Volume 27

Number 2

April 2014

Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings

Multipatient Studies

79 Validation of Rules of TwoTM as a paradigm for assessing asthma

control

83

M. Millard, M. Hart, and S. Barnes

Impact of a surveillance screening program on rates of methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus infections with a comparison of

surgical versus nonsurgical patients

125 Triple-hit lymphoma

Improving hospital staff compliance with environmental cleaning

behavior

L. Ramphal, S. Suzuki, I. M. McCracken, and A. Addai

92

Ethnic disparities in the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in

American adults: data from the Examination of National Health and

Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2010

L. Ramphal, J. Zhang, and S. Suzuki

96

A cohort analysis of the cardiovascular risk factors in the employees of

a pediatric hospital from 2009 to 2012

L. Ramphal, J. Zhang, and S. Suzuki

100

Volume 27, Number 2 • April 2014

Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, Texas

Factors affecting adherence to a quality improvement checklist on an

inpatient hepatology service

E. B. Tapper and M. Lai

103

Characteristics of Native Americans with HIV and implications for

care

C. Connel, J. S. Stroup, J. R. Stephens, and E. Martin

106

Comparison of the frequency and level of serum total cholesterol

>300 mg/dL in patients at the same Texas hospital in a single

month in 1993 and in 2013

W. C. Roberts, J. M. Ko, and R. Benavides Jr.

D. L. Glancy and D. L. Prout Jr.

N. Pemmaraju, J. Gill, S. Gupta, and J. R. Krause

128 Small bowel intussusception causing a postoperative bowel obstruction

following laparoscopic low anterior resection in an adult

A. S. Hussain, R. Warrier, and H. T. Papaconstantinou

131 Fatal abdominal hemorrhage associated with gallbladder perforation

due to large gallstones

L. R. Soto, H. R. Levine, S. A. Celinski, and J. M. Guileyardo

133 Methemoglobinemia precipitated by benzocaine used during

intubation

A. Afzal, R. Collazo, A. Z. Fenves, and J. Schwartz

136 Where is that hemodialysis catheter (superior vena cava or aorta)?

A case of intraarterial catheter placement

V. Tan and J. C. Schwartz

139 Renal failure due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus generalized

Shwartzman reaction from a dog bite (DF-2 nephropathy)

V. Tan and J. C. Schwartz

141 Imaging manifestations of a dreaded obstetric complication in the

immediate postpartum period

H. Levine, M. Zarghouni, and W. Cannon

143 Fetal demise due to cord entanglement in the early second trimester

R. N. Ergin, M. Yayla, and A. S. Ergin

145 Ingrown toenails (unguis incarnatus): nail braces/bracing treatment

Case Studies

108 Opsoclonus myoclonus syndrome: an unusual presentation for West

Nile virus encephalitis

A. Afzal, S. Ashraf, and S. Shamim

111

Fatal Clostridium septicum infection in a patient with a hematological

malignancy

R. Panikkath, V. Konala, D. Panikkath, E. Umyarova, and F. Hardwicke

113

Pages 77–196

Bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis associated with the use of the tumor

necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor adalimumab

M. M. Benjamin, A. W. Martin, and R. L. Rosenblatt

116

Celiac artery disease and fatal rupture of a hepatic artery aneurysm in

the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

A. Nat, T. George, G. Mak, A. Sharma, A. Nat, and R. Lebel

118

120

To access Baylor’s physicians, clinical services, or

educational programs, contact the Baylor Physician

ConsultLine: 1-800-9BAYLOR (1-800-922-9567)

D. L. Glancy and M. Singh

124 Inverted P waves, QRS complexes, and T waves in lead I in a 64-yearold woman

A. Jennings, M. Bennett, T. Fisher, and A. Cook

88

123 Irregular cardiac rhythm with wide QRS complexes

The most common cause of hemoptysis worldwide: a fluke?

Editorials, Tributes, Book Review

150 Tributes to George J. Race, MD, PhD

W. L. J. Edwards, J. W. Fay, M. Ramsay, A. D. Roberts Jr., and M. J. Stone

153 Cardiologist in the shadow of Angkor Wat: a medical mission to

Cambodia

J. D. Cantwell

156 A tale of Congress, continuing medical education, and the history of

medicine

C. Partin, H. I. Kushner, and M. E. Kollmer Horton

161 Mentoring: a tale of two poems, filling graveyards, and learning the art

of medicine

C. Partin

A. Nat, A. Nat, A. Sharma, G. Shastri, and M. C. Iannuzzi

163 HIPAA: a flawed piece of legislation

Stress-induced (takotsubo) cardiomyopathy following thoracic epidural

steroid injection for postherpetic neuralgia

166 Book review: Selected Roberts Papers from Seven Generations

N. P. McKernan, B. J. Rondeau, and R. K. McAllister

122

A. Chiriac, C. Solovan, and P. Brzezinski

Invited commentary: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy following epidural

steroid injection: yet another way to break the heart

A. B. Weisse

F. D. Winter Jr.

168 From the editor: Facts and ideas from anywhere

W. C. Roberts

J. M. Schussler

www.BaylorHealth.edu/Proceedings

Indexed in PubMed, with full text available through PubMed Central

Baylor University Medical Center

Proceedings

The peer-reviewed journal of Baylor Health Care System, Dallas, Texas

Volume 27, Number 2 • April 2014

Editor in Chief

William C. Roberts, MD

Associate Editor

Michael A. E. Ramsay, MD

Founding Editor

George J. Race, MD, PhD

Dennis R. Gable, MD

D. Luke Glancy, MD

L. Michael Goldstein, MD

Paul A. Grayburn, MD

Bradley R. Grimsley, MD

Joseph M. Guileyardo, MD

Carson Harrod, PhD

H. A. Tillmann Hein, MD

Daragh Heitzman, MD

Priscilla A. Hollander, MD, PhD

Ronald C. Jones, MD

Roger S. Khetan, MD

Göran B. Klintmalm, MD, PhD

Sally M. Knox, MD

John R. Krause, MD

Joseph A. Kuhn, MD

Zelig H. Lieberman, MD

Jay D. Mabrey, MD

Michael J. Mack, MD

Peter A. McCullough, MD, MPH

Gavin M. Melmed, JD, MBA, MD

Robert G. Mennel, MD

Dan M. Meyer, MD

Michael Opatowsky, MD

Joyce A. O’Shaughnessy, MD

Dighton C. Packard, MD

Gregory J. Pearl, MD

Robert P. Perrillo, MD

Daniel E. Polter, MD

Irving D. Prengler, MD

Chet R. Rees, MD

Randall L. Rosenblatt, MD

Lawrence R. Schiller, MD

W. Greg Schucany, MD

wc.roberts@BaylorHealth.edu

Editorial Board

Jenny Adams, PhD

W. Mark Armstrong, MD

Raul Benavides Jr., MD

Joanne L. Blum, MD, PhD

C. Richard Boland Jr., MD

Jennifer Clay Cather, MD

Evangeline T. Cayton, MD

James W. Choi, MD

Cristie Columbus, MD

Barry Cooper, MD

R. D. Dignan, MD

Gregory G. Dimijian, MD

Michael Emmett, MD

Andrew Z. Fenves, MD

Giovanni Filardo, PhD

Adrian E. Flatt, MD

James W. Fleshman, MD

Editorial Staff

Managing Editor

Cynthia D. Orticio, MA, ELS

Administrative Liaison

Dana M. Choate, MBA, RHIA, CHP

Jeffrey M. Schussler, MD

S. Michelle Shiller, DO

Michael J. Smerud, MD

Marvin J. Stone, MD

C. Allen Stringer Jr., MD

William L. Sutker, MD

Gary L. Tunell, MD

Beverlee Warren, MA, MS

Wilson Weatherford, MD

Lawrence S. Weprin, MD

F. David Winter Jr., MD

Larry M. Wolford, DMD

Scott W. Yates, MD, MBA, MS

Residents/Fellows

Mina Benjamin, MD

Kyle Gummelt, DO

Design and Production

Aptara, Inc.

Cynthia.Orticio@BaylorHealth.edu

Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings (ISSN 0899-8280), a peer-reviewed

journal, is published quarterly (January, April, July, and October). Proceedings is

indexed in PubMed and CINAHL; the full text of articles is available both at www.

BaylorHealth.edu/Proceedings and www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov. The journal’s mission is to communicate information about the research and clinical activities, continuing education, philosophy, and history of the Baylor Health Care System.

Funding for the journal is provided by the following:

• Baylor Health Care System Foundation

• Helen Buchanan and Stanley Joseph Seeger Endowment for Surgery

Funding is also provided by donations made by the medical staff and subscribers. These donations are acknowledged each year in the April or July issue. For

more information on supporting Proceedings and Baylor Health Care System

with charitable gifts and bequests, please call the Foundation at 214-820-3136.

Donations can also be made online at http://give.baylorhealth.com/.

Statements and opinions expressed in Proceedings are those of the authors and

not necessarily those of Baylor Health Care System or its board of trustees.

Guidelines for authors are available at http://www.baylorhealth.edu/Research/

Proceedings/SubmitaManuscript/Pages/default.aspx.

Subscriptions are offered free to libraries, physicians affiliated with Baylor, and

other interested physicians and health care professionals. To add or remove your

name from the mailing list, call 214-820-9996 or e-mail Cynthia.Orticio@

BaylorHealth.edu. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Baylor Scientific

Publications Office, 3500 Gaston Avenue, Dallas, Texas 75246.

Advertising is accepted. Acceptance of advertising does not imply endorsement

by Baylor University Medical Center. For information, contact Cindy Orticio

at Cynthia.Orticio@BaylorHealth.edu.

Permission is granted to students and teachers to copy material herein for

educational purposes. Authors also have permission to reproduce their own

articles. Written permission is required for other uses and can be obtained

through Copyright.com.

Copyright © 2014, Baylor University Medical Center. All rights reserved. Printed

in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Press date: March 7, 2014.

To access Baylor’s physicians, clinical services, or educational programs, contact

the Baylor Physician ConsultLine: 1-800-9BAYLOR (1-800-922-9567).

77

Clinical research studies enrolling patients through

Baylor Research Institute

Currently, Baylor Research Institute is conducting more than 800 research projects. Studies open to enrollment are listed in

the Table. To learn more about a study or to enroll patients, please call or e-mail the contact person listed.

Table. Clinical research studies conducted through Baylor Research Institute that are enrolling patients

Research area

Asthma and

pulmonary disease

Specific disease/condition

Contact information (name, phone number, and e-mail address)

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma (adult)

Rose Boehm, CCRC, RRT, RCP

Jana Holloway, RRT, CRC

214-820-9772

214-820-9772

RoseB@BaylorHealth.edu

janahol@baylorhealth.edu

Breast, ovarian, endometrial, prostate, brain, lung, bladder, colorectal, pancreatic,

and head and neck cancer; hematological malignancies, leukemia, multiple

Grace Townsend

myeloma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; melanoma vaccine; bone marrow transplant

214-818-8472

cancer.trials@BaylorHealth.edu

Treatment-naive colorectal cancer

Allison Cox

214-820-6779

marya.cox@baylorhealth.edu

Type 1 and type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular events

Kris Chionh

214-820-3416

kristen.chionh@BaylorHealth.edu

Pancreatic islet cell transplantation for type I diabetics, who either have or

have not had a kidney transplant

Kerri Purcell, RN

817-922-4640

kerrip@BaylorHealth.edu

Type 2; cardiac events

Trista Bachand, RN

817-922-2587

trista.bachand@baylorhealth.edu

Pancreatic islet cell transplantation for type I diabetics, who either have or

have not had a kidney transplant

Kerri Purcell, RN

817-922-4640

kerrip@BaylorHealth.edu

Crohn’s disease

Fabrienne English

214-818-9688

fabrienne.english@baylorhealth.edu

Healthy subjects needing colonoscopies

Allison Cox

214-820-6779

marya.cox@baylorhealth.edu

Heart and vascular

disease (Dallas)

Aortic aneurysms, coronary artery disease, hypertension, poor leg circulation,

heart attack, heart disease, congestive heart failure, angina, carotid artery

disease, familial hypercholesterolemia, renal denervation for hypertension,

diabetes in heart disease, cholesterol disorders, heart valves, thoracotomy pain,

stem cells, critical limb ischemia, cardiac surgery associated with kidney injury,

pulmonary hypertension

Merielle Boatman

214-820-2273

MeriellH@BaylorHealth.edu

Heart and vascular disease

(Fort Worth)

Atrial fibrillation, carotid artery stenting

Deborah Devlin

817-922-2575

Deborah.Devlin@BaylorHealth.edu

Heart and vascular disease

(Legacy Heart)

At risk for heart attack/stroke; previous heart attack/stroke/PAD; cholesterol

disorders; atrial fibrillation; overweight/obese; other heart-related conditions

Angela Germany

214-800-6469

lhcresearch@baylorhealth.edu

Heart and vascular

disease (Plano)

Aneurysms; coronary artery disease; surgical renal denervation, or stent,

for uncontrolled hypertension; poor leg circulation; heart attack; heart

disease; heart valve repair and replacement; critical limb ischemia; repair

Natalie Settele, PA-C

of AAA, TAA, and dissections with endografts; thoracic surgery leak

repair; atrial fibrillation; carotid artery disease; congestive heart failure;

left atrial appendage and stroke; gene profiling

469-814-4712

natalie.settele@BaylorHealth.edu

Hepatology

Liver disease

Jonnie Edwards

214-820-6243

jonnie.edwards@baylorhealth.edu

HIV/AIDS

Bryan King, LVN

214-823-2533

bryan.king@ntidc.org

Cancer

Diabetes (Dallas)

Diabetes (Fort Worth)

Gastroenterology

Infectious disease

Hepatitis C, hepatitis B

Jonnie Edwards

214-820-6243

Jonnie.edwards@baylorhealth.edu

Homocysteine and kidney disease, dialysis fistulas, urine/protein disorders

in cancer patients

Dallas Clinical Trials Office

214-818-9688

Fabrienne.english@baylorhealth.edu

Stroke

Dion Graybeal, MD

214-820-4561

Dion.Graybeal@BaylorHealth.edu

Multiple sclerosis

Annette Okai, MD

214-820-4655

annette.okai@BaylorHealth.edu

Neurosurgery

Cerebral aneurysms

Kennith Layton, MD

214-827-1600

KennithL@BaylorHealth.edu

Rheumatology (9900 N.

Central Expressway)

Rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, lupus, gout, ankylosing spondylitis

Krystine Cethoute

214-987-1249

krystine.cethoute@baylorhealth.edu

Bone marrow, blood stem cells

Grace Townsend

214-818-8472

Grace.Townsend@BaylorHealth.edu

Solid organs

Jonnie Edwards

214-820-6243

jonnie.edwards@baylorhealth.edu

Obesity

Kris Chionh

214-820-3416

kristen.chionh@BaylorHealth.edu

Endometriosis and endometrial ablation

Theresa Cheyne, RN

817-922-2579

theresa.cheyne@BaylorHealth.edu

Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome

Cathy Frisinger

817-922-2574

cathy.frisinger1@baylorhealth.edu

Nephrology

Neurology

Transplantation

Weight management

Women’s health (Fort Worth)

Baylor Research Institute is dedicated to providing the support and tools needed for successful clinical research. To learn more

about Baylor Research Institute, please contact Kristine Hughes at 214-820-7556 or Kristine.Hughes@BaylorHealth.edu.

78

Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2014;27(2):78

Validation of Rules of TwoTM as a paradigm for assessing

asthma control

Mark Millard, MD, Mary Hart, MS, RRT, AE-C, and Sunni Barnes, PhD

Assessing asthma control at each patient encounter is an essential

task to determine pharmacologic requirements. Rules of Two (Ro2) was

created from the original 1991 National Asthma Education Program

guidelines to determine the need for controller therapy. This study determined the degree of agreement between Ro2 and the Expert Panel

Report (EPR-3) definition of “in control” asthma and compared that

value with the Asthma Control Test (ACT) in a group of asthmatics for

the purpose of validating this tool. Patients with documented asthma

were randomized to complete Ro2 or ACT prior to being assessed for

asthma control by certified asthma educators using an EPR-3 template.

Assessments occurred in either a specialty asthma clinic or at a local

health fair. Patients were also queried for their personal assessment

of asthma control. The primary statistical methodology employed was

the degree of agreement (kappa) between each survey tool and the

EPR-3 template. Of 150 patients, 72% did not have their asthma in

control, based on the EPR-3 template. Ro2 identified 58% of patients

not in control of their asthma, whereas ACT identified 36%, with kappa

scores of 0.41 for Ro2 and 0.37 for ACT compared with the EPR-3

template. These were not significantly different. Of the 150 patients,

75% considered their asthma in control based on self-assessments,

with a kappa of 0.23. In 14 of 73 ACT questionnaires, scores were not

added or were misadded. Eliminating evaluation of static lung function

significantly improved both kappa scores of Ro2 and ACT. In conclusion, Ro2 identifies patients with uncontrolled asthma as well as ACT

and may be useful to the primary assessing clinician in determining

asthma control.

he assessment of asthma control drives therapeutic decisions in patients with asthma, as articulated in the

2007 edition of the National Asthma Education and

Prevention Program (NAEPP) (1), also referred to as

the Expert Panel Report (EPR-3). That assessment reflects the

contributions of two related domains, impairment and risk, and

consists of patient-reported symptoms and symptom frequency,

documentation of health care encounters, medication use, and

objective measurement of lung function. The decision to step

up, step down, or maintain any specific therapy rests upon the

determination of asthma control.

Rules of TwoTM (Ro2) was created in 1992 as a tool to signal

the need for controller therapy according to the first National

T

Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2014;27(2):79–82

Asthma Education Program (NAEP) guidelines published in

1991. At that time, the use of controller therapy for patients

with persistent asthma had not been generally accepted within

the primary care community, and there was a need to develop

an easily remembered synopsis of the NAEP criteria for mild

persistent asthma, which was the point at which antiinflammatory therapy for asthma was first recommended. While abstracts demonstrating the impact of Ro2 educational efforts were

presented at annual American Thoracic Society conferences in

1999 (2) and 2000 (3), no specific validation of Ro2 was ever

attempted, primarily because the syntax of Ro2 was taken directly from NAEP and no specific need for separate validation

was perceived.

By contrast, the well-validated Asthma Control TestTM

(ACT) (4) introduced in 2004 followed a methodical development beginning with focus groups of asthma experts to identify

specific issues relevant to the assessment of asthma control and

then proceeding to demonstrate the most robust of these items,

ultimately resulting in a validation for both adult and pediatric

communities of the ACT as a standardized patient-reported

questionnaire to assess asthma control. Multiple studies have

since demonstrated ACT’s relevance in predicting asthma morbidity (5, 6), and the 2007 NAEPP guidelines identified ACT

as one of three validated patient-reported evaluations that could

be used to assess asthma control.

The 2007 EPR-3 published a table enumerating multiple

determinants of asthma control using the two domains of impairment and risk (Table 1) (1). Using this table as a template

for good control, the current study compared the agreement

between this standard and either the Ro2 (Figure 1) or the ACT

(Figure 2) in predicting asthma control in a cohort of patients

with documented asthma.

METHODS

This study recruited subjects with healthcare professional–

diagnosed asthma who were taking prescription asthma

From the Baylor Martha Foster Lung Care Center, Baylor University Medical

Center at Dallas (Millard, Hart), and the STEEEP Global Institute, Dallas, Texas

(Barnes).

Corresponding author: Mark Millard, MD, Baylor Foster Lung Care Center, 4004

Worth Street, Dallas, TX 75246 (e-mail: markmi@baylorhealth.edu).

79

Table 1. Assessing asthma control and adjusting therapy in youths ≥12 years of age and adults*

Classification of asthma control (≥12 years of age)

Components of control

Well controlled

Not well controlled

>2 days/week or multiple times

on ≤2 days/week

Throughout the day

Nighttime awakenings

≤1x/month

≥2x/month

≥2x/week

Interference with normal activity

None

Some limitation

Extremely limited

>2 days/week

Several times per day

>80% predicted/personal best

>80%

60−80% predicted/personal best

75−80%

<60% predicted/personal best

<75%

Exacerbations requiring oral systemic

corticosteroids

0−1/year

≥2/year (see note)

Reduction in lung growth

Evaluation requires long-term followup.

Treatment-related adverse effects

Medication side effects can vary in intensity from none to very troublesome and worrisome. The level of

intensity does not correlate to specific levels of control but should be considered in the overall assessment of risk.

Short-acting beta2-agonist use for

≤2 days/week

symptom control (not prevention of EIB)

Lung function

• FEV1 or peak flow

• FEV1/FVC

Risk

Very poorly controlled

≤2 days/week but not more

than once on each day

Impairment Symptoms

Consider severity and interval since last exacerbation

*Reprinted from Expert Panel Report 3 (1).

EIB indicates exercise-induced bronchospasm; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Notes:

• The level of control is based on the most severe impairment or risk category. Assess impairment domain by patient’s/caregiver’s recall of previous 2–4 weeks and by

spirometry or peak flow measures. Symptom assessment for longer periods should reflect a global assessment, such as inquiring whether the patient’s asthma is better or

worse since the last visit.

• At present, there are inadequate data to correspond frequencies of exacerbations with different levels of asthma control. In general, more frequent and intense exacerbations

(e.g., requiring urgent, unscheduled care, hospitalization, or intensive care unit admission) indicate poorer disease control. For treatment purposes, patients who had ≥2

exacerbations requiring oral systemic corticosteroids in the past year may be considered the same as patients who have not-well-controlled asthma, even in the absence of

impairment levels consistent with not-well-controlled asthma.

medications, excluding those with known chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary fibrosis, or other complicating lung disease. Patients with diagnosed asthma were

randomized in a 1:1 fashion to complete either Ro2 or ACT.

These self-reported tests were completed before assessment by

certified asthma educators, who used a template taken directly

from the EPR-3 guidelines to determine asthma control and

had no prior knowledge of patient responses to either Ro2 or

ACT. Not-well-controlled asthma was defined by the Ro2 as

any positive response to the four-item questionnaire and by

the ACT as a score of ≤19. The degree of agreement (kappa)

between the more comprehensive EPR-3 template and Ro2

or ACT, in addition to patient self-perception of control, was

calculated (7). A power analysis determined that a sample

size of 150 was needed to detect a true kappa value of 0.70

based on a significance level of 0.05. This study was approved

by the Baylor Health Care System institutional review board

(IRB #009-084).

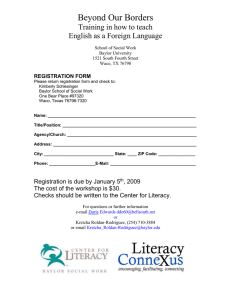

Please check the proper box. Thank you.

Do you have asthma symptoms or use your quick relief inhaler more

than two times per week?

Yes ___ No ___

Do you awaken at night with asthma symptoms more than two

times per month?

Yes ___ No ___

Do you refill a canister of quick relief medication more than two

times per year?

Yes ___ No ___

When you have asthma symptoms, does your peak flow

vary more than two times 10 (20%) from baseline?

Y e s __ _ N o _ __ I d o n ’ t k no w_ _ _

Figure 1. Rules of Two patient asthma questionnaire.

80

Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings

RESULTS

Of the 150 patients who participated in this study, 130 were

surveyed at the Baylor Martha

Foster Lung Care Center, an outpatient facility that is a part of Baylor

University Medical Center at Dallas, Texas, and provides specialized

asthma care. The remaining 20

patients were assessed at a local

women’s health fair. Spirometry

was performed on each patient.

The age of patients assessed ranged

from 14 to 86, with a median age

Volume 27, Number 2

individuals were judged “in control” by ACT but “not in control”

by EPR-3 (false-negative), yielding

Score

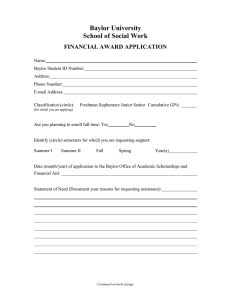

In the past 4 weeks, how much of the time did your asthma keep you from

1.

an overall agreement rate of 64%.

getting as much done at work, school or at home?

In comparison, the false-positive

1. All of the time 2. Most of the time 3. Some of the time

rate for “not in control” asthma for

4. A little of the time 5. None of the time

the Ro2 instrument was 5 out of

During the past 4 weeks, how often have you had shortness of breath?

2.

77 patients, and the false-negative

rate was 16 out of 77 patients. The

1. More than once a day 2. Once a day 3. 3 to 6 times a week

4. Once or twice a week 5. Not at all

overall agreement between Ro2 and

EPR-3 was 73%.

During the past 4 weeks, how often did your asthma symptoms (wheezing,

3.

coughing, shortness of breath, chest tightness or pain) wake you up at night or

Disagreements in the determiearlier than usual in the morning?

nation of asthma control by Ro2

1. 4 or more nights a week 2. 2 or 3 nights a week 3. Once a week

and ACT when compared with the

4. Once or twice 5. Not at all

EPR-3 template occurred primarDuring the past 4 weeks, how often have you used your rescue inhaler or

4.

ily in patients with lung function

nebulizer medication (such as albuterol)?

(forced expiratory volume in 1 sec1. 3 or more times per day 2. 1 or 2 times per day 3. 2 or 3 times per week

ond [FEV1] or FEV1/forced vital

4. Once a week or less 5. Not at all

capacity [FVC]) that was abnorHow would you rate your asthma control during the past 4 weeks?

5.

mal. Ten of the 16 patients judged

“in control” by Ro2 but not EPR-3

1. Not controlled at all 2. Poorly controlled 3. Somewhat controlled

4. Well controlled 5. Completely controlled

had abnormal lung function. Seventeen of 26 patients erroneously

Total

considered “in control” by ACT

likewise had abnormal pulmonary

Figure 2. Asthma Control Test.

function tests, although 7 of those

of 42 years; 33% were male and 67% female, which reflects the

17 patients had other positive responses to EPR-3 questions

increased adult female incidence of asthma in addition to incluthat would have resulted in a “not in control” determination,

sion of participants in the women’s health fair. In addition, 74%

despite an ACT score of >20. If resting lung function was not

were Caucasian, 17% African American, and 9% Hispanic.

used to determine asthma control in the EPR-3 tool, then the

As shown in Table 2, 109 of the entire group of 150 patients

kappa for both Ro2 and ACT would have been much higher

(72%) assessed using a template taken directly from EPR-3 were

(0.63 and 0.49, respectively). While not the primary endpoint

identified as having uncontrolled asthma, compared with 45 of

of this study, 14 of 73 ACT questionnaires failed to add up or

77 patients (58%) assessed with the Ro2 and 26 of 73 patients

misadded scores. For determination of kappa, additions were

(36%) assessed with the ACT. The degree of agreement, as ascompleted or corrected prior to analysis.

sessed using a kappa statistic, was 0.41 for Ro2 and EPR-3 and

0.37 for ACT and EPR-3. There was no statistical difference in

DISCUSSION

the agreement with EPR-3 between the Ro2 and ACT tools.

The fundamental concept of asthma “control” has been a

By contrast but as expected, agreement with patient perception

consistent element in the series of reports issued by the NAEP(P),

of self-control when compared to the EPR-3 assessment was

first in 1991, revised in 1997, and most recently in 2007 with

poor, with only 25% of patients feeling their asthma was “not

EPR-3. Delineation of impairment and risk domains is articuin control” (kappa 0.23).

lated in EPR-3, but the need for a comprehensive evaluation of

There were no false-positive ACT questionnaires when

specific aspects of asthma symptomatology and physiology is

compared to the EPR-3 template. However, 26 out of 73

longstanding and has been widely accepted as the standard for

asthma assessment. In this study, we used

the specific elements of control articulatTable 2. Determinations of in-control asthma based on different tests

ed in EPR-3 as the basis of comparison

for both Ro2 and ACT and overall deterAsthma in Asthma not in Agreement with

Agreement

mined “fair” agreement (8).

Test

control (%)

control (%)

EPR-3 (kappa) with EPR-3 (%)

A consistent finding of multiple paEPR-3 (n = 150)

28

72

–

–

tient

surveys is the discordance between

Ro2 (n = 77)

42

58

0.41

73

self-assessment of asthma control and the

ACT (n = 73)

64

36

0.37

64

assessment derived from asthma-specific

Patient self-assessment (n = 151)

75

25

0.23

37

questionnaires. The Asthma in America

EPR-3 indicates Expert Panel Report-3; Ro2, Rules of Two; ACT, Asthma Control Test.

Survey (1998) (9) quantified the discrepancy between patient perception of asthma

Please complete the following form about your asthma and add up your scores.

April 2014

Validation of Rules of TwoTM as a paradigm for assessing asthma control

81

control and reality from in-depth questionnaires. Our group demonstrated that discordance in a group of self-identified asthmatics

attending a state fair in the late 1990s (3). Subsequent follow-up

surveys have continued to demonstrate this disconnect (10). In

this study, as noted with earlier ones, a much higher percentage

of patients felt they were “in control” by self-assessment than were

considered by using an 8-question template drawn from EPR-3.

The baseline finding that over three fourths of patients assessed

with the EPR-3 tool were considered not in good control of their

asthma is consistent with other studies (9, 11) and not a unique

finding in our surveyed population. Both ACT and Ro2 identified patients who were “not in control,” but at a lower frequency

than the standard from EPR-3. Even so, Ro2 appeared to be a

slightly better tool than ACT for identifying patients who were

judged as “not in control.”

A number of other asthma self-report questionnaires exist,

such as the Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire (12)

and Asthma Control Questionnaire (13), which have likewise

been validated and are used for clinical research purposes and

are mentioned in EPR-3. We chose to compare the kappa of

R02 and ACT with a template taken directly from EPR-3, to

determine the degree to which both correlate with a more robust

set of determinants of control.

The most significant explanation for the reduced kappa

scores of both Ro2 and ACT with the EPR-3 comparator in

our studied population relates to the objective measurements of

static lung function, which classified more patients with asthma

as not well controlled by EPR-3 criteria. EPR-3 assumes an

abnormal FEV1 or FEV1/FVC to be reflective of uncontrolled

asthma (1). Our clinic population that attends a specialty asthma management center may include a more severe asthmatic

population, more likely to have chronically reduced lung function, an observation that might explain the lower kappa for

both assessment tools. A certain proportion of this population

may indeed manifest airway remodeling, which is unresponsive

to even more aggressive asthma therapy, according to EPR-3,

despite minimal symptomatology (1). At least one author has

written that using lung function as a marker of uncontrolled

asthma is misleading (14). In our studied population, the kappa

scores for Ro2 and ACT improve quite significantly if lung

function measurements are not considered part of the equation

of good asthma control; in fact, excluding static lung function

scores improves agreement to “substantial” in the case of R02

and “moderate” with ACT (8).

In this study, Ro2 was more likely to be completed than

ACT. Indeed, an advantage of Ro2 over ACT lies in the fact

that no computation is needed to come up with a score, which

makes it easier for patients to complete and for clinicians to

interpret. The specific contents of Ro2 help frame the conversation between clinician and patient about asthma, move beyond

reported self-perceptions of asthma control, and allow for a brief

but potent clinical encounter to determine asthma control and

the potential need for changes in therapy.

In conclusion, the current study shows that both Ro2 and

ACT identified patients with out-of-control asthma with similar agreement when compared to an EPR-3 assessment (Ro2

82

kappa = 0.41; ACT kappa = 0.37). Ro2 had a higher rate of

agreement with EPR-3 in the classification of patients in control

vs. out of control when compared with ACT (73% vs. 64%).

Removing the measurement of static lung function significantly

improves both kappa scores. While both Ro2 and ACT share

statistically similar agreement with an EPR-3 template for good

asthma control, Ro2 is more likely to be completed by patients

and shows a slightly higher level of agreement with the standard

EPR-3 assessment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Baylor Martha Foster

Lung Center team of certified asthma educators who assessed each

patient: Erika Abmas, RRT, AE-C, Rose Boehm, RRT, AE-C,

Laura Blundell, BS, RRT, AE-C, Lynn Burleson, RRT, AE-C, and

Grace Hernandez, BS, RRT, AE-C. Grateful thanks are also given

to Cynthia Orticio for her help in preparing this document for

publication. Funding was provided by Baylor University Medical

Center at Dallas and Baylor Research Institute. Rules of TwoTM

is a registered trademark of Baylor Health Care System. ACTTM

is a registered trademark of QualityMetrics Inc.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report

3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Bethesda, MD:

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, 2007. Available at http://www.

nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/.

Millard M. The Dallas Asthma Consortium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

1999;159:A126.

Millard M. Health fair awareness initiatives: an outcomes report. Am J

Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:A405.

Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, Schatz M, Li JT, Marcus P, Murray

JJ, Pendergraft TB. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for

assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004;113(1):59–65.

Shirai T, Furuhashi K, Suda T, Chida K. Relationship of the asthma control test with pulmonary function and exhaled nitric oxide. Ann Allergy

Asthma Immunol 2008;101(6):608–613.

Schatz M, Sorkness CA, Li JT, Marcus P, Murray JJ, Nathan RA, Kosinski

M, Pendergraft TB, Jhingran P. Asthma Control Test: reliability, validity,

and responsiveness in patients not previously followed by asthma specialists. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;117(3):549–556.

Altman DG. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. London: Chapman

& Hall, 1991: 404.

Viera A, Garrett J. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa

statistic. Fam Med 2005;37(5):360-363.

GlaxoSmithKline. The state of asthma in America: two landmark surveys.

As discussed in http://www.mainehealth.org/workfiles/mh_professional/

Asthma/ACTJournal.pdf.

Shering-Plough. Asthma Insight and Management (AIM) national survey:

Executive summary. Available at CHEST 2010.

Nathan RA, Meltzer EO, Blais MS, Murphy KR, Doherty DE, Stoloff

SW. Comparison of the Asthma in America and Asthma Insight and

Management surveys: Did asthma burden and care improve in the United

States between 1998 and 2009? Allergy Asthma Proc 2012;33(1):65–76.

Vollmer WM, Markson LE, O’Connor E, Sanocki LL, Fitterman L, Berger

M, Buist AS. Association of asthma control with health care utilization

and quality of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160(5 Pt 1):1647–

1652.

Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Epstein RS, Ferrie PJ, Jaeschke R, Hiller TK. Evaluation of impairment of health related quality of life in asthma: development

of a questionnaire for use in clinical trials. Thorax 1992;47(2):76–83.

Stempel DA, Fuhlbrigge AL. Defining the responder in asthma therapy.

J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;115(3):466–469.

Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings

Volume 27, Number 2

Impact of a surveillance screening program on rates of

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections with a

comparison of surgical versus nonsurgical patients

Andrew Jennings, MD, Monica Bennett, PhD, Tammy Fisher, RN, BBA, and Alan Cook, MD

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a significant cause of

health care–associated infection. The overall effectiveness of surveillance

screening programs is not well established. A retrospective cohort study

was performed to evaluate the impact of a surveillance screening program

on the rates of health care–associated MRSA infection (HA-MRSA-I) at a

single institution. A subset of surgical patients was analyzed separately.

Multivariate regression techniques were used to identify predictors of the

desired outcomes. The overall MRSA infection rate was 1.3% in the before

cohort and 3.2% in the after cohort. After excluding patients with a history of MRSA infection or MRSA colonization, HA-MRSA-I decreased from

1.2% to 0.87%. There was a similar overall increase in the surgical group,

1.4% to 2.3%, and decrease in HA-MRSA-I, 1.4% to 1.0% (P < 0.001).

For all patients, surgery, African American race, and increased length of

stay conferred an increased likelihood of HA-MRSA-I. Females and patients

in the after cohort had a lower risk of HA-MRSA-I (P < 0.01). In the after

cohort, the results were similar, with surgery, African American race, and

length of stay associated with an increased risk, and female sex associated

with a decreased risk (P < 0.05). African American race and increased

age had a higher likelihood of screening positive for MRSA colonization,

while the surgical group, females, and Hispanic patients were less likely

(P < 0.05). HA-MRSA-I was associated with a higher mortality among all

patients (P < 0.001). Mortality rates were similar with HA-MRSA-I for all

patients (10.8% vs 9.5%, P = 0.55) and in the surgical group (8.3% vs

6.8%, P = 0.58). In conclusion, surveillance programs may be effective

in decreasing HA-MRSA-I. Further studies are needed to determine how

to reduce transmission, particularly among African Americans and those

with increased lengths of stay.

ethicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a

significant cause of health care–associated infection (1)

and is associated with increased hospital mortality (2,

3). In addition, MRSA is the leading cause of surgical

site infection (4, 5). In 2003, the Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America released guidelines strongly supporting the

use of active surveillance cultures and contact isolation programs

(6). A decrease in overall health care–associated MRSA infections

(HA-MRSA-I) has since been demonstrated across a wide range

of clinical and geographical settings in the United States (7).

Surveillance programs have also proven to be effective in MRSA

outbreaks in the intensive care unit (ICU) setting (8). Despite a

M

Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2014;27(2):83–87

decrease in overall HA-MRSA-I rates after implementation of

active surveillance culture programs, the effect of HA-MRSA-I

rates on specific patient populations, including patients undergoing

invasive surgical procedures, is not well established (9, 10).

The purpose of this study was to evaluate rates of HA-MRSAI before and after implementation of a hospitalwide screening

program at a large teaching hospital with a high surgical volume.

We examined the effect of this infection control initiative in the

overall hospital population as well as for patients undergoing a

wide range of common surgical procedures among a variety of

specialties. We hypothesized that rates of HA-MRSA-I would

decrease after implementation of a screening program, both

hospitalwide and for patients undergoing surgical procedures.

METHODS

This institutional review board–approved retrospective cohort

study took place at Baylor University Medical Center at Dallas, a

1000-bed academic medical center and level I trauma center in a

large metropolitan area. Our current practice involves performing

nasal swab MRSA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) screens on all

patients who meet one of the following screening criteria: a prior

history of MRSA colonization or infection (patient is placed in contact isolation); hospitalization within the preceding year; transfer

from an extended care facility; presence of open or draining skin

wounds (patient is placed in contact isolation); current admission

to ICU; or current hemodialysis. Standard barrier and isolation

precautions, including gown and gloves, are applied to all patients

with a positive screen. With the exception of several four-bed pods

in the surgical intensive care unit, all rooms are single rooms.

A hospitalwide MRSA surveillance program was implemented in January 2009. Prior to this initiative, standard barrier

and isolation practices were implemented only if patients had a

documented MRSA infection or if the patient or patient’s history

indicated prior MRSA infection. For purposes of this study, the

term “MRSA infection” is used if a positive MRSA culture was

From the Department of Surgery, Baylor University Medical Center at Dallas.

Dr. Jennings is now with the Department of Surgery at The University of Texas

Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas.

Corresponding author: Andrew Jennings, MD, Department of Surgery, The

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard,

Dallas, TX 75390-9158 (e-mail: andrewjenningsmd@gmail.com).

83

obtained on a patient from any source. The term “positive screen”

is used for patients who had a positive nasal PCR screen denoting

MRSA colonization, but not an active MRSA infection.

All inpatient hospital admissions from October 1st to

September 30th for 2007 to 2008 (before cohort) and 2010

to 2011 (after cohort) were analyzed. The 12-month interval

between cohorts was included to allow full implementation

across all units of the hospital. All patients in the after cohort underwent nasal MRSA PCR screening under the criteria

mentioned above. Patients with a previous MRSA infection,

as well as those readmitted with a previous positive screen for

MRSA, were excluded. Patients who initially screened negative

and subsequently developed an MRSA infection were considered to have HA-MRSA-I. A subset of patients undergoing a

wide array of surgical procedures across multiple specialties in

the before and after cohort were analyzed separately. These included general surgical, gynecologic, orthopedic, cardiothoracic,

transplant, oral-maxillofacial, plastics, and urologic procedures.

International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification,

ninth revision (ICD-9) procedure codes were used to identify

procedures by those specialties. Procedures were included in

the analysis if at least 50 were performed during the study period. Logistic regression analysis was performed to determine

which factors contributed to predicting HA-MRSA-I and how

HA-MRSA-I affected patient mortality. P values <0.05 were

considered significant.

Our primary endpoint was the incidence of HA-MRSA-I.

The secondary endpoint was the impact of HA-MRSA-I on

patient mortality. Multivariate regression techniques were used

to elucidate predictors of these outcomes.

RESULTS

There were 36,244 patients in the before cohort, of whom

16,740 underwent a surgical procedure, and 36,068 in the

after cohort, of whom 15,044 underwent a

surgical procedure. Patient characteristics are

Table 1. Patient characteristics for all patients and patients in the surgical group

shown in Tables 1 and 2.

The overall MRSA infection rate was

Combined

Before

After

1.3% (453 patients) in the before cohort and

All patients

3.2% (1136 patients) in the after cohort (P <

N

72,312

36,244

36,068

0.001). When patients with previous MRSA

infection or colonization were excluded, those

Age at admit, mean ± SD (years)

54.2 ± 19.2

54.1 ± 19.1

54.2 ± 19.3

with HA-MRSA-I decreased from 1.2% to

Male

29,465 (41%)

15,020 (41%)

14,445 (40%)

0.87% (Table 3). Similarly, there was an inFemale

42,837 (59%)

21,216 (59%)

21,621 (60%)

crease in the rate of overall MRSA infection

Race

in the surgical group, from 1.4% to 2.3%,

White

43,215 (60%)

22,609 (63%)

20,606 (57%)

along with a decrease in HA-MRSA-I, from

African American

18,473 (26%)

8,712 (24%)

9,761 (27%)

1.4% to 1.0% (Table 3).

Hispanic

8,324 (12%)

3,770 (10.5)

4,554 (12.7%)

For the total patient population, including both before and after cohorts, patients in

Asian

705 (1%)

289 (0.8%)

416 (1.2%)

the surgical group, African Americans, and

Other

1047 (1.5%)

431 (1.2%)

616 (1.7%)

patients with an increased length of stay had

Length of stay, median (IQR) (days)

3.8 (2.3, 6.8)

3.8 (2.2, 6.8)

3.8 (2.3, 6.9)

an increased likelihood of developing HADischarged alive

69.761 (97%)

34,917 (96%)

34,844 (97%)

MRSA-I. Female patients and patients in the

Died

2,551 (4%)

1,327 (4%)

1,224 (3%)

after cohort were less likely to develop HASurgical group

MRSA-I (Table 4). When only patients in the

after

cohort were analyzed, the results were

N

31,784

16,740

15,044

similar, with surgery, African American race,

Age at admit, mean ± SD (years)

50.7 ± 18.5

51.1 ± 18.2

50.3 ± 18.8

and length of stay associated with an increased

Male

11,667 (37%)

6,416 (38%)

5,251 (35%)

risk of HA-MRSA-I, and female sex associFemale

20,109 (63%)

10,317 (62%)

9,792 (65%)

ated with a decreased risk (Table 4).

Race

With regards to the likelihood of screenWhite

21,021 (67%)

11,460 (70%)

9,561 (64%)

ing positive for MRSA colonization, African

American race and increased age were assoAfrican American

5,820 (19%)

2,901 (18%)

2,919 (20%)

ciated with a higher likelihood of screening

Hispanic

3,705 (12%)

1,727 (11%)

1,978 (13%)

positive, while patients in the surgical group,

Asian

373 (1.2%)

151 (1%)

222 (1.5%)

female patients, and Hispanic patients were

Other

473 (1.5%)

183 (1.1%)

290 (2%)

less likely to screen positive (Table 5). HALength of stay, median (IQR) (days)

3.6 (2.3, 6.8)

3.7 (2.3, 6.7)

3.5 (2.3, 6.9)

MRSA-I was associated with a higher morDischarged alive

31,239 (98%)

16,430 (98%)

14,809 (98%)

tality for both the entire patient population

Died

545 (1.7%)

310 (2%)

235 (2%)

and surgical group in both cohorts (Table 5).

There was no significant difference in the overSD indicates standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

all mortality of patients with HA-MRSA-I

84

Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings

Volume 27, Number 2

by 27.5% for the overall patient population

and 28.6% for the patients in the surgery

group. Patients with MRSA nasal colonizaVariable

Surgical (N = 31,784) Nonsurgical (N = 40,528) P value

tion are at a significant increased risk for the

Age at admit, mean ± SD (years)

50.7 ± 18.5

56.9 ± 19.3

<.0001

development of MRSA infections. Stenehjem

Male

11,667 (37%)

17,798 (44%)

and colleagues demonstrated this regardless

Female

20,109 (63%)

22,728 (56%)

<.0001

of the quantitative burden detected on PCR

screening. During their study period, 4.3%

Race

of noncarriers developed a MRSA infection

White

21,021 (67%)

22,194 (55%)

compared with 18.5% and 17.2% of low- and

African American

5,820 (19%)

12,653 (31%)

high-burden patients, respectively (12).

Hispanic

3,705 (12%)

4,619 (11%)

Previous studies have demonstrated a

Asian

373 (1.2%)

332 (0.8%)

greater than twofold increased incidence of

Other

473 (1.5%)

574 (1.4%)

<.0001

MRSA infections among African Americans,

66.5 per 100,000, versus the standardized

Length of stay, median (IQR) (days)

3.6 (2.3, 6.8)

3.9 (2.2, 6.8)

<.0001

incidence rate of 31.8 per 100,000. Male

Discharged alive

31,239 (98%)

38,522 (95%)

patients had slightly higher infection rates

Died

545 (1.7%)

2006 (5%)

<.0001

at 37.5 per 100,000, while patients older

SD indicates standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

than 65 years of age had rates of 127.7 per

100,000 (13). Our study showed that African American patients and patients with

for all patients (10.8% vs 9.5%, P = 0.55) as well as the surgical

increased lengths of stay were at increased risk of developing

group (8.3% vs 6.8%, P = 0.58).

MRSA infection, and that female patients had a decreased

risk. Graffunder and colleagues identified previous surgery

DISCUSSION

and longer lengths of stay before infection as independent risk

Our data indicate that the overall MRSA infection rate infactors for developing MRSA infection, along with previous

creased during the study period for the entire patient population

hospitalization, enteral feedings, and macrolide and levofloxaas well as for patients in the surgical group. This occurred despite

cin use (14).

implementation of the screening program. This is consistent

The major limitation of this study is its retrospective design.

with an overall increase in community-acquired MRSA infecTherefore, the majority of patients with a positive screen will

tions, which Mera and colleagues demonstrated as an increase

be in the after cohort when the policy became hospitalwide.

from 22.3% in 1998 to 66.1% in 2007 (11). The purpose of

Since these patients are known to be at increased risk of develthe MRSA screening program is to protect patients without

oping MRSA infection and were omitted from the final analyprevious colonization from acquiring an MRSA infection while

sis by our study criteria, this could potentially create a falsely

in the hospital (HA-MRSA-I). While the desired outcome is to

elevated rate of HA-MRSA-I in the before group. However,

decrease MRSA infection rates hospitalwide, surveillance progiven the retrospective observational nature of the study, the

grams can also have a positive impact on HA-MRSA-I, despite

data pertaining to the rate of nasal carriage in the before group

an overall increase in MRSA infection rate.

were not available. Nonetheless, the method of documenting

When excluding patients with a history of MRSA infection

HA-MRSA-I is consistent between the groups. Furthermore,

or MRSA colonization, the overall HA-MRSA-I rate decreased

no data regarding compliance with the screening protocol were

available for our analysis. Suboptimal compliance with hand hygiene (52%, range 27%–

86%), glove use (62%, range 11%–98%), and

Table 3. MRSA infection rates for patients in both cohorts

the use of gown or other protective clothing

Cohort

Infection

Time

Yes

No

P value

(57%, range 8%–93%) was reported by

All

All positive cultures

Before

453 (1.3%)

35,791 (98.8%)

Gammon et al (15).

Improved MRSA infection rates have

After

1136 (3.2%)

34,932 (96.9%)

<.001

been

demonstrated in certain patient popuOnly HA-MRSA-I

Before

426 (1.2%)

35,791 (98.8%)

lations where more aggressive measures were

After

307 (0.87%)

34,932 (99.1%)

<.001

taken than standard barrier and isolation

Surgical

All positive cultures

Before

236 (1.4%)

16,504 (98.6%)

practices. MRSA infection rates decreased

After

345 (2.3%)

14,699 (97.7%)

<.001

by 93% in cardiac surgical wounds after a

Only HA-MRSA-I

Before

229 (1.4%)

16,504 (98.6%)

program was initiated that not only screened

patients, but included additional intervenAfter

148 (1.0%)

14,699 (99.0%)

0.002

tions such as decolonizing hospital staff

HA-MRSA-I indicates health care–associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection.

who screen positive, providing vancomycin

Table 2. Comparison of surgical versus nonsurgical patients

April 2014

Impact of a surveillance screening program on rates of MRSA

85

Table 4. Factors associated with health care–associated methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus infection

Category

Variable

Odds ratio

95% CI

P value

(0.63, 0.85)

<.001

In all patients

Cohort

Before

After

Surgery

0.73

No (referent)

—

Yes

1.3

(1.12, 1.51)

<.001

1

(1.00, 1.01)

0.07

Male (referent)

—

Age

Sex

—

HA-MRSA-I remains a serious problem

in the modern health care environment. Our

study suggests that surveillance programs are

effective in decreasing these infections, both

hospitalwide and among surgical patients. We

also confirm the increased mortality associated

with HA-MRSA-I. Further studies are needed

to aid in the reduction of the transmission of

this disease among hospitalized patients, with

particular focus on African American patients

and those with increased lengths of stay.

1. Shorr AF. Epidemiology of staphylococcal resistance.

Clin Infect Dis 2007;45(Suppl 3):S171–S176.

2.

Cosgrove

SE, Sakoulas G, Perencevich EN, Schwaber

Race

White (referent)

—

MJ, Karchmer AW, Carmeli Y. Comparison of morAfrican American

1.31

(1.1, 1.55)

0.002

tality associated with methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia:

Hispanic

0.99

(0.77, 1.28)

0.15

a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36(1):53–59.

Asian

0.29

(0.07, 1.18)

0.10

3. Blot SI, Vandewoude KH, Hoste EA, Colardyn FA.

Other

0.65

(0.31, 1.38)

0.65

Outcome and attributable mortality in critically ill

patients with bacteremia involving methicillin-susLength of stay

1.05

(1.05, 1.06)

<.001

ceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus auIn the after cohort

reus. Arch Intern Med 2002;162(19):2229–2235.

4. Anderson DJ, Sexton DJ, Kanafani ZA, Auten G,

Surgery

No (referent)

—

Kaye KS. Severe surgical site infection in commuYes

1.33

(1.05, 1.70)

<.0167

nity hospitals: epidemiology, key procedures, and

Age

1.00

(1.0, 1.01)

0.3334

the changing prevalence of methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol

Sex

Male (referent)

—

2007;28(9):1047–1053.

Female

0.49

(0.39, 0.62)

<.0001

5. Hidron AI, Edwards JR, Patel J, Horan TC, Sievert

DM, Pollock DA, Fridkin SK; National HealthRace

White (referent)

—

care Safety Network Team; Participating National

African American

1.48

(1.45, 1.91)

0.0212

Healthcare Safety Network Facilities. NHSN annual

Hispanic

1.00

(0.69, 1.47)

0.7821

update: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated

with healthcare-associated infections: annual sumAsian

0.69

(0.17, 2.79)

0.5864

mary of data reported to the National Healthcare

Other

0.73

(0.27, 1.98)

0.5479

Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control

Length of stay

1.05

(1.03, 1.04)

<.0001

and Prevention, 2006–2007. Infect Control Hosp

Epidemiol 2008;29(11):996–1011.

6. Muto CA, Jernigan JA, Ostrowsky BE, Richet HM,

Jarvis WR, Boyce JM, Farr BM; SHEA. SHEA

prophylaxis for patients who screen positive, and adminguideline for preventing nosocomial transmission of multidrug-resistant

strains of Staphylococcus aureus and enterococcus. Infect Control Hosp Epiistering mupirocin calcium nasal ointment for all patients

demiol 2003;24(5):362–386.

regardless of screening status (16). MRSA infections at per7. Kallen AJ, Mu Y, Bulens S, Reingold A, Petit S, Gershman K, Ray SM,

cutaneous gastrostomy sites decreased from 12% to 29% over

Harrison LH, Lynfield R, Dumyati G, Townes JM, Schaffner W, Patel PR,

a 33-month period to 2% after a screening and decontaminaFridkin SK; Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) MRSA Investigation program was initiated. The protocol involved screening

tors of the Emerging Infections Program. Health care-associated invasive

MRSA infections, 2005–2008. JAMA 2010;304(6):641–648.

for MRSA from multiple sites, nasal treatment with mupiro8. Thompson RL, Cabezudo I, Wenzel RP. Epidemiology of nosocomial

cin, and daily skin decontamination prior to the procedure

infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Ann Intern

(17). MRSA infection rates among ICU patients decreased

Med 1982;97(3):309–317.

from 3.0% to 1.5% when enhanced cleaning procedures were

9. Parvez N, Jinadatha C, Fader R, Huber TW, Robertson A, Kjar D, Corneused in rooms previously occupied by patients with MRSA. A

lius LK. Universal MRSA nasal surveillance: characterization of outcomes

at a tertiary care center and implications for infection control. South Med

similar reduction in vancomycin-resistant enterococci infecJ 2010;103(11):1084–1091.

tion rates from 3.0% to 2.2% was also demonstrated (18).

10. Harbarth S, Fankhauser C, Schrenzel J, Christenson J, Gervaz P,

However, Camus and colleagues did not show a reduction in

Bandiera-Clerc C, Renzi G, Vernaz N, Sax H, Pittet D. Universal screening

MRSA acquisition in the ICU setting with more aggressive

for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at hospital admission and nosointervention protocols, including repeated MRSA screening,

comial infection in surgical patients. JAMA 2008;299(10):1149–1157.

11. Mera RM, Suaya JA, Amrine-Madsen H, Hogea CS, Miller LA, Lu EP,

contact and droplet isolation precautions, and decontaminaSahm DF, O’Hara P, Acosta CJ. Increasing role of Staphylococcus aureus and

tion with nasal mupirocin and chlorhexidine body wash for

community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections

MRSA-positive patients (19).

Female

86

0.56

(0.48, 0.65)

<.001

Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings

Volume 27, Number 2

Table 5. Odds ratio of screening positive for MRSA colonization

and of death for patients with health care–associated MRSA

infection

Category

Variable

Odds ratio

95% CI

12.

13.

P value

Screening positive for MRSA colonization

Surgery

No (referent)

Yes

Age

Sex

Male (referent)

Female

Race

0.53

(0.45, 0.62) <.0001

1.02

(1.02, 1.03) <.0001

—

0.77

White (referent)

—

African American

1.41

(0.67, 0.89)

0.0003

(1.21, 1.64)

0.0312

Hispanic

0.70

(0.53, 0.92)

0.0003

Asian

1.50

(0.81, 2.76)

0.2783

Other

1.31

(0.79, 2.17)

0.5250

14.

15.

16.

17.

Death for patients with health care–associated MRSA infection

All patients

Surgical patients

Before

3.27

(2.40, 4.46) <.0001

After

3.12

(2.12, 4.60) <.0001

Before

5.06

(3.12, 8.21) <.0001

After

4.84

(2.51, 9.32) <.0001

MRSA indicates methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

April 2014

18.

19.

in the United States: a 10-year trend of replacement and expansion. Microb

Drug Resist 2011;17(2):321–328.

Stenehjem E, Rimland D. MRSA nasal colonization burden and risk of

MRSA infection. Am J Infect Control 2013;41(5):405–410.

Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, Petit S, Gershman K, Ray S, Harrison

LH, Lynfield R, Dumyati G, Townes JM, Craig AS, Zell ER, Fosheim GE,

McDougal LK, Carey RB, Fridkin SK; Active Bacterial Core surveillance

(ABCs) MRSA Investigators. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus infections in the United States. JAMA 2007;298(15):1763–

1771.

Graffunder EM, Venezia RA. Risk factors associated with nosocomial methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection including previous

use of antimicrobials. J Antimicrob Chemother 2002;49(6):999–1005.

Gammon J, Morgan-Samuel H, Gould D. A review of the evidence for

suboptimal compliance of healthcare practitioners to standard/universal

infection control precautions. J Clin Nurs 2008;17(2):157–167.

Walsh EE, Greene L, Kirshner R. Sustained reduction in methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus wound infections after cardiothoracic

surgery. Arch Intern Med 2011;171(1):68–73.

Thomas S, Cantrill S, Waghorn DJ, McIntyre A. The role of screening

and antibiotic prophylaxis in the prevention of percutaneous gastrostomy

site infection caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther 2007;25(5):593–597.

Datta R, Platt R, Yokoe DS, Huang SS. Environmental cleaning intervention and risk of acquiring multidrug-resistant organisms from prior room

occupants. Arch Intern Med 2011;171(6):491–494.

Camus C, Bellissant E, Legras A, Renault A, Gacouin A, Lavoué S, Branger

B, Donnio PY, le Corre P, Le Tulzo Y, Perrotin D, Thomas R. Randomized

comparison of 2 protocols to prevent acquisition of methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus: results of a 2-center study involving 500 patients.

Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2011;32(11):1064–1072.

Impact of a surveillance screening program on rates of MRSA

87

Improving hospital staff compliance with environmental

cleaning behavior

Lilly Ramphal, MD, MPH, Sumhiro Suzuki, PhD, Izah Mercy McCracken, and Amanda Addai, MPH

Reducing the incidence of healthcare-associated infections requires

proper environmental cleanliness of frequently touched objects within

the hospital environment. An intervention was launched in June 2012

and repeated in February 2013 and August 2013 to increase hospital

room cleanliness with repeated education and training of nursing and

environmental services staff to reduce healthcare-associated infections

at Cook Children’s Medical Center. Random rooms were tested, staff were

trained about proper cleaning, rooms were retested for surface cleanliness, and preintervention and postintervention values were compared.

The percentage of cleaned surfaces improved incrementally between the

three trials—with values of 20%, 49%, and 82%—showing that repeat

training favorably changed behavior in the staff (P = 0.007). During the

study period, during which other infection control interventions were

also introduced, there was a decline from 0.27 to 0.21 per 1000 patient

days for Clostridium difficile infection, 0.43 to 0.21 per 1000 patient

days for ventilator-associated infections, 1.8% to 1.2% for surgical site

infections, and 1.2 to 0.7 per 1000 central venous line days for central

line–associated bloodstream infections.

he Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

estimated that in 2002, healthcare-associated infections

(HAIs) contributed to 1.7 million infections and 99,000

deaths; 33,269 infections were in high-risk newborns,

19,059 in well-baby nurseries, 417,946 among adults and children in intensive care units, and 1,266,851 in adults and children outside of intensive care units. The overall annual direct

medical costs of HAIs to US hospitals ranges from a low of

$28.4 billion to a high of $45 billion (after adjusting to 2007

dollars using the Consumer Price Index for inpatient hospital

services) (1–4). Prevention of HAIs could save an estimated

$5.7 to a high of $31.5 billion in inpatient hospital services.

For this reason, HAIs have been identified by the US Department of Health and Human Services as a top priority for cost

reduction. Over 11,500 healthcare facilities in all 50 states use

the CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network to track HAIs.

Thirty states and the District of Columbia require reporting of

HAIs using this network (1).

The CDC has documented that HAIs are caused by many

pathogenic organisms present on floors, bedding, mops, and

furniture in the hospital environment (1, 2, 5–8)—what the

T

88

CDC has called “high-touch points/objects” (HTOs). Through

clinicians’ hands and the environment, patients may be exposed

to pathogenic bacteria such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and enterococcus (6, 7, 9, 10). Several studies

have documented the importance of cleaning and disinfecting

and its impact in preventing transmission of pathogens from

the environment to providers and patients in a broad range of

US healthcare settings (2). This study evaluated whether training interventions would be effective in changing the behavior

in nurses and environmental services (EVS) staff in cleaning

patient rooms after discharge. Baseline results suggested that

several interventions were needed. The ultimate goal was to

decrease the rate of HAIs.

METHODS

This research was considered a quality improvement project and so was exempt from review by the institutional review board at Cook Children’s Hospital. After patients were

discharged from their rooms, a public health student entered

random rooms on the medical and surgical floors and lightly

swabbed HTOs with clear Glo Germ gel before EVS staff or

nurses performed routine cleaning duties in each room. The

staff was blinded with respect to which rooms were going to be

sampled for inclusion in the study. HTOs were marked with a

fluorescent marking gel (invisible to the naked eye) evaluated

with ultraviolet blue light and then interpreted with Ecolab

Recording software after the patients were discharged from the

rooms and before the staff came to clean. After the cleaning,

the HTOs were evaluated with blue light. If the gel mark was

completely wiped off, then the cleaning was recorded as pass. If

any surface gel was still present, then the cleaning was recoded

as fail. For trial 1, 747 random HTOs were sampled; for trial

2, 1322; and for trial 3, 2188. The percentage of clean surfaces

was calculated. This procedure was completed in June 2012,

From Cook Children’s Hospital, Fort Worth, Texas (Ramphal); and the Departments

of Environmental Health (Ramphal, Addai) and Biostatistics (Suzuki, McCracken),

the University of North Texas School of Public Health. Dr. Ramphal is now with

Blue Cross Blue Shield.

Corresponding author: Lilly Ramphal, MD, MPH, Department of Environmental

Health, University of North Texas School of Public Health, 3500 Camp Bowie

Boulevard, Fort Worth, TX 76107-2699 (e-mail: lramphal@yahoo.com).

Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2014;27(2):88–91

February 2013, and August 2013, following training for nurses

and EVS staff on infection control principles, HTOs, and methods for environmental cleaning and disinfecting.

Data were collected before and after the intervention for

each of the three evaluation periods. Statistical analysis was

performed offsite using an independent sample t test to compare the pre- and postintervention means of surfaces cleaned.

Pearson’s chi-square test was used to determine if there was a

relationship between the cleaning and training for each HTO

object individually. The overall percentage of cleaned surfaces

was compared among the three evaluation periods, and the

overall percentage of cleaned surfaces was compared by buildings and floor levels. The goal was to evaluate the relationship

between interventions and cleaning behavior from trial to trial.

The significance level was set at P = 0.05.

RESULTS

The Table and Figure show the proportion of surfaces cleaned

before and after the intervention for each of the three periods.

Overall, the proportion of surfaces cleaned increased incrementally from 20% in June 2012 to 49% in February 2013 and 81%

in August 2013 (P = 0.007, df 25). In the third trial in August

2013, when some preintervention values were already improved

based on prior and ongoing training, there were still significant

improvements for three HTOs—the toilet seat, flush handle,

and bedpan (P = 0.03, 0.003, and 0.027, respectively).

DISCUSSION

An important component to reducing the incidence of HAIs

is getting buy-in from the staff to address the importance of

labor-intensive cleaning of HTOs (9–12). This study shows that

ongoing training followed by blinded monitoring with transparent reporting of the results in a positive, engaging manner will

motivate staff to improve cleaning behavior. Intense strategies

to reduce HAIs were ongoing in the hospital during the period

from June 2012 to August 2013; therefore, it is not surprising

that the overall rate of HAIs decreased substantially. During the

study period, there was a decline from 0.27 to 0.21 per 1000

patient days for Clostridium difficile infection, 0.43 to 0.21 per

1000 patient days for ventilator-associated infections, 1.8% to

1.2% for surgical site infections, and 1.2 to 0.7 per 1000 central

venous line days for central line–associated bloodstream infections. Other strategies to reduce HAIs were implemented during

the same time period to increase healthcare providers’ awareness

of hand washing during procedures and to supply them with

better kits for line-changing procedures. What portion of the

Table. Percentage of high-touch objects cleaned before and after three training interventions

June 2012

High-touch room surfaces

Surfaces

tested (n)

Surfaces

Surfaces

cleaned (n) cleaned (%)

February 2013

August 2013

Surfaces Surfaces

Surfaces

tested (n) cleaned (n) cleaned (%)

Surfaces Surfaces

Surfaces

tested (n) cleaned (n) cleaned (%)

Bed rail

44

18

41.0

43

21

49

132∗

83

63

TV control

22

1

4.5

20

15

75

71

50

70

Tray table

24

21

88

24

15

63

99

92

93

IV pole (grab area)

19

2

11

19

10

53

99

70

71

120∗

83

69

Nurse call button

28

5

18

20

12

60

Bed angle button

Telephone

28

4

14

28

14

50

39

27

70

23

16

70

23

19

83

108

67

62

Bedside table handle

26

3

12

26

10

38

83

58

70

Game controller side

42

10

24

40

22

55

143

100

70

Cubby handle

48

5

10

48

23

58

131∗

92

71

Chair arm

82

17

21

78

42

54

176

100

57

Chair headrest

39

5

13

32

9

28

99

58

59

Diaper scale top

15

5

33

15

5

33

91

78

86

Diaper scale button

21

3

14

19

10

53

246*

192

78

Light switch

58

3

5

58

21

36

119

75

63

75

72

4

42

17

40

104∗

1

4

25

14

56

37

28

75

7

28

25

13

52

32

30

93

2

8

24

8

33

56

50

90

44

Door knob

47

2

Computer mouse

25

Computer table

25

Computer keyboard

24

Computer pull-out tray

Total

18

0

658

130

0

18

8

20%

627

308

49%

34

27

1900

1435

80

76%

*Grouped data

April 2014

Improving hospital staff compliance with environmental cleaning behavior

89

Figure. Percentage of high-touch objects cleaned after a training intervention for the three trial periods.

decrease in HAIs was due to environmental cleaning is difficult