Current Research Journal of Social Sciences 1(3): 93-110, 2009 ISSN: 2041-3246

advertisement

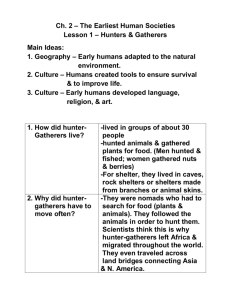

Current Research Journal of Social Sciences 1(3): 93-110, 2009 ISSN: 2041-3246 © M axwell Scientific Organization, 2009 Submitted Date: September 02, 2009 Accepted Date: September 14, 2009 Published Date: October 30, 2009 Corporate Social Responsibility: A Case Study on Quality of Life of People Around Bargarh Cement Works of Orissa (India) 1 P.C.Mishra, 2 Braja Kishori Mishra , 3 P.K.Tripathy, 4 Kumarmani Meher and 5 M.K.Pradhan 1 P.G. Departm ent of Environmental Sciences, Sam balpur University, Jyoti Vihar -768 019, Orissa, India 2 Departm ent of Home Science, Sam balpur University, Jy oti Vihar -768 019, O rissa, India 3 Departm ent of Eco nom ics, Sambalpur University , Jyoti Vihar -768 019, Orissa, India 4 Rajib Gandhi National Fellow, P.G.Departm ent of Environmental Sciences, Sam balpur University, Jy oti Vihar -768 019, O rissa, India 5 Departm ent of factory and Boilers, G overnment of Orissa, Bhub aneswar, Orissa, India Abstract: A detailed field survey w as undertak en in 20 villages w ithin 05 Km ’s radius of Bargarh Cement W orks to assess the socio-economy profile, health and n utrition status and quality of life of peo ple in order to assess the contribution of BCW on their responsibility towards the comm unity. T he survey was organized to collect inform ation on socio-eco nom ic variables at the village level from census data of the governmen t as well as household level data through questionnaire method. The study focused primarily the village level an alysis and variations across social groups as well covering three aspects viz., Socio-economic profile of the region and the people, health status of people and assessment of Quality of life of the people and the villages. As regards the socio-economic profile the study attempts to present village wise analysis of de mog raphic characteristics, caste distribution, occupational structure, availability of social amenities on the basis of second ary data. Village-wise malnutrition status in terms of weight for age and Body Mass Index of the sample belonging to < 5 years, 5-16 years and >16 years of age were calculated. When scores were assigned on per cent of normal population at each age-group in each village, Patikarpali, Chandipali Halanda and Deultunda scored more than 80%, Gudesira, Turunga, Baulsimgha, Haldipali, Nuagudesira scored between 60-80% and rest <60%. T he villag es like B isalpali, T ukurla Gh upali, Khaliapali, Murum kel, A mba pali, Deogaon, Bard ol, Padhanpali, Katapali, Piplipali requires immediate intervention to meet their nutritional requirem ents through awareness campaign and training. Prevalence of higher proportion of normal children in almost all villages might be attribu ted to lon ger du ration of breast feeding in the locality. In all the age groups, proportion of females with malnutrition has been more than the males. The percentage of females with normal nutritional status were 9, 14 and 76.3 % in 0-5, > 5-16 and > 16 years catego ry respectively in compa rison to 20.5, 29.9 and 76.3% in male category. Table 32 reveals that around 21% from male child category (0-<5 yrs) and 30% from age-group of >5-16 yrs were norm al in nutritional statu s. The percentage of norm al female children w ere still less, i.e only 9% and 14 % respectively. The children suffering from severe malnutrition was 25% in the agegroup of >5-16 years w here as it was 9.7% in 0-<5 yrs ag e-group. Less proportion of children b elong ing to malnourished group (Fig. 2) may be d ue to prolonged breast-feeding prac tices prevalen t in the area. A slightly higher proportion of the population belonging to age –group 5-16 years showed poor nutritional status (severe malnutrition) in comparison to <5 years as well as >16 yea rs. This perha ps indicates that this sec tion of people was not able to meet the nutritional needs as per the requirement for the growing period. On the basis of the value function base d on 14 indicators wh ich also include the socio-economic p rofile , the QOL (Quality of Life Index) of different households were computed for the different villages . It is observ ed that for the over all sample households the quality of index stands at 4.19, which is considered to be “Average” in the value function. Village- wise it is noticed that the villages with slightly improved position were Gudesira, Turunga, Deogaon, B ardol, Katapali, C handipali and Nuagudesira, where the status is considered “Fair”. On the other hand villages wh ich witness low est quality of life and recorde d as “Poo r” were Bisalpali, Piplipali, Tuku rla and Halanda. Rest of the 9 villages are considered having “Average” quality of life. Highest quality index was registered by ge neral caste followed by OB C and the lowest index is noted for SC followed by ST. However only general caste recorded a “fair” quality of life compared to all other groups identified as having “Average” quality of life.Occupation wise it is noticed that highest index was registered by service class followed by business and household industry (with a “fair” quality of life) and the lowest was noted in case of persons dependent on forestry (with a “poor” quality of life) followed by non- agricultural labour, artisans and agricultural labour, with “A verage” quality of life. Cultivators were found to be hav ing a “A verag e” qu ality of life as w ell. Key w ords: Cem ent industry, people, socio-ecolog ical, health and nu tritional status and quality of life Corresponding Author: P.C. Mishra, P.G. Department of Environmental Sciences, Sambalpur University, Jyoti Vihar -768 019, Orissa, India 93 Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci., 1(3): 93-110, 2009 of med ical assistance to nearby villages, this is usually minimal and restricted to organizing occasional medical camps for conducting cataract, family planning related operations and pulse polio programme. As a rule most cement companies do not allow local communities access to the hospital they set up for the staff. Some companies support local schools or install tube we lls for farmers, create reservoirs to store water in the mine lease areas but rarely local comm unities have ac cess to it. How ever, there are industries who have contributed positively for the com mun ity development. J K Lakshmi Cement Limited and Prison Cement Limited provide free medical assistance in their hospitals to the local people. Cement Division of Sanghi Industries Limited located in a waterscarce area on the coastal belt, has set up a desalination plant, which is a major source of water for the local community. Hirmi Cement Works of the Ultratech Group has floated an NGO, Grihini, which is involved in helping local women to produce and market items like papads and hand made pickles. Som e com panies hav e tried to train villagers and import them with certain skills so that they become drivers, masons, engine mechanics and electricians (CSE , 2005). Studies on Socioe conomic profile have been made by Kumar (1996) for West Bokaro M ining Complex and Prusti (1996) for Jharia Coalfields. Work on the concept of quality of life grew ou t of the social indicators movement of the 1960s (Day and Jankey, 1996) and investigators started u sing a social indicator appro ach to define what QO L meant to them. H owe ver, subsequently many researchers adopted both subjective and objective approaches to assess QOL available on wide literature on the subject (Echevarria-Ush er, 1999; Singh 1989, 1999; Forget and Lebel, 2001; Noronha and Nairy, 2005; Sheykhi 2006). Sheykhi (2006) made an extensive sociological study of Quality of Life by examining the fertility behaviour from a multidimensional perspective. Echevarria-Usher (1999) equated health, in its fullest and multicultural connotation, with we ll-being or quality of life. Understanding of QOL needs exploration of relationship between various components-economic, biophysical, socio-cultural and political- to arrive at the priority determinan ts of health and wellbeing (Saxena et el., 1998 ; Forget and Lebel, 2001). Noronha and N airy (2005) adopted participation process, case histories, biomedical health analysis and spatial and environmental analy sis in develop ing a Q uality of Life too l. Against this background, a detailed field survey was undertaken in 20 villages within 05 Km’s radius of Bargarh Cement W orks to assess the socio-economy profile, health and nutrition status and quality of life of people in order to assess the contribution of BCW on their responsibility towards the community. INTRODUCTION Cement plants have both environmental and social obligations to fulfil. Cemen t making op erations exert a major impact on local environment as they involve several pollution generating activities like mining, incineration, power generation, grinding and handling of final product before transportation to the market. It is important to kno w how it carries out its social obligations and provides benefit to the local communities where it is located through the profit it makes. Even the most efficient manufacturing plant will have a high impact on the environment and on the people working in and living near it. This industry uses resources that are nonrenew able (raw material and energ y), changes the land use and local ecology forever due to its mining activities and manufactures a product that is not recyclable. Nevertheless, if cement is a product that modern society desp erately needs, then society and local commu nity must be prepared for some adverse impacts. It is thus important to define the meaning of an “acceptable trade-off and benchm ark pe rformance ” of compa nies ag ainst it. Under ideal circumstances, cement plants should not be located near human ha bitations. But in India, most of the cemen t plants are in the vicinity of v illages and sm all towns. In some cases towns have come up around plants. There are several exa mples in India including Orissa Cement Limited, Rajgangp ur, Jharsuguda Cement Works of Ultratech Cement and Bargarh Cement Works of ACC Ltd. As a result, these habitations more often than not bear the brunt of dust generated from the plants. Strong winds carry this dust over a long distance and blanket the surrounding villages with it. A n ave rage ceme nt mill transports thousands of tons of raw materials and cements every day leading to dust emissions during movement of trucks on Kuccha village roads. The emissions from the plants have also led to deterioration in air quality and soil productivity, although the plants in most of the cases meet the regulatory standards. Local communities have several expectations from industry. There is reason for this. W hen industry starts setting up a manufacturing plant and acquires land for mining, it makes all kinds of tall promises to the local people for the development of the area and job opportunities. However, it is now clear that the capacity of large-scale cement plants to provide formal employment is truly limited. When these prom ises are not satisfactorily fulfilled, conflict with local communities follows. The expectations of the local communities increase when the industry is seen to impact the local environment adversely. They rightfully feel that the impact of industry on the ir life support system, like water and air, shou ld be adequately com pensated. There are many areas availab le for the authority of a cement industry to provide basic needs of the local community. In India, cement plants are often located in areas where the health infrastructure is poor or nonexistence. W hile most of the indu stries provide som e form MATERIALS AND METHODS The present study was designed to cover general aspects, aspects of ed ucation, availability and access to 94 Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci., 1(3): 93-110, 2009 Table 1: Parame ters used for the computation of the Quality of Lif e index. C Housing (Type & Number of room) C Source of Water used C San itary fa cilities A vaila ble C Food and nutrition intake C Health and safety status C Educational status C Medical facilities C Transport and communication facilities C Fu el an d en ergy ava ilability C Assets possessed C Own transportation means C Per-capita income C Recreational facilities C Malnourishment The minimum desired level of score for the abov e param eters for a fair living condition was defined with a value of 0.5 on a scale of 0 to 01. All the parameters have been given an equal weightage and the total score of Q OL Ind ex is 1 4. The classification o n the b asis of total sc ore used for analysis is as follows: <3 - Poor, 2. >3-5-A vera ge, 3. >5-7-Fair/Satisfactory, 4. >7-10-Good, 5. >10-14-Very good various facilities, asset position, occ upational structure, income gene ration and health status. The survey was organized to collect inform ation on socio-eco nom ic variables at the village level as well as hou seho ld level. The village level data were collected from revenue offices, panchayat office, censuses while the house hold level data we re collected through a questionnaire method. The sample survey were conducted covering about 20 households from each village belonging to different caste groups, occupation groups and land size groups to make it approximate to a stratified sampling method. The study focused primarily the village level analysis and variations across social groups as we ll covering three aspects viz., Socio-eco nom ic profile of the region and the people, health status of peop le and assessment of Quality of life of the people and the villages. As regards the socioecon omic profile the study attempts to present village wise analysis of de mog raphic characteristics, caste distribution, occupational structure, availability of social amenities on the basis of secondary data. The sample survey data have been used to present the socio-economic status with regard to demographic features, educational status, occupational structure, facilities and living conditions, food intake pattern, asset ownership structure, and income distribution. Following data on soc ioecono mic profile were collected at village-lev el. C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C Severe underw eight = < 16.0 , Moderate = 16.0- 17.0, Mild= 17.0- 18 .5 , No rmal= >18.5 W eight for Age (WFA) was calculated as (Actual W eight/ Standard weight) X 100. The Gomez classification used to classify the weight status is as follows.(Park and Park 1991). Grade -III= < 60% , Grade-II= 61% - 75% ,Grade-II= 76%- 90%, Normal= > 90% Male, Fem ales, Sex Ratio, Average family size, % L iteracy, Caste Co mpo sition, Health care facilities available, W ater availability and sanitation facilities, Edu cational facility, Craft facility, Land use Pattern, Comm unica tion facilities (transport), Recreational facilities, Fuel and E nergy facilities, Income p attern and O ccup ational structure. The Quality of life index (QOL) has been computed for different villages with broadly the methodology adopted in a study “Quality of Life index of the Mining Areas” by Saxen a, et al. (1988) with modification by Mishra et al. (2008, 200 9). The parameters in Table 1 are included for the computation of Qua lity of Life Index. Scaling of different indicators were made to calculate the Q uality of Life Index (Table 2). RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Socio-economic Profile: General particulars of the Region: Out of the 20 villages from which sample households have been selected, 15 villages are revenue villages for which Census information are available in Town & Village Directory (Primary Census Abstract during 1991 and 2001). On the basis of the information a general profile of the region ha s been presented in Tab le 3. The total number of households in the 15 villages is 5722 as per 2001 census with an increase of 21.4% over 1991 census. During the same period total population increased by 15 .46% . One also notices v ariations in grow th of population in different villages. All the villages registere d growth of pop ulation excepting M urum kel. Villages which registered significant rise in population are Padhanpali, Bardol, Chandipali and Halanda. The sex ratio for the total of all villages has marginally decreased Health status of the people were assessed pertaining to frequency of occurrence of various diseases and level of malnourishment through anthropometric study. The study sought to examine the incidence of various types of common ailments as well as chronic diseases v iz., air borne diseases, water born e disea ses an d para sitic infections. The anthropometric study analysed the weight and height measurements of each me mbe r of the sa mple households and indices such as Body mass Index for persons above 16 years and Weight for age (WFA ) for children less than 16 years both for M ale and fem ale separately w ere calculated . Body Mass Index (BMI) was computed as weight/(height in mt) 2 . The classifica tion used to classify the health status is as follow s.(Park and P ark 1991 ). 95 Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci., 1(3): 93-110, 2009 Table 2: Method used for the assessment of quality of life index Parameters considered Values assigned --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------C Housing Pucca –3 rooms 00 .5 Mixed –>5 rooms 00 .5 Kachha - > 10 rooms 00 .5 Lower and higher values are assigned according to availability of rooms C Sanitary facilities No facility 0 Pro per fa cility 0.5 For additional facilities higher values are assigned C Roads and Transport Facilities Good roads, bus and railway service Good roads and proper bus facilities Only railways and bus facilities C Prevalence of Common D iseases Suffering from Co mmon d iseases Suffering from No major diseases No diseases Do cto r + s pe cial izat ion 0.8 C Fuel and Energy used Coal + electricity + Gas Co al + e lectricity Coal Wo od + coal Wood C Assets possessed amounting to Rs.< 10,000 Rs.10,000-30,000 Rs.30,000-50,000 Rs.50,000-1 lakh Rs > 1 lakh C Per C apita Inco me p er m onth Rs. < 1000 Rs. 1000-1400 1400-1800 1400-1800 1800-2300 2300-5000 5000-10000 10000-20000 20000 above Table 3: General profile of villages of the region Village No. of Hhs --------------------------1991 2001 Ka tapa li 1150 1267 Pad han pali 378 536 Deogaon 261 299 Turunga 244 259 Bardol 931 1274 Ch and ipali 76 100 Ha ldipa li 100 120 Piplip ali 161 236 Gu desira 712 787 Baulsingha 105 140 Deultunda 107 155 Murum kel 97 92 Bia salpa li 122 112 Halanda 75 125 Tu kur la 193 220 G.Total 4712 5722 1.0 0.75 0.5 0.3 0.5 1.0 Parameters considered Values assigned --------------------------------------------------------------------------------C Source of Water Tu be w ells or o wn we lls 0.5 Villa ge w ell 0.3 For additional own source of water higher value is assigned C Food type Good (Rice+Pulses+curry) 0.5 M o d er at e ( Ri ce +p u ls es + G L V ) 0.3 P o or (R ic e+ O n io n +G L V ) 0.1 Higher values area assigned as per availability of non-vegetarian foo ds a nd oth er p rote in fo od s. C Vehicles Possessed Cy cle 0.3 Scooter/ motor cycles 0.5 Four wheelers> 0.7 C Me dical Treatment Facilities No availability of medical facilities 0 Doctor 0.2 Dispensaries 0.5 Do ctor + D ispensa ry C Entertainment Only TV TV + Cinema Cinema + Community recreations TV + C inem a+ C om mu nity 1.0 0.75 0.5 0.3 0.2 0.2 0.35 0.5 0.75 1.0 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 C Educational Qualification Illiterate < M atricu late M atricu late Higher education 0 0.3 0.5 0.7 C Malnourishment >80%-Normal Population 60 - < 80 % - Normal Population 40 - < 60 % - Normal Population 20 - < 40 % - Normal Population <20%-Normal Population 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 Population -----------------------------------------1991 2001 %increase 5618 5853 4.18 1969 2672 35.70 1304 1326 1.69 1169 1247 6.67 4342 6039 39.08 376 492 30.85 537 573 6.70 899 994 10.57 3291 3543 7.66 605 651 7.60 670 758 13.13 437 416 -4.81 445 486 9.21 482 581 20.54 1042 1139 9.31 23186 26770 15.46 from 960 in 1991 to 956 in 2001. H igher sex ratio of a village being an index for higher importance of women, it is noticed that the villages witnessing significant decline 1.0 S ex ra tio % ------------------------1991 2001 928 980 925 940 1003 988 1058 976 941 939 1032 922 960 956 929 919 954 920 958 876 1030 1038 1042 990 1139 1122 984 1097 985 921 960 956 literates --------------------------1991 2001 48 .1 62 .7 43 .7 54 .4 41 .7 62 .4 46 .5 60 .3 45 .7 56 .2 26 .3 48 .0 38 .4 57 .2 35 .5 56 .7 41 .3 55 .8 38 .5 45 .3 36 .1 44 .2 40 .0 43 .8 39 .1 42 .8 29 .7 24 .8 47 .8 56 .4 43 .5 56 .1 of sex ratio over time were Deogaon, Turunga, Baulsingha, and Murumkel. Regarding spread of education in the locality it is observed that the rate of 96 Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci., 1(3): 93-110, 2009 Table 4: Caste distribution of people in the villages Village %SC in Population ------------------------------------1991 2001 Ka tapa li 16.63 19.85 Pad han pali 31.89 29.75 Deogaon 16.18 18.17 Turunga 20.02 18.52 Bardol 26.62 32.79 Ch and ipali 36.17 33.74 Ha ldipa li 14.15 26.53 Piplip ali 0.67 1.41 Gu desira 25.58 30.06 Baulsingha 28.93 30.72 Deultunda 16.12 30.74 Murum kel 8.92 10.58 Bia salpa li 14.83 12.14 Halanda 28.84 31.33 Tu kur la 15.55 15.28 G. Total 21.19 25.02 %ST in Population -------------------------------------1991 2001 3.38 2.97 5.33 7.15 21.86 20.66 22.58 28.79 13.40 11.77 11.44 16.26 7.64 8.73 3.11 2.72 9.66 8.66 29.92 29.19 29.85 29.16 46.68 49.52 25.84 27.78 10.17 8.43 17.37 17.73 12.02 11.86 Table 5: Occupational distribution of the people in the region Village % W ork ers to % cultiv ators to population M ain w orkers ---------------------------------------------------------------1991 2001 1991 2001 Ka tapa li 32.98 38.56 16.32 13.40 Pad han pali 34.94 35.52 18.37 14.74 Deogaon 26.61 39.97 37.18 48.26 Turunga 35.67 32.64 13.67 19.25 Bardol 38.90 38.75 20.84 12.04 Ch and ipali 26.60 49.59 53.00 30.99 Ha ldipa li 54.56 44.50 22.73 29.91 Piplip ali 32.59 56.34 90.24 58.48 Gu desira 44.24 46.99 25.62 20.41 Baulsingha 46.61 39.63 44.06 45.64 Deultunda 48.51 52.64 61.64 23.88 Murum kel 53.55 50.96 59.63 54.64 Bia salpa li 54.16 34.98 38.69 43.18 Halanda 64.11 46.82 65.67 40.00 Tu kur la 33.11 47.85 54.81 46.90 G.Total 38.26 41.33 29.45 21.82 literacy for all the villages taken together increased from 43.5% in 199 1 to 56 .1% in 200 1. W hile all the villages have registered increase in the rate of literacy over time excepting Halanda , the villages registering very high grow th in literacy w ere G udesira, Haldipali, Chandipa li, Deogaon an d Katapali. % Ag ril labo ur to M ain w orkers ---------------------------------1991 2001 22.68 21.85 15.89 7.06 37.46 1.16 34.77 24.06 32.62 10.73 41.00 33.80 69.55 31.78 2.09 29.53 42.05 34.13 50.57 45.64 19.40 39.40 29.19 34.02 47.62 31.82 24.38 40.00 26.24 28.68 30.95 21.87 % SC & ST in Population ------------------------------------1991 2001 20.01 22.83 37.23 36.90 38.04 38.84 42.60 47.31 40.03 44.56 47.61 50.00 21.79 35.25 3.78 4.12 35.25 38.72 58.84 59.91 45.97 59.89 55.61 60.10 40.67 39.92 39.00 39.76 32.92 33.01 33.20 36.88 % M argin al w ork ers to Total w orkers ------------------------------------1991 2001 10.04 23.97 0.29 13.49 0.00 51.13 0.00 8.11 5.98 28.29 0.00 41.80 24.91 58.04 2.05 38.93 10.99 27.33 7.45 42.25 28.62 16.04 31.20 54.25 30.29 48.24 34.95 59.56 0.58 52.66 10.12 30.53 Occupational distribution: The occupational distribution of local population can be examined from Table 5 presented below. Occupational distribution has been presented at two p oints of time viz., 1991 and 2001. It is observed that in total of all the villages work participation rate has increased from 38.26 % in 1991 to 4 1.33% in 2001. Among the villages, work participation rate declined in Turunga, Ha ldipali, B aulsingha, Murmukel, Bisalpali, and H alanda. Fu rther in 2001 relatively low participation rate was observed in Padhanpali, Turunga and Bisalpali. Among the main workers, one notices declining depe ndence o n agriculture. In the total of all villages, the dependence declined from 60.40% of the main workers (engaged as cultivators & agricultural labour) in 1991 to nearly 43.69% in 2001. The decline was found both in case of agricultural labour from 30.95% to nearly 21.87 % and of cultivato rs in total m ain worke rs declined from 29.45 % in 1991 to 22 1.87% in 2001. Village wise relatively higher dependence on agriculture was noticed in Chandipali, Haldipali, Piplipali, Baulsingha, Deultund a, M urum kel, Bisapali, and Halanda. Relatively high proportion of main workers engaged as agricultural labour is still found in Ch andipali, Caste distribution: Caste distribution of the people in the region can be examined from Table 4. It is observed that SC & ST constituted about 33.20% of the total population in the total of all villages. Of these backwa rd populations, SC constituted 21.19% and ST 12.02%. The villages with relatively h igher SC population w ere Padhanpali, Bardol, Chandipali,,Gudesira, Baulsingha, Deultunda and Halanda. The villages with higher ST population were Deogaon, Turu nga, Baulsignha, Deultunda, Murm ukel and Bisalpali. The increase in SC population is relatively very high in the villages of Haldipali and Deultunda. On the other hand one notices marginal decline of ST population in most of the villages. There was marginal increase of ST population only in Padhanpali, Chandipali an d Bisalpali. 97 Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci., 1(3): 93-110, 2009 Table 6: Social amenities in the region Village Education Medical Ka tapa li P,M .H,C P,H ,C Pad han pali P,M 5-10 Deogaon P ,M H MCW Turunga P,M CHW Bardol P,M 5 Ch and ipali P 5 Ha ldipa li P CHW Piplip ali P 10 Gu desira P,M ,H CHW Baulsingha P 10 Deultunda P 5 Murum kel P,M ,H CHW Bia salpa li P CHW Halanda P 5 Tu kur la P,M CHW Drinking water W,TW W,TK,TW TWRC TK,TW TK,TW TK,TW W,TK,TW W,TK,TW W,TK,TW W,TK,TW W ,TK ,TW ,R W ,TK ,TW ,R W,TK,TW W .TK ,TW ,R W ,T,K ,TW ,R Table 7: Social amenities in the villages under study Village Education Medical Sources of water Murum kel PH NO Bardol APH PP Kh aliap ali APH NO Gh ulipa li NO NO Pad han pali P NO Piplip ali P NO Ch and ipali NO NO Deogaon P,H DIS Turunga P,H NO Patik arpa li P NO Ha ldipa li P NO Am bap ali A,P ,H DIS Gu resira P,H NO Nu agure sira P NO Ka tapa li APHC D IS ,F A C Bisa lpali P NO Halanda P NO Tu kur la NO NO Deultunda NO NO Baulsingha NO NO Co l.1- P -Pri ma ry, H -H igh Sc ho ol, C -C olle ge , Co l.3- W -W ell, T k- T an k, T w- Tu be we ll, R -R ive r, Co l-5 E D- Ele ctrif ied , P,W,T,TW P (B ) P,W,T,C,TW P (B ) P,W,TW K(B) P,W ,TW ,C K(B) P,W ,TW ,C K(B) P,W ,TW ,C K(B) P,W ,TW ,C P (G ) P,W ,PW S,T W ,C P (G ) P,W ,TW ,C K(B) P,C K(B) P,W ,C K(B) P,W ,TW ,PW S,C P (B ) P,W ,TW ,C P (B ) P,W ,TW ,C K(B) P,W ,T,T W ,C P (B ) P,W ,TW ,C K(B) P,W,T,TW K(B) P,W,TW K(B) P,W ,T,T W ,C K(B) P,W ,TW ,C K(B) Co l.2- P P- P riva te P rac tition er, H -H osp ital, F AC - Fir st Co l.4- P - Pa cca , K- Ka ch ha , Col-6 BS- Bus service. Gudesira, Baulsingha, Deultunda, Murumkel, and Halanda. It is how ever interesting to notice that proportion of marginal w orkers in total workers has increased from 10.12% in 1991 to 30.53% in 2001 for the total of all villages. Village wise relatively higher increase of marginal workers is found in Deogaon, B ardol, Chandipali, Haldipali, Piplipali, Baulsimgha and Tuk urla.A a decline in the proportion of ma rginal work ers was noticed only in Deultunda village . The general declining dependence on agriculture may be due to the mining and industrial activities in the region. However, the increasing number of marginal worke rs indicates lack of employment opportunity in the region. Po st & Tel. PO 5 PO 5 PO 5 5 5 PO 5 5 5 5 5 PO Nature of Road Elec tricity EA EA EA EA EA ED EA ED EA ED ED ED ED ED ED Elec tricity ED ED ED ED NO ED ED ED ED ED ED ED ED ED ED ED ED ED ED ED A id C en tre, Communication BS 5 5 5 BS 5 BS 5 5 BS 5-10 10 10 5 5 Communication Bus service NO BS NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO BS NO NO NO NO NO had only Primary school. Only 8 villages (Katapali, Turnga, Deogaon, H aldipali, Gud esira, M urum kel, Bisalpali and Tukurla) had some medical facility in the village but in the rest 7 villages medical facilities were available at a distance of 5 kms or more. The source of drinking water had been Wells, Tanks and Tubewells in 10 villages , W ell and Tubewell has been reported as source of water in Katapali and Tank & T ubewell in villages of Bardol, Chandipali and Turunga. River was also a source of water in 5 villages. It was noticed that only 5 villages (Katapali, Deogaon, Bardol, Gudesira and Tukurla) had post offices while for rest 10 villages postal services were available at a distance of 5 kms or more . All the villages were electrified with 8 villages having electrification for domestic consumption. Regarding communication facilities Bus services were available in 4 villages (Katapali). For the rest of the villages communication services were available at a distance of 5 kms or mo re. The village survey results regarding social amenities during the current period of survey are presented in Social amen ities: The social amenities in the region as per 1991 census is presented in Table 6 .It is observed that of the 15 villages 1 village (Katapali) had Primary, Middle, High schools and College, 3 villages (Deogaon, Gud esira and Murumkel) had Primary, Middle, and High schools, 4 villages (Padhanpali, Turunga, Bardol, Kuturla) had Primary an d M iddle schoo ls and the rest 7 villages 98 Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci., 1(3): 93-110, 2009 Table 8: Th e list of villages with respective sam ple sizes Bargarh Block No. of Bhatli Block No. of Households Households 01. K atap ali 20 11. P atika rpali 20 02. P adh anp ali 20 12. A mb apa li 20 03. Deogaon 20 13. N uagu resira 20 04. Turunga 20 14. K halia pali 20 05. Bardol 20 15. Baulsingha 20 06. C han dipa li 20 16. Deultunda 20 07. H aldip ali 20 17. Murumkel 20 08. P iplipa li 20 18. B isalpa li 20 09. G udes ira 20 19. Halanda 20 10. G hulip ali 20 20. T uku rla 20 Total 200 Total 200 Grand Total 400 Table 7. No educational facilities were found in 5 villages (Gh ulipali, Chandipali, Tukurla, Deultunda and Baulsimgha). Only Primary schools were found in 7 villages (Padhanpali, Piplipali, Patikarpali, Haldipali, Nuaguresira, Bisalpali and Halanda). Primary schools and High schools w ere fou nd in 7 villages (Murum kel, Bardol, Khaliapali, Deogaon, Turunga, Am bapali and Guresira). Medical facilities in some form were available only in 4 villages (Bardol, Deogaon, Ambapali and Katapali). The sources of water in most of the villages have been Ponds, w ells and tube w ells and Can al. W hile roads to the villages were good in 2 villag es (Chandipali and Deogaon ), pucca roads were found in 7 villages. There was provision of electricity in 19 villages. Bus services were availab le only in 2 villag es. A college was located in on ly one village, K atapali. Caste distribution: The caste d istribution of the sa mple households (Table 11) reveals a predominance of OBC category (47.25%) followed by SC (35.25%), G eneral (9.25%) and ST (8.25% ) . General particulars of the sample households: The sample survey was conducted by canvassing a structured questionnaire amo ng the sample resp ondents to e licit information on ge neral particulars, occupation, education, mode rn facilities, nature of dwelling, source s of water, mode of fuel used, nature of food-intake, asset position, source of income, indebtedness, land ownership, production of crop s, labour disposition, physical status, health cond itions and ailments and nature of medical assistance received. In the present report attempt has been made to assess the aggregative analysis of the 400 households selecting 20 households each randomly from the 20 villages,15 villages mentioned in the preceding section and additional 5 villages- Khaliapali, Patikarp ali, Am bapali, Ghulipali, N uaguresira (Table 8). Education: The educational status of family members of sample respondents village-wise is presented in Table 12.The level of literacy was found to be 33.2%among the respondents.Female literacy was found to be significantly higher compared to males. There exist variations among the villages in the educational status. Highest male illiteracy was found in Deulatunda village (61.76% ). Highest female illiteracy (> 60%) w as found in Patikarpa li, Murumkel, Ambapali, Deultunda, Halanda, Nua gudesira and Turunga. One observes that the level of education of bulk of the population (53.16%) w as up to Primary or middle sch ool level with about 9.30% having education up to secondary school and only 4.34% as college educated. Villages having higher proportion of persons with primary or middle school edu cation were Gudesira, Deogaon, Bardol, Baulsingha, Haldipali and Tukurla. In all the villages, lev el of prim ary & midd le education was foun d high er for males co mpa red to females excepting in Khaliapali, Bardol, Baulsingha, Haldipali and C handipali. Higher level of secondary education for males compared to females was found in all the villages excepting Ghupali, Murumkel, Katapali and Nuaguresira. Villages with relatively higher level of secondary educ ation w ere K atapali, Chandipa li and Haldipali. Similarly in case of college education all the villages registered higher male college educated excepting in Murumkel, Ambapali and Baulsingha. Relatively higher level of college edu cation wasfoun d in G hupali, Haldipali an d Chandipali. Age and Sex: The age and sex distribution of the sample respo ndents are presented in Table 9. Of the total sam ple respo ndents almost all were males with only one female. Majority of the respondents (76.5%) were in the age groups of 30-60 years. The age and sex composition of the total fam ily members of the sample respondents can be examined from Table 10. The sex-ratio was found to be low (721) for the total respondents. Highest sex-ratio is found in the village Katapa li (1024). Relatively higher ratios were found in the villages of Piplipali (897), D eultunda (88 2), Haldipali (868) and Nuaguresira (838) and lower ratios in Chandipali (346), Bisalpali (592), Murumkel (617) and Turunga (643). The age-wise distribution of population of sample households in different villages reveals that about 46.78% of the population belonged to the age group of less than 30 years or the young population. The villages with relatively more young population (more than 55%) were Khaliapali, Gudesira, Deogaon, Bardol and Padhanpali. Low level of young population is found in the villages of Deultun da, K haliapali, Baulsingha, Halanda and Turunga. Occupation: The oc cupational structure of the samp le respo ndents presented in Table 13 reveals that about 38.25% of the total responden ts depend ed on ag riculture as primary occupation. Nearly 24.75% were daily wage labour (agricultural as well as non-agricultural). About 17.25% were dependent on forests or were artisans followed by 10.75% of the respondents being service holders, while 1.5% were engaged in Business or trade, 7.5% were dep endent on other occup ations. 99 Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci., 1(3): 93-110, 2009 Tab le 9: A ge a nd s ex d istribu tion o f sam ple re spo nde nts Sex ------------------------------------------Village M ale Fem ale Total Gh upa li 100 100 Kh aliap ali 100 100 Patik arpa li 100 100 Murum kel 95 5 100 Gu desira 100 100 Am bap ali 100 100 Turunga 100 100 Deogaon 100 100 Bardol 100 100 Pad han pali 100 100 Ka tapa li 100 100 Baulsimgha 100 100 Bisa lpali 100 100 Piplip ali 100 100 Ha ldipa li 100 100 Ch and ipali 100 100 Tu kur la 100 100 Halanda 100 100 Deultunda 100 100 Nu agud esira 100 100 Total 99.75 1 100 Age groups -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------<20 20-<30 30-<40 40-<50 50-<60 60 & above Total 10 50 10 30 100 10 40 40 10 100 20 15 30 25 10 100 25 45 10 20 100 5 35 25 15 20 100 15 30 20 30 5 100 5 35 50 10 100 5 30 35 25 5 100 10 35 45 10 100 10 15 45 30 100 10 30 30 20 10 100 10 5 25 40 20 100 10 40 20 20 10 100 10 10 45 25 10 100 5 40 5 30 20 100 5 15 20 5 30 25 100 15 5 25 35 20 100 5 40 35 20 100 30 40 30 100 30 30 35 5 100 0.25 7.25 25 25 26 .5 13 .5 400 Tab le 10: Age and sex comp osition of family members of sam ple resp ond ents Village M ale Fem ale Sex -ratio Population below 30 ye ars Gh upa li 42 28 667 41.43 Kh aliap ali 51 40 784 56.04 Patik arpa li 31 22 710 33.96 Murum kel 47 29 617 51.32 Gu desira 56 32 571 55.68 Am bap ali 34 25 735 38.98 Turunga 42 27 643 37.68 Deogaon 48 36 750 57.14 Bardol 46 38 826 59.52 Pad han pali 40 32 800 56.94 Ka tapa li 42 43 1024 47.06 Baulsimgha 55 33 600 34.09 Bisa lpali 49 29 592 50.00 Piplip ali 39 35 897 50.00 Ha ldipa li 38 33 868 46.48 Ch and ipali 52 18 346 47.14 Tu kur la 35 27 771 48.39 Halanda 38 29 763 37.31 Deultunda 34 30 882 29.69 Nu agud esira 37 31 838 42.65 Total 856 617 721 46.78 Table 11: Caste distribution of sample households Caste groups -----------------------------------------------------------------Village SC ST OBC General Othe rs Total Gh upa li 50 50 100 Kh aliap ali 100 100 Patik arpa li 100 100 Murum kel 40 35 25 100 Gu desira 40 60 100 Am bap ali 50 10 40 100 Turunga 20 10 70 100 Deogaon 15 10 65 10 100 Bardol 5 15 75 5 100 Pad han pali 25 75 100 Ka tapa li 100 100 Baulsimgha 30 40 30 100 Bisa lpali 65 5 30 100 Piplip ali 60 30 10 100 Ha ldipa li 5 10 85 100 Ch and ipali 100 100 Tu kur la 85 15 100 Halanda 60 40 100 Deultunda 85 15 100 Nu agud esira 10 90 100 Total 35.25 8.25 47.25 9.25 100 The occu pation al structure of m emb ers of sa mple households (Table 14) shows a work participation rate of 43.79% of total respondents. The dependence on agriculture was limited to 65.89% (31.63% as cultivator and 34.26% as agricultural labour) of the total workers. Nearly 13.64% were engaged as non-agricultural labour, 9.61% as service holders, 2.79% in business and 1.24% in other occupations. While one observes not much variation in work participation rate among the villages excepting in case of Patikarpali, Deultunda, Nuagudesira and Halanda. Villages with higher proportion of cultivators were Khaliapali, Murumkel, Gudesira, Katapali, Baulsingha, Haldipali and Nuagudesira. The share of agricultural labour in total workers was relatively high in Patikarpali, Turunga, Halanda and Deultunda. Proportion of non-agricultural labour population was relatively high in Deo gaon, Bardol and Tukurla. Relatively higher proportion of service holders was found in Bard ol, Bisa lpali, Piplipali, Haldipali and Chandipali. Similarly relatively more people were engaged in business in Bisalpali and Tukurla. Other occupations we re relatively more impo rtant in A mba pali. Given the occup ational structure w ith significantly higher engagement of workers in non-agricultural activities for the sample households, it will be interesting to analyze the level of employm ent of family members of the sample households from Table 15. The average mandays employed for total of all sample households was 215 days. However, relatively higher level of employment was found in Ghupali, Khaliapali, Murumkel, Gudesira, Deogaon, Bard ol, Pad hanpali, Baulsingha, Piplipali, Haldipali, Chandipali, Chandipali and Tukurla. The villages with relatively low er level of emp loymen t were Patikarpali, Deultunda and Turunga. 100 Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci., 1(3): 93-110, 2009 Tab le 12 : Ed uca tiona l status of fa mily m emb ers o f sam ple re spo nde nts Village Illiterate Prim ary & M iddle -------------------------------------------------------------------M F T M F T Gh upa li 9.52 46.43 24.29 64.29 32.14 51.43 Kh aliap ali 25.49 37.50 30.77 50.98 55.00 52.75 Patik arpa li 58.06 72.73 64.15 41.94 27.27 35.85 Murum kel 48.94 68.97 56.58 42.55 17.24 32.89 Gu desira 25.00 56.25 36.36 71.43 43.75 61.36 Am bap ali 50.00 68.00 57.63 47.06 28.00 38.98 Turunga4 7.62 77.78 59.42 50.00 22.22 39.13 Deogaon 16.67 19.44 17.86 68.75 66.67 67.86 Bardol 8.70 13.16 10.71 73.91 76.32 75.00 Pad han pali 32.50 59.38 44.44 67.50 40.63 55.56 Ka tapa li 16.67 34.88 25.88 52.38 39.53 45.88 Baulsimgha 5.45 6.06 5.68 70.91 87.88 77.27 Bisa lpali 24.49 41.38 30.77 59.18 55.17 57.69 Piplip ali1 5.38 37.14 25.68 58.97 57.14 58.11 Ha ldipa li 7.89 3.03 5.63 44.74 78.79 60.56 Ch and ipali 7.69 22.22 11.43 25.00 44.44 30.00 Tukurla1 1.433 3.33 20.97 77.14 66.67 72.58 Halanda 42.11 72.41 55.22 55.26 27.59 43.28 Deultunda 61.76 63.33 62.50 38.24 36.67 37.50 Nu agud esira 35.14 61.29 47.06 62.16 35.48 50.00 Total 26.05 43.11 33.20 56.54 48.46 53.16 Tab le 13 : Oc cup ation al struc ture o f sam ple re spo nde nts Village Cultivator Daily wage Business Gh upa li 20 55 Kh aliap ali 60 Patik arpa li Murum kel 75 20 Gu desira 55 20 Am bap ali 40 10 Turunga 30 5 Deogaon 50 20 5 Bardol 75 Pad han pali 80 Ka tapa li 30 35 10 Baulsimgha 40 60 Bisa lpali 5 75 Piplip ali 10 85 Ha ldipa li 70 20 5 Ch and ipali 90 Tu kur la 10 Halanda 30 Deultunda 35 Nu agud esira 60 Total 38.25 24.75 1.5 Seco ndary ---------------------------------M F T 11.90 14.29 12.86 15.69 5.00 12.09 0.00 0.00 0.00 2.13 6.90 3.95 1.79 0.00 1.14 0.00 0.00 0.00 2.38 0.00 1.45 14.58 13.89 14.29 10.87 10.53 10.71 0.00 0.00 0.00 19.05 23.26 21.18 21.82 3.03 14.77 8.16 3.45 6.41 23.08 5.71 14.86 18.42 18.18 18.31 38.46 33.33 37.14 5.71 0.00 3.23 2.63 0.00 1.49 0.00 0.00 0.00 2.70 3.23 2.94 10.86 7.13 9.30 Service 5 10 15 25 65 25 20 5 25 10 5 5 10.75 Tab le 14 : Oc cup ation al struc ture o f fam ily me mb ers o f sam ple re spo nde nts Village Cultivator Agril labour Non-agr labour Service Gh upa li 75 0 0 25 Kh aliap ali 69.57 4.35 8.70 13.04 Patik arpa li 0.00 94.23 5.77 0.00 Murum kel 60.00 0.00 16.00 4.00 Gu desira 63.64 9.09 4.55 4.55 Am bap ali 37.93 20.69 3.45 3.45 Turunga 11.54 82.69 0.00 3.85 Deogaon 30.77 0.00 57.69 11.54 Bardol 0.00 0.00 69.23 19.23 Pad han pali 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Ka tapa li 69.57 4.35 26.09 0.00 Baulsimgha 76.19 0.00 16.67 7.14 Bisa lpali 39.29 28.57 0.00 21.43 Piplip ali 26.47 11.76 14.71 23.53 Ha ldipa li 52.17 4.35 13.04 21.74 Ch and ipali 31.03 0.00 6.90 48.28 Tu kur la 0.00 0.00 70.37 7.41 Halanda 10.26 84 .6 20.00 5.13 Deultunda 0.00 100.00 0.00 0.00 Nu agud esira 63.41 29.27 4.88 2.44 Total 31.63 34.26 13.64 9.61 101 Forest/Artisan 5 5 100 5 5 85 60 55 25 17.25 Business 0 4.35 0.00 0.00 9.09 0.00 1.92 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 10.71 8.82 4.35 3.45 22.22 0.00 0.00 0.00 2.79 Othe rs 0 0.00 0.00 4.00 0.00 24.14 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 1.24 College ------------------------------------M F T 14.29 7.14 11.43 5.88 2.50 4.40 0.00 0.00 0.00 6.38 6.90 6.58 1.79 0.00 1.14 2.94 4.00 3.39 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 6.52 0.00 3.57 0.00 0.00 0.00 11.90 2.33 7.06 1.82 3.03 2.27 8.16 0.00 5.13 2.56 0.00 1.35 28.95 0.00 15.49 28.85 0.00 21.43 5.71 0.00 3.23 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 6.54 1.30 4.34 Othe rs 15 25 5 10 20 5 15 10 5 5 5 10 15 7.5 Total 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 Total 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 % share in population 28.57 25.27 98.11 32.89 25.00 49.15 75.36 30.95 30.95 31.94 27.06 47.73 35.90 45.95 32.39 41.43 43.55 58.21 95.31 60.29 43.79 Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci., 1(3): 93-110, 2009 Tab le 15 : Em ploy men t of fa mily m emb ers o f sam ple re spo nde nts Village No. of persons engaged Average man-days in gainful employment employed Gh upa li 20.00 297 Kh aliap ali 23.00 300 Patik arpa li 52.00 91 Murum kel 25.00 302 Gu desira 22.00 293 Am bap ali 29.00 118 Turunga 52.00 99 Deogaon 26.00 309 Bardol 26.00 304 Pad han pali 23.00 300 Ka tapa li 23.00 228 Baulsimgha 42.00 305 Bisa lpali 28.00 292 Piplip ali 34.00 322 Ha ldipa li 23.00 313 Ch and ipali 29.00 307 Tu kur la 27.00 311 Halanda 39.00 102 Deultunda 61.00 92 Nu agud esira 41.00 138 Total 645.00 215 and dinner (Table 20a, b). About 39.5% of the households took puffed rice (local name , Mudhi) and tea in the break fast, 37.75% watered rice (Pakhal) in the break fast. In the lunch 39.0% of the respondents revealed to be taking predominantly only one item (dal/curry) with rice and about 1.75% used to manage eating rice only with onion or sag (e dible lea f ). While 57.75% u sed to take rice, dal and curry, only 1.5% reported taking additionally non-vegetarian item. Regarding evening eating habit one finds that about 55.25% of the respo ndents revealed of not taking anything and 29.5% reportedly took Mudhi/Chuda(flattened rice) with tea. During dinne r while 52.0% reported taking rice with dal or curry and 1.75% rice with onion or sag, about 45.75% used to take rice, dal and cu rry. Asset ownership: The asset ownership position of the different households is presented in Table 21. Most com mon ly owned item was found to be cycle (72.5%) followed by watch/ clock (72.25%). Next in importance were television (50% ), and rad io (48.2 5% ). While only 20.75% of the respondents reported having tape recorder, 10.5% owned two wheelers; barely 0.5% possessed four wheelers. None of the households owned tractor. There was relatively low level of ownership of variou s assets among the sam ple househo lds. In term s of value of assets most important items were two wheelers, television, cycles and four wheelers. The per household average value of all assets was found to be Rs. 4673/- among all respo ndents (Ta ble 22 ). TV was ow ned by a sizeable portion of the respo ndents in all the villages excep ting Pa tikarpali. Deogaon, Bisalpali, Piplipali, Tukirla, Halanda and De ultunda. Ow nersh ip of radio was high in M urum kel, B ardo l, Baulsingha, Chandipali, Tukurla and Nuagudesira.. Ow nership of four wheelers was found only in Katapali and Tukurla. Tape recorder was an important possession in Bardol, H alanda and Nuaguresira. Two wheelers were found relatively more in Gudesira, Turunga, Deogaon and Haldipali. The items found exten sively were bicycle and watch. It is also observ ed that there ex ists variation across the villages in terms of average asset value of the different sample househo lds. Highest asset value w as observed in the villages of Turun ga (Rs.13308/-), Gud esira (Rs.124 48/-) and Nuagudesira (Rs.12123/-). Lowest average asset value was found in the villages of Halanda (Rs.185 6/-), Ambapali (Rs.1750/-) and Patikarpali (Rs.533/-).Given the nature of ow nersh ip pattern of asse ts as outlined above it is relevant to examine the interrelationship between caste and occu pation with ownersh ip of assets from Table 23 and 24. It is important to observe that the SC & ST respo ndents were located in the lowest asset size group of below Rs.10,000/-., while a sizea ble portion of general caste groups (45.9% ) were located in high asset size groups. However, persons belonging to highest asset group (more than 1 lakh) belong ed to OBC category. Facilities and living conditions of sample responden ts: Housing: The facilities available in the houses of sam ple househo lds can be observed from Table 16. Of the total respo ndents abou t 52.5% of the respon dents live in kaccha houses, 19 .25% lived in pucca houses and 28.25% in mixed houses. The houses were found to be electrified in case of 60.0% households. Only 15.0% of the houses had less than 3 room s, while 70.25% of the households did not have their own toilet facility.About 73.0% of the households did not have their own drainage system . Sources of water: Nearly 57.75% of the households depended on Tube well for drinking wa ter (Table 17). About 1.25% depends on their own well. An important source of drinking water has been Village wells. Village wise the dependence on Village wells was high in Baulsingha, Bisalpali, Piplipali and Haldipali. There is piped water supp ly only in the village D eogaon. Only three villages, Tukurla, Halanda and Deultunda reported multiple sources for drink ing w ater. The most important source of water (Table 18) for washing and b athing was river (54%), village pond (25.5%) and m ultiple sources (20.25 %). V illages w ith multiple water sources w ere Tu kurla, H alanda and Deultunda. Source of fuel: The m ost important source of fuel for cooking was firewood (36.5%), electric heater (12.25%) while the bulk of the households used mu ltiple sources (51.0% ). Use of firewood was extensive in the villages of Murumk el, Baulsinga, Bisalpali, Piplipali, Tukurla, Halanda and Deultunda. Similarly, use of electric heater was very high in G hupali, Gudesira and K atapali (Table 19 ). Food intake: The food intake of the sample resp ondents were recorded for breakfast, lunch, evening tiffin/snacks 102 Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci., 1(3): 93-110, 2009 Tab le 16 : Fac ilities an d livin g co nditio ns o f sam ple re spo nde nts Village Kaccha Pucca Mixed Total Electr-ified Gh upa li 50 10 40 100 100 Kh aliap ali 55 10 35 100 40 Patik arpa li 100 100 Murum kel 100 100 80 Gu desira 15 45 40 100 100 Am bap ali 65 35 100 90 Turunga 10 65 25 100 90 Deogaon 25 45 30 100 75 Bardol 60 40 100 100 Pad han pali 5 20 75 100 95 Ka tapa li 35 60 5 100 100 Baulsimgha 75 25 100 Bisa lpali 75 25 100 25 Piplip ali 90 10 100 30 Ha ldipa li 45 15 40 100 80 Ch and ipali 25 10 65 100 70 Tu kur la 85 15 100 Halanda 95 5 100 5 Deultunda 80 20 100 20 Nu agud esira 20 40 40 100 100 Total 52 .5 19 .3 28 .3 100 60 <3 10 50 50 20 10 15 5 10 35 5 35 10 10 20 15 15 3-5 90 50 50 80 65 85 15 65 30 65 55 95 65 90 75 45 90 80 85 55 66 .5 >5 25 85 35 65 25 10 25 55 45 18 .5 Total 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 Ow n toilet Facility 10 50 75 65 100 20 65 5 10 85 10 100 29 .8 Wastage drainage 10 50 25 85 100 70 100 100 27 Table 17: Sources of water for drinking Village Source of water for drinking ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Pu blic su pply Ow n w ell Villa ge w ell Village pond River Tu be w ell Multi source Total Gh upa li 100 100 Kh aliap ali 100 100 Patik arpa li 100 100 Murum kel 100 Gu desira 100 100 Am bap ali 100 100 Turunga 25 10 60 5 100 Deogaon 100 100 Bardol 100 100 Pad han pali 95 5 100 Ka tapa li 100 100 Baulsimgha 100 100 Bisa lpali 100 100 Piplip ali 100 100 Ha ldipa li 100 100 Ch and ipali 100 100 Tu kur la 100 100 Halanda 100 100 Deultunda 100 100 Nu agud esira 100 100 Total 5 1.25 20 .5 57.75 15 .5 100 Table 18: Sources of Water for Bathing Village Source of water for Bathing -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Pu blic su pply Ow n w ell Villa ge w ell Village pond River Tu be w ell Multi source Total Gh upa li 100 100 Kh aliap ali 100 100 Patik arpa li 15 80 5 100 Murum kel 100 100 Gu desira 90 10 100 Am bap ali 100 100 Turunga 80 20 100 Deogaon 100 100 Bardol 100 100 Pad han pali 100 100 Ka tapa li 100 100 Baulsimgha 100 100 Bisa lpali 95 5 100 Piplip ali 100 100 Ha ldipa li 100 100 Ch and ipali 95 5 100 Tu kur la 100 100 Halanda 100 100 Deultunda 100 100 Nu agud esira 35 65 100 Total 25 .5 54 0.25 20.25 100 103 Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci., 1(3): 93-110, 2009 Table 19: Source of fuel for Cooking Village Fire wood Gh upa li Kh aliap ali 35 Patik arpa li Murum kel 100 Gu desira Am bap ali 5 Turunga Deogaon Bardol Pad han pali Ka tapa li Baulsimgha 95 Bisa lpali 100 Piplip ali 100 Ha ldipa li Ch and ipali Tu kur la 100 Halanda 95 Deultunda 100 Nu agud esira Total 36 .5 Cow dung 5 0.25 Coal - Heater 50 90 15 10 5 10 60 5 12.25 Similarly, occupation wise one observes that while persons in most occupations were mainly located in the low asset size group of be low Rs.10,000/-, relatively higher num ber of p erson s located in high asset size groups belon ged to service class and other occup ation groups. Gas - Kerosene - M ultiple 50 65 100 10 80 90 95 100 90 40 5 95 100 5 95 51 Total 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 was Rs.1395/- only. Village wise also one observes variations. Villages w ith relatively high er per house hold income were Gudesira, Turunga, Bardol, Pa dhanpali, Katapali, Haldiplai, Chandipali, and Nuaguresira. Villages with highest per capita monthly income were Gudesira, Turunga, Padhanpali, Haldipali, Chandipali and Nuaguresira. The interrelationship between caste and occupation with income pattern can be examined from Table 25 and 26. The lowest per household monthly income was by SC & ST and highest by general caste followed by OBC. Occupation wise it is found that highest per househo ld mon thly income was recorded by service class followed by household industry and cultivation and the lowest income was found in case of wage-earners, artisans and persons dependent on forestry. Source of income: It is observed that 48.75% of the households reported earning incom e from agriculture followed by slightly higher proportion (54.75%) earning income through wage labour. While 12.25% reported earning income through service, 8.75% earned income through shop /business. A bout 51% of the respon dents revealed earning inc ome throug h othe r sources. It is however interesting to no tice that about 51.36% of the total income earned was contributed by agriculture followed by 19.56% by wage-earners, 12.71% by service and only 4 .71% by bu siness and trade. Other sources of income contributed nearly 11.67% of the total income. This indicates that a large segment of the population was engaged in cultivation and wage labour, and this occupation was the primary source of living for the people in the region. V illage-wise also one notices some variations. Cultivation w as relatively more impo rtant in Murum kel, Gudesira, Padhanpali and Chandipali. Wage labour was an im portan t source of income in Khaliapali, Am bapali, Bisalpali, Piplipali and Deultunda, where as service is an importan t source in Tu runga, Bardol, Padhanpali and Haldipali. Simialrly Business was an impo rtant source in Ambapali, Deultunda and Nuaguresira. Other occupations w ere relatively more impo rtant in Patikarpali, Piplipali and H aldipali. The level of income of the sample respondents was found to be very low as can be seen from the per househo ld income as well as the per capita income of the sample households. The per-household monthly income stands at Rs. 5136/-, while the per capita monthly income Hea lth and Nutrition Status: The health status of peo ple of the different villages (Table 27) reveals the common ailments to be cough & cold and headache amon g the villagers.. People of four villages (all 100%) reported that they are not suffering from any common alim ents frequently.. Out of the 20 villages, cent percent househo ld of 13 villages reported that they are treated by the do ctors whenever they suffer from any h ealth problem. T hey visit hosp itals to seek help from the doc tors. The common chronic diseases in terms of air borne diseases were Tuberculosis, respiratory infections, Pox, asthma and others. The water borne diseases were dysentery, diarrhea, jaundice and other diseases and parasitic infections. Incidences of such chronic diseases were reportedly much less among the sam ple households. Nutritional Status: A total of 1473 person belon ging to different age and sex groups in twenty villages were the sample respondents for the assessment of nutritional status (Table 29 ). 104 Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci., 1(3): 93-110, 2009 Table 20a: Food intake pattern of sample households Village Breakfast -------------------------------------------------------------------------Mud hi & tea Rice/ Pakahal Other No Total Lunch --------------------------------------------------------------------------------Rice, Onion Rice, Dal Ric e, D al, Ri ce, d al, Total /Sag / Curry Cu rry Curry, N.Veg Gh upa li Kh aliap ali Patik arpa li Murum kel Gu desira Am bap ali Turunga Deogaon Bardol Pad han pali Ka tapa li Baulsimgha Bisa lpali Piplip ali Ha ldipa li Ch and ipali Tu kur la Halanda Deultunda Nu agud esira 90 100 85 30 60 80 15 5 70 70 20 100 30 5 30 100 10 10 40 20 100 75 100 100 95 100 56 10 5 60 20 85 95 10 30 5 70 5 - 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 25 10 - 15 59 80 30 35 55 90 75 90 25 90 90 100 - 85 5 20 70 100 65 100 100 100 90 40 10 10 75 100 95 10 51 10 5 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 00 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 Total 39 .5 37.75 22 .8 - 100 1.75 39 57.75 1.5 100 Table 20b: Food intake pattern of sample households Village Evening ---------------------------------------------------------------------------Muri &tea Rice/ Pakahal Other No Total Dinner ---------------------------------------------------------------------------Rice, Onion/ Rice, Dal Ri ce, D al, Ri ce, d al, Total Sag / Curry Cu rry Curry N.Veg Gh upa li Kh aliap ali Patik arpa li Murum kel Gu desira Am bap ali Turunga Deogaon Bardol Pad han pali Ka tapa li Baulsimgha Bisa lpali Piplip ali Ha ldipa li Ch and ipali Tu kur la Halanda Deultunda Nu agud esira 5 5 20 30 10 55 50 20 45 60 30 58 100 45 10 54 95 5 5 20 5 50 5 - 45 15 20 10 5 - 95 95 100 80 70 90 45 75 100 40 70 100 90 50 5 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 30 59 - 55 59 85 55 15 65 59 95 60 100 70 100 5 100 100 35 45 5 15 35 85 35 5 5 100 100 40 100 100 65 10 - 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 Total 29 .5 10 .5 4.75 55 .3 100 1.75 52 45.75 0.5 100 Tab le 21 : As set ow ners hip p ositio n of sam ple re spo nde nts Item No. of Hhs % H hs < 5 years, 5-16 years and >16 years of age weree calculated. The consolidated list of villages showing proportion of population in different age–group having normal nutritional status has been p resented in Tables 3032. W hen scores were assigned on per cent of normal population at each age -group in eac h village (Table 30), Patikarpali, Chandipali Halanda and Deultunda scored more than 80% , Gudesira, Turunga, Baulsimgha, Haldipali, Nuagudesira scored between 60-80% and rest <60%. The villages like Bisalpali, Tukurla Ghupali, Khaliapali, Murumkel, Ambapali, Deogaon, B ardol, Padhanpali, Katapali, Piplipali requires imm ediate %share in total value Television Ra dio Tape recorder Four wheeler Cycles Two w heeler Tractor Watch/clock 200 193 83 2 290 42 289 50 .0 48.25 20.75 0.5 72 .5 10 .5 72.25 20.39 2.83 2.33 14.61 17.57 38.96 3.30 Total 400 10 0.0 100 Village-wise malnutrition status in terms of weight for age and Body Mass Index of the sa mple belon ging to 105 Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci., 1(3): 93-110, 2009 Tab le 22 : Average asset value of sample households in different villages Village Averag e Asset V alue(Rupee s) Gh upa li 4059 Kh aliap ali 2016 Patik arpa li 533 Murum kel 2266 Gu desira 12448 Am bap ali 1750 Turunga 13308 Deogaon 6460 Bardol 5370 Pad han pali 3338 Ka tapa li 3983 Baulsimgha 2492 Bisa lpali 2342 Piplip ali 2036 Ha ldipa li 9268 Ch and ipali 3586 Tu kur la 2033 Halanda 1856 Deultunda 2190 Nu agud esira 12123 Total 4673 Tab le 25 : Ho use hold monthly income (Rs) of caste groups of sa mp le households Ca ste Total SC ST OBC GEN Total 2592 4262 5961 11538 5136 Tab le 26 : Ho use hold mo nthly incom e (R s.) of o ccu pati on groups of sample households Occupation Total Cultivation Agril labour Non-agril. Lab Service. Business Forest Artisan HH -industry Othe rs 6712 2843 2234 10715 5403 1242 2855 8083 5363 Total 5136 Table 23: Assets owned by different caste groups Ca ste <10000 SC ST OBC GEN 135 (95.7) 31 (93.9) 165 (87.3) 17 (45.9) 10000-30000 5 (3.55) 2 (6.06) 18 (9.52) 13 (35.1) 30000-50000 1 (0.71) 0.00 3 (1.59) 5 (13.5) 50000-1 lakh 0.00 0.00 1 (0.53) 2 (8.11) >1 lakh 0.00 0.00 2 (1.06) 0.00 Total 141 33 189 37 Total 348 (87.0) 38 (9.50) 9 (2.25) 3 (0.75) 2 (0.50) 400 Table 24: Assets owned by different occupation groups Occupation <10000 > 1 lakh Total Cu lt Agril. Lab Non-ag. La Service Business Forest Artisans HH ind. Othe rs 123 (80.39) 24 (96) 73 (98.65) 30 (69.77) 6 (100) 38 (100) 29 (93.55) 2 (100) 23 (82.14) 10000-30000 24 (15.7) 1 (4) 1 (1.35) 9 (20.93) 0 0 0 0 3 (10.71) 30000-50000 5 (3.3) 0 0 3 (6.98) 0 0 0 0 1 (3.57) 0.00 0 0 0.00 0 0 2 (6.45) 0 1 (3.57) 1 (0.65) 0 0 1 (2.33) 0 0 0 0 0 153 25 74 43 6 38 31 2 28 Total 348 (87.0) 38 (9.50) 9 (2.25) 3 (0.75) 2 (0.50) 400 Table 27: Common ailments of sample households Co ugh & c old Headache 50000-1 lakh Table 28: Treating physician and place of treatment No Doctor No respo nse Gh upa li Kh aliap ali Patik arpa li Murum kel Gu desira Am bap ali Turunga Deogaon Bardol Pad han pali Ka tapa li Baulsimgha Bisa lpali Piplip ali Ha ldipa li Ch and ipali Tu kur la Halanda Deultunda Nu agud esira 100 100 100 100 98 .9 100 97 .6 85 .7 100 100 100 100 87 .8 87 .3 98 .6 82 .3 - 2.4 1.2 1.4 - 0.1 100 13 .1 10 .8 12 .7 17 .7 100 100 100 Gh upa li Kh aliap ali Patik arpa li Murum kel Gu desira Am bap ali Turunga Deogaon Bardol Pad han pali Ka tapa li Baulsimgha Bisa lpali Piplip ali Ha ldipa li Ch and ipali Tu kur la Halanda Deultunda Nu agud esira 100 100 100 100 98 .9 100 100 91 .7 100 100 100 100 100 97 .2 82 .9 3.2 92 .5 100 76 .5 1.1 100 8.3 2.8 17 .1 96 .8 7.59 23 .5 100 100 100 100 98 .9 100 100 92 .9 100 100 100 100 100 97 .2 94 .3 82 .3 8.5 100 100 1.1 100 7.1 2.8 5.7 17 .7 1.5 - Total 78 .8 0.8 20 .4 Total 88 .3 11 .7 93 .6 6.4 106 Hospital No respo nse Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci., 1(3): 93-110, 2009 Table 29: Age-Group w ise sample distribution in the study area Sam ple fa mily Age Group M ale Fem ale Total mem bers in years 0-5 39 33 72 >5-16 127 90 217 >16 691 493 1184 Grand Total 856 617 1473 intervention to meet their nu tritional requirements through awareness campaign and training. Prevalence of higher proportion of normal children in almost all villages might be attributed to longer duration of breast feeding in the locality. Table 31 presents the level of malnutrition among the various age-g roups. In all the age groups, proportion of females with malnutrition has been more than the males. The percentage of females with normal nutritional status were 9, 14 and 76.3 % in 0-5, >5-16 and >16 years category respectively in comparison to 20.5, 29.9 and 76.3% in male categ ory. Table 32 reve als that around 21% from male child category (0-<5 yrs) and 30% from age-group of >5-16 yrs were normal in nutritional status. The percentage of norm al female children were still less, i.e only 9% and 14 % respectively. The children suffering from severe malnutrition was 25% in the age-group of >516 years where as it was 9.7% in 0-<5 yrs age-group. Less proportion of children belonging to malnourished group (Fig. 2) may be due to prolonged breast-feeding practices prevalent in the area. Fig. 1 and 2 reveal that a slightly higher proportion of the population belonging to age – group 5-16 years showed poor nutritional status (sev ere malnutrition ) in comparison to <5 years as well as >16 years. This perhaps indicates that this section of people was not able to meet the nutritional needs as per the requirement for the grow ing pe riod. In Orissa more than half (54%) of the children under three years are undernourished (IIPS 2001) and the proportion of children who are severely malnourished stand at 18-21%. In the present observation the percentage of severely malnourished was observed to be higher in the age group of 5-1 6 in both th e sex group (Fig. 3). When mean height of Boys and girls within the age group of 16 Tab le 30 : Co nso lidated list of v illage- wis e distrib ution of N orm al (N on- maln our ished ) sam ple SN Name of the Village 0-5 yrs >5-1 6 yrs >16 yrs -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Total no No rma l % Total no No rma l % Total no No rma l % of samples of samples of samples 1 Gh upa li 7 0 23 76 2 Kh aliap ali 4 0 25 28 62 82 3 Patik arpa li 1 100 3 100 49 92 4 Murum kel 9 22 10 0 57 84 5 Gu desira 4 50 19 26 65 92 6 Am bap ali 1 0 10 50 48 77 7 Turunga 5 60 64 77 8 Deogaon 5 0 20 20 59 97 9 Bardol 7 14 21 10 56 95 10 Pad han pali 6 17 21 14 45 82 11 Ka tapa li 5 0 10 30 70 89 12 Baulsimgha 2 50 6 17 80 98 13 Bisa lpali 6 0 10 0 62 90 14 Piplip ali 6 0 7 14 61 90 15 Ha ldipa li 5 20 15 20 51 92 16 Ch and ipali 7 43 63 94 17 Tu kur la 8 0 4 0 50 86 18 Halanda 5 60 62 81 19 Deultunda 2 100 62 77 20 Nu agud esira 3 67 10 40 55 73 Tab le 31: M alnutrition statu s based on n utritional anth ropo metry Age-G roup(years) Weight for Age -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Normal M ild M ode rate Seve re Total 0-5 M ale 8 12 14 5 39 Fem ale 3 13 15 2 33 Total 11 25 29 7 72 >5-16 M ale 38 27 30 32 127 Fem ale 13 31 23 23 90 Total 51 58 53 55 217 Body M ass Index -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------->16 M ale 647 34 2 8 691 Fem ale 376 84 21 12 493 Total 1023 118 23 20 1184 107 % N ormal Avg Score out of 1 0.4 0.47 1.0 0.47 0.67 0.47 0.7 0.47 0.47 0.47 0.47 0.6 0.33 0.4 0.6 0.8 0.33 0.8 0.9 0.66 % Seve re 20 .5 9.1 15 .3 12 .8 6.1 9.7 29 .9 14 .4 23 .5 25 .2 25 .6 25 .3 93 .6 76 .3 86 .4 1.2 2.4 1.7 Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci., 1(3): 93-110, 2009 Fig. 5: Mean height of girls in comparison with standards Fig. 1: Prevalence of different level of malnutrition in children Fig. 2: Percent distribution of normal persons in different age groups Fig. 6: Mean weight of girls in comparison with standards Fig. 3: Prevalence of sever malnutrition in different age groups Fig. 7: Mean weight of girls in comparison with standards Table 32: Proportion of sam ple with normal and severe malnourishment Normal Severe malnourished 0-5 yrs Male 20.5 12.8 Fem ale 9.1 6.1 Average 15.3 9.7 >5-16 yrs Male 29.9 25.2 Fem ale 14.4 25.6 Average 23.5 25.3 >5-16 yrs Male 93.6 1.2 Fem ale 76.32.4 Average 86.4 1.7 Fig. 4: Mean height of boys in comparison with standards years were compared with N CH S standard as well as w ith “W ell to do Indians”, there is a gap in the trend in all the age groups for the present population (Fig. 4, 5) and the gap is relatively wider in weight for age with minor deviations (Fig. 6, 7). This indicates that both in terms of height and w eight in relation to age, the sam ple population does not come near the NCH S standard nor the “W ell to do Indians”. Therefore , it may be desirable for an early intervention, particularly for the ag e group o f 0-5 and 5-16 years to make them aware of the nutritional requirement for their growth. Quality of life index: On the basis of the value function stated in the methodology section the QOL (Quality of Life Index) of different households were computed for the different villages which are presented the Table 33 . It is 108 Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci., 1(3): 93-110, 2009 Table 33: Village-wise Quality of Life Index Villages Index Gh upa li 4.03 Kh aliap ali 3.69 Patik arpa li 3.39 Murum kel 3.54 Gu desira 5.22 Am bap ali 4.59 Turunga 5.15 Deogaon 5.56 Bardol 5.93 Pad han pali 4.36 Ka tapa li 5.61 Baulsimgha 3.17 Bisa lpali 2.67 Piplip ali 2.89 Ha ldipa li 4.24 Ch and ipali 5.65 Tu kur la 2.93 Halanda 2.98 Deultunda 3.10 Nu agud esira 5.11 Total 4.19 Status Average Average Average Average Fair Average Fair Fair Fair Average Fair Average Poor Poor Average Fair Poor Poor Average Fair Average Table 34: Caste-wise Quality of life index Ca ste Index SC 3.40 ST 3.65 OBC 4.63 G E N E RA L 5.43 Total 4.19 Status Average Average Average Fair Average Table 35: Occupation-wise Quality of life index Ca ste Index Cultivation 4.68 Agril. Labour 3.95 Non-Agril Labour 3.30 Service 5.38 Business 5.18 Forest 2.98 Artisans 3.62 Hh Indu stry 5.16 Othe rs 4.25 Total 4.19 Status Average Average Average Fair Fair Poor Average Fair Average Average CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION Although the Bargarh cement works has made some contribution over the years to community development particularly in the areas of education and sports ,health care ,infrastructure ,water and sanitation for which a major proportion of the population had an “average” quality of life(not poor) ,there are villages with poor QOL which may be given priority providing infrastructure, water, saniation, healthcare, education etc. as a part of Corporate Social Responsibility. One of the concerned area in the locality is rise in unemployment and a shift from agriculture profession to other areas. The BCW may consider providing vocational training on indigenous knowledge and rural technology to the underprivileged com mun ity by way of opening Vocational training Centres in the locality. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Financial support by Ib Thermal Power Station in the form of a research project to the senior author (PCM) is gratefully acknowledged. REFERENCES CSE, 2005. Co ncrete Facts: The life Cycle of the Indian cement Industry. Centre for Science and Environment Publiction. New Delhi, pp: 163. Day, H. and S.G. Jankey, 1996 . Lessons from the literature: Towards a holistic model of Quality of Life. Background paper for the World Bank’s Annual development Report, 2000. PDF Archives, The Beijer Institute of Ecolog ical Econo mics, Beijer. Echevarria-U sher, C., 1999. Mining and Indigenous Peoples: Contributions to an intercultural and Ecosystem understanding of health and wellbeing. Paper presented at the Ecosystem Health Congress, Sacramento. Forget, G. and J. Lebel, 2001.An Ecosystem approach to Human Health. Int. J. Occup . Environ. H ealth,7 (Supp 2): S3-S36. Kumar , P., 1996. Socioeconomic profile of W est Bokaro Mining Comp lex . M.Tech. Thesis, Indian School of Mines, D hanbad, pp: 86. Mishra, P.C., B.K. Mishra and P.K. Tripathy, 2008. Socio-eco nom ic profile and quality of life index of sample households of mining area s in Talcher an d Ib Valley coal mines in Orissa. J. Hu man E col., 23(1): 13-20. Mishra, P.C., B.K. Mishra, P.K. Tripathy and K . Meh er. 2009. Industrialisation and sustainable Development: A case study on socio-ecological profile, health, nutrition status and quality of life of people around Ib thermal power station of Jharsuguda, Orissa. The Ecoscan. 3(1-2): 119-132. observed that for the over all sample households the quality of index stands at 4.19, which is considered to be Average in the value function. Village- wise it is noticed that the villages with slightly improved position we re Gudesira, Turunga, Deogaon, Bardol, Katapali, Chandipali and N uagudesira, where the status is considered “Fair”. On the other hand villages which witness lowest quality of life and recorde d as “Poo r” were Bisalpali, Piplipali, Tukurla and Halanda. Rest of the 9 villages are considered having “Average” quality of life. Highest quality index was registered by genera l caste (Table 34) followed by OBC and the lowest inde x is noted for SC followed by ST. However only g enera l caste recorded a “fair” quality of life compared to all other groups identified as having “Average” quality of life. Occupation wise (Table 35) it is noticed that highest index was registered by service class followed by business and household industry (with a “fair” quality of life) and the lowest was noted in case of persons dependent on forestry (with a “poor” quality of life) followed by no n- agricultural labour, artisans and agricultural labour, with “Average” quality of life. Cultivators were foun d to be havin g a “A verag e” qu ality of life as w ell. 109 Curr. Res. J. Soc. Sci., 1(3): 93-110, 2009 Noronha, L. and S. Nairy, 2005. Assessing quality of Life in a mining region. Economic and Political W eekly, XL(1): 72-78. Park, J.E. and J. Park, 1991. Preventive and Social Medicine.13th Edn., Banarasi Bharat Publication Jabalpur, India. Prusti, B.K., 1996. An investigation in to the Socioecon omic profile of Bhow ra Area of Jharia Coalfields. M.Tech . Thesis, Indian School of Mines, Dhanbad, pp : 96. Saxena, N.C., A.K. Pal, B.K. Prusty and P. Kumar, 1998. Quality of Life Index of the Mining area. In: Special issue on Environme nt of the Indian Mining and Engineering Journal, Ce ntre of M ining E nvironme nt, Indian School of M ines, D hanbad, July :15 -18. Sheykhi , M.T., 2006. General review of the sociological challenges and prospects of population in Iran-A sociological study of qua lity of life. J. Social Sci.,12(1):21-32. Singh, O.P.,1989. Environmental Developm ent: A Case of Life Quality in the Graet Metropolies of India. In: Dimensions of Development Planning. Pandey, D.C. and P.C.Tiwari (Eds.). Criterion Publication. New Delhi. pp: 133-144. Singh, O.P., 1999. Defining and Determining the Quality of Life: A Case of Towns of the U.P. Himalaya, India. In: En vironmental Development and Manag eme nt. Pandey, G.C. and D.C. Pandey (Eds.).Anmol Publ.New Delhi, pp: 347-352. 110