silent on the issue of population, it is not useless in addressing the population problem . The idea of harmony with nature in Tao implies that a human population level incompatible with or overly stressful on the capacity of nature to provide is contrary to the import of Tao. Recall the metaphor of the chef cutting with the grain of the meat and along the bone rather than across it. The chef is in harmony with her/his resources. While overpopulation was not an issue for Tao, disharmony was. Overpopulation is an example of disharmony par excellence. It cuts across the bones of ecological sustainability. The richness of the relationships between Tao and Deep Ecology is not exhausted by these areas of collaboration, but they do give the flavour of the relationships among Tao, deep environmental ethics and ecological sustainability. They go some way towards answering the initial questions of 'What are the relationships among ecological sustainability, deep environmental ethics and Tao? ' and 'What can Tao offer Western approaches to ecological sustainability?' Leopold, A. (1953) Round River: From the Journals of Aldo Leopold. London: Oxford University Press. Acknowledgement Leopold, A. (1966). A Sand County Almanac. New York: Oxford. (First published 1949). Significant portions of this paper use and are based on the papers 'Tao and Deep (Ecological) Theory' and 'Australian Perspectives on En- Naess, A. (n.d.) 'Individualism or Collectivism? ' Oslo: unpublished, 3pp. 10 Bibliography Austin, N. (1989) 'Our Dying Oceans- Can We Save Them?', Bulletin, 24 January: 36-42. Bennett, D.H. and R. Sylvan. (1988) 'Ecological Perspectives on an Expanding Human Population', in L.H. Day and D.T. Rowland, (eds) How Many More Australians? Melbourne: Longman Cheshire: 153-166. Chan, W.T. (1963) The Way of Lao Tzu (Tao-te Ching). New Yorlc: Bobbs Merrill. Commission For The Future. (1989) Personal Action Guide For The Earth. Canberra: AGPS. Devall, W. and G. Sessions. (1985) Deep Ecology: Living As If Nature Mattered. Salt Lake City: Gibbs M. Smith. Eckersley, R. (1988) 'The Need to Raise Our Eyes to the Horizon of Our Future', Canberra Times, 29 November: 9. Endangered Species Advisory Committee. (1989) An Australian National Strategy For The Conservation of Species and Habitats Threatened With Extinction. Canberra: Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service. Flannery, T. and T. Conlon. (1989) 'A Vaccine For The Plague?', Australian Natural History, 23: 148-155. I Hemenway, D. (1986) 'The Fate Of Our Forests: A Time To Choose.' In The International Permaculture Species Yearbook: 1986, D. Hemenway, ed. Orange, MA: TIPSY. Naess, A. (1984) ' What is Basic to Deep Ecology '. Canberra: unpublished. 5pp. Taylor, A-M. (1987) 'The Psychology of Activism ', in F. Fisher (ed) Sustaining Gaia: Contributions to Another World View. Clayton, Vic.: Monash University Graduate School of Environmental Science: 100-104. (Papers from : Environment, Ethics and Ecology II: 1984). Naess, A. and G. Sessions. (1984) 'Basic Principles of Deep Ecology', Ecophilosophy, VI, 37. Reed, C. (1988) 'The New Age of Nature's Warriors', Melbourne Age, 25 June: Saturday Extra 3. Taylor, G.T. (1970) The Doomsday Book. London: Thames and Hudson. Sylvan, R. (1985) 'A Critique of Deep Ecology'. Canberra: Australian National University, Departments of Philosophy. (Discussion Papers in Environmental Philosophy, 12). Williams, R. (1987) ' Conservation or Catastrophe'. Local Government Bulletin, 42: 14-17. World Commission On Environment And Development (1987) Our Common Future. London: Oxford University Press. 1 11 Appendix 1. Deep Ecology contrasted with the dominant paradigm and with Taoism Dominant (Western) paradigm Deep Ecology (DE) Domination over Nature Harmony Nature Elaboration of DE Nature a Resource Intrinsic Value confined to humans Natural Environment Valued for Itself Much as for DE; 'humanism' rejected Human supremacy Biocentric Egalitarianism Differs from DE; wide impartiality Ample Resources/ Substitutes Earth Supplies Limited Supplies ample Material Economic a predominant goal Non-material Goods, especially SelfRealization Following Growth Tao-Te Consumerism Doing with Enough/ Recycling Doing with Enough (recycling inappropriate) Competitive lifestyle Cooperative lifeway Much as DE; Voluntary Simplicity Centred/National focus Bioregional/ Neighbourhood focus Power structure Hierarchical Non-hierarchical/ Grassroots Democracy Hierarchy without Power Structure High Technology Appropriate Technoloogy Limited Technology 12 Taoism I