Breaking the mould: new trajectories in the domiciliary care of... people in Ireland

advertisement

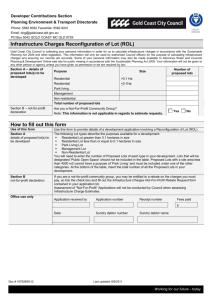

Breaking the mould: new trajectories in the domiciliary care of older people in Ireland Martha Doyle, Virpi Timonen School of Social Work and Social Policy, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. Key words: welfare mix, welfare pluralism, care regimes, quasi-markets, cash-for-care Running title: Breaking the mould Accepted for publication May 2, 2007 2 Abstract This article reviews the development of domiciliary care services for older people in Ireland over the last decade. It reveals three central developments, namely (1) the first steps, in the Irish context, towards a quasi-market; (2) the introduction of cash-for care and the subsequent notable segmentation of care tasks between the three sectors; and (3) a rapidly increasing reliance on for-profit private home care providers. The article concludes that while the Irish social care regime is still anchored in important ways in the primacy of informal (family) care and the subsidiarity principle, it has broken path-dependency by evolving towards an increasingly complex mix of public, not-for-profit and for-profit provision and financing. The most policy-relevant aspect of this new constellation is the lack of a regulatory framework that would enable the State to monitor the multiple and diverse providers with the view to ensuring the quality of home care services. 3 Introduction There is a paucity of research on the supply side of Irish domiciliary care; studies available have tended to focus on the not-for-profit sector and are now out-of-date. The most recent comprehensive overview of domiciliary care services for older people in Ireland was published in 1994 (Lundstrom & McKeown, 1994). While reference was made in this study to the emerging provision of public services via the newly-established role of health care assistant, the report focused almost exclusively on the not-for-profit sector, and at no point referred to the for-profit sector (unsurprisingly, since there were no more than one or two private providers operating in the country in the early 1990s). Our research, conducted in 2005–06, is the first study of the structures and operating principles of the formal domiciliary care services sector in contemporary Ireland (Timonen, Doyle & Prendergast, 2006). The intention was to gain a better understanding of the ‘division of labour’ between the public, private and not-for-profit sectors in the delivery and financing of home-care services for older persons, and of the parameters within which each sector operates. While informal (family) care and, increasingly, care delivered by (migrant) care workers operating in the grey market are of undoubted significance within the Irish context, they were outside the remit of this research which focused on the formal care sector only. The focus of this article lies in the key policy-relevant developments in the Irish domiciliary care services for older people, which are established via analysis of recent policies, on the one hand, and by teasing out the main organisational and operational characteristics of the three provider groups (public, private and not-for-profit), on the other. We also identify the main policy challenges that remain to be tackled in the Irish context if the complexity of the current 4 system is to be managed in a way that leads to the emergence of a more controlled and integrated system. Research methods More often than not, domiciliary care systems operate at the local or regional level rather than at the national level (Curtice and Fraser, 2000). Cognisant of both the national and regional diversity of domiciliary care services in Ireland, a mapping exercise of only the greater Dublin region was undertaken. This was justified, not only by the fact that this area contains almost one quarter of Ireland’s population, but also because the pluralism of service provision is most evident in this area. As was stated above, this was the first study of domiciliary care provision in Ireland since 1994; as such, we started from a very low level of knowledge about the sector which was compounded by the lack of a centralised system for collecting data about the provision of domiciliary services in the country, and the absence of suitable ‘ready-to-go’ sampling frames. As a first step in the research project, archival and desk-based research was carried out with the view to uncovering the evolution of the current system of domiciliary care services. Following this, 55 semi-structured interviews with 125 informants working in the area of home-care provision for older people in Dublin were conducted. These informants were drawn from the three ‘pillars’ of the public, private and not-for-profit sectors, and from the three ‘layers’ of care workers, their managers and individuals charged with planning and financial control of domiciliary care services (see Figure 1). The Dublin area is divided into eight local health offices (LHO) that have their own organisational and management structures. Senior public servants within these LHOs have 5 responsibility for the planning, (partial) funding and strategic provision of services in their respective areas. Across the eight LHO areas, 28 senior public servants working in the area of services for older people were interviewed. These interviews enabled us to map the services available within each area and to explore the interaction of key LHO personnel with both the not-for-profit and for-profit sectors that are part-funded by the state. In the case of the newest provider sector, the private home care sector the lack of a centralised registry on the sector meant that we had to start by establishing the number of operators in the Dublin area. The compilation of a contacts database of private providers, postal mail-out to these contacts and subsequent follow-up telephone conversations and snowballing enabled us to establish that 14 private home care organisations with a significant focus on older people operated in the Dublin area. A one-page postal questionnaire was dispatched to these providers, and completed by all but two of the organisations1. Interviews were conducted with directors from ten of these organisations representing approximately 70 per cent of providers in the Dublin area, and as such the data gathered at the level of company directors can be regarded as representative for that point in time. The not-for-profit sector is considerably older and larger than the private sector and, given the time constraints and qualitative nature of the interviews, we were not in a position to cover all the not-for-profit providers. However, we did interview 17 directors of the not-for-profit agencies (from a total of 28 not-for providers functioning in the Dublin area) which represents 60 per cent of the not-for-profit organisations in the Dublin area. While it could be argued that the data pertaining to this group are not ‘representative’ in the strictest sense of the word, we 1 These two providers delivered less that 25 per cent of their services to older people and were consequently omitted from the research. 6 observed a saturation of themes and a high degree of consistency regarding the key issues raised at both the management and operational levels. Using a semi-structured interview schedule the interviews with the for-profit and not-for profit home care directors explored the background, remit, structure and focus of the organisations along with their relationship with the Health Service Executive (HSE), the central government agency that channels funding via the LHOs. At the workforce level, 63 interviews were conducted with the not-for-profit (n=20), for-profit (n=23) and public sector care workers (n=20). The interview schedule used with this cohort covered the topics of training and qualifications, social security entitlements, work conditions, relationships with clients and employers and the perceived challenges and problems of their job. Data analysis was done both manually and with the aid of the QSR N6 qualitative data analysis software programme. Dominant themes were identified within each of the prespecified interview schedule categories and cross-checked by the researchers. The article at hand draws for the most part on the interviews conducted at the higher management levels (the top layer in the figure below)2. Insert Figure 1 here Research findings An analysis of the evolution of the domiciliary care sector frequently illustrates how institutional forces, cultural factors and church-state relations have had an important impact 2 Timonen and Doyle (2007a) offer a detailed analysis of the differences between the three sectors and draw on interviews across the three sectors and layers. 7 on the development of service provision (Bahle, 2003). In Ireland formal care services evolved from a reliance on charitable provision (Table 2, Stage 1) to public provision of institutional care (Table 2, Stage 2), to a greater home care focus based on religious and notfor-profit (voluntary) provision (Table 2, Stage 3), to a complex mix of limited public provision and state-funded not-for-profit (now largely secular) and for-profit sector provision (Table 2, Stage 4). A constant feature throughout this development was the dominant role of family care3 and, in the post-independence era, the increasing emphasis on subsidiarity4 (see Timonen & Doyle, 2007b, for detailed discussion of this historical evolution). Insert Figure 2 here We will now turn to discussing the three recent key developments in the Irish domiciliary care sector that were identified on the basis of the documentary and interview analysis, namely (1) the first steps, in the Irish context, towards a quasi-market, (2) the introduction of cash-for care and the subsequent notable segmentation of care tasks between the three sectors, largely resulting from the differing ways the state channels funding to the three sectors, and (3) the rapidly increasing reliance on private sector providers. 3 While Ireland shares many of the trends that are evident in other countries, it has not to date expanded the incentives for informal care as strongly as for instance Germany has done. This is somewhat surprising in the context of a strongly familialist system. 4 The subsidiarity principle in the context of social care dictates that care should be provided, whenever possible, by the social unit closest to the person in need of care. In the first instance, this means the family and other informal carers, and following them (religious) voluntary organisations. Only when these organisations have reached their limits should the state intervene. To this end, not-for-profit organisations received special treatment by the Irish State (via so-called Section 65 grants) and to this day are the dominant suppliers of domiciliary care services for older people in Ireland (Donoghue, 2001). 8 Transition towards a quasi-market, Irish style Quasi-markets have become an increasingly prominent feature of the social care systems of several European countries5. In a pure market transaction, ‘consumers come to the market with their own resources which they use to purchase the goods and services they require’ (Propper & Le Grand, 1997: 5). In a quasi-market, on the other hand, ‘purchasers funded by general taxation buy services from providers. The purchases may be the service users themselves, but more commonly, they are agents appointed by the state to purchase on behalf of the end-user’ (Propper & Le Grand, 1997: 7). Proponents of the introduction of quasi-markets purport that they ensure more efficient delivery of services, encourage competition, improve consumer choice, autonomy, quality of domiciliary care services and enable the public authorities to co-ordinate and regulate service provision more objectively. Practical issues such as resource constraints, recruitment difficulties and inadequate specialisation of services have also been advanced as reasons behind the new trend of out-sourcing and privatisation (Bahle, 2003). Regulations and quality standards for the providers are usually specified at either a national or regional (local authority) level. Typically, service providers document the suitability of their companies in terms of staffing and monitoring arrangements and generally will be accepted only if they 5 Examples of the introduction of such quasi-markets include the passing of the Community Care Act in England and Wales in 1993, which originally mandated local authorities to sub-contract 85 per cent of their services to the not-for-profit and private sectors (Curtice & Fraser, 2000; Wiener & Evans Cuellar,1999); the passing in 2003 of new legislation in Denmark that enabled private domiciliary care providers to compete with public sector providers (Rostgaard, 2004);; and Germany’s Long-Term Care Insurance programme introduced in 1994 which actively encourages service provision by the for-profit and not-for-profit sectors over public providers (Bönker & Wollmann, 2005). Common among all these countries is the change in the emphasis in the role of the public authorities, from the provider of services to the purchaser of services. 9 offer their services within a specified price range.6 Under such arrangements, it is assumed that service providers will be forced to offer better quality and more competitive services or exit the market.7 While the introduction of quasi-markets is not as explicit in the Irish context as in many other countries, new methods of contracting-out care and engaging in competitive tendering processes are increasingly observable. Direct tendering-out of care contracts, in addition to the channelling of finances via the home-care grants packages to private providers, is being piloted in one LHO area. The introduction of the cash-for programme (as discussed below) has also introduced a new market system, whereby the LHO draws up a list of ‘approved providers’ from which individuals who are given a home-care package (i.e. a sum of money to be spent on care) choose. At present the Irish home-care market is largely disorganised and unregulated. However, the entry of private providers to the publicly funded home care market has led to increased attention on the issue of accountability and documentation. Private providers that liaised closely with the HSE were more likely to raise concerns about the lack of regulation of both the private home care industry and the not-for profit sector. These providers frequently 6 Frade and Darmon (2005) argue that such measures create a ‘bureaucratic burden’ for the small local providers, and favour the larger national providers and in some areas have threatened the viability of the traditional domiciliary care services rooted in the local community. Economists, however, would argue that competition between providers ultimately benefits the consumers [care recipients], because the system allows the consumer to choose and shift to providers that offer the best service (Hirschman, 1970). 7 Research on this is not conclusive. For example Ranci and Pavolini (2006), who conducted a comparative analysis of the long-term care systems in France, Germany, Italy, UK and The Netherlands, concluded that while the introduction of social markets did improve consumer power, much of the power still resided in the public sector, with possible negative consequences for some of the providers or indeed the degree of competition possible between them. 10 reiterated the importance of ‘accountability’, transparency’ and ‘quality assurance’, and called for regulation in the form of monitoring, training and the payment of care workers’ social security and insurance coverage: There are a lot of agencies out there that I would call matching agencies… We are trying to get the government to regulate what’s going on, cause in that scenario there’s no training, there’s no supervision, there’s no background checks… We think there’s a Leas Cross scenario [this is the name of a nursing home that attracted considerable media and political attention following a documentary showing abuse of residents] out there in home care. [Director, for-profit home care company] Grievances about the unequal playing field in which the private home care sector and the notfor-profit sector compete was voiced by a number of private home care directors who argued that their higher service fees result from better trained and supervised staff. Many believed that they have higher overhead costs than the not-for-profit organisations and that the government should cover some of these costs, including the cost of carer training. These directors called for a more market-driven home care sector, which would end what they regarded as the comparative advantage levelled to the not-for profit sector through the allocation of funding via section 65 grants8. The introduction of quasi-markets within the Irish care sector has not been an explicit ambition of senior mangers within the HSE, however resource demands and capacity constraints have meant that by default the evolution of a more pluralistic provider landscape is becoming more evident. Senior LHO managers interviewed acknowledged the long 8 As stipulated in the Health Act 1953. 11 tradition of co-operation between the not-for-profit sector and HSE, but had ambivalent views on whether or not this privileged relationship would continue. The majority of these managers indicated that while in principle they would prefer to contract all of their care requirements to the not-for-profit organisations, since they were ‘linked more closely’ to the HSE structures, many organisations did not have the required capabilities or resources. Concern was voiced that some not-for-profit providers are not interested in expanding their services or delivering their service in the most efficient manner, and the belief that private providers would have to fill this void in the care market was common. When the interviews probed into the reasons for using private sector providers (rather than not-for-profit providers), the interviewees at the LHO level justified this by referring to the ‘critical mass of resources’, the more ‘professional’ management of the private sector companies, their greater ‘flexibility’, the ‘clear contracts’ with care workers and the ‘quicker’ processing of background checks. Although some LHO managers interviewed noted concerns about particular private sector companies that continue to act as intermediaries to care workers who are in principle ‘self-employed’ but remain outside the tax and social security net, several also cited reliability, training, insurance status, flexibility and ability to offer a 24hour service 7 days a week as distinct advantages of the private sector. However, adequate supply of quality private care services was not available within certain LHOs, with some LHOs personnel intimating that they are having difficulty finding adequately trained and insured private home-care providers. In light of the recent transformations within the care sector and new business relations particularly with private providers, there was a recognition at LHO management level that more formalized improved accountability mechanisms were required for both the private 12 sector and not-for- profit sector. A prevalent sentiment was that the current disorganised care market would ultimately have to be better organized and moderated, which would likely introduce a more clearly defined quasi-care-market as visible in other European countries. Introduction and impact of cash-for-care A key development in the provision of domiciliary care services in Ireland came about in 2001, when the Department of Health acknowledged that the existing arrangements were not sufficient to successfully support home care, and encouraged the Health Boards to pilot homecare grant schemes (Timonen, 2004). The provision of additional funding has largely been a consequence of the lack of adequate community care, which is currently leading to large numbers of older people using acute hospital facilities after their discharge date i.e. as longterm care (HSE, 2002). Home-care grants (or home-care packages) were envisaged to complement, not replace, the existing provision of services via the public sector and not-for-profit organisations. However, the rate at which home care packages have been introduced and expanded since 2001 suggests that in some areas they are replacing rather than complementing the work of the not-for-profit sector (Timonen, Convery & Cahill, 2006). Different funding mechanisms exist for this cashfor-care programme; in some areas prospective payments are made directly to recipients (allowing them to choose their own providers of care), in others care recipients choose a provider from a list of ‘approved’ private providers, while in other areas services are delivered by pre-contracted private or not-for-profit providers. By the first quarter of 2006, 952 homecare grants were being funded by the Health Service Executive in the Dublin area, compared with 192 in 2003. 13 The private sector has been the main beneficiary of the move towards cash-for-care, and growth of this sector is largely driven by this public funding mechanism, rather than by direct private spending on care. In contrast, the extent to which the not-for-profit organisations have embraced the home-care package funding stream varies. Some organisations interviewed restructured their business to accommodate these packages, while others took on only a handful of home-care package clients or considered the delivery of home-care packages (often requiring care provision ‘out-of-hours’ or at weekends) to be outside their capacity. A number of the not-for-profit managers were critical of their current unstable relationship with the HSE which has been exacerbated by the introduction of home care packages. Many not-for profit directors suspect that the HSE is attempting to introduce new business arrangements between the state and the not-for-profit sector which could potentially jeopardise their viability and serve to advantage private home care companies. Furthermore, a number of the not-for-profit sector representatives interviewed stated that a lack of HSE investment to cover administrative, management and support staff costs makes it more difficult to compete with the private sector and provide more flexible round-the-clock care as required through the home care package scheme. Increasing reliance on private sector providers The private home-care sector first emerged in Ireland in the late 1980s/early 1990s. This sector had not been explored prior to our research, but anecdotal reports suggest that the sector was in a constant state of flux until the introduction of publicly financed home-care packages that resulted in an expansion of demand for private sector care services. At the moment the private providers do not have to engage in open competitive tendering. Instead, contracts are allocated either on an ad hoc basis directly from the health services administration (the HSE via the LHOs) to the private sector companies who meet basic 14 minimum criteria, or indirectly via the ‘consumer’ who, once entitled to funding through a care package, can choose the provider that best meets his/her needs. For all but two private providers interviewed, the HSE home-care packages are the main source of their clientele, which in turn means that they are strongly, if only indirectly (via their clients), reliant on public funding. Presently the ‘market share’ of the private sector when compared with the not-for-profit organisations is small. However, a majority of the directors in this sector expressed confidence that thanks to government plans to expand the cash-for-care programme their client base has the potential to expand strongly: We would expect to be caring for about 5000 individuals in about 5 or 6 years…my expectations have gone higher now than the day we started in terms of how quick we can expand and how much the service is needed. Effectively I would expect to have 20 offices throughout Ireland… [Director, for-profit home care franchise] This increase in the role of the private sector should be put into the context of developments in the public and not-for-profit sectors. Direct delivery of public domiciliary care service is very limited in Ireland and takes place via the Health Care Assistants (HCAs), who deliver non-paramedical personal care to older people in their home. The main rationales for the introduction of HCAs in 1994 were the increasing demands on Public Health Nursing teams in the community and the realisation that a different kind of care worker (non-medical) was needed to provide personal care. In the Dublin area, there are approximately 85 healthcare assistants. This number is far from adequate, but recruitment difficulties and ceilings on staff numbers in the public sector mean that the LHOs have not been able to increase their numbers 15 over the last half decade, and consequently demand for this service outstrips supply. As one director of public health nursing put it, We ran a twilight service for years but because we did not have enough staff, the [care staff] were exhausted so the scheme was phased out. Subsequently the decision was made that unless the person is terminally ill such a service would not be offered. For such a scheme to be viable, you need a dedicated team. The not-for profit sector is currently (and has been since the mid 1950s) the predominate and largest provider of publicly funded domiciliary care. The not-for-profit home-care sector in Ireland is frequently referred to as the ‘voluntary home-care/help sector’. However the introduction of the minimum wage in 2000 and subsequent professionalisation of the workforce means that the title ‘voluntary’ home-care service is a misnomer and should be replaced with the term ‘not-for-profit’ home-care service. . The Health Service Executive provides the bulk of the funding for these organisations as outlined under section 65 of the Health Act 1953. Approximately 1.25 million home-care hours are provided by the 28 notfor-profit home care organisations in the Dublin area annually (administrative figures obtained from the Department of Health and Children). The distribution and allocation however, of these home-care hours varies considerably across the different LHO areas, largely reflecting the unsystematic and uncoordinated funding relationship between the HSE and these providers. Traditionally, and still in some areas, the not-for-profit providers deliver only domestic care, although recent organisational changes within this sector has seen an increasing number of care staff (particularly in the larger organisations) working in a dual capacity, delivering both personal and domestic care . 16 Policy implications Our research illustrates that the Irish domiciliary care mix has changed substantially in the past five years. While not-for-profit providers are still the predominant suppliers of statefunded domiciliary care, the private sector has managed to fill an important niche in the home-care market, which neither the not-for-profit nor public sector have been able, or allowed, to supply. The new cash-for-care policy (home-care packages) is the main driver behind this change, and illustrates the powerful role that public financing plays in altering the profiles of providers and their respective positions of power or weakness. Specialisations of the three sectors are to a large extent the result of the differing ways in which the state has channelled funding to the three sectors. Whereas funding for the not-for-profit sector is retrospective, i.e. largely based on past delivery of a certain number of home help hours, private sector agencies and companies ‘bid’ for a set of care packages, or for inclusion in a list from which care recipients choose their service providers. The manner in which funding is channelled to the two sectors, therefore, creates a strong incentive for the private sector to be as flexible as possible, whereas not-for-profit organisations are constrained and ‘disincentivised’ by the retrospective nature of the funding arrangement. Because both the not-for-profit and for-profit provider organisations are able to operate in a complete or partial ‘vacuum’ in terms of policy guidelines and regulations, they have diversified and established their own procedures and protocols for areas such as staff qualifications and quality controls, tax compliance, hiring and contractual practices, and insurance. The extent to which individuals and organisations are left to ‘make up rules as they go along’ is illustrated by the following quote from an interview with a LHO representative: 17 We are chasing some of the larger private care agencies and trying to use those who have insurance and some form of training for their employees, but again no-one is checking up on them as such. The way it is going and we use one or two agencies, it will cost a lot and we’ll have to go to tender and we’ll have to draw up standards about how an agency inducts and trains it staff … the push has just been to discharge people from hospital … these things will have to come into play. If the current funding arrangements are maintained, it is likely that the not-for-profit sector and the private sector will continue to evolve along different paths. In a more regulated and service user-driven alternative (such as those in operation in Denmark and Germany), any provider that meets quality, training and monitoring requirements would be free to offer their services to individuals who are given entitlement to services (see Doyle and Timonen, 2007). The pivotal issue in this regard is the regulation of services and the creation of a level playing field that draws out the strengths of different providers and ensures a greater degree of consumer direction and quality control. Undoubtedly, additional oversight and monitoring of public monies invested in both the private and not-for-profit home care sectors will have to be enforced. However, policy makers have a difficult task in formulating these monitoring procedures. It seems probable that increased regulation of the not-for-profit and for-profit sector will have substantial financial ramifications. Increased regulation in the form of mandatory training and supervision will mean higher overheads for the state, particularly in the current environment where the forprofit providers intimate that they are not prepared to cover the costs of training themselves. Furthermore, it will have to be established whether training and monitoring requirements shall be universal among private, public and not-for-profit employees alike, what realistic and 18 desirable minimum training standards are for care workers, and also whether these standards are applicable to all carers even if they only deliver domestic care. Whether or not the state will continue to support the position of the not-for-profit organisations is unknown. Currently their generic budgets are separate from the home-care package budget, but it is difficult to surmise whether these funding streams will continue to remain separate or merge in the coming years. The stated intention by the government to extend and roll out more home care packages may have negative ramifications for the not-forprofit organisations if they continue to be awarded in the present uncoordinated fashion. One plausible alternative that would protect the not-for-profit organisations is that the state will continue to fund their generic budget enabling them to continue to deliver domestic care and low-level personal care and contract-out more intensive personal care to the for-profit sector. However, even if this is the case, it is probable that more formal standardised service level agreements will be negotiated with the not-for-profit providers. The ‘care mix’ of public, profit and not-for-profit providers is likely to evolve, given the complexity of the problems of older people living at home and the projected rise of older people in the population. It is estimate that the demand for domiciliary care in Ireland will increase by 100 to 215 per cent by the year 2051 (Hughes, Williams and Blackwell, 2005). Such a rises in the demand for domiciliary care services, coupled with fiscal pressure at a national level, could result in a rationing or targeting of services to those deemed most in need. If publicly funded care is delivered only to older people with extensive care needs, it would seem that the requirement for dual capacity carers, as currently available in the private sector and available only to a limited extent in the not-for-profit sector, will be required. Were this to happen, the majority of the not-for-profit organisations would have to radically re- 19 structure or cease to operate. In such a scenario, persons with less extensive care needs would be left without any public assistance and therefore have to rely on informal family care, the private sector or care obtained via the grey market. In the light of experience in other countries that have embraced quasi-markets in the care sector, it appears that the central issue of quality is not straightforwardly related to a pluralism of providers. From both the perspective of the recipient and the care worker, quality has been found to correspond more closely to the amount of time the carer is allowed to spend with the client, the ability of the recipient to direct the work of the carer (Stack & Provis, 2000; Staehr, 2005) and the age and employment conditions of the care worker (Netten, Sandhu & Francis, 2006). Independent budgets are currently being piloted in 13 local authorities in the UK (Glendinning, 2006). In the UK context, this signifies a departure from quasi-markets to a more open market system where the care recipient instead of a ‘third party proxy’ chooses both the care tasks (including transport and help with leisure and recreational activities) and the service provider (including informal carers, pet minders, taxi drivers or other service provider of choice). The strengths and weakness of this new care arrangement are currently under review across five universities in the UK (www.ibsen.org). Preliminary analysis from this project elucidates the complexity of these new care systems particularly for frail or cognitively disabled persons, but also reflects the growing awareness that care recipients want to actively control their own care arrangements (Glendinning, 2006). In Ireland it is highly probable that the debate on both the dis/advantages of opening up the care market and offering greater consumer choice to home-care recipients will continue into the foreseeable future. Whatever the outcomes of this debate, it is imperative that the state does not relinquish its responsibility to monitor, the delivery of home care services that it finances both 20 directly and indirectly, the level of competition between the various providers, and the ability of providers to compete as a consequence of quality and cost stipulations.. Conclusion This article has illustrated how the current form of the domiciliary care sector in Ireland is more the result of gradual evolution than systematic planning. The rise of the private homecare sector over the last decade is a highly significant development that has its origins both in the limited funding made available to the public and not-for-profit sectors and in the increased emphasis on cash-for-care (Timonen, Convery & Cahill, 2006). The channelling of public funds to private companies is therefore the newest and still evolving manifestation of the state’s role in the delivery of domiciliary care services and arguably one that has new and different implications from the point of view of monitoring and quality controls. As Bahle (2003) argues, forces such as privatisation and decentralisation are not necessarily the antidotes of integration and control of social care systems. In the case of Ireland, too, it is possible that more integrated and better controlled systems of home care will emerge from the current highly complex and unregulated system. Lastly, the complexity of home care also poses a challenge for regime theorists. A good regime classification is able to serve as a useful simplification of reality. The question must be asked: Is it possible to construct social care regime classifications on the basis of the kind of complexity that is evident in the case of Ireland and many other countries where the state both provides and finances care, increasingly through a multitude of private and not-for-profit organisations that exist alongside informal and grey market provision of care? While much valuable work has been done by those attempting to construct such classifications (e.g. Anttonen & Sipila, 1996), the area of social care has rapidly become more complex, and the 21 classifications developed in the not too distant past are arguably already out of date. The task of developing social care regime classifications that serve as useful simplifications of the complex reality poses a great, and perhaps insurmountable, challenge to social scientists. References Anttonen A, Sipilä J (1996). European Social Care Services: Is it possible to identify models? Journal of European Social Policy 6(2): 87–100. Bahle T (2003). The changing institutionalisation of social services in England and Wales, France and Germany: is the welfare state on the retreat? Journal of European Social Policy 13(1): 5–20. Bönker F, Wollmann H (2005). Public Sector Reforms and Local Government in Germany: The Case of Local Social Policy. In: Hoffmann-Martinot V, Wollmann H, eds. Comparing Public Sector Reforms in France and Germany. VS, Wiesbaden. Curtice L, Fraser F (2000). The domiciliary care market in Scotland: quasi-markets revisited. Health & Social Care in the Community 8(4): 260–268. Donoghue F (2001). Volunteering in the Republic of Ireland: History, Socio-Economic Context and Meaning. Paper presented at Tipping the Balance Conference UN International Year of Volunteering 2001. Doyle M, Timonen V (2007). Home Care for Ageing Populations. A comparative analysis of domiciliary care in Denmark, Germany and the United States. Cheltenham, Edward Elgar. Frade C, Darmon I (2005). New modes of business organization and precarious employment: Towards the recommodification of labour? Journal of European Social Policy 15(2): 107– 121. Glendinning C (2006). Improving choice and control in support for older and disabled people: what are the implications of new developments in England? Paper Presented at the XVI ISA World Congress of Sociology 24 June to 29th July, Durban, South Africa. Health Service Executive (2002). Acute Hospital Bed Capacity: A National Review. Dublin, Stationery Office. Hirschman AO (1970). Exit, voice and loyalty. Harvard University Press, Cambridge. Hughes G, Williams J, Blackwell S (2005). Demand and cost of long-term care services, Country report: Ireland. Dublin, GALCA project publication, Economic and Social Research Institute. 22 Lundstrom F, McKeown K (1994). Home Help Service for Elderly People in Ireland. Dublin, National Council for the Elderly. Netten A, Sandhu J, Francis J (2006). Home care workers and quality of care. Paper presented at the XVI ISA World Congress of Sociology 24 June to 29th July, Durban, South Africa. Propper C, Le Grand J (1997). Central Government and Quasi-Markets: The Case of Health Care. Discussion Paper No 6. The London School of Economics and Political Science. Ranci C, Pavolini E (2006). New trends of elderly care policy in Western Europe: towards a social market of care services? Paper Presented at the XVI ISA World Congress of Sociology 24 June to 29th July, Durban, South Africa. Stack S and Provis C (2000). Tensions in flexible employment agreements for caring labour. Proceedings of 14th AIRAANZ Conference, ed. Burges, J. and Strachen, G, vol.2 p162 171 Staehr K (2005). Integration inden for social- og sundhedsområdet [Integration in the areas of health and social welfare]. Forbundet af Offentigt Ansatte, Denmark. Rostgaard T (2004). The construction of consumerism – Free choice of care for the elderly in Denmark. Paper presented at the Symposium ‘Consumerism of care for the elderly’. The Danish National Institute of Social Research (SFI), Copenhagen, 30 August 2004. Timonen V (2004). Evaluation of Home care packages. Eastern Regional Health Authority, Dublin. Timonen V, Convery J, Cahill S (2006). Care revolutions in the making? A comparison of cash-for-care programmes in four European countries. Ageing and Society 26(3): 455– 474. Timonen V, Doyle M (2007a, forthcoming). Worlds Apart? Public, Private and Non-Profit Sector Providers of Domiciliary Care Services for Older People in Ireland. Journal of Aging Studies. Timonen V, Doyle M (2007b, forthcoming). From the Workhouse to the Home: Evolution of Care Policy for Older People in Ireland. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. Timonen V, Doyle M, Prendergast D (2006). No Place Like Home: Study of Domiciliary Care Services for Older People in Ireland. Dublin, Liffey Press. Wiener J M, Evans Cuellar A (1999). Public and Private Responsibilities Home-and Community-Based Services in the United Kingdom and Germany. Journal of Aging and Health 11(3): 417–444. 23 Figure 1. Interview matrix and breakdown of interviews in each sector. Matrix of Persons Interviewed Public Sector Private Sector Non-Profit Sector Planning and Financing (LHO Managers of Services for Older People and Directors of Public Health Nursing) Operational Management (LHO personnel above, Home Help Organisers and Private Agency Directors) Care Workers (Health Care Assistants, Home Helps and Private Care Workers) Public Private Not-for- Total Profit 28 n/a n/a 28 2 (+9) 11 21 34 Delivery 20 23 20 63 Total 50 34 41 125 Planning /Financial Management 24 Figure 2. Historical evolution of formal elder care services in Ireland.

![Domiciliary Care leaflet editted_new.doc[...]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007119587_1-e85760c65789a5d1ecb4c83918ba0905-300x300.png)