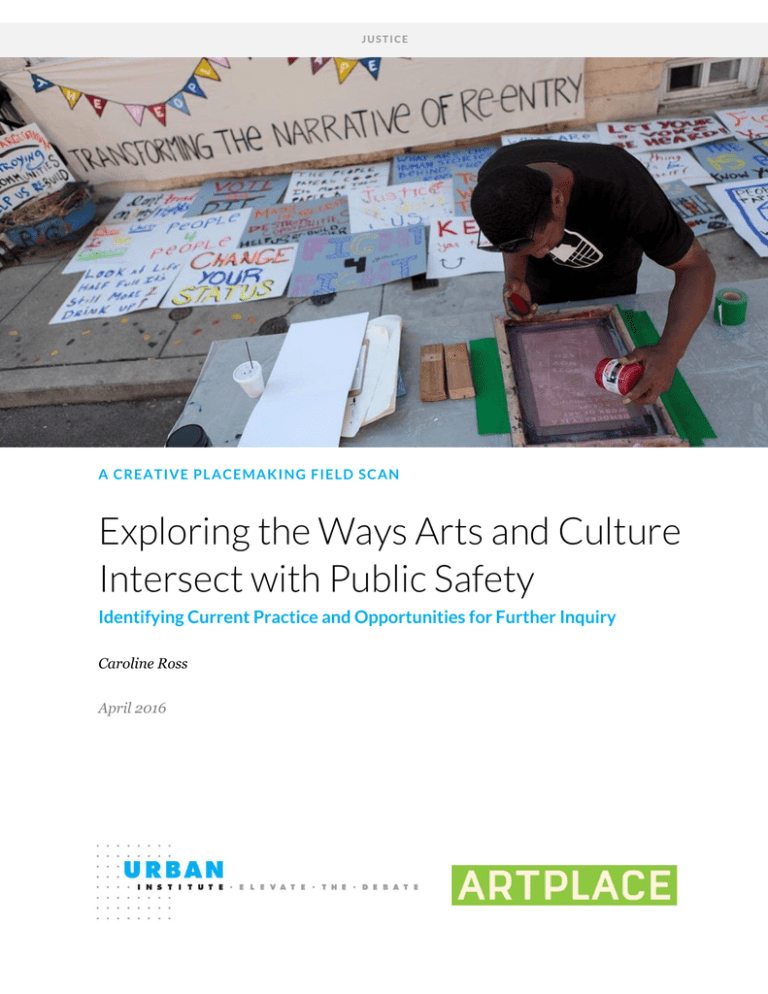

Exploring the Ways Arts and Culture Intersect with Public Safety

advertisement