HIGH SCHOOL TRACKING AND SOCIAL CAPITAL AMONG COLLEGE-BOUND STUDENTS Samuel Cruz Velázquez

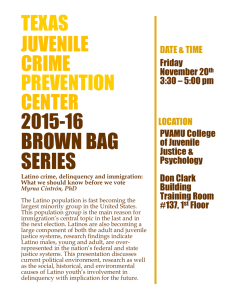

advertisement