safety management systems for regular public transport operations

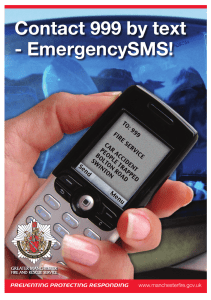

advertisement