World English and World Englishes

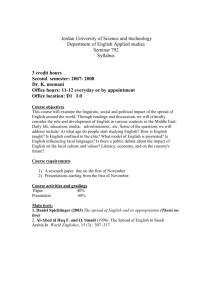

advertisement