CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE

advertisement

~··

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE

SKIN CONDUCTANCE PATTERNS AMONG

n LEARNING DISABLED STUDENTS

A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the

requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 111

Special Education

by

Gail Beth Werbach

June, 1979

~··

The Thesis of Gail Beth Werbach is

~pproved:

Ruth \Forer, Ed.D.

~~a Wyeth, Ed.D.

(__§r~

Lee, Ed. D. , Chairperson

California State University, Northridge

ii

Dedication

To My Husband, Hel vyn vJerbach, without whose

love and guidance this would not have

been possible.

iii

TABLE

OF

CON'rENTS

.................................

ii

Dedication . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . .

iii

Abstract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Vl

Approval page

I

INTRODUCTION

Background of the Problem.................

Statement of the Problem..................

Research Hypothesis.......................

Purpose of the Study......................

Definition of Terms.......................

II

IV

3

3

3

4

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Activation Theory .. . ...... ...•........ ...

Galvanic Skin Response....................

Attention and the Learning Disabled Child.

III

2

7

9

20

METHODOLOGY

Pilot Study. . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

22

Statistical Design........................

Null Hypothesis. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . • . . .

Subjects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ~ . . . . . . . . .

Procedures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . .

Instrumentation ........................ ·. . .

Data Collection and Recording.............

Data Processing and Analysis..............

Methodological Assumptions................

Limita·tions...............................

24

24

2425

26

31

34

37

37

ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION

Findi11.gs. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Discussion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .-...............

Interpretation............................

iv

40

42

44

Table of Contents (Continued)

V

SUMMARY, CONCLUSIONS,

RECOMMENDATIONS

·,

Summary. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ·...........

Recomrnendat ions . .... ·. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

47

48

48

References... . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

49

v

ABSTRACT

SKIN CONDUCTANCE PATTERNS AMONG

LEARNING DISABLED STUDENTS

by

Gail Beth Werbach

Master of Arts in Special Education

Learning-reading Disorders

This study was designed to explore the relationship

between activation and learning among the learning disabled by utilizing electrodermal patterns of response as

the measure of activation and a paired-associates task as

the measure of learning.

A review of the literature yielded a number of studies

relating activation to learning among normal achieving students, but few studies were found which explored this relationship among the learning disabled.

The Research Hypothesis was: Is performance on a pairedassociates task for learning disabled childreri related

t~

active.tion of electrodermal activity as measured by skin

conductance levels?

The

subj~cts

vi

studied were forty-four

children betv1een the ages of five and fifteen referred to

the Department of Mental Health of Ross Loos Medical Group

in Los

A~geles

for the evaluation and/or treatment of learn-

ing problems.

The statistical design used was a 2x2 Factorial Design.

Measurements consisted of number correct on a paired-associates task as index of learning and skin conductance levels

taken on a Toomin GSR instrument as index of activation.

Levels of skin conductance immediately following presentation of the learning task were selected for statistical

analysis.

.05 level.

The Chi Square analysis was significant at the

Subjects with a moderate level of skin

conduc~

tance (0.6-1.1 log micromhos) were more likely to perform

better than subjects with either lower or higher levels of

skin conductance.

This study has identified a subgroup of the learning

disabled population whose abnormally high or low levels of

skin conduc·tance reflect their problems in learning .

..

VI,-

CHAPTER I

Introduction

In the last ten years, educators have shown increasing

concern over the problems of learning disabled children.

These children show a marked discrepancy between their

potential for academic achievement and their actual school

performance.

Those educators and psychologists who study

these children have difficulty formulating a concise definition of what constitutes learning disability.

Clements

(1966) found 38 terms 1n the literature for children with

learning disabilities and associated symptoms.

The follow-

ing definition by the National Advisory Committee on Handicapped Children is probably the one most commonly used to

identify pupils who are eligible for special education placement and related services:

Children with special learning disabilities exhibit

a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological

processes involved in understanding or in using

spoken or written languages. These may be manifested

in disorders of listening, thinking, talking, reading,

writing, spelling, or arithmetic. They include conditions which have been referred to as perceptual

handicaps, brain injury, minimal brain dysfunction,

dyslexia, developmental aphasia, etc. They do not

include learning problems which are due primarily to

visual, hearing or motor handicaps, to mental retardation, emotional disturbances or to environmental disadvantage.

{Myers & Hammill, 1976, 3-4).

1

2

The reported prevalence of learning disability varies

greatly depending upon the definition and the specific

criteria employed, and ranges from one to thirty percent of

school children in published studies (Myers & Hanunill,l976).

Background of the Problem

Observers of the learning disabled child in a classroom

setting commonly note behavioral criteria by which these

children can be separated from others with similar potential

who perform adequately.

These include hyperactivity, dis-

tractibility, short attention span and perceptual motor

deficits.

Researchers have sought to relate these behavior-

al symptoms to particular psychological or physiological

deficits.

Some of the studies assign a central role to

attentional and motivational processes (Tarver & Hallahan,

1974).

Others cite evidence that activation, as indicated

by a number of physiological measures, is related to both

intra- and inter-individual variations in performance (Berry

1962).

Hhen the degree of activation is minimal, perform- .

ance on any number of tasks is of mediocre quality.

As

activation increases to a moderate level, performance

reaches an optimal point.

When activation is very high, the

quality of performance again deteriorates.

Thus, when

activation is plotted against performance, a curve develops

which resembles an inverted "U".

Of course, the degree of

activation will be a function of both the characteristics

3

of the individual and the task being studied (Malmo, 1959).

Statement of ·the P:l?oblem

Do deviations from moderate activation levels of electrodermal activity correlate with difficulty in learning

among the learning disabled?

Research Hypothesis

The research hypothesis was:

Is performance on a

paired-associates task for learning disabled children related to activation of electrodermal activity as measured by

skin conductance levels?

Purpose of the Study

This study explores the relationship between activation and learning among the learning disabled by utilizing

electrodermal patterns of response as the measure of activation and a paired-associates'task as the measure of learning.

There are a number of studies in the literature concerning activation as related to learning among normal achieving

students, while little has been published concerning this

relationship among learning disabled.

The paucity of such

studies is unfortunate as they may assist in the identification of specific maladaptive activational patter•ns within a

sub-group of the learning disabled, who could then benefit

4

from therapeutic procedures designed to correct such

patterns.

Definition of Terms

,.....

Activation: A term used primarily to refer to the func-

tions of the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS).

This system regulates the level of general attention in relation to environmental stimuli on the one hand, and cerebral processes on the other.

Th~

organism is continually

in varying states of activation, or in an "activation con-'.

tinuum," and reaches its highest activation level at an

average stimulus intensity, whereas the level of activation

via the ARAS remains low at very intense and very weak

stimulation.

2.

Defensive Response:

According to Sokolov,(l960, 1963),

the Defensive Response (DR) is evoked by intense or noxious

stimulation and is extremely resistant to habituation.

Its

function is to protect the organism by attenuating the perceptual effects of .such stimulation.

Using only measures of

electrodermal activity, the occurrence of a DR is somewhat

difficult to differentiate from an Orienting Response.

Recently, Edelberg (1972) has suggested that measures of

electrodermal recovery rate may distinguish DRs from goaldirected behavior.

3.

Electrodermal Activity: Electrodermal activity is a

physiologic measure which indicates changes in sweat gland

5

activity.

Since the sweat glands are innervated by the

sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system, measures

of electrodermal activity also provide indications of sympathetic nervous system activity.

These measures include

skin conductance (or resistance) levels, skin conductance

(or resistance) responses and skin potential level and response.

They are often referred to as the "GSR" which stands

for Galvanic Skin Response.

4.

Learning:

A change in response due to experience.

English and English (1958) in their definition include

under learning "the process or processes whereby such change

is brought about."

5.

Learning Disability:

6.

Orienting Response:

see page 1.

Th~

concept of the orienting res-

ponse (OR) was described originally by Pavlov (1927) as the

··investigatory or "what-is-it" reflex.

Sokolov (1960, 1963)

has extended this investigation and developed a detailed

theory of receptivity to stimuli and information processing

based upon the occurrence of ORs and Defensive Responses.

He describes the OR as a generalized response to novel stimuli which are mild to moderate in intensity which habituates·upon repetition of the stimuli.

That response is characterized by a complex pattern of

skeletal and physiological changes and includes changes in

skin conductance as well as other autonomic and electroencephalographic responses.

Sokolov has taken the position

~···

6

that the OR functions to produce heightened sensitivity to

environmental stimulation causing increased intake and

processing of information.

7.

Paired-associates task:

A rote method used in verbal

learning and retention studies whereby a subject must learn

stimulus-response paired items, and later, upon request,

must reproduce the second item upon presentation of the

first remembered item.

The score is the number of successes

or of retained members.

Organization of the Remainder of the Thesis

In Chapter 2 a review of the literature related to the

study is presented.

The review includes pertinent informa-

tion on Activation Theory, Galvanic Skin Response and the

Learning Disabled Child.

of the study.

Chapter 3 details the methodology

Included is a descripti?n of the pilot study

which preceeded the ·experimental study.

This chapter also

includes the experimental design, procedures and instrumentation.

Chapter 4 contains an analysis and evaluation of

the study and discussion of the results.

Chapter 5 presents

a summary, conclusions and recommendations for further

study.

CHAPTER II

Review of Literature

Activation Theory

The terms "arousal," "energy mobilization," and "excitation" describe physiological processes which are currently

subsumed under "activation." Research by physiologists on

how the autonomic nervous system (ANS.) responds to lncreasing stimulation· and by electroencephalographer'S on the

patterns of electrical activity of the brain's cortical

cells under similar conditions has demonstrated that a

continuum of EEG patterns existed which paralleled a continuum of behavior from an extreme of deep sleep to an extreme of great excitement.

The electroencephalographers

called the EEG responses to stimulation "activation." Since

psychophysiologists use "activation" as 6ne of the terms

describing autonomic responses to stimulation, the word is

nmv in general use to refer to both EEG and autonomic

responses (Sternbach, 1966).

Activation may be influenced by stimuli.

It occurs

not only as a result of external stimulation; central phenomena, such as exciting

thoughts~

can produce similar effects.

Also it appears that stimuli acting through the classical

sensory

path~vays

as well as changes in activity in various

parts of the brain affect activiation through a common path-

7

8

way, the brain stem reticular formation.

Fibers from each

of the sensory systems, on their way to the cortex, send off

branches to the reticular formation as they pass through

the brain stem to produce a generalized cortical activation.

This reticular system seems necessary for activation; when

it is damaged by accident, disease, or experiment, the

individual is difficult or impossible to arouse, and is in

a coma ..

The possibility of ever-increasing activity, due to

stimulation of .the reticular formation which produces autonomic and muscular activity which then results in greater

reticular activity, is prevented by built-in mechanisms for

terminating the cycle.

Homeostatic-like processes (negative

feedback) operate in all such cortical-subcortical inter-

......

ac~.1ons.

The cortex, hypothalamus, reticular formation, per1pheral autonomic, motor and sensory fibers and circulating

hormones are all involved in activation.

All continuously

influence each other and modify each other's and their own

input.

The indices frequently used to measure changes in activation (short term fluctuation, or brief responses to some

form of stimulation) have relatively little lag, are quantifiable and have good reliability.

The electromyograph

(EMG) records traces of muscle action potentials given off

by contracting muscles.

The electroencephalograph (EEG)

9

records the electrical activity of the cerebral cortex which

reflects fluctuations in membrane potentials in the millions

of cortical cells, an ongoing metabolic phenomenon, not

action potentials resulting from specific stimulation.

The

Galvanic Skin Response (GSR), which is a measure of electrodermal activity (EDA) is another measure that is easily

recorded and quantified, and is a sensitive responder to

stimuli from both external and internal sources.

Other

measures of activation include heart rate, blood pressure

and respiratory rate.

Galvanic Skin Response (GSR)

A.

GSR As A Heasure of Activation

The use of measures of electrodermal activity (EDA) in

relation to the theoretical concepts of attention and arousal seems to have begun with the work of Fere (1888).

He

was interested in the effects of sensory and emotional stimuli on the development of "psychic·energy" and developed a

very early statement of arousal theory.·

Fere measured skin

resistance res?onses and demonstrated that sensory or emotional stimulation was accompanied by a decrease in skin

resistance.

The report by Fere repre.sents what appears to

be the first at-cempt to use EDA as an index of an important

psychological construct (Prokasy, 1973).

The early work of Fere led to what is knovm today as

arousal or activation theory.

Duffy took the position that

10

the general level of energy mobilization is a major aspect

of what has been historically labeled as emotion.

She

pointed to skin conductance level as an indicator of the

level of energy mobilization (Duffy & Lacey, 1946).

The

term "energy mobilization" was soon replaced by "activation"

which was put forth by Lindsley (1951, 1960).

Lindsley

showed that activation or arousal is related to activity 1n

the brain stem reticular formation and is manifested by in_creased frequency and decreased amplitude of EEG activity.

Sharpless and Ja_sper (1956) pointed out that the lower portions of the reticular formation are responsible for the

longer-lasting changes in the level of reactivity, whereas

the upper portions of the reticular formation seem to subserve attentive processes which are of briefer duration.

Malmo (1958) supported the position that tonic measures such

as SCL are the best indices of activation or general arousal.

A number of studies have shown that, when the degree of

activation is minimal, performance on any number of tasks is

of mediocre quality.

As activation increases to a moderate

level,·performance reaches an optimal point.

When activa-

tion is very great, the quality of performance deteriorates

to alow point again.

This sort of relationship is descri-

bed as the inverted U from the appearanceof the graph when

the degree of activation is plotted against level of performance.

Schlossberg (1953) first noted the curvilinear

relationship between activation and behavioral efficiency.

11

The concept has been further elaborated by Hebb (1955) and

Malmo (1958).

B.

GSR Parameters in the Measurement of EDA

There are a number of dependent variables which can be

obtained from recordings of EDA.

The different measures of

EDA have been used for a variety of purposes including (1)

the level of arousal, (2) the level of alertness or attentiveness, (3) the impact of different types and intensities

of stimulation, (4) the rate and amount of habituation of

responses as a function of different stimulus conditions,

(5) a means of differentiating ORs and DRs, (6) assessing

individual differences in responsiveness, attentiveness,

conditioning and anxiety, and (7) the investigation of

differences· among diagnostic categories.

The use of tonic levels of skin resistance (SRL), skin

conductance ( SCL), and skin potential (SPL) as indices of

the general level of activation goes back to the work of

Fere (1888).

Recent studies are consistent with the hypo-

thesis that SCL is a satisfactory indicator of the general

level of activation (Duffy 1962, Malmo 1959, Raskin 1969).

Liederman and Shapiro (1964) recorded SPL during different

stimulus conditions.

They reported that SPL was low during

sleep, intermediate during a monotonous learning task, and

high during the presentation of electric shock, noises, and

during sensory deprivation.

They concluded that SPL is a

12

simple, objective technique for measurlng various states

of behavioral activation.

In general, the amplitude of skin resistance responses

(SRR), skin conductance responses (SCR), and skin potential

responses (SPR) have been the most popular measures of EDA.

Studies employing phasic EDA's as dependent variables include investigations of variations in parameters of simple

stimuli (Davis 1955, Raskin 1969), measures of anxiety

(Martin 1961), and individual differences in attention

(Maltzman and Raskin 1965).

Unfortunately, procedures for measuring changes in EDA

have not been standardized.

Authors may report, for

example, any consecutive changes (Rugel 1971, Spencer 1973)

or may report' the. measure only at certain pre-arranged

intervals regardless of whether it has changes (Andreassi

1967, Hunter 1972, Johnson 1967).

Because of the lack of

stnadardization, it is often impossible to compare similar

studies.

C.

GSR And Attention

Historically, most approaches to the relationship bet-

ween attention, arousal, and performance have ignored individual differences.

However, in the past twenty years,

there has been increased interest in exploring such differences in autonomic activity and their relation to performance in a variety of situations.

13

One major line of investigation was initiated by John

Lacey and his co-workers.

That approach focused on the re-

lationships between individual differences in the rate of

nonspecific EDRs, performance, and personality variables.

'

Lacey and Lacey (1958) counted the number of non-specific

SRRs during a rest period, the performance of different

tasks and the presentation of electric shock.

They found

.high correlations across time and conditions, and they conc~uded

that the rate of non-specific SRRs is a stable indi-

vidual characteristic.

A second approach to the study of individual differences in EDA was derived from Sokolov's (1963) model of ORs

and DRs and is exemplified by the work of Maltzman and

Raskin (1965).

Their approach involves the use of an index

of individual OR amplitude as a means of predicting performance in situations such as semantic conditioning and

alization of SCRs (Raskin 1969),

ve~bal

gener~-

learning (Belloni

1964), and verbal conditioning (Smith 1966).

The general

procedure is to obtain a measure of the OR for each S by

measuring the amplitude of SCR to the first stimulus or

first USC presented to the S and then assessing the degree

of relationship between individual differences in the

amplitude of ORs and performance.

The data reported on the relationships between individual differences in electrodermal ORs and performance seem

to indicate that individual differences in amplitude of

14

electrodermal ORs are related to individual differences in

~ttentional

and learning capacities.

Belloni (1964) divided

her subjects into low-OR and high-OR groups and asked them

to learn lists of paired associates (PA).

She found that,

for male Ss, high ORs were associated with faster response

speed on difficult items and fewer trials required to reach

the criterion of learning.

obtained with female Ss.

Significant results were not

Thus, the results for male Ss

indicated that amplitude of electrodermal ORs are related

to performance in PA learning in a way which is predicted

by the attentional-perceptual capacity interpretation of

ORs.

Similar results were obtained by Maltzman and Raskin

(1965) and Raskin (1969).

A number of studies have assessed the relationship

between electrodermal lability and both psychological and

behavioral characteristics.

Lacey and Lacey (1958) showed

that electrodermal "labiles" (Ss above the median number of

nonspecific SRRs during rest) had faster reaction times and

made more errors than did the "stabile'' Ss.

Crider ( 19 7 2)

demonstrated that electrodermal labiles (as measured by

speed of habituation of SPRs to tones on tvTO different

occasions) showed superior performance in an auditory vigilance task. Further analysis based on signal detection principles led Crider to conclude that electrodermal labiles

do not differ from stabiles in any cognitive capacity but

do show differences in levels of motivation and arousal.

15

In an attempt to answer directly the question of

whether EDRs indicate emotion or attention, Flanagan (1967)

obtained measures of amplitude of SCR and ratings of emotional reactions and "attention-getting" value to photographic stimuli.

He found average correlations of -.64 between

magnitude of SCR and attention scale values and average

correlations of 0.32 between magnitude of SCR and emotion

scale values.

Since the correlations with attention were

significantly higher, Flanagan concluded that an attention

interpretation of SCR is preferable to one based upon

emotion.

D.

GSR And Learning

An early investigation of the relationship between GSR

and learning used a standard serial verbal learning procedure (Brown, 1937).

Larger SRRs were associated with the

learning process rather than with vocalization of the correct verbal response.

A subsequent study reported by

Kintsch (1965) employing a PA learning task demonstrated

that the amplitude of SRRs to a stimulus increases up to

the point of the last error, and then declines after learning has been completed.

The results obtained by Brown and

Kintsch might be interpreted as indicating that ORs are

evoked by the task demands placed upon the subject; when

the level of performance reaches that required by the

situation, the OR begins to habituate.

16

Germana (1968) pointed out that the above studies included no attempts ·to separate the activational responses

which occur to the different components of a learning trial,

since EDRs which occur to the stimulus member of a pair were

combined with the EDRs associated with the overt response

required of the S.

Therefore, Germana (1964) employed a

concept-formation task in which Ss were instructed to withhold their response to the stimulus until an interval of

time had elapsed.

Using that procedure, he reported that

the SCRs to the stimulus showed the characteristic increase

followed by a decrease in amplitude, whereas the SCRs concurrent with the overt responses did not show a similar

pattern.

Thus, the phenomenon which Germana describes as

"activational peaking" occurs as a result of Ss preparation

to respond, and the SCRs begin to diminish as learning

enables the S to respond with little preparatory effort.

An.dreassi and Whalen (1967) conducted two experiments to

investigate physiological activity associated with original

learning and overlearning of verbal materials.

The results

showed that there were increases in skin conductance with

new learning, decreases with overlearning, and further decreases with double overlearning.

It was concluded that

the drop in physiological activity which occurred with

overlearning was due to an habituation of physiological

response when Ss were no longer required to assimilate

novel materials and a reduction in apprehensiveness as

17

the experiment progressed.

A number of experiments utilizing EDRs have validated

the hypothesis that activation and performance follow an

inverted U relationship.

Berry (1962) presented Ss with a

PA learning task and measured SCL during the course of

learning and subsequent recall.

He reported that inter-

mediate levels of skin conductance during both the first

minute of the learning session as well as the first minute

of the recall period were associated.with better recall

performance.

Stennett (1957) compared the performance of

31 male _college students on an auditory tracking task under

different conditions of incentive.

Subjects performed

better in the "optimal arousal" condition than they did 1n

either the "low arousal" or "high arousal" condition.

Spencer studied activational

identification tasks.

pe~king

in two concept

The results support the hypothesis

that SCL is reflective of cognitive activity and that the

spontaneous SCR reflects the psychological stress accompanying the successful utilization of information intake.

Heasures of activation levels supported the inverted U

hypothesis (1972).

Simon reported negative findings on her investigation

of the relationship between the OR and both learning and

retention of verbal PA.

An attempt was made to induce

various levels of the OR by presenting PA lists containing

different numbers of stimulus words in a changed format.

18

Results indicated no reliable performance differences between high and low OR subjects.

The author suggests as a

possible explanation of the results that college students

are generally a highly select group, and are at an asymptotic level of attention (Simon 1970).

E.

GSR and the Learning Disabled Child

A search of the relevant literat~re found only three

studies of EDA in which the subjects could be considered to

be learning disabled.

One study was concerned with differences between

readers and non-readers with respect to physiological OR

patterns in the autonomic nervous system, particularly the

electroder·mal and cardiovascular responses to repeated

stimuli 1n series (Hunter 1972).

Autonomic response

patterns of twenty male non-readers ranging in age from 7

years 11 months to 11 years 4 months were compared with

those of twenty matched controls.

The authors found that

the non-reader's most noticeable characteristic was his

deficient or fluctuating attention which was reflected 1n

hi~

lower basal skin.conductance levels over trials.

Boydstun et al (1968) compared the patterns of skin

resistance and heart rate of 26 children ages 6-12 with

minimal brain dysfunction. with 26 control children during

an auditory discrimination task.

The authors postulated

that relatively simple and standard laboratory tests

19

would discriminate this clinical group from a group of controls.

They found that skin resistance gradients did sepa-

rate the two groups of children as controls had steeper

gradients than the clinical

group.

·,

The subjects who condi-

tioned well gave evidence of generalization in SR and heart

rate, whereas the subjects who conditioned poorly did not.

The authors suggested that defective arousal structures or

defective coupling of arousal structures and other perceptual and motor structures could explain the decreased autonomic reactivity, the longer reaction times, the short

attention span and poor concentration of some children with

learning disabilities.

Arousal structures in the brain

stem and limbic system are critical for attention and perception, and these same structures contain mechanisms 1mportant in autonomic and skeleto-motor functioning.

Dureman and Palshammar (1970) combined psychophysic~ogical

recording with a tracking task on seven children

9 to 10 years old rated by the'ir school teachers as Low

Persistence (LP) and seven rated as High Persistence (HP).

They hypothesized that the LP children are generally more

prone to anticipate failure and, therefore, .tend to resign

and give up earlier than the HP children.

Such a tendency,

if found 1n the tracking task, would be expected to be

accompanied by evidence of lowered activation and alertness

in the autonomic recordings.

Results indicated that the LP

children were significantly lower in initial skin conduc-

20

tance level than the HP children, and skin conductance

level than the HP children,_and skin conductance levels on

the LP children decreased further during the experiment.

Rugel (1971) evaluated the potential usefulness of EDA

as an indicator of anxiety in children with reading problems by investigating the relationship between arousal and

levels of reading difficulty in normal students.

were twenty second- and third-graders.

Subjects

The results of this

investigation supported the hypothesis that a child's level

of arousal increases as reading difficulty increases from

independent to instructional to frustration levels.

He

concludes that, "the fact that the GSR response was sensltive to changes in reading difficulty with these children

suggests that it is probably a useful diagnostic tool with

problem readers whose degree of frustration in the reading

situation is more intense."

Attention and the Learning Disabled Child

Attention deficits have long been associated with

children with learning disabilities.

Among the character-

istics of learn{ng disabled children are hyperactivity, distractibility, short attention span, impulsivity, perseveration, perceptual-motor deficits, memory deficits, poor

intersensory integration, and more specific deficits of

auditory and visual perception.

Researchers have sought to

determine if there is a single, more basic psychological

processing deficit which can account for these various be-

~···

~··

21

havioral symptoms.

Cruickshank and Paul (1971) point out

that the field of learning disabilities sprang from earlier

work with brain damaged children.

They state that the char-

acteristics of learning disabled children mentioned above

are due to the "child's distractibility, that is, his inability to filter out extraneous stimuli and focus selectively on a task"(p. 37-3).

In addition, Dukman and his

colleagues (1971) have developed a theory which postulates

that organically based deficits in attention explain the

core group of symptoms associated with the learning disabilities syndrome.

Ross, in his book Learning Disability:

The Unrealized Potential (1966) defines a.learning disabled child as:

"a child of at least average intelligence whose academic performance is impaired by a developmental lag

in the ability to sustain selective attention.

Such

a child requires specialized instruction in order to

permit the use of his or her full intellectual potential." (p. 11).

Tarver and Hallahan (1974) reviewed twenty-one experimental studies of attention deficits in children with

learning disabilities.

The following conclusions were

drawn from their research.

"1) Children with learning disabilities exhibit more

distractibility than controls on tasks involving embedded contexts and on tests of incidental vs. central

learning; 2) Hyperactivity of children with learning

disabilities may be situational-specific, with higher

levels of activity being exhibited in the structured

situation; 3) Children with learning disabilities

are more impulsive, i .. e., less reflective, than controls; 4) Children with learning disabilities are

deficient in their ability to maintain attention over

prolonged periods of time." (p. 36)

-----~=---

~----

~·-

CHAPTER III

Methodology

Pilot Study

In early 1978 following a rev1ew of literature dealing

with attention, learning, and activation, I had discussions

with several authors who are prominent in the field of

Biofeedback including Barbara B. Brown, Ph.D.,.author of

New Mind, New Body (1974) and Stress and The Art of Biofeedback (1977), George D. Fuller, Ph.D., Associate Clinical

Professor in the Department of Biological Dysfunction, U.C.

Medical Center, San Francisco, author of Biofeedback Methods

and Procedures in Clinical Practice (1977), David French,

Ph.D., President of the Biofeedback Society of· California,

and Melvyn Werbach, M.D., Director of Clinical Biofeedback,

Pain Control Unit UCLA Hospital and Clinics.

These discus-

sions convinced me that the GSR may be a useful way of looking at the process of learning 1n the learning disabled. I

first explored the methodology 1n a pilot study in July of

1978.

Subjects consisted of seven children ages seven to

thirteen who were then seeing me for Educational Therapy at

Ross Loos Medical Group in Encino, California. These children were all referred for remediation of learning problems.

??

23

They were of at least average intelligence as measured by a

WISC-R.

Achievement scores on the Wide Range Achievement

Test placed them two to three years behind grade level in

reading, math and spelling.

'

A Toomin GSR instrument, model 505, was used.

Measure-

ments were taken from the palm of the dominant hand.

The

initial measurement was taken following attachment of the

electrodes.

A second measurement was made after the

subject was instructed to take a deep breath and exhale

slowly.

The final measurement was taken following a loud

noise made to startle the child.

Results were consistent with the inverted U hypothesis.

Five of the Subjects displayed skin conductance (SC) levels

1n a similar range.

One Subject had very low readings which

barely moved with either deep breathing or a startle.

Subject was felt to be clinically depressed.

This

The seventh

Subject had values much higher than all the others.

This

Subject was very anx1ous and seemed to be holding in feelings of anger.

Since it appeared that children with either unusually

low or high arousal, in contract to the chil.dren with moderate levels of SC, were experiencing emotions which could

interfere with learning, it occured to me that

sc

levels

might differentiate between high and low performance on a

learning task.

In other words, subjects with very high or

very low levels of SC may perform less well due to inter-

ference with the process of learning.

Following the pilot study, I began the following

research study of the SC patterns of learning disabled

children.

Statistical Design

The statistical design used was a 2x2 Factorial Design

(Sheridan 1971).

In this design two or more variables

(performance and activation) are manipulated simultaneously,

showing modifications in functional relationship for a given

independent variable as a function of changes in the other

independent

variable~

Null Hypothesis:

Activation as measured by skin conductance

levels is not related to performance on a Paired-Associates

task for learning disabled children.

Dependent Variables: Changes in skin conductance levels

during performance and number correct on the test.

Independent Variable:

The Paired-Associates task.

Subjects

Subjects consisted of a total of

forty~four

children

referred to the Department of Mental Health of Ross Loos

Hedical Group for the evaluation and/or treatment of learning problems.

Ross Loos is a large, private prepaid medical

care plan operating in the greater Los Angeles

area~

Members

range in socioeconomic class from the upper end of the lower

25

class to the upper end of the middle class, each family

having at least one person who is employed.

Subjects were

seen at the Ross Laos offices in Encino, Santa Ana, Torrance

and downtown Los Angeles, California~

The subjects ranged in age from five years to fifteen

years.

They were of at least average intelligence as meas-

ured by a \..JISC-R or Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test.

Achievement scores on the Wide Range Achievement Test or

the Peabody Individual Achievement Test placed them one to

five years behind grade level in reading,

~ath

and spelling.

Procedures

Subjects were introduced to me by their Educational

Therapist who stated that I was to do a learning test with

them.

The therapist stayed in the room during the experi-

ment.

The subjects were seated opposite me at a desk.

Subjects were first given a brief introduction of the

task which included information about how the measurements

would be taken.

questions.

They were given an opportunity to ask

When they indicated they were ready to begin,

the palm of the dominant hand was wiped clean, and silver/

silver chloride electrodes were filled with electrolyte

and attached with a Velcro band ..

Readings were taken at five points during the experlment.

The first reading was taken thirty seconds after the

subject was instructed to sit back and relax.

The subject

was then instructed to take a deep breath and exhale slowly

,,_

26

and the second reading recorded the maximum SC immediately

following the deep breath.

The third reading was taken

immediately after presentation of the final Paired-Associates item; the fourth was taken immediately after presentation of the first test item.

The final reading was taken

immediately after presentation of the last test item.

Instrumentation

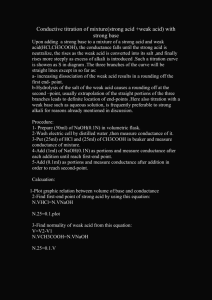

Ten pairs of geometric designs were designed by me for

this experiment.

(Figures land 2, pp. 27, 28).

drawn on 3"x5" white cards with black ink.

They were

I decided to use

simple geometric designs rather than meaningful words in

the Paired-Associates task because of the following:

the

subjects in the study included ages five through fifteen

with different degrees of academic achievement; learning

disabled children often have difficulty with reading words

(Myers and Hammill, 1976).

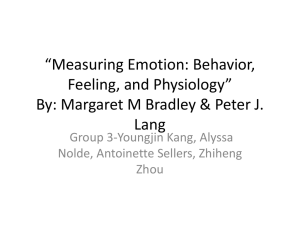

Measurements were taken on a Toomin GSR instrument,

model 505.

(Figures 3 and 4, pp. 29, 30).

has six selectable scalei:

The Toomin 505

0-10, 10-2G, 20-30, 40-50, and

0-50 micromhos for recording skin conductance levels.

The

students received no audio or visual feedback during the

testing.

I monitored only the visual feedback on the

machine.

Batteries were checked daily.

27

Flrur·~

1

·-Task

•

Car~s

•

•

·•

•

•

•

~

I

I

j _ _ __ _ _ _ , /

28

F1yurt'! 2

Task Carrls

X

29

.. -

_._;.':-.:·

~~-~: ---~ ....--~-~

~--'

-.:••-."7:".-.-.;:_

--:---:-~~·-'"::--

~-=::£::Z...:..::..::.~:

.

.

<

·' ..

::~

•

·:0;

.

Since 1972, the Toomim 505 GSA has been in daily use

in our Psychotherapy Center, and has been developed

and refined principally lor use by psychotheraoists.

Since its clinical introduction, and the pioneering clinical research here by Majorie Toomim, Ph.D., Director

of Psychological Services, the Toomim 505 GSR has

become the most widely used professional GSR in

the U.S.

The T oomim 505 measures changes in skin conductance-on the palmar surfaces in micromhos, providing

rapid, sensitive audio and visual fpedback on Sympathetic Ner>~ous System activity. Palmar electrodes produce less movement artifact than linger electrodes,

and the T oomim silver-silver chloride electrodes preclude interfering interface potentials and insure accurate, repeatable measurement.

Dr. Toomim has found that GSR feedback represMts

a guide lo both there.oist and client as to u-~e value of

the content in a ther-a.pcuiic transa.:::tion. The therapist

is less likely to be led into blind alleys and trapped by

defensive maneuvers. Most clit:nts appreciate this objective ~vidence of re!cvance. It cuts down tneir time in

therapy and deepens the level at which they work. The

client's resistance to threatening material is reduced,

thus smoothing the flow of the therapeutic expenence

fur both therapist anJ clier.t.

GSA biofeedback is a useful aid in dynamic psychothera;>y and behavior modificatiOn approaches. I! mcree>ses the efJP.~tiver1ess of lhc theraoist throuah providtng immediate awareness of bodv-minc re;ationshiPS and S•;mpa:he!ic Nervous Sy!:>te.m reactiVIty pat.

terns. It furlrw: prov1oes the cltenl W!lh a full awareness

of himself. encourages the cooperation of the client,

and r£>duces the hit or m1ss quality of \he therapeutic

-

;,c..~

:_.c._{. ci.' ., ..

. . . ,. ..

-~~--

-.u.:...-:.--'--~_.;,:

.... ._.·.:._,'-•-e.:.•..._......_,...,_.

-~-- ...;.0.....

process. It adds a naw dimension to the pr.3.ctlce o'

psychother~py the- direc! training ct aysfun-:t1ona·

Sympathetic Nervous System reactivity patterns an::

some of the attitudes that maintain the stress response.

The introduction of continuous monitoring of 1nterr.a!

processes within the lherapeutic setting reducc!i thebody-mind dichotomy.lt is pa,..ticularlv valuable to the

primarily verbal therapist who wants d~rect access to

the body.

The Toomim 505 has six selectable scales: Q-10, 10--2C.

20-30. 30..40, 4()..50 and 0..50 m•cromhos. For the occaSIOnal subject who requires greater sensitnrity, any 2

micromho interval on any of the micromho scales ca.be selected and expallded over felt scate with the Sca}e

Expansion Switch. Changes of 0.02 micromhos are

then apparent.

The fu!l range 0-50 scale is specifically destgned tor thf

psychotherapist. Wi1h the Expanded Scate on, ampt ...

tied mte of change information is aoded to the stablfread:ng so that 2 mic.-rc-mhos per second rate of chan~

c2uses full scale meter deflection and large ton~

change that calls aneiltion to small resoonses. Tt·oo!

needle and tone qwckly return to the newiy estabiishee

value en the 0-50 s-cale. In this mode. the 505, anoras

full "HANDS OFF" operat1on with maximum sensitlvi:)·Precision averaged GSR readinps, percent time rea.:JJnps. and thres:-Jold measurements from 10 to 18):

seconds may be obta;;""lr:d by using the Toomim 505 I!"•

conJunction wnh th-e- Toornim 507 Dtgital lntFgraLor

Tr1is orov1des a research Qual tty system and a leccoa:s

sconng systemy in addition to session to scsSIOI"'

records.

BIOFEEDBACK RE.S~ARCH INSTITUTE, Inc. 6325 Wil~hire Boulevard. Los Angetss~ California r«1413 (213) 933-9451

30

MODEL 505 - TOOK!I4 PROFESSIONAL GSR/E!P SPECIFICATIONS

GSR Electrode Polarizing Potential:

EDP Input Resistance: 10 megohm.

0.170 volts.

FEEDBACK

Variable pitch flute-like tone 50 to 1000Hz.

Internal loud speaker with controllable volume.

3 1/2" linear conductance meter.

SCALES

0-10; 10-20; 20-30; 30-40; 40-50 micromho, overlap 2 micromho.

Above scales are expnndable, any 2 micromho Interval to full scale.

0-50 mlcromho with 10 rnicror.-.ho extension.

Expansion cwitch cdr.s rate of chanoe indication to 0-50 scale.

Full ~cale dof lection with 2 ;;.;cromho per second, and comparable

tone variation.

CONTROI_S

Vol ume/Po.1er on-off.

Function: GSR, Battery, EDP.

Scale Selector, 6 scales.

Scala Expansk,~/~leter position.

Polarity + or - for EO? function only.

PANEL

COtU~ECTORS

Electrode Input; 4 pin Din.

External '"eter; 1/4" stereo phone jack 0-1 rna, and for Digital Integrator.

Phones; 1/4" stereo phone jack, 8-16 ohm.

PHYSICAL

Operatlr.g ranoe: 50 to 110• F.

PowP.r: 2-'J v;lt ~INI604 Mallory alkaline transistor batteries.

Battery life: 25 hr. continuous 30 days typical clinical use.

Size: 4 5/~" high, 3" deep, 10" wide.

~Ieight:

2.5 lbs •

.STANDARD ACCESSORIES

One 5' 5et of 3 sl lver-si lv~r chloride electrodes, Velcro backed.

15" Velcro band for holdino electroe<>s on hand.

~" electrorJr, placement bar: Velcro s;.:rfaces.

I 1/4 oz. electrode cream.

31

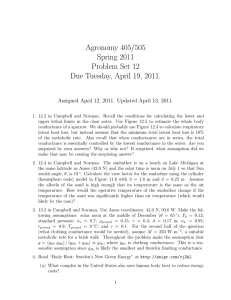

Data Collection and Recording

For the purposes of data collection and recording a

one page sheet was designed.

On it the subject's name,_ ..

date, dominant hand, therapist's name, and the five readings

were recorded.

This page also included all verbal instruc-

tions to insure that the same instructions were given to

each subject. (Figure 5, p.

32).

Data was transferred from the individual data collection sheets to one page which had the following column

headings:

Name, Age, Preferred Hand, Baseline, After Deep

Breath, After Presentation of PA Task, After Test Item #1,

After Last Test Item, Number Correct On Test.

p.

33 ).

(Figure 6,

Of the data collected only Number Correct On Test

and the level of SC as recorded immediately after presentation of PA Task were selected for analysis.

32

,-~-~-··----~

..

- .-

--

';····~-

"?I,!.'?.E 5

.OubJec':;

Date: _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __

1ntro:

~!y nan~ ts Gall '..J~rtach :~r.i'. I al'l an Zclucatlon:'ll 'rher:1pist at

!l-L and I work with

• I an here t;o do a

8l.L"Itle lean:i!"l~ t::tsk with you. i. am ~olng to te givlr..~ you a

series of r-~irs c~ cn~d5 to 1~~~. A~ the sa8e time I am

goin~ to ~ ta~ln~ ~e~surB~e~ts from a ~achi~e.

Thl3 ~3c~tr.e

won 1 t do .!lnyf:hinz "!:a y·Ju~ ::1ll it dces L-1 .:sl•te us me::1sure~ents

which h~l? us unr..et"st·o1wl how 'fC'l lea!'!1. After cur c.ee':tn~ I will

r~view r.ry f!.n'lin~s .,.,it:h .:rc11r therapist who woul:j_ ::e ha~p:r to dlSC!.lSS

them further with y0u or your ~~nts if you wish. Ar~ questions?

?rep:

~ow

I am goinp; to te hocki!'ll," you up. This Machin~ dcesn 1 t do anythinv, to you, 1 t Just me.asures responses. ~ihich ha:J.d do you ;n•i te

with?

This cream just helps ;.rith the measurer.~ents.

Sit back, nake yours~lf cor.~fortable while I take my first reading.

It is ir.mortant to ~eep stl.ll as !!lover.~P.nts affect the readl.n~.

',.'ait )0

sec.

?irst reading:

Nm1 take as deep

Second

readin~:

Peak

a breath as you can and let i t out.

readin~

durir~

deep breath: _____________________

I am now ~oin~ to show you ten pairs or oar1s. Sach of the cards

belona:s with the oth"r in its ~air. ;1emorize each pair. Later I

sho·.• yo•.1 one picture f!"Or! e;:.ch pair and ask you to select the

other picture which o;o-:i.s · >~Uh it.

Do you un1c~sta~1 thf~ instructions: ~/ertal s3.!!1plo&;s !;1 ven.

·,o~ill

Ar~

~ask:

JOtl

r~l'l-iy?

Present each ;;-air for 10 seconds each.

chird reading:

~ow I am ~oi~g to ask you to ~atch the carrl I hold uo with the

number of the ce.r~ which is its oair. 'dhen I hold up a caM, don't

point just say the nu::~~er of the· correct pair. If you -:l.on't know-guess

Are yo'J. re-9.rly'?

S~~ow

Ans•,o~er

Shml

_ ~· A~s1-1er

:est:

.

·-

~~~-1~----~~'-----~------J..

-:l·

Lt

~

---

0

L\.

?'1fth readin»:

I

s

/0

R

c7_

9

l_

/-----;/

0

3

1

(:,

NAME

AGE

PREFERRED

HAND

.

.I

'

BASELINE

AFTER DEEP

BREATH

:

...

..

.

. .

I

·i

I

..

.

.

. .

.

..

.

.

. ..

AFTER

PRESENTATION

OF PA TASK

AFTER TEST

ITEM #l

AFTER LAST

TEST ITEM

NUMBER CORRECT

ON TEST

w

(.&.)

34

. Da·ta Processing and Analysis

A total of forty-four subjects were tested as described

in Chapter 3.

After testing twenty-nine subjects a prelimi-

nary data analysis was performed.

A list was made of the

subjects' age and number of correct responses. (Table 1,

p. 35). On the basis of the preliminary data it was decided

that the Paired-associates task (PA) resulted in a fairly

even distribution of correct responses of subjects between

ages five and thirteen.

The task, however, appeared too

simple for children aged fourteen and above since four out

of seven of the latter received ten out of ten correct and

non~ ~f

the children ages five to thirteen received that

score.

Thus a decision was made to modify the original

design of the study by limiting the maximum age of subjects

to age thirteen.

Data on the seven older subjects were

excluded from further analysis.

Levels of skin conductance of the thirty-seven subjects

as measured immediately following presentation of the last

of the PA cards were selected for statistical analysis.

Log skin conductance ranged from 0 to 1. 8 micromhos, with a

mean of 0.86 micromhos and Standard Deviation of 0.44 micromhos.

Number of correct responses varied from 0 to 9, with

a mean of 5.08 and Standard Deviation of 2.29.

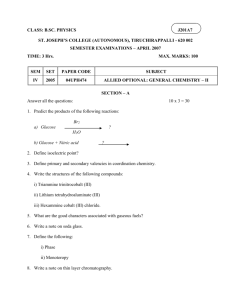

Table 2,

(p. 36) • . Subjects who displayed a moderate level of skin

conductance ranging from 0.6 to 1.1 log micromhos were compared with subjects ~ith levels of skin conductance beiow

35

TABLE 1

Preliminary Data:

Name

Ranked By Age

Age

L.W.

B.B.

R.C.

D.P.

K.H.

F.C.

A.

15

15

14

14

14

14

14

M.B.

J.R.

D.R.

13

12

12

11

11

11

10

10

10

10

c.w.

L.U.

R.H.

P.F.

s.s.

M.S.

D. F..

D.D.

K.T.

D.D.

C.K.

M.

M.M.

T.Q.

B. G.

K.G.

9

9

9

Number Correct

10

8

10

10

10

7

5

3

5

4

6

5

5

8

8

7

6

5

5

0

4

1

B.

8

8

8

8

8

8

8

6

P.

5

3

J.

9

6

6

7

5

6

36

TABLE 2

Final Data:

Name

Ranked by Log Skin Conductance

Log Skin Conductance

Number Correct

·,

T. Q •.

c.w.

T.T.

J.

D.D.

J.

J.

D.R.

s.s.

P.

A.

E.

K.G.

C.K.

P.F.

K.T.

D.D.

T.M.

T.

L.U.

D.R.

J.R.

M.B.

D.

M.

M.

R.H.

M.S.

M.

D.D.

B.

G.C.

D.H.

M.M.

M.

B.G.

w.

0

0

0

0.3

0.3

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.6

0.7

0.7

0.7

0.7

0.8

0.8

0.8

0.8

0.9

0.9

1.0

1.0

1.0

1.0

1.1

1.1

1.1

1.1

1.2

1.2

1.3

1.4

1.4

1.4

1.4

l. 6

1.8

4

6

6

5

5

3

2

4

8

3

7

7

7

9

8

5

5

5

6

5

6

5

3

7

8

3

5

7

8

0

6

0

6

6

6

l

l

37

or above those limits.

The sample was also subdivided

according to the number of correct responses.

One group

achieved 0-4 correct responses; the other group achieved

five or more correct responses.

A Chi Square analysis was done by compar1ng the observed frequencies in each of the resultant 4 cells against

the expected frequencies.(Table 3, p. 38).

found to equal 4.69.

Chi Square was

For one degree of freedom these

results are significant at the .G5 level.

The null hypo-

thesis was rejected; performance on the paired-associates

task for. learning disabled children was found to be related

to activation as measured by skin conductance levels.

Methodological Assumptions

For the purposes of the study the following methodological assumptions are made.

Measures of SC are valid.

Measures of SC are reliable.

The performance of learning

disabled children on the PA task will be evenly distributed

over a bell shaped curve.

Levels of log SC will follow a

bell shaped curve.

Limitations

Possible limitations of the study include (1) the

sample comprised a specific population which may limit the

generalizability of the findings to other populations,

(2) skin conductance levels do not necessarily correlate

with other activation measure, (3) a paired-associates

task need not correlate with academic performance, (4) the

38

'TABLE

3

Observed Versus Expected Frequencies

Log Skin Conductance Levels

Moderate

Cl)

0-'+

Q)

Cl)

Expected Frequency

14

Expected Frequency

12

Observed Frequency

Observed Frequency

17

~

Extreme

ITotal

26

9

0

p.

Cl)

Q)

Expected Frequency

p::;

6

-j-l

0

Q)?

HH

0

(.)

5

Observed Frequency

3

Expected Frequency

5

Observed Frequency

8

11

39

wide range in age and degree of learning disability between

subjects may have masked findings which would have emerged

had the study been limited to a more narrow age range, (5)

artifact in GSR measurement technique may have distorted

the data.

CHAPTER IV

Analysis and Evaluation

Findings

In finding the research hypothesis tenable, that is,

performance on the paired-associates (PA) task for learning

disabled children was related to activation of electrodermaL activity as measured by skin conductance levels, the

results confirm and extend those reported by Berry (1962)

in his study relating skin conductance to performance on a

PA task for college students.

Since an exhaustive review

of the literature failed to reveal any other studies

investigating the relationship between skin conductance

and performance in a learning task (see Chapter 2), a

detailed analysis of the comparisons between the present

study and Berry's study is pertinent.

Highlights of these

comparisons between the two studies are summarized in

Table 4 (p. 41).

40

Table 4

BSRRY

<~ERBACH

SXP. 1

SXP. 2

18 Males

SAl!.;' IE

(Paid)

Colle~~;e

25 Males and 12 Females

32 Males

{Unnairl.)

(Ur.paid)

Children with Learning Problems

Students

;

Not stated

JO

LEAP.NING

Pairs Of

Meanin~ful

Ae;es: 5-13

r-:--

Words

Pairs Of Geometric Designs

I

TASK

I

··-·

------~·-·-~~--· -~-------r--·----------·

ELECT::! ODE

PLACEMEJ:.IT

I

I

'

--~----l---·

SK!~

PR::7PA!U'l'!C!1

II

Left Palm

_liE_"'_S_:""_:.._T_S_ _ _

Alcohol Rub Before Slectrorl.e

Placement

I-

,,;ribod

Palm Wi?Sd Clean

I

D"":~~~on,-, ::-~:cut, ~--~::~:-~~~~:~:~:~e~~~o:~~- 50;··--· .

A•

in

Ap:paratus for recordin.(!' 11utonom1o states

a~d chanll;es. Amer.J. Psychol., 1954,6?,

343-352.

I

r

-i--M~~-:-;:~:·-:~~~~- of--~~~ -o~~~uc:~nce -:~--:he- --~~ode rate

.

ANAL!SIS

.....

I

end of the first minute of the "learnin~~;

session were related to better recall.

STAT:STICAL

-··------~

Ir·. -· Palm of Dominant Hand

.

SQ.UI?'SNT

.

. . . --·-··· -····· ___ _.,_, --- ,___ ·-·-· -·

I

Fisher's exact test

····-··

i

c·o:~=t~~~-~

levels of skinat the

end of presentation of learning task were

related to better recall,

·,--.

\

··-·-----------·------ ... ·----···- ....

Chi Square

I

I

42

Discussion

Berry conducted two experiments.

There were eighteen

subjects in Experiment 1 and thirty-two subjects in Experiment 2.

Subjects were

m~le

college student volunteers.

Subjects were paid in Experiment 1, but not in Experiment 2.

The current study analyzed the data from thirty-seven subjects, twenty-five males and twelve females between the

ages of five and thirteen years. These students participated

in the experiment during their regular educational therapy

session.

In the Berry study, the data were continuously recorded

in a recording room separated from the experimental room by

a sound-reducing partition.

There was an experimenter 1n

the room with the subject and another in the recording room ..

In the current study, the data were recorded at fixed points

by the experimenter in the room with the subject.

In Berry's study, palmar skin conductance was recorded

from an electrode placed on the left palm, after the area

was rubbed with alcohol.

In the current study, electrode

placement was on the palm of the dominant hand (the one the

subject used for writing

which was first wiped with a

tissue.

In both experiments, the task consisted of the presentation of paired-associates to be memorized and recalled.

Berry used 30 paired items (meaningful words) from a list

by Melton and Safier, published by Hilgard (1951).

The

43

current study used ten paired items (geometric designs)

which I designed.

In both experiments the pairs were shown

on 3 "x5" car·ds which had been shuffled before the experiment

was begun; each subject was presented with this same order.

Berry's subjects were presented with sample cards; in the

current study the sample was presented verbally.

In both

cases the subject was told that he or she would be required

to recall the right-hand (response) item of each of the

pairs when presented with the left-hand (stimulus) item.

The latter was presented on another set of 3"x5" cards

which also had been shuffled previous to the experiment.

In the Berry study the subject received ten seconds

to study each pair and a ten second intercard interval.

There was a six minute interval between the learning and

the recall session, and ten seconds to respond to each card

in the recall period.

a

All cards were presented manually on

small table in front of the subject.

In the current study

the subject had ten seconds to study each pair and a five

second intercard interval. There was a three minute interval

between the learning and the recall session and ten seconds

to respond to each card in the recall period.

All cards

were presented in the same manner.

Berry plotted the log conductance level of the first

minute of the ten minute learning session against recall

score.

In the current study, the log conductance level

immediately following presentation of the paired-associates

44

cards was plotted against recall score.

Berry used Fisher's

exact test for data analysis; by contract this study used a

Chi Square analysis which is a more powerful statistical

measure.

Interpretation

Because of these differences in methodology, this study

cannot be considered an exact replication of the Berry

study.

However, since results of this study replicate

Berry's results, it would appear that skin conductance

levels may relate to performance for learning disabled

children in the same manner as for adults without learning

problems.

Taken together, the results of the two studies

would suggest that optimal performance on a learning task

is related to moderate levels of activation regardless of

age or academic achievement.

In interpreting the data from the current study, I might

suggest that children who demonstrated low levels of skin

conductance were not actively engaged in the task.

This is

consistent with studies done by Hunter et al (1972),Dureman

(1970), and Boydstun (1969).

Hunter compared autonomic

response patterns of twenty male non-readers ranging in age

from seven years to eleven years with those of twenty

matched contr•ols.

Results showed that non-readers had

lower mean skin conductance levels across trials.

The

authors interpreted the data to suggest that non-readers

were physiologically less mature and unable to maintain a

45

constant attention level, their most noticeable characteristic being deficient or fluctuating attention.

When the

disabled reader was specifically instructed to attend to a

simple reaction time task, he and his control had approximately equal skin conductance levels.

However, mean skin

Conductance level-for disabled readers dropped off rapidly

over the four subsequent trials while controls appeared to

remain alert, with little decrease in basal level.

The

authors commented that the reading disabled child seemed

unable to "stay with it".

Dure~an

and Palsarnrnar found that children who were

rated low in 'persistence' also bad significantly lower

skin conductance levels than their matched controls.

Boyd-

stun et al found that, although children with learning

disabilities did not differ from their matched controls 1n

resting physiological levels, they were less reactive physiologically to "meaningful" stimuli.

It can be further inferred that children 1n the present

study demonstrating high levels of skin conductance were

overly anxious.

High levels of anxie·ty may have inhibited

performance by shortening attention span..

tent with results reported by Rugel (1971).

This is consisHe evaluated

the potential usefulness of the SSR responses as an indicator of anxiety in children with reading problems. . He found

that the level of a:rousal increased as the level of reading

difficulty increased.

Children used in his study were

46

average, not retarded, readers.

Rugel reviews studies by

Phillips (1967) and Sarason (1966) who have found that

anxiety is negatively related to reading achievement in the

elementary school grades.

Summary of Chapter

In finding performance on the paired-associates task

to be related to activation as measured by skin conductance,.

levels the results supported the Researcb Hypothesis and

extended the results reported by Berry in his study relating

skin conductance to performance on a PA task for college

students.

A detailed analysis of the comparisons between

the present study and Berry's was presented.

It was suggested that learning disabled children with

low levels of skin conductance were not actively engaged in

the task.

studies.

This finding was consistent with several reported

Furthermore, children in the present study demon-

strating high levels of skin conductance were seen to be

overly anxious.

g1ven.

Evidence supporting this finding was also

'*''·

CHAPTER V

Summary, Conclusions, Recommendations

Summary

In recent years, educators have shown increasing concern over the problems of learning disabled children.

This

study explores the relationship between activation and

learning among the learning disabled by·utilizing electrodermal patterns of response as the measure of activation

and a paired-associates task as the measure of learning.

A review of the relevant literature concerned with

activation theory and electrodermal activity is presented.

Studies involving the learning disabled child and measures

of activation and attention are revi.ewed.

The Research Hypothesis was: Is performance on a pairedassociates task for learning disabled children related to

activation of electrodermal activity as measured by skin

conductance levels?

Forty-four children were tested and

levels of skin conductance immediately following presentation of the learning task were selected for statistical

analysis.

level.

Chi Square analysis was significant at the .05

Subjects with a moderate level. of skin conductance

(0.6-1.1 log micromhos) were more likely to perform better

than subjects v.Jith either lower

conductance.

47

or higher levels of skin

48

Conclusions

This study has identified a subgroup of the learning

disabled population whose performance may well be hampered

by abnormally high or low levels of skin conductance.

However, the findings do not substantiate the existence of

the inverted U hypothesis, even though they are consistent

with such a model.

Recommendations

It is recommended, therefore, that learning disabled

children be trained to achieve moderate levels of skin

conductance with trainirig procedures designed to alter

their level of activation.

Such methods might include the

direct feedback of information derived from skin conductance

readings as well as other techniques such as meditation,

breathing techniques, autogenic training,, hypnosis, and

progressive muscle· relaxation.

A further recommendation would be to replicate this

study using a larger sample in order to provide additional

data to support the inverted U hypothesis.

REFERENCES

Andreassi, J. & Whalen P.

Some physiological correlates of

learning and overlearning. Psychophysiology, 1967, l'

406-413.

Belloni, M. L. The relationship of the orienting reaction

and manifest anxiety to paired-associate learning.

Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of

California, Los Angeles, 1964.

Berry, R.N.

Skin conductance levels and verbal recall.

Journal of Experimental Psychology, 1962, ~' 275-277.

Boydstun, et al.

Physiological and motor conditioning and

generalization in children with minimal brain dysfunction.

Conditional Reflex, 1968, Apr.-June, 81-104.

Brown, B.B.

Stress and the art of biofeedback.

Harper and Row, 1977.

Brown, B.B.

1974.

New mind, new body.

New York:

New York: Harper and Row,

Brown. C. H. The relation of magnitude of galvanic skin

responses and resistance levels to the rate of learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 1937, ~'

262-278.

Clements, S.D.

Minimal brain dysfunction in children.

Washington, D.C.: Co-sponsored by the Easter Seal

Research Foundation of the National Society for

Crippled Children and Adults and the National Institute

of Neurological Diseases and Blindness, Public Health

Service, 1966.

Crider, A.

Electrodermal lability and vigilance performance.

Psychophysiology, 1972, ~' 268.

(Abstract).

Cruickshank, W. M. & Paul, J. L. The psychological charac_te~istics of brain-injured children.

In W.M. Cruickshank (Ed.) Psychology of Exceptional Children and

Yout~.

Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1971.

Davis, R.C. et al.

Autonomic and muscular responses and

their relation to simple stimuli.

Psychological Monographs, 1955, 69, 1-71.

49

50

Duffy, E.

Activation and

behavior~

New York: Wiley, 1962.

Duffy, E. & Lacey 0. L. Ada.ptation in energy mobilization:

Changes in general level of palmar skin conductance.

Journal of Experimental Psychology, 1946, ~' 437-452.

Dureman, I. & Palshammar, A.

Differences in tracking skill

and psychophysiological activation dynamics in children

high or low in persistence in schoolwork.

Psychophysiology, 1970, I, 95-102.

Dykman, R.A. et al.

Specific learning disabilities: An

attentional deficit syndrome. In H.R. Myklebust (Ed.)

Progress in learning disabilities, Vol. 2, New York:

Grune & St~atton, 1971.

Edelberg, R.

Electrodermal recovery rate, goal orientation,

and aversion.

Psychophysiology, 1972, ~' 512-520.

English, H. & English, A. A comprehensive dictionary of

psychological and psychoanalytic terms.

New York:

McKay, 1958.

Fere, C.

Nte sur les modifications de la resistance electrique sous l'influence des excitations sensorielles

et des emotions.

Comptes Rendus Societe de Biologie,

1888, (Ser. 9), ~' 217-219

Flanagan, J.

Galvanic skin response: Emotion of attention.

Proceedings of the American Psychological Association,

1967, l' 7-8.

Fuller, G. D.

Biofeedback methods and procedures in clinical practice.

San Franc1sco: Hiofeedback Press, 1977.

Germana, J. Autonomic correlates of acquisition and ex·tinc,....

tion. Unpublished master's thesis, Rutgers University,

1964.

Germana, J.

Psychophysiological correlates of conditioned

response formation.

Psychological Bulletin, 1968, 70

105-114.

Hebb, D. 0.

system).

Drives and the c.ri~s. (conceptual nervous

Psychological Review, 1955, .§1_, 243-254.

Hilgard, E. R.

Methods and procedures in the study of

learning.

In S.S. Stevens (Ed.) Handbook of experimental psychology.

New York: Wiley, 1951. Ch. 15.

51

Hunter, E., Johnson, L. & Keefe, f.

Electrodermal and

cardiovascular responses in nonreaders. Journal of

Learning Disabilities, 1972, ~, 14-24.

Johnson, H. & Campus, J.

The effect of cognitive tasks and

verbalization instructions on heart rate and skin

conductance.

Psychophysiology, 1967, ~' 143-150.

Kaplan, S., Kaplan, R., & Sampson, J. Encoding and arousal

factors in free recall of verbal and visual material.

Psychonomic Science, 1968, 12, 73-74.

Kintsch, W.

Habituation of the orienting reflex during

paired-associate learning before and after learning has

taken place~

Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 1965,

~' 330-341.

Lacey, J.I. & Lacey, B.C. The relationship of resting

autonomic activity to motor impulsivity.

In The brain

and human behavior, (Proceedings of the Assn. for

Research in Nervous and Mental Disease), Baltimore,

Md.: Williams & Wilkins, 1948, pp. 144-209.

Liederman, P.H. & Shapiro, D.

Studies on the galvanic skin

potential level:

Some behavioral correlates.

Journal

?f Psychosomatic Research, 1964, I, 277-281:

Lindsley, D.B.

In S.S. Stevens (Ed.), Handbook of Experimental psychology.

New York: Wiley, 1951. pp. 473-516.

Lindsley, D. B. Attention, consciousness, sleep and wakefulness.

In J. Field, H. W. Maigoun, & E.v. Hall (Eds.)

Handbook of physiology, Section l, Vol. 111. Washington,