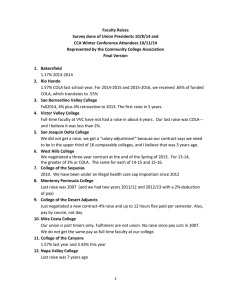

This publication was made possible by a grant from:

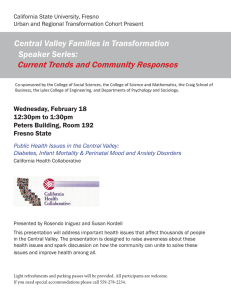

advertisement